Abstract

Isolated manifestation of sarcoidosis in the heart is very rare. The present work describes the case of a 41-year-old woman with ventricular tachycardia and severe symptoms of heart failure in June 2006. Clinical, MRI and echocardiographic findings revealed the diagnosis of an arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Due to the severe progression of the disease, cardiac transplantation was performed in August 2007. Histopathological examination of the explanted heart, however, revealed numerous non-necrotising granulomas with giant cells, lymphocytic infiltration and interstitial fibrosis, finally confirming the diagnosis of a myocardial sarcoidosis.

Background

Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic granulomatous disease of unknown cause. It commonly involves the lymph nodes, lung, eyes, kidneys, central venous systems and skin.

Cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis has been reported in 20% to 30% of patients with sarcoidosis at autopsy. However, less than 5% of patients with sarcoidosis have cardiac symptoms, and only 40% to 50% of patients with cardiac sarcoidosis at autopsy were diagnosed as having the condition during life.1 Isolated cardiac sarcoidosis is very rare, with asymptomatic clinical course in the majority of patients.

Cardiac involvement in patients with sarcoidosis has been reported to manifest as complete heart block, papillary muscle dysfunction, congestive heart failure, pericarditis, conduction abnormality, chest pain, sudden death and, in some cases, sarcoid myocarditis can even mimic the symptoms of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. To date, only a few patients have been described with the initial diagnosis of an arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, in which further analysis lead to the final diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis.

Case presentation

In June 2006, a 41-year-old woman presented with ventricular tachycardia and received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). Almost 1 year later, in April 2007, she was admitted to hospital with dyspnoea on exertion and general fatigue. Two-dimensional echocardiography showed a high-grade tricuspid valve insufficiency, a severe right ventricular restriction and a restriction of the left ventricular function (New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II to III). MRI showed an enlarged, hypokinetic and thinned right ventricle and atrium but no fatty infiltration. Clinical, MRI and echocardiographic findings were highly suggestive of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C).

The patient had no family history of ARVD/C or any other notable cardiovascular disorders, and there was no history of inflammatory disease, cough, fevers or recent weight loss. Due to the expeditious progression of the disease, the patient was listed for cardiac transplantation in July 2007, which was performed 1 month later. All pretransplant evaluations (eg, chest x ray and total body CT scan) revealed no pathological findings, and all laboratory parameters were within the normal ranges.

Investigations

The explanted heart was sent to the Department of Pathology for histopathological examination.

Gross examination

Gross examination revealed a heart weighing 313 g and measuring 14.5×11.5×4 cm, showing an enlarged and thinned right ventricle with endocardial fibrosis and extended lipomatous and scarred areas in the left ventricle. The pulmonary valve measured 2 cm and the aortic valve 2.2 cm in cross section dimension, the circumferential length of the tricuspid and mitral valves was 11.5 cm and 8.3 cm, respectively. All coronary arteries were patent and showed only mild arteriosclerotic changes.

Microscopic examination

Samples of the explanted heart were fixed with 4% phosphate buffered formalin, dehydrated and embedded in wax. Sections 2 µm thick were routinely stained with haematoxylin and eosin.

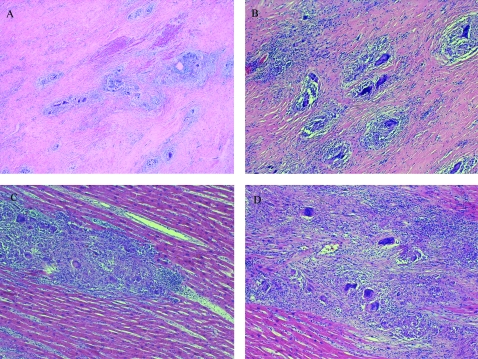

Microscopic examination revealed numerous non-caseating epitheloid granulomas with multinuclear giant cells, surrounding mononuclear infiltration and interstitial fibrosis, affecting the right and left ventricle. There was no fibrofatty replacement of the myocardium.

Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS), Grocott and Ziehl–Neelsen stainings were performed to exclude fungal decay and revealed negative results. Additionally, a polymerase chain reaction for the exclusion of tuberculosis was performed.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for ventricular tachycardia due to ARVD/C includes:

Congenital heart disease

Repaired tetralogy of Fallot

Ebstein anomaly

Uhl anomaly

Atrial septal defect

Partial anomalous venous return

Acquired heart disease

Tricuspid valve disease

Pulmonary hypertension

Right ventricular infarction

Bundle-branch re-entrant tachycardia

Miscellaneous

Pre-excited AV re-entry tachycardia

Idiopathic right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) tachycardia

Histological differential diagnosis of granulomas in the heart includes tuberculosis (contrarily to sarcoidosis characterised by necrotising granulomas) as well as other granulomatous diseases (eg, toxoplasmosis, rheumatic, fungal and idiopathic giant cell myocarditis).

Treatment

After heart transplantation, the patient received anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), ciclosporine A, prednisolone and azathioprine according to local practise. In November 2007, azathioprine was replaced by mycophenolic acid (MPA). The steroid weaning was successful 1 year after heart transplantation. Specific treatment for the sarcoidosis was not initiated.

Outcome and follow-up

After the surprising histological diagnosis of a cardiac sarcoidosis, the patient underwent further investigations (eg, CT scan, continuative laboratory tests, T4/T8 ratio). Finally, an extracardiac affection from sarcoidosis could be excluded. The angiotensin-converting enzyme 1 (ACE1) level, immediately tested after histological diagnosis, was not elevated (23 U/litre; upper limit 55 U/litre).

The post-transplant course was uneventful, the patient is currently NYHA I, routinely obtained endomyocardial biopsies were mostly graded 0 (International Society for Heart & Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) classification).

Only three biopsies, obtained 11 weeks, 4 months and 5 months after cardiac transplantation showed a mild cellular rejection (rejection grade 1). At the 2-year follow-up no non-caseating granulomas have been observed and no cardiovascular or pulmonary disorders were evident. Systolic and diastolic function of the graft were both normal, and no arrhythmic episodes had been documented since the time of cardiac transplantation.

Discussion

To date, 13 patients of both genders, aged 33 to 59, have been described in the English language literature with an initial diagnosis of an arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (table 1), where following histopathological examination the final diagnosis of a cardiac sarcoidosis was made.2–10 Cardiac sarcoidosis was definitively diagnosed due to postmortem examination in three patients, and due to endomyocardial or transbronchial biopsy in nine patients. In one case a 37-year-old man received a heart transplantation, and final diagnosis was confirmed by histopathological examination of explanted heart specimens (fig 1).

Table 1.

Literature review

| Reference | Gender | Age | Symptoms | Manifestation | Diagnosis | Therapy |

| Ladyjanskaia et al10 | M | 44 | Ventricular tachycardia | Heart | Postmortem | ICD implantation |

| Shiraishi et al8 | F | 59 | Complete AV block | Skin, heart, right hilar lymphadenopathy | Endomyocardial biopsy | Corticosteroid therapy pacemaker |

| Vasaiwala et al9 | M | 51 | Ventricular tachycardia | Heart | Endomyocardial biopsy | Not available |

| M | 44 | Ventricular tachycardia | Heart | Endomyocardial biopsy | Not available | |

| M | 44 | Ventricular tachycardia | Heart | Endomyocardial biopsy | Not available | |

| Greif et al3 | M | 37 | Ventricular tachycardia, palpitation, dyspnoea | Heart | Explanted heart | Heart transplantation, corticosteroid therapy |

| Freudevaux et al4 | M | 44 | Syncope | Heart | Endomyocardial biopsy | ICD implantation, corticosteroid therapy |

| Tandri et al5 | F | 46 | Ventricular tachycardia | Heart | Endomyocardial biopsy | Antiarrhythmic therapy |

| Ott et al2 | M | 37 | Cough, sudden shortness of breath, tachycardia | Heart, lung | Transbronchial biopsy | Corticosteroid therapy |

| M | 47 | Ventricular tachycardia | Not available | Postmortem | Cardioversion | |

| M | 33 | Collapse and sudden death | Heart, lung, spleen | Postmortem | No treatment | |

| Hiramatsu et al6 | M | 50 | Ventricular tachycardia | Heart | Endomyocardial biopsy | Antiarrhythmic therapy, corticosteroid therapy |

| Yared et al7 | M | 59 | Exertional dyspnoea, second-degree AV block | Heart, thoracic lymphadenopathy | Endomyocardial biopsy | Corticosteroid therapy |

AV, atrioventricular; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

Figure 1.

A–D. Histological examination of explanted heart specimens revealed several non-necrotising granulomas with giant cells, surrounding lymphocytic infiltration and extensive interstitial fibrosis.

The distinction between arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/ cardiomyopathy and cardiac sarcoidosis is still challenging, as both diseases may occasionally manifest with similar clinical symptoms. The pathogenesis of ARVD/C and sarcoidosis is largely unknown.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/ cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C), predominantly seen in men, is an inheritable cardiomyopathy, usually inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, with variable expressions. The autosomal recessive variant of ARVD/C, named Naxos disease and initially described on the Greek island of Naxos, is characterised by a triad of ARVD/C, palmoplantar keratosis and woolly hair. The incidence of ARVD/C is about 1/10 000 in the general population in the US. Point mutations in genes encoding for desmosomal proteins are the main causatives for the development of this disease. It accounts for up to 17% of all sudden cardiac death in the young.

Currently, diagnosis of an arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/ cardiomyopathy is based on standardised major and minor criteria of an International Task Force (ITF), established in 1994.11

ARVD/C is characterised by structural abnormalities predominantly of the right ventricle (RV; RV inflow tract, RV outflow tract and RV apex) associated with sudden death and ventricular arrhythmias,12–14 especially in children and young adults.

For the diagnosis of ARVD/C an electrocardiogram (ECG), echocardiography, right ventricular angiography, cardiac MRI and genetic testing are important.

The pathological hallmark of the disease is right heart dilation with focal replacement of the myocardium by fat and fibrous tissue. In some cases the left ventricle may also be involved, usually showing epicardial scarring with fat infiltration.

Myocardial sarcoidosis is a disease of young or middle-aged adults of either sex and may appear with or without evidence of disease elsewhere. Generalised cutaneous anergy and increased serum angiogensin-converting enzyme levels are helpful diagnostic adjuvants. In the absence of extracardiac signs, this disease may be difficult to diagnose. Clinical presentations of myocardial sarcoidosis are protean, including restrictive or dilated cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, ventricular arrhythmias, heart block and pericarditis. Sudden death is the initial presentation in approximately 20% of patients.15

Treatment of ventricular arrhythmias, conduction disturbances and congestive heart failure are important to consider clinically. In addition to standard antiarrhythmic pharmacological agents, implantation of pacemakers and automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, as well as radiofrequency ablation of arrhythmogenic foci, may be necessary. Long-term corticosteroid therapy may result in improvement of symptoms, reversal of electrocardiographic disturbances, complete or partial resolution of thallium perfusion defects and improvement in prognosis.

Cardiac transplantation may benefit some patients with myocardial sarcoidosis, but remains controversial because of the potential for recurrence in the allograft.16,17

Pathologically, myocardial sarcoidosis is usually characterised by interstitial fibrosis and non-necrotising granulomas with multinuclear giant cells and lymphocytic infiltration.

Helpful devices for distinguishing between an ARVD/C and a cardiac sarcoidosis may be endomyocardial biopsies, but they are only positive in up to 50% of patients with presumed myocardial involvement by sarcoid18; however, because of the patchy nature of myocardial sarcoidosis, a negative biopsy result does not automatically exclude this granulomatous disease.

In conclusion, we should always be aware, that myocardial sarcoidosis is an important clinical differential diagnosis of ARVD/C, even if all clinical, echocardiographic examinations and MRI findings are highly suggestive of an ARVD/C. Even considering the limited sensitivity cause of the mosaic-like pattern of myocardial sarcoidosis, endomyocardial biopsies may be helpful to differentiate between cardiac sarcoidosis and ARVD/C.

Learning points

The symptoms of cardiac sarcoidosis and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C) can be similar, making the differentiation between these two diseases very difficult.

The diagnostic distinction between cardiac sarcoidosis and ARVD/C is important since treatment with corticosteroids may benefit those with sarcoidosis but is not expected to be useful in cases with ARVD or ARVC.

In our case histological examination was crucial to prove the clinical diagnosis. Incorrect and false diagnosis leads to ineffective treatment, with concerns for patient quality of life.

Endomyocardial biopsies may be helpful to distinguish between cardiac sarcoidosis and ARVD/C.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Silverman KJ, Hutchins GM, Bulkley BH. Cardiac sarcoid: a clinicopathologic study of 84 unselected patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Circulation 1978; 58: 1204–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ott P, Marcus FI, Sobonya RE, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis masquerading as right ventricular dysplasia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2003; 26: 1498–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greif M, Petrakopoulou P, Weiss M, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis concealed by arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2008; 5: 231–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Froidevaux L, Levotanec I, Waeber G. A heart insufficiency treated by glucocorticoids. Praxis (Bern 1994) 2007; 96: 1643–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tandri H, Bomma C, Calkins H. Unusual presentation of cardiac sarcoidosis. Congest Heart Fail 2007; 13: 116–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiramatsu S, Tada H, Naito S, et al. Steroid treatment deteriorated ventricular tachycardia in a patient with right ventricle-dominant cardiac sarcoidosis. Int J Cardiol 2009; 132: e85–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yared K, Johri AM, Soni AV, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis imitating arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Circulation 2008; 118: e113–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiraishi J, Tatsumi T, Shimoo K, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis mimicking right ventricular dysplasia. Circ J 2003; 67: 169–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasaiwala SC, Finn C, Delpriore J, et al. Prospective study of cardiac sarcoid mimicking arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2009; 20: 473–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ladyjanskaia GA, Basso C, Hobbelink MG, et al. Sarcoid myocarditis with ventricular tachycardia mimicking ARVD/D. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2009. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKenna WJ, Thiene G, Nava A, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Task Force of the Working Group Myocardial and Pericardial Disease of the European Society of Cardiology and the Scientific Council on Cardiomyopathies of the International Society and Federation of Cardiology. Br Heart J 1994; 71: 215–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hulot JS, Jouven X, Empana JP, et al. Natural history and risk stratification of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/ cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2004; 110: 1879–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalal D, Nasir K, Bomma C, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia: a United States experience. Circulation 2005; 112: 3823–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sen-Chowdhry S, Lowe MD, Sporton SC, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. Am J Med 2004; 117: 685–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Virmani R, Bures JC, Roberts WC. Cardiac sarcoidosis: a major cause of sudden death in young individuals. Chest 1980; 77: 423–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valentine HA, Tazelaar HD, Macoviak J. Cardiac sarcoidosis: response to steroids and transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 1987; 6: 244–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oni AA, Hershberger RE, Norman DJ, et al. Recurrence of sarcoidosis in a cardiacallograft: control with augmented corticosteroids. J Heart Lung Transplant 1992; 11: 367–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rantner SJ, Fenoglio JJ, Jr, Ursell PC. Utility of endomyocardial biopsy in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. Chest 1986; 90: 528–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]