Abstract

Diverticular disease is very common and may cause symptoms of psoas irritation because of contiguous inflammation arising from the colon affecting the retroperitoneum. Retroperitoneal perforation is rare and is marked by free gas in the adjacent musculature. Rarely infection and associated gas may track into the lower limbs; however, if adequate drainage can be achieved, surgery in the unfit may be avoided. We present a case of a 79-year-old woman with retroperitoneal perforation of diverticular disease presenting with free gas in the leg musculature that was managed conservatively because of associated comorbidities and was associated with the formation of a cutaneous faecal fistula in the lower limb.

BACKGROUND

Diverticular disease is very common in the UK and other developed societies. It typically presents in the latter half of life and nearly 50% of individuals in the USA have diverticular disease by the age of 60 years.1 Up to one third of individuals with diverticular disease suffer an acute attack of inflammation (diverticulitis) and a quarter of people with diverticulitis require surgery because of sepsis, perforation or peritonitis.2 Diverticular disease may also bleed, form strictures leading to large bowel obstruction, or fistulate into nearby structures.3 Diverticulitis typically presents with left lower quadrant pain in nearly all patients (93–100% of individuals) in conjunction with a raised white cell count (69–83% of individuals), and is often associated with a fever (57–100% of individuals).3 Free intraperitoneal perforation occurs relatively commonly; however, perforation into the retroperitoneum or more rarely into the anterior abdominal wall are less common.4

We report a case of retroperitoneal diverticular perforation with free gas in the thigh tissues, requiring radical debridement, where because of comorbidities a colonic resection was not possible, and a faecal fistula developed over the left lateral thigh which has been managed with a stoma appliance.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 79-year-old woman presented to the emergency general surgical service at our institution with a short history of left sided abdominal pain, fever and swelling in the left upper thigh. She had previously experienced mild episodes of left iliac fossa pain suggestive of diverticular disease. Clinical examination revealed a pyrexia and signs consistent with systemic sepsis. Plain chest and abdominal radiographs were performed, free gas was not seen on the chest radiograph, but the plain abdominal film identified left sided retroperitoneal gas. A full blood count revealed a raised white cell count (>15.0×109/l) with a predominance of neutrophils (>70%) and C reactive protein >100 mg/l. Intravenous access was established and intravenous fluids, analgesia and intravenous antibiotics (cefuroxime 750 mg three times daily and metronidazole 500 mg three times daily) were administered.

INVESTIGATIONS

Systemic blood was cultured at the time of presentation, but this did not yield any organisms. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen, pelvis and lower limbs was undertaken; this revealed free gas within the retroperitoneum, the left gluteal region (fig 1), and extending into the left upper thigh (fig 2). A faeculent fistula arose in the lateral thigh and culture of the material discharged revealed enterococci and anaerobic faecal organisms, but no Clostridium species.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography (CT) image of the pelvis showing subcutaneous gas within the gluteal muscle compartment.

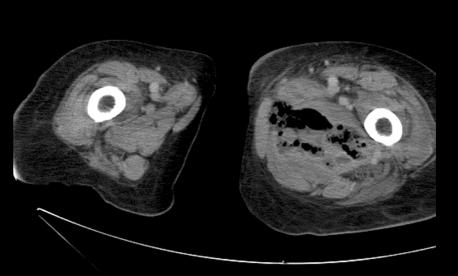

Figure 2.

CT image of the lower limbs showing subcutaneous gas within the left medial thigh.

TREATMENT

The patient had significant comorbidities and expressed a wish not to undergo surgery. Therefore a conservative approach was pursued. The systemic symptoms settled with antibiotic treatment. However, an inflamed area appeared on the lateral upper thigh, which then broke down and a faeculent discharge was released. The faecal fistula persisted and was managed with a stoma appliance.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Investigation of the left colon endoscopically and with retrograde contrast study was considered; however, there were significant concerns that this may cause a further perforation or precipitate additional sepsis and so a decision was made to undertake clinical and CT follow-up. Three years later the patient remains well and continues to manage the faecal fistula with a stoma bag.

DISCUSSION

Diverticular disease is very common and is increasingly affecting a younger population group in the developed world.5 It presents most commonly with left lower quadrant pain, local peritonism or frank peritonitis because of colonic perforation requiring emergency surgery.

Colonic diverticulae arise at points of weakness in the colonic wall typically where arteries enter the colon. It is suggested that low dietary fibre causes a reduction in stool bulk6; the colon must generate high luminal pressure to propel this hard, dry, small volume stool along its length. These high pressures cause ballooning of the colonic mucosa at areas of weakness and over time result in the development of diverticulae. A high fibre diet may prevent further diverticulae forming, although it has not, as yet, been shown to reverse the presence of diverticular disease or alter the risk of complications.7 Risk factors for diverticular disease additionally include female sex, smoking and alcohol.

Several pathophysiological abnormalities related to parasympathetic nervous system function have also been noted in colonic specimens with diverticular disease. These suggest increased parasympathetic system activity consistent with the increased colonic pressures seen in diverticular disease. Changes include upregulation of smooth muscle muscarinic M3 receptors, increased in vitro sensitivity to acetylcholine, and reduced activity of smooth muscle choline acetyltransferase resulting in higher local acetylcholine concentrations. Although well described, the mechanism leading to these changes remains unclear.8

Less commonly, retroperitoneal perforation occurs with only 10 published cases of gas tracking into the lower limb. This requires a much greater level of clinical suspicion, especially in younger patients who have higher rates of complicated diverticular disease.9 Psoas irritation may direct the clinician to consider a retroperitoneal collection or perforation, and early cross sectional imaging is recommended in these individuals.

The formation of gas in the tissues in this setting reflects severe sepsis and very often indicates the presence of Clostridium species. The damaged tissue present in perforated diverticular disease provides an ideal environment to for clostridial spores to germinate. The organism rapidly produces a range of toxins including collagenases that break down connective tissue and aid the spread of infection. In addition, a number of exotoxins that cause impairment and destruction of white cells, haemolysis, cell wall injury and direct vascular injury are also produced.10,11 The organism, in combination with synergistic infection by other gut flora, rapidly produces gas and because of the collagenase activity sepsis may track into distant sites such as the lower limb.12

This rapid progression of infection means aggressive and early debridement is critical. In older patients, comorbidities, although often significant, should not dissuade the clinician from this radical debridement if sepsis has spread into the lower limb with gas gangrene. Surgery may be life saving and after the acute events have been managed radical colonic resection may still be avoidable in those with multiple comorbidities. Interestingly, necrotising fasciitis did not supervene in our patient. This may be explained by the fact that Clostridium species were not identified in the fistula discharge that was cultured from our patient, allowing us to pursue a conservative approach and spare our patient radical, high risk, surgical intervention.

Learning points

Retroperitoneal extension of inflammation due to diverticular disease occurs occasionally and produces symptoms of psoas irritation.

Retroperitoneal perforation is less common; however, it will cause free gas within the adjacent tissue.

Patients with evidence of necrotising fasciitis require emergency life saving radical surgical intervention.

Extension of gas into the lower limb is very rare; however, if adequate drainage can be achieved and there is no evidence of necrotising fasciitis, a conservative approach in unfit patients can be pursued.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Wong WD, Wexner SD, Lowry A, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis—supporting documentation. The Standards Task Force. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 290–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salem L, Flum DR. Primary anastomosis or Hartmann’s procedure for patients with diverticular peritonitis? A systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47: 1953–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bordeianou L, Hodin R. Controversies in the surgical management of sigmoid diverticulitis. J Gastrointest Surg 2007; 11: 542–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Secil M, Topacoglu H. Retroperitoneal necrotizing fasciitis secondary to colonic diverticulitis. J Emerg Med 2008; 34: 95–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pautrat K, Bretagnol F, Huten N, et al. Acute diverticulitis in very young patients: a frequent surgical management. Dis Colon Rectum 2007; 50: 472–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Painter NS, Burkitt DP. Diverticular disease of the colon: a deficiency disease of Western civilization. BMJ 1971; 2: 450–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ornstein MH, Littlewood ER, Baird IM, et al. Are fibre supplements really necessary in diverticular disease of the colon? BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1981; 282: 1629–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golder M, Burleigh DE, Belai A, et al. Smooth muscle cholinergic denervation hypersensitivity in diverticular disease. Lancet 2003; 361: 1945–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McConnell EJ, Tessier DJ, Wolff BG. Population-based incidence of complicated diverticular disease of the sigmoid colon based on gender and age. Dis Colon Rectum 2003; 46: 1110–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens DL, Tweten RK, Awad MM, et al. Clostridial gas gangrene: evidence that alpha and theta toxins differentially modulate the immune response and induce acute tissue necrosis. J Infect Dis 1997; 176: 189–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDonel JL. Clostridium perfringens toxins (type A, B, C, D, E). Pharmacol Ther 1980; 10: 617–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.San Ildefonso A, Maruri I, Facal C, et al. Clostridium septicum infection associated with perforation of colon diverticulum. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2002; 94: 361–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]