Abstract

The use of new generation multi-kinase inhibitors for the treatment of various malignancies has brought unique and previously unrecognised cutaneous reactions to the attention of dermatologists. We report the case of a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who presented to our dermatology clinic with eruptive squamous cell carcinomas with keratoacanthomatous features and painless palmoplantar hyperkeratosis while taking sorafenib (Nexavar). Dermatological toxicity from sorafenib has been well described in the literature. Herein we describe a combination of unusual symptoms due to sorafenib.

Background

Sorafenib is a new generation oral multi-kinase inhibitor approved by the FDA in 2005 for treating metastatic renal cell carcinoma, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, and metastatic melanoma. It is also used to delay the progression of advanced solid organ malignancies.1 Specifically, it functions by inhibiting C-RAF, B-RAF and a mutant B-RAF, which are involved in the RAS/RAF signalling pathway, an important mediator of tumour cell proliferation and angiogenesis. It also inhibits VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, PDGFRβ and C-Kit, which are tyrosine kinases partially responsible for neovascularisation and tumour progression.2

Sorafenib has been associated with many dermatological toxic effects including erythaema, hand-foot skin reaction, alopecia, pruritis, xerosis, exfoliative dermatitis, acneiform eruptions, flushing, eczema and erythaema multiforme.3 Such skin toxicities have been implicated as potentially useful markers for treatment efficacy and have also been correlated with positive medical outcomes and survival. For example, when dermatological toxic effects and diarrhoea were observed in patients undergoing treatment with sorafenib, an increase in time to tumour progression was observed.4

Since there is proven efficacy of sorafenib in delaying tumour progression, it is often necessary to continue treatment despite the aforementioned side effects. As such, it is necessary for clinicians to be aware of the more common skin toxicities, in addition to the more obscure side effects of sorafenib treatment. With greater knowledge of such events, unnecessary work-ups and undue stress will be avoided, while treatment can be lengthened with improved outcomes.

Herein we report the case of a patient who presented with two atypical cutaneous side effects that have been reported only once previously but never in the same patient at the same time.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old white male presented to the dermatology clinic with a chief complaint of multiple crusted lesions found scattered over his body. New lesions had continued to develop on his arms and torso over the last few months. He also complained of greatly callused palmar, plantar and digital surfaces that arose abruptly over a period of 2 weeks. He was unable to bear weight due to pain from his feet.

Six months previously, the patient had been diagnosed with clear cell renal cell carcinoma with metastatic disease to the lungs. Treatment with sorafenib 200 mg twice daily was initiated for his metastatic disease. Shortly after beginning therapy he developed intense burning, tingling and itching on his scalp with concomitant patchy hair loss. After 4 weeks, the patient increased the dosage of sorafenib to 600 mg 3 days a week while continuing 400 mg on alternate days. This resulted in an increase in already present symptoms. Furthermore, he began to experience exquisite tenderness in his plantar surfaces with thick calluses appearing. Eventually, he was unable to walk because of the pain. He found immediate relief of this symptom after a podiatric visit where the calluses were shaved off. Thickened calluses also presented on his palmar and digital surfaces but were painless. The patient further increased his sorafenib intake to 600 mg for 6 out of 7 days per week. Within 2 weeks he found numerous crusting lesions emerging suddenly on his body. He was then referred to the dermatologist.

The patient, in addition to sorafenib, was taking alprazolam, atenolol, an amlodipine/benazepril combination and 81 mg daily aspirin. He denied any manual labour or increase in work with his hands and feet. He also denied excessive sun exposure, radiation exposure, HPV infection or trauma. His history was positive for a 16-year history of smoking which he quit in 1978, and chemical exposure to silica and freon, both a result of employment prior to 1980. Currently, he holds a desk job. There was no family history of dermatological or genetic disease.

Physical exam revealed several firm, pink-to-red, round, thick, dome shaped plaques with central crusting that measured up to 2×2 cm (figure 1). These plaques were found on his upper torso and upper extremities. There were also numerous smaller pink plaques with hard central crusts on the dorsum of both hands. The finger tips, palmar surfaces of the hands and lateral surfaces of the fingers were found to have multiple yellow-to-brown hyperkeratotic plaques that were firm and rough to palpation, suggesting a callus (figure 2). The plantar surfaces of both feet were also extensively covered with similar broad plaques suggestive of callosities (figure 3).

Figure 1.

Pink-to-red, round, thick, dome shaped plaques with central crusting that measured up to 2×2 cm.

Figure 2.

Yellow-to-brown hyperkeratotic plaques, palmar surface.

Figure 3.

Yellow-to-brown hyperkeratotic plaques, plantar surface.

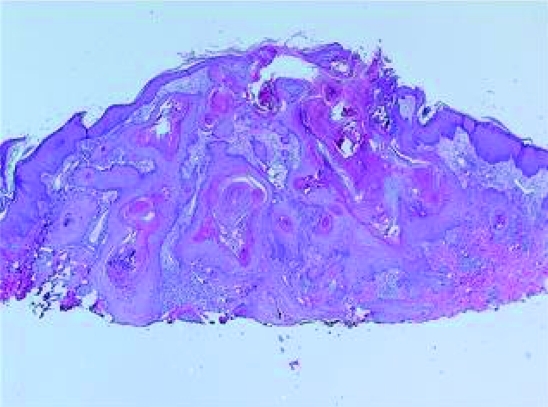

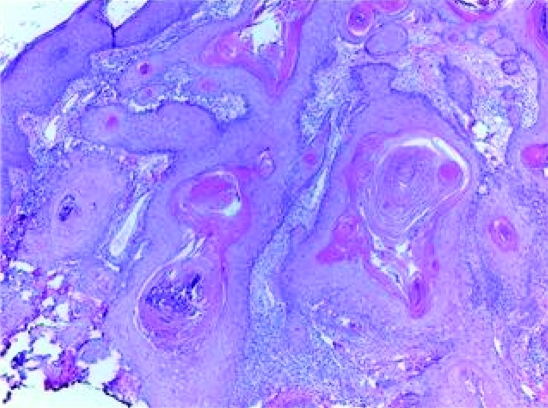

Five scoop-shave biopsies were obtained. The pathology on all biopsies showed similar histological features on H&E (figures 4 and 5). There was symmetrical epidermal proliferation with a central keratotic plug and peripheral collarette. The lesion had both an exophytic and endophytic component. The crater walls were formed by epidermal proliferation thrown in multiple folds and invaginations. The deeper parts of growth had a focal infiltrative pattern. There was only minimal pleomorphism, and most of the lesional cells were well differentiated squamous cells with pale staining and eosinophilic, glassy cytoplasm. Scattered keratin horn cysts, keratin pearls and neutrophilic microabscesses were identified. Rare typical mitotic figures were identified. These specimens were consistent with the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma with keratoacanthomatous features. The palmar and plantar surfaces were not biopsied.

Figure 4.

Low power photomicrograph showing a central crater filled with a keratin plug and epidermis thrown into many folds and invaginations.

Figure 5.

Higher power photomicrograph showing a focal infiltrative pattern and well differentiated epithelium with characteristic pallor and microabscesses.

Treatment of the multiple squamous cell carcinomas with keratoacanthomatous features consisted of excision of some, electrodessication and curettage of other large lesions, and aggressive cryotherapy of the smaller ones. The sorafenib dose was cut back to 200 mg each day resulting in greatly reduced occurrence of keratoacanthomatous eruption and improvement in palmoplantar hyperkeratosis. Four months after starting sorafenib, the patient discontinued it. Within a few weeks, the hyperkeratosis of his palms and soles decreased by about 90% and there have been no new squamous cell carcinomas with keratoacanthomatous features.

Treatment

See case presentation section above.

Outcome and follow-up

See case presentation section above.

Discussion

Hand-foot skin reaction is a principal toxicity in sorafenib treatment, occurring in 30% of the patient population.5 It has also commonly been described in conjunction with other chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin, fluorouracil, capecitiabine and cytarabine.6 The clinical picture includes exquisite tenderness and paresthaesias of palmar and plantar surfaces, often called erythrodysesthesia. Other reactions include erythaematous changes with oedema followed by desquamation. There may be varying manifestations of such lesions on physical exam, as in the case of our patient who experienced pain and paresthaesia of the feet but no oedema or erythaema.

One additional cutaneous reaction to sorafenib has been reported which differs from classic hand-foot syndrome (and its interchangeable terms erythrodysesthesia and acral erythaema). The presentation is that of painless localised plaques exhibiting epidermal hyperplasia surrounded by a rim of hypopigmentation and more peripheral erythaema. Such lesions were described as being callus like.7 Our patient’s palmar presentation is similar to this unusual finding, manifesting as thick, painless palmar hyperkeratosis, excluding the peripheral erythaema and hypopigmentation.

Acquired palmoplantar keratodermas, which are non-hereditary, non-frictional hyperkeratoses of the palms and soles, have several potential causes including drugs, malnutrition, chemicals, systemic disease, infectious disease and malignancy.8 Acquired palmoplantar keratodermas with related internal malignancy including carcinoma of the bronchus, lung, oesophagus and stomach, have been described.9–11 Although our patient had metastatic lung disease, it is not likely that he presented with hyperkeratosis as a result of the cancer, considering that skin manifestations tend to precede discovery of the neoplasm by a few months. More likely, the keratoderma was drug related, given that the symptoms began and regressed according to his intake of sorafenib. Therefore, we add further evidence of the distinctive manifestation of painless hyperkeratosis as a result of the use of this multi-kinase inhibitor.7

Furthermore, squamous cell carcinomas with keratoacanthomatous features associated with sorafenib have been described only once previously, where they occurred in less than 3% of the patient population treated.12 The presumed pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinomas with keratoacanthomatous features is multifaceted. Implicated causes include chronic UV exposure, chemical carcinogens (with smokers appearing to be more affected than non-smokers), trauma, HPV infection, genetic predisposition and immunosuppression.13–15 Sorafenib is not an immunosuppressive agent and, thus, has not been correlated with opportunistic infections. However, due to the important role in epithelial biology that the epidermal growth factor (EGFR) and its downstream activation of tyrosine kinase activity play,16 it may be plausible that sorafenib has some influence upon these cellular activities.

Due to the unusual findings from sorafenib and other kinase inhibitors, it is important to be aware of their cutaneous adverse events so as to avoid unnecessary investigations and optimise treatment. Current recommendations for skin toxicities are based on the clinical grade of the adverse event. Most toxicities are grade 1–2, as graded by the Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) v4.0 of the National Cancer Institute,17 which allows for continuing treatment with supportive care. Patients with grade 1–2 hand-foot syndrome for example, benefit from manicures and pedicures, while patients with rash/desquamation were able to continue chemotherapeutic treatment with application of topical steroids for the control of symptoms.18 Toxicities that reach a grade of 3–4 usually require temporary or permanent interruption of treatment. For example, interruption of therapy is recommended for the first and second occurrences of grade 3 skin toxicities for 1–2 weeks until symptoms return to grade 0–1. This is followed by resumption of treatment with dose modification. Upon a third recurrence of grade 3 symptoms, sorafenib should be discontinued.19 Understandably, individual toxicity profiles may override these recommendations.

Overall, of the three kinase inhibitors (sorafenib, sunitinib, temsirolimus) available for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma, sorafenib causes the fewest grade 3 or higher side effects of all organ systems at its recommended dose, while sunitinib causes the most.18 Each drug possesses a unique toxicity profile. Common grade 3 or 4 side effects with sorafenib include lymphopaenia, hypophosphataemia, elevated lipase, hand-foot syndrome and mucositis/stomatitis. With suntinib elevated lipase, neutropaenia, lymphopaenia, hypertension and fatigue/asthaenia are common. For temsirolimus, common grade 3 or 4 side effects include anaemia, hyperglycaemia, fatigue/asthaenia, dyspnoea, and hypophosphataemia.20 Despite this, the selection of optimal treatment is based on indications for therapy and efficacy rather than the most favourable overall toxicity profile.

Fortunately, most adverse events acquired from the use of sorafenib and other kinase inhibitors, both cutaneous and non-cutaneous, can be easily managed with a combination of medical treatment and supportive care. As the adverse reactions become more severe, a trial of therapy interruption followed by dose reduction usually proves successful with reversal of symptoms. Thus, continuation of therapy is best maximised by extensive use of preventative monitoring, early intervention and appropriate treatment of adverse events, permitting patients to continue receiving the benefit that sorafenib offers.

Learning points

Clinicians should to be aware of the multiple skin toxicities associated with sorafenib and other kinase inhibitors so that unnecessary investigations are avoided.

Hand-foot syndrome is the principal skin toxicity of sorafenib and is described as exquisite tenderness and paresthaesias of palmar and plantar surfaces, and occasionally erythaematous changes followed by desquamation; painless hyperkeratosis appears to be a distinct adverse skin reaction.

Clinicians must weigh the potential anti-cancer benefits with the adverse skin reactions when treating their patients, and use recommended guidelines for continuation of treatment.

Patients may often continue treatment despite skin toxicities given the implication that they are useful markers for treatment efficacy.

Preventative monitoring, early intervention and appropriate treatment of adverse events allow patients to continue to receive the benefits of kinase inhibitor use despite adverse events.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Escudier B, Lassau N, Angevin E, et al. Phase I trial of sorafenib in combination with IFN alpha-2ª in patients with unresectable and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma or malignant melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 1801–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, et al. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 7099–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayer Pharmaceuticals Nexavar (sorafenib) tablets 200 mg (product information). West Haven, CT: Bayer Pharmaceuticals; Available at: http://www.univgraph.com/bayer/inserts/nexavar.pdf (accessed 3 March 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez-Soler R. Can rash associated with HER1/EGFR inhibition be used as a marker of treatment outcome? Oncology (Williston Park) 2003; 17(Suppl 12): 23–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kane RC, Farrell AT, Saber H, et al. Sorafenib for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 7271–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagore E, Insa A, Sanmartin O. Antineoplastic therapy-induced palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia (‘hand-foot’) syndrome. Incidence, recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 2000; 1: 255–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beldner M, Jacobson M, Burges GE, et al. Localized palmar-plantar epidermal hyperplasia: a previously undefined dermatologic toxicity to sorafenib. Oncologist 2007; 12: 1178–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel S, Zirwas M, English JC. Acquired palmoplantar keratoderma. Am J Clin Dermatol 2007; 8: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanna SK, Agnone FA, Leibowitz AI, et al. Nonfamilial diffuse palmoplantar keratoderma associated with bronchial carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 28: 295–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engin H, Akdogan A, Altundag O, et al. Non-small-cell lung cancer with nonfamilial diffuse palmoplantar keratoderma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2002; 21: 45–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murata I, Ogami Y, Nagai Y, et al. Carcinoma of the stomach with hyperkeratosis palmaris et plantaris and acanthosis of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 1998; 93: 449–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong HH, Cowen EW, Azad NS, et al. Keratoacanthomas associated with sorafenib therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56: 171–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghadially FN, Barton G, Kerridge D, et al. The etiology of keratoacanthoma. Cancer 1963; 16: 603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pattee SF, Silvis NG. Keratoacanthoma developing in sites of previous trauma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003; 48(Suppl): S35–S38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forslund O, DeAngelis PM, Beigi M, et al. Identification of human papillomavirus in keratoacanthomas. J Cutan Pathol 2003; 30: 423–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albaell J, Rojo F, Averbuch S, et al. Pharmacodynamic studies of the epidermal alterations in patients treated with ZD1839 (Iressa), an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Br J Dermatol 2002; 147: 598–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.. West Haven, CT: Bayer Pharmaceuticals Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) v4.0. Published 28 May 2009. Available at http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev4.pdf (accessed 25 June 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhojani N, Jeldres C, Patard JJ, et al. Toxicities associated with the administration of sorafenib, sunitinib, and temsirolimus and their management in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2008; 53: 917–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutson TE, Figlin RA, Kuhn JG, et al. Targeted therapies for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an overview of toxicity and dosing strategies. Oncologist 2008; 13: 1084–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guevremont C, Alasker A, Karakiewicz PI. Management of sorafenib, sunitinib, and temsirolimus toxicity in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2009; 3: 170–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]