Abstract

A young man from Jamaica was admitted with cachexia, postprandial epigastric pain and vomiting. His abdominal examination revealed a soft abdomen with hyperactive bowel sounds, the laboratory investigations showed mild anaemia and hypoalbuminaemia, and abdominal x ray showed dilated and oedematous bowel loops. A duodenal biopsy revealed larvae and eggs in the epithelium consisted with Strongyloides infection. In retrospect the patient was found to be HTLV-1 positive. Helminthic infections can present with bowel obstruction even in the absence of eosinophilia or diarrhoea, and should be considered in patients with the appropriate epidemiological background.

BACKGROUND

At times of migration and ethnically diverse communities there is a greater need for proficient diagnostic skills as medical doctors encounter various diseases, often infectious, which were not previously common in Western countries, especially Europe.1 It is therefore extremely important to consider the epidemiology when investigating individual cases. The following case report describes a patient who presented with variable manifestations; however, the underlying cause of his illness was a surprise.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 38-year-old man was admitted with postprandial epigastric pain, anorexia and weight loss. He was Jamaican and had been working in the construction industry in the UK for the last 15 years. He reported having this pain for the last 4 months, worsening during the last 3 weeks. In addition to pain, his meals were followed by bloating and occasionally he would vomit undigested food. His oral intake became poor and his bowel habit was reduced in frequency and amount. The patient reported having lost 25 kg in the last 3 months. His past medical history showed he had a barium meal in 2003 which revealed signs of chronic duodenitis, but no active ulcer was present. Otherwise he was fit and well. His medications were lansoprazole and Gaviscon which provided him with some relief. The patient did not smoke or use alcohol.

On examination he appeared malnourished. His abdomen was distended and tympanic and the bowel sounds were increased in frequency.

Laboratory investigations revealed haemoglobin (Hb) 10.1 g/dl, white cell count (WCC) 12.0, platelets (PLT) 603 000/μl, albumin 22 g/dl and C-reactive protein (CRP) 18. The abdominal radiograph is shown in fig 1.

Figure 1.

Abdominal x ray revealing dilated, oedematous bowel loops.

The diagnosis of small bowel obstruction was made and conservative management was initiated.

INVESTIGATIONS

The abdominal x ray revealed prominent bowel loops with oedematous walls. A barium follow-through study had poor results as the contrast would not pass to the small bowel. Duodenal dilation was noted but there was no evident stricture.

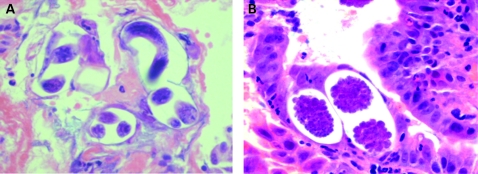

The patient underwent an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Before insertion of the endoscope, 800 ml of bilious fluid was removed from the patient’s stomach by nasogastric tube. During the gastroscopy a dilated stomach and duodenum were noted but no profound cause of obstruction was found. Biopsies of the wall in the D2 region were taken. These revealed eggs and filariform and rhabditiform larvae consistent with Strongyloides stercoralis infection (fig 2). Filariform larvae were found in patient’s faeces along with positive serology. Retrospectively, the patient was found to be HTLV-1 positive (EIA test positive, Western blot used as confirmatory test).

Figure 2.

(A) Histological section of the intestinal mucosa showing an adult worm and larvae. (B) Eggs in the intestinal mucosa.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Based on the symptoms of small bowel obstruction in a young patient accompanied by acute phase response (elevated WCC, PLT and CRP), the differential diagnosis was directed to inflammatory processes such as Crohn’s disease and tuberculous ileitis. The possibility of neoplasia (intestinal lymphoma) was also considered.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient was treated with Ivermectin for 2 weeks and fully recovered. His appetite improved and he gained weight quickly.

DISCUSSION

A young patient with symptoms of bowel obstruction and cachexia was diagnosed with Strongyloides infection. Similar cases have been documented in the literature worldwide, especially in immunocompromised patients.2

Infection with this parasite is usually asymptomatic (intestinal strongyloidiasis), although sometimes it can be much more aggressive (hyperinfection syndrome, disseminated strongyloidiasis) as described above.3

The population of North London is complex with diverse epidemiological backgrounds. Therefore, the differential diagnosis of common presentations needs to be enhanced by more “exotic” diseases.

The young age, the lack of fever or diarrhoea and the lack of eosinophilia did not suggest a parasitic infection.

Eosinophilia exists in 50–80% of asymptomatic patients, but a low eosinophil count is more common in patients with more severe disease;4 in the initial stages of a Th2- IL5 driven infection the peripheral count of eosinophils rises but in later stages eosinophils infiltrate the respective target tissues.5

No history of steroid use was present and the HIV test was negative.

Retrospectively, it was discovered that the patient’s serum was positive for HTLV-1. A link between these two infections is documented in the literature.6 The switch from a Th2 to a Th1 response caused by the HTLV-1 virus leads to enhancement of the Strongyloides autoinfection cycle and the emergence of major dysfunction throughout the host’s body.6,7

The diagnosis of S stercoralis infection is established by the detection of the larvae in biological samples, commonly stools, or by immunological essays. An examination of a single stool sample will detect rhabditiform larvae <30% of the time; however, more specialised techniques can raise the sensitivity to >85%.3

Helminthic infections, especially of the nematodes family, can present with symptoms of bowel obstruction and simple investigations such as microscopy and culture of multiple stool samples can be extremely helpful in establishing the diagnosis, provided helminthic infections have been considered in the differential diagnosis, which should always be guided by the epidemiological data available.8

LEARNING POINTS

Helminthic infections should be considered in patients with bowel obstruction and cachexia, especially when a suitable epidemiological background is present.

Lack of eosinophilia and diarrhoea do not exclude the presence of a parasitic infection.

Repeat stool samples can be extremely helpful in revealing parasitic infections even in the absence of diarrhoea.

The presentation of a usually asymptomatic or mild disease with a severe phenotype should prompt the physician to consider the presence of probable risk factors.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gushulak BD, MacPherson DW. Population mobility and infectious diseases: the diminishing impact of classical infectious diseases and new approaches for the 21st century. Clin Infect Dis 2000; 31: 776–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004; 17: 208–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Concha R, Harrington W, Jr, Rogers AI. Intestinal strongyloidiasis: recognition, management, and determinants of outcome. J Clin Gastroenterol 2005; 39: 203–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genta RM. Global prevalence of strongyloidiasis: critical review with epidemiologic insights into the prevention of disseminated disease. Rev Infect Dis 1989; 11: 755–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutierrez Y. Diagnostic pathology of parasitic infections with clinical correlations. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvalho EM, Da Fonseca Porto A. Epidemiological and clinical interaction between HTLV-1 and Strongyloides stercoralis. Parasite Immunol 2004; 26: 487–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verdonck K, González E, Van Dooren S, et al. Human T-lymphotropic virus 1: recent knowledge about an ancient infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2007; 7: 266–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keystone JS. Can one afford not to screen for parasites in high-risk immigrant populations? Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45: 1310–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]