Abstract

A 58-year-old man with 10 year history of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) presented with a bulging mass (3.2×1.6×1.5 cm) in the right anterior abdominal wall. On microscopic examination the mass was found to be an epithelial neoplasm in the background of lymphoid proliferation. The epithelial cells were of moderate size, with scant cytoplasm and round nuclei, forming glandular, alveolar or sheet-like structures. These cells were immunoreactive for cytokeratin 20, chromogranin and synaptophysin. The above findings supported a diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). The background small lymphocytes expressed phenotypic markers of B cells (CD20) and CD5, consistent with his known diagnosis of CLL. The incidence of a patient with a known history of CLL who develops a secondary MCC is rare. This is believed to be the second case report of a single lesion containing CLL and MCC.

BACKGROUND

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is a clonal proliferation of small B lymphocytes associated with humoral and cellular immune dysfunction. It is common, usually indolent, and occurs primarily in middle-aged and elderly individuals, with increasing frequency in successive decades of life. The initial course of CLL is relatively benign but is usually followed by haematological complications or by a terminal, progressive and resistant phase with increased incidence of second neoplasm including squamous cell carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma, melanoma and Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).1

MCC is a rare cutaneous neoplasm of neuroendocrine origin with an unknown aetiology. It mostly occurs as an asymptomatic, solitary, firm and red-pink nodule involving the head and neck region. It has been linked to increased sun exposure,2 in its anatomical and in its geographical distribution. The tumour has been reported to occur in association with immunosuppression related to haematological malignancies, AIDS or organ transplant.3 There have been only 10 case reports of MCC arising in patients with CLL in English literature.4,5 Barroeta and Farkas recently reported a case of MCC and CLL of the arm, diagnosed on fine-needle aspiration biopsy.11 We present an additional case of MCC in a patient with CLL, with concurrent involvement of MCC and CLL in a single anatomical location diagnosed on a surgically excised specimen.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 58-year-old man with a past medical history of CLL did well for 10 years after initial diagnosis without therapeutic intervention. He subsequently developed progressive disease including splenic involvement and general adenopathy on CT scan. He then developed a bulging skin mass (3.2×1.6×1.5 cm) along the right lower quadrant of (anterolateral lower) abdomen upon recovering from a bout of shingles. The skin lesion was resected. In addition, the patient developed right groin adenopathy shortly after the initial surgery. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging demonstrated intense hypermetabolism within the enlarged right inguinal lymph nodes, consistent with tumour involvement. There was much less intensity of PET imaging seen at other sites relative to marked adenopathy on CT scan, and this was likely reflective of CLL. The right groin biopsy of the lymphadenopathy was done.

INVESTIGATIONS

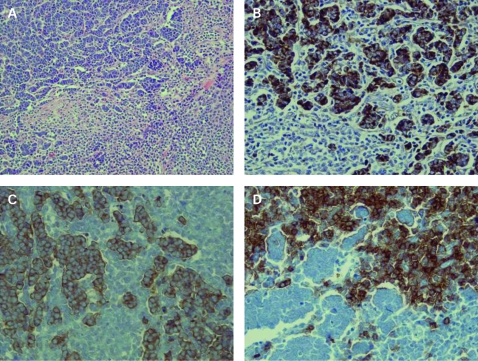

Abdominal skin excisional specimen showed an epithelial neoplasm with lymphoid cell proliferation in the background. The tumour was centred in the dermis, extended into the subcutaneous tissue and had no direct connection to the overlying epidermis (fig 1A). The epithelial cells grew in glandular, alveolar or sheet-like pattern. These cells were of moderate size, round and blue. These cells had scant cytoplasm and round nuclei with evenly dispersed chromatin giving them a characteristic “smoky” appearance. Nucleoli were not prominent. Mitotic activity was very high. Immunohistochemical stains revealed that the neoplastic epithelial cells were positive for cytokeratin 20 (fig 1B), chromogranin and synaptophysin, and this supported a diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma. The diffusely infiltrating lymphocytes were monomorphic, small and atypical lymphocytes with high nuclear cytoplasmic ratio. The nuclei of the lymphocytes were round and had clumped chromatin pattern. Immunohistochemical stains revealed that these atypical small lymphoid cells stained positive for CD20 (fig 1D) and CD5 (fig 1C). The morphology, and immunophenotype with prior history of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, confirmed the diagnosis of CLL involving the lesion.

Figure 1.

(A) The cutaneous mass showing epithelial neoplastic cells with lymphomatous proliferation in the background (H&E, ×200). (B) The epithelial neoplastic cells are positive for cytokeratin 20 (immunoperoxidase, ×400). (C, D) The background proliferating lymphohcytes are positive for CD5 (C) and CD20 (D) (immunoperoxidase, ×400).

The right groin lymph node biopsy also revealed both neoplasms, morphologically similar to the lesion from the abdominal wall; this supports the diagnosis of metastatic MCC to a lymph node involved by CLL.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient passed away 3 years after the diagnosis of MCC along with pre-existing CLL.

DISCUSSION

CLL is generally a disease of the older people. Most patients will ultimately develop bone marrow and peripheral blood infiltration. Moreover, generalised lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly are not uncommon clinical manifestations. Furthermore, advanced stages of the disease are typically characterised by hypogammaglobulinaemia and autoimmune phenomenon, often resulting in infectious complications, haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia. Like most indolent lymphomas, CLL is not considered to be curable with currently available therapy. However, treatment with alkylating agents, prednisone and, more recently, purine analogues and rituximab has been found to be remarkably effective in producing long-term remissions. The extent of the disease at the time of diagnosis and mutational status of variable region of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (IgVH) are the best predictor of survival.

CLL is associated with an increased risk of developing common skin cancers. Potentially, this risk may include the rarer skin cancer such as MCC, which has a much poorer prognosis and therefore, if recognised, should be treated aggressively. Manusow et al6 showed that in CLL, overall risk of developing a second primary tumour is threefold, and risk increased eightfold when second primary tumours of skin tumours were considered.

We already know that MCC is a rare and aggressive neuroectodermal tumour formed of cells with membrane-bound neurosecretory granules frequently in the elderly patients.7 MCC is commonly found on sun-exposed areas and an increased incidence of MCC was recently reported in patients who had received UVA photochemotherapy.8 Immunosuppression is one of classic risk factors for development of MCC. It has been reported that MCC developed in immunocompromised patients (CLL, transplant recipients).3 The prolonged history of CLL and chemotherapy is prone to cause immunosuppression, which may account for the increased risk of developing skin cancers including MCC.

All of the above factors can help to explain the reason why the patients who have a CLL have an increased risk of developing a second primary malignancy including MCC. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the second report of a collision tumour in a single lesion containing MCC and CLL, and the first documented case of such collision tumours diagnosed on a surgically excised specimen. The diagnosis was not difficult after the careful histological examination and immunohistochemistry studies.

MCC is an aggressive tumour with 12–45% being lymph node positive at presentation. This increases to 55–79% during the course of the disease. The 5 year survival has been reported at 30–64%.9 Due to a much poorer prognosis of MCC than CLL, when recognised, the disease should be treated aggressively. It is recommended to evaluate the sentinel lymph node of this cutaneous lesion followed by further node dissection or adjuvant therapy if necessary.10 The treatment for our patient involved wide local excision with external beam radiotherapy of total 4500 cGy followed by fludarabine and rituximab for CLL.

LEARNING POINTS

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is known to predispose to second neoplasm including squamous cell carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma and melanoma.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) occurring in patients with pre-existing CLL is very rare.

This case is unique since both lesions (MCC and CLL) were present in a single anatomical site (collision tumour).

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levi F, Randimbison L, Te VC, et al. Non Hodgkin’s lymphomas, chronic lymphocytic leukemias and skin cancers. Br J Cancer 1996; 74: 1847–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller RW, Rabkin CS. Merkel cell carcinoma and melanoma: etiological similarities and differences. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1999; 8: 153–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008. March; 58: 375–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robak E, Biernat W, Krykowski E, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma in a patient with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with cladribine and rituximab. Leuk Lymphoma 2005. June; 46: 909–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papageorgiou KI, Kaniorou-Larai MG. A case repot of Merkel cell carcinoma on chronic lymphocytic leukemia: differential diagnosis of coexisting lymphadenopathy and indications for early aggressive treatment. BMC Cancer 2005; 5: 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manusow D, Weinerman BH. Subsequent neoplasia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. JAMA 1975; 232: 267–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol 1972; 105: 107–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warner TF, Uno H, Hafez GR, et al. Merkel cells and Merkel cell tumours: ultrastructure, immunocytochemistry and review of the literature. Cancer 1983; 52: 238–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howard RA, Dores GM, Curtis RE, et al. Merkel Cell carcinoma and multiple primary cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006; 15: 1545–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 2300–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barroeta JE, Farkas T. Merkel cell carcinoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (collision tumor) of the arm: a diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Diagn Cytopathol 2007; 35: 293–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]