Abstract

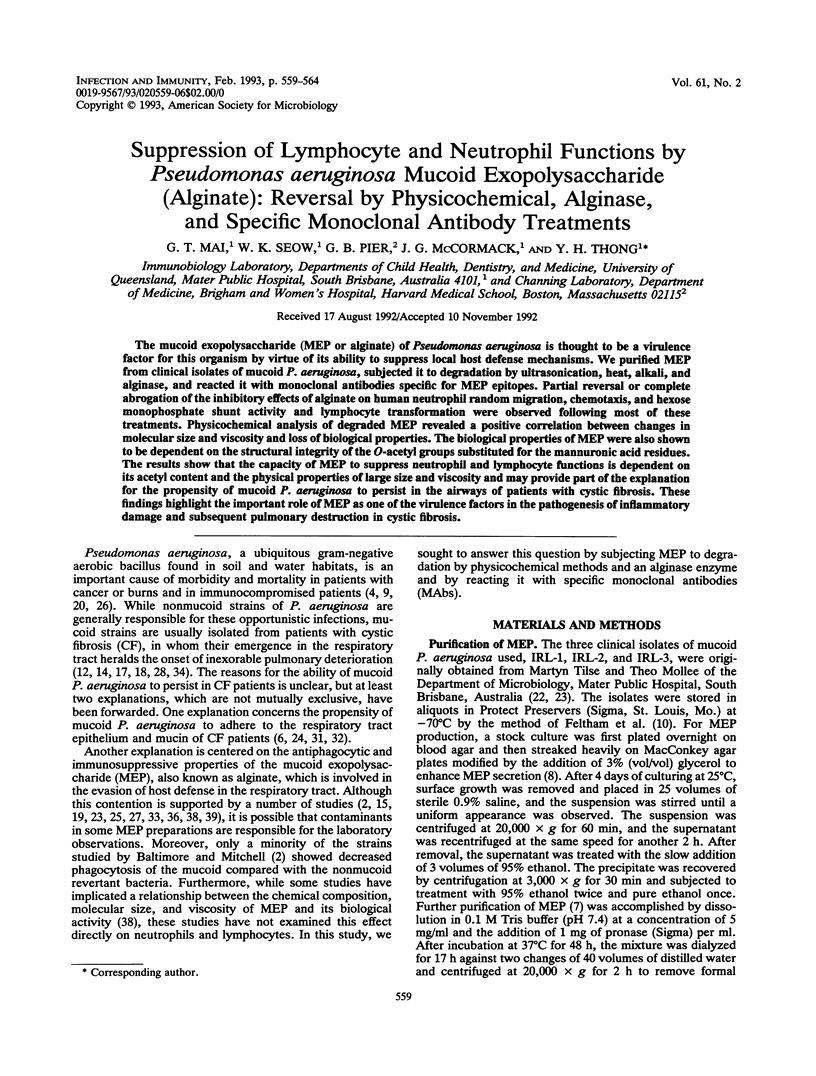

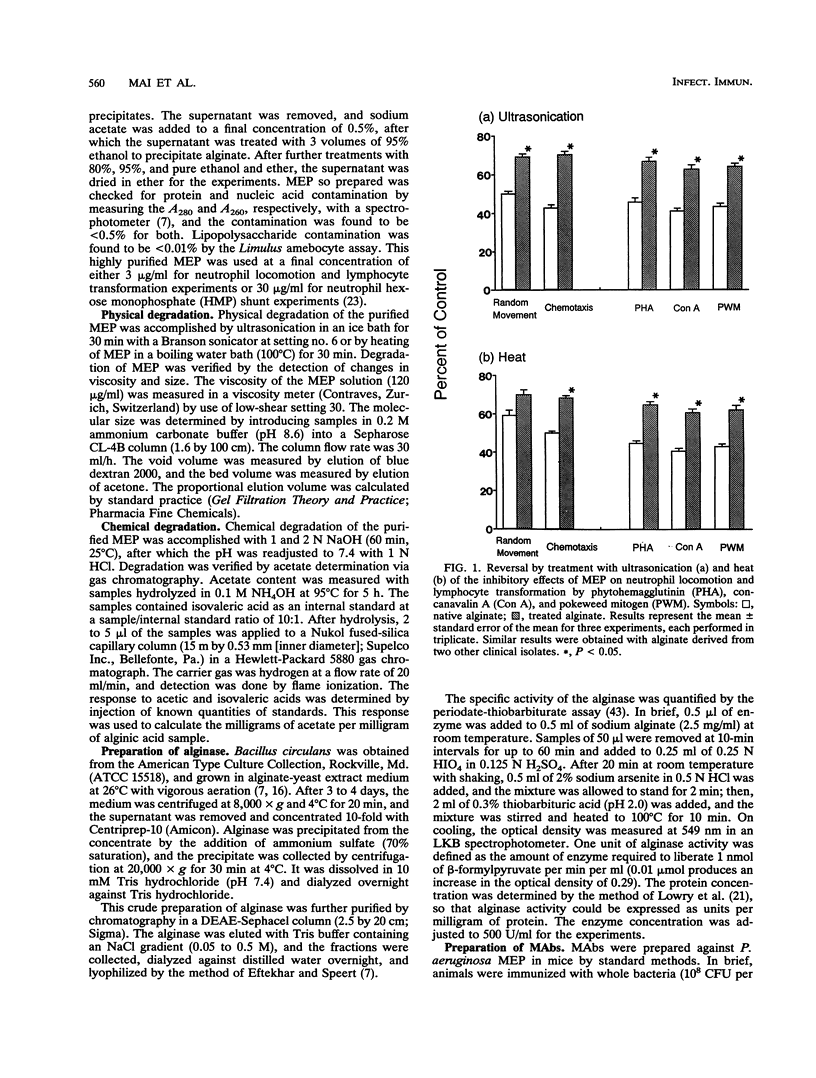

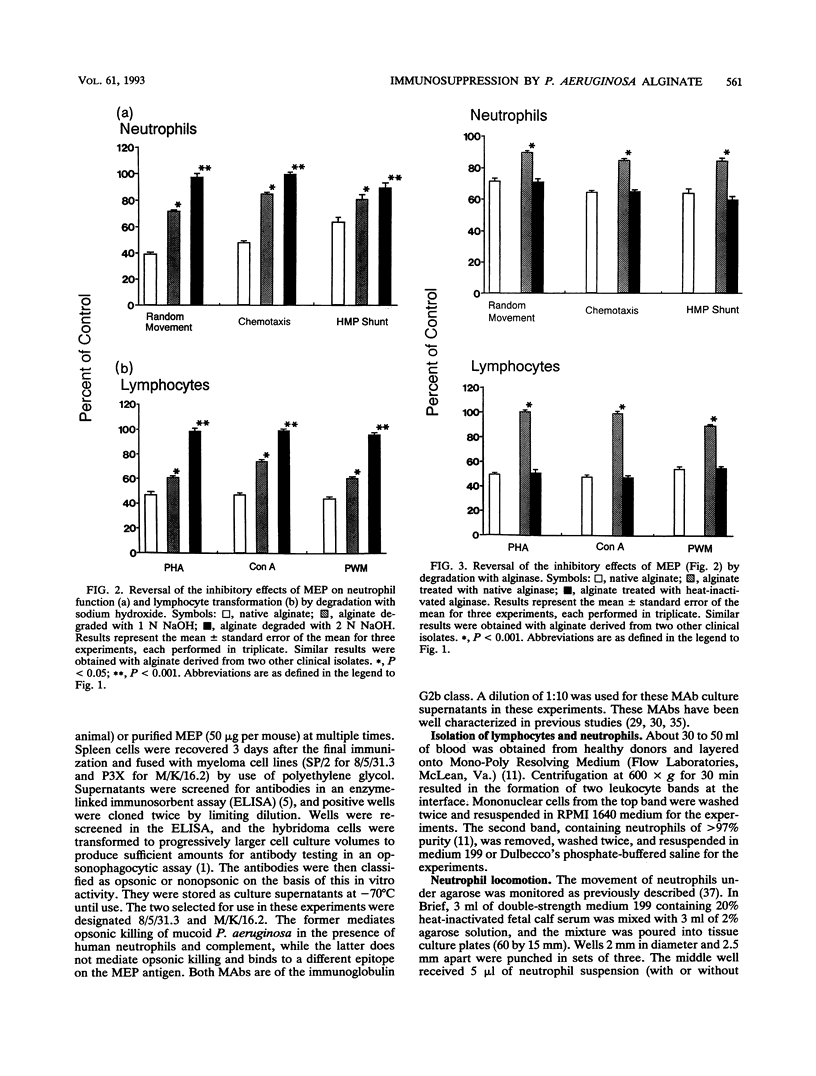

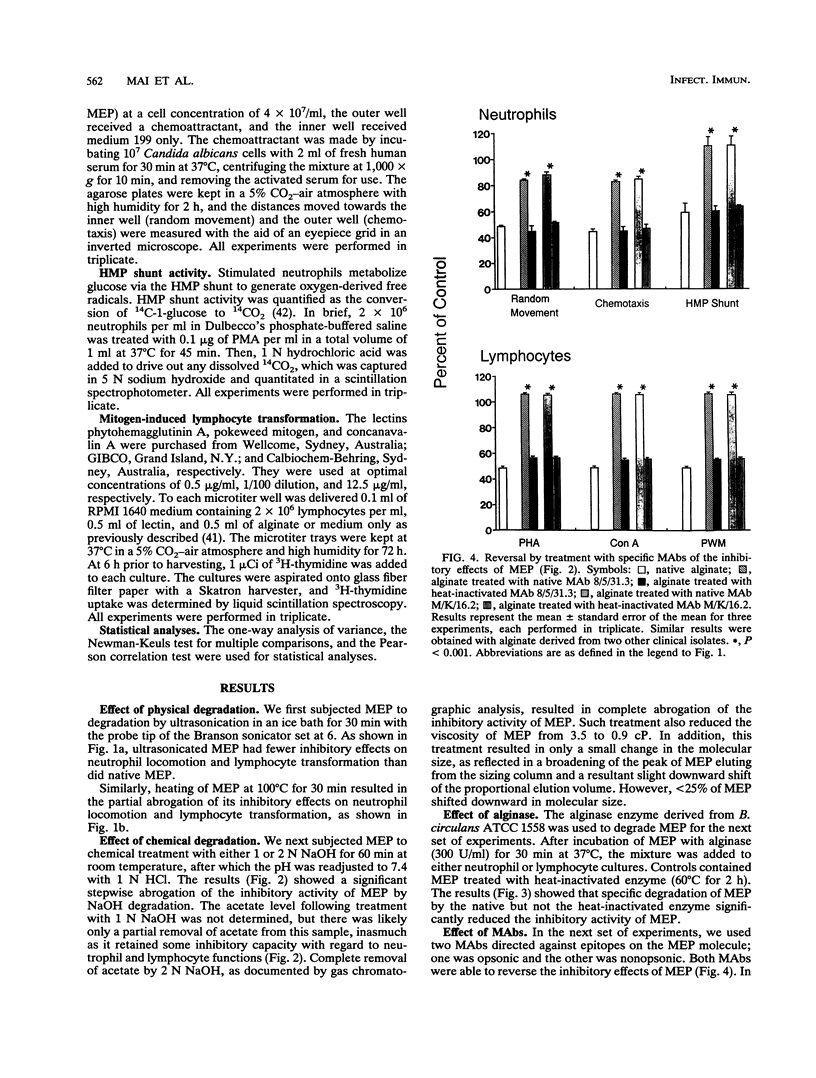

The mucoid exopolysaccharide (MEP or alginate) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is thought to be a virulence factor for this organism by virtue of its ability to suppress local host defense mechanisms. We purified MEP from clinical isolates of mucoid P. aeruginosa, subjected it to degradation by ultrasonication, heat, alkali, and alginase, and reacted it with monoclonal antibodies specific for MEP epitopes. Partial reversal or complete abrogation of the inhibitory effects of alginate on human neutrophil random migration, chemotaxis, and hexose monophosphate shunt activity and lymphocyte transformation were observed following most of these treatments. Physicochemical analysis of degraded MEP revealed a positive correlation between changes in molecular size and viscosity and loss of biological properties. The biological properties of MEP were also shown to be dependent on the structural integrity of the O-acetyl groups substituted for the mannuronic acid residues. The results show that the capacity of MEP to suppress neutrophil and lymphocyte functions is dependent on its acetyl content and the physical properties of large size and viscosity and may provide part of the explanation for the propensity of mucoid P. aeruginosa to persist in the airways of patients with cystic fibrosis. These findings highlight the important role of MEP as one of the virulence factors in the pathogenesis of inflammatory damage and subsequent pulmonary destruction in cystic fibrosis.

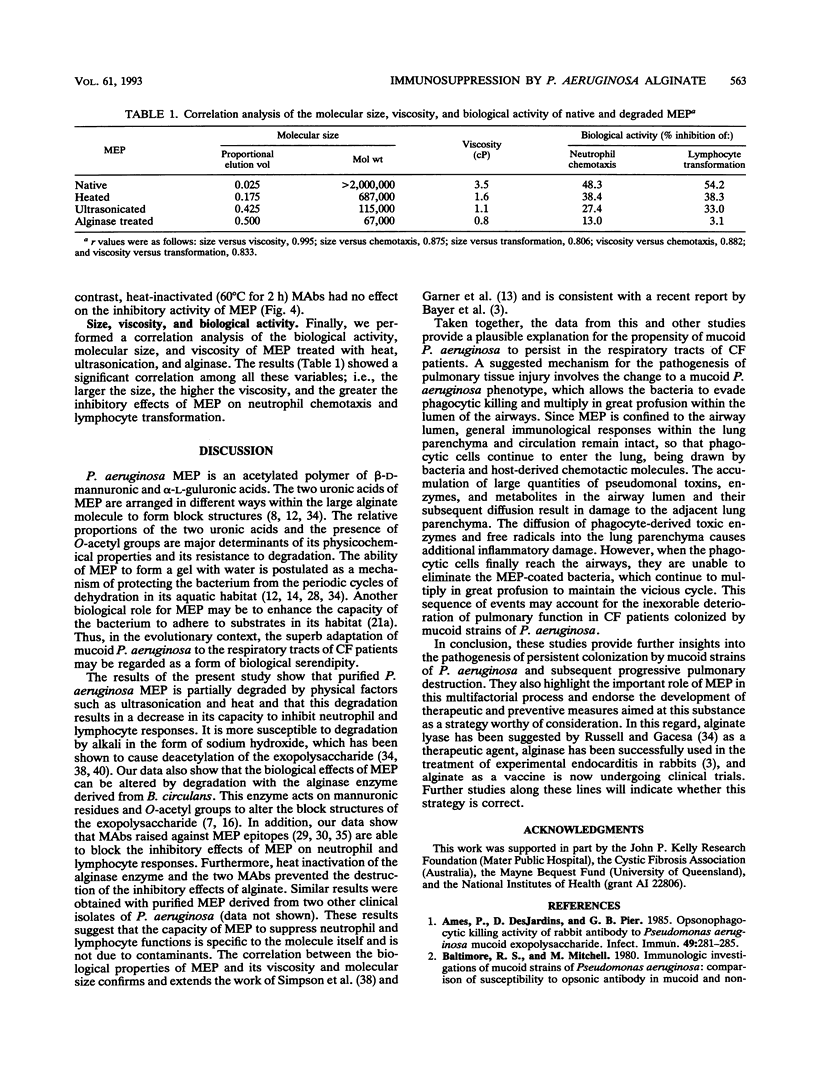

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ames P., DesJardins D., Pier G. B. Opsonophagocytic killing activity of rabbit antibody to Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1985 Aug;49(2):281–285. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.281-285.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer A. S., Park S., Ramos M. C., Nast C. C., Eftekhar F., Schiller N. L. Effects of alginase on the natural history and antibiotic therapy of experimental endocarditis caused by mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1992 Oct;60(10):3979–3985. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.3979-3985.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergan T. Pathogenetic factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1981;29:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan L. E., Kureishi A., Rabin H. R. Detection of antibodies to Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate extracellular polysaccharide in animals and cystic fibrosis patients by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1983 Aug;18(2):276–282. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.2.276-282.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doig P., Smith N. R., Todd T., Irvin R. T. Characterization of the binding of Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate to human epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1987 Jun;55(6):1517–1522. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.6.1517-1522.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eftekhar F., Speert D. P. Alginase treatment of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa enhances phagocytosis by human monocyte-derived macrophages. Infect Immun. 1988 Nov;56(11):2788–2793. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.11.2788-2793.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans L. R., Linker A. Production and characterization of the slime polysaccharide of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1973 Nov;116(2):915–924. doi: 10.1128/jb.116.2.915-924.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigin R. D., Shearer W. T. Opportunistic infection in children. II. In the compromised host. J Pediatr. 1975 Nov;87(5):677–694. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(75)80289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltham R. K., Power A. K., Pell P. A., Sneath P. A. A simple method for storage of bacteria at--76 degrees C. J Appl Bacteriol. 1978 Apr;44(2):313–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1978.tb00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante A., Thong Y. H. Optimal conditions for simultaneous purification of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear leucocytes from human blood by the Hypaque-Ficoll method. J Immunol Methods. 1980;36(2):109–117. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(80)90036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner C. V., DesJardins D., Pier G. B. Immunogenic properties of Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1990 Jun;58(6):1835–1842. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1835-1842.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govan J. R., Harris G. S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and cystic fibrosis: unusual bacterial adaptation and pathogenesis. Microbiol Sci. 1986 Oct;3(10):302–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso R. J., Ganguly R., Breen J. F. Inhibition of yeast phagocytosis in macrophage cultures treated with slime polysaccharide purified from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Leukoc Biol. 1984 Dec;36(6):771–774. doi: 10.1002/jlb.36.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J. B., Doubet R. S., Ram J. Alginase enzyme production by Bacillus circulans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984 Apr;47(4):704–709. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.4.704-709.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubesch P., Lingner M., Grothues D., Wehsling M., Tümmler B. Strategies of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to colonize and to persist in the cystic fibrosis lung. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1988;143:77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Learn D. B., Brestel E. P., Seetharama S. Hypochlorite scavenging by Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate. Infect Immun. 1987 Aug;55(8):1813–1818. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.8.1813-1818.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai G. T., Seow W. K., McCormack J. G., Thong Y. H. Direct activation of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1989;90(4):358–363. doi: 10.1159/000235053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai G. T., Seow W. K., McCormack J. G., Thong Y. H. In vitro immunosuppressive and anti-phagocytic properties of the exopolysaccharide of mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1990;92(2):105–112. doi: 10.1159/000235199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus H., Baker N. R. Quantitation of adherence of mucoid and nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa to hamster tracheal epithelium. Infect Immun. 1985 Mar;47(3):723–729. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.3.723-729.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshulam T., Obedeanu N., Merzbach D., Sobel J. D. Phagocytosis of mucoid and nonmucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1984 Aug;32(2):151–165. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(84)90117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu H. C. The role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983 May;11 (Suppl B):1–13. doi: 10.1093/jac/11.suppl_b.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver A. M., Weir D. M. Inhibition of bacterial binding to mouse macrophages by Pseudomonas alginate. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1983 Apr;10(4):221–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pier G. B., Grout M., Desjardins D. Complement deposition by antibodies to Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide (MEP) and by non-MEP specific opsonins. J Immunol. 1991 Sep 15;147(6):1869–1876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pier G. B. Pulmonary disease associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: current status of the host-bacterium interaction. J Infect Dis. 1985 Apr;151(4):575–580. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pier G. B., Small G. J., Warren H. B. Protection against mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in rodent models of endobronchial infections. Science. 1990 Aug 3;249(4968):537–540. doi: 10.1126/science.2116663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramphal R., Guay C., Pier G. B. Pseudomonas aeruginosa adhesins for tracheobronchial mucin. Infect Immun. 1987 Mar;55(3):600–603. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.3.600-603.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramphal R., Pier G. B. Role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide in adherence to tracheal cells. Infect Immun. 1985 Jan;47(1):1–4. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.1.1-4.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhen R. W., Holt P. G., Papadimitriou J. M. Antiphagocytic effect of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exopolysaccharide. J Clin Pathol. 1980 Dec;33(12):1221–1222. doi: 10.1136/jcp.33.12.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell N. J., Gacesa P. Chemistry and biology of the alginate of mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Mol Aspects Med. 1988;10(1):1–91. doi: 10.1016/0098-2997(88)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber J. R., Pier G. B., Grout M., Nixon K., Patawaran M. Induction of opsonic antibodies to Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide by an anti-idiotypic monoclonal antibody. J Infect Dis. 1991 Sep;164(3):507–514. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.3.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzmann S., Boring J. R. Antiphagocytic Effect of Slime from a Mucoid Strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1971 Jun;3(6):762–767. doi: 10.1128/iai.3.6.762-767.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seow W. K., Ferrante A., Li S. Y., Thong Y. H. Antiphagocytic and antioxidant properties of plant alkaloid tetrandrine. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1988;85(4):404–409. doi: 10.1159/000234542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J. A., Smith S. E., Dean R. T. Alginate inhibition of the uptake of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by macrophages. J Gen Microbiol. 1988 Jan;134(1):29–36. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-1-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J. A., Smith S. E., Dean R. T. Scavenging by alginate of free radicals released by macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;6(4):347–353. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thong Y. H., Ferrante A. Inhibition of mitogen-induced human lymphocyte proliferative responses by tetracycline analogues. Clin Exp Immunol. 1979 Mar;35(3):443–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thong Y. H., Rencis V. Bilirubin inhibits hexose-monophosphate shunt activity of phagocytosing neutrophils. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1977 Nov;66(6):757–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1977.tb07985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEISSBACH A., HURWITZ J. The formation of 2-keto-3-deoxyheptonic acid in extracts of Escherichia coli B. I. Identification. J Biol Chem. 1959 Apr;234(4):705–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]