Abstract

Glatiramer acetate, a mixture of synthetic polypeptides able to prevent autoimmune encephalomyelitis in experimental models, is used as a treatment for patients with active relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. We report one case of glatiramer acetate induced hepatitis. Liver biopsy was consistent with a diagnosis of drug induced hepatitis and alanine aminotransferase returned to normal values after treatment discontinuation. The present case should serve as a warning that glatiramer acetate may cause acute liver disease.

BACKGROUND

Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone, Sanofi-Aventis, Diegem, Belgium), a mixture of synthetic polypeptides able to prevent autoimmune encephalomyelitis in experimental models, has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as a treatment for patients with active relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (MS).1 Up to now, no case of glatiramer acetate induced hepatitis has been reported. We describe a patient who developed severe liver injury while on glatiramer acetate.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 52-year-old woman was referred for a rise in liver enzymes. She had no relevant past medical history. She had essential hypertension and had been receiving potassium canrenoate 100 mg/day starting in the year 2000 and lisinopril 20 mg/day plus hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg/day since 2005. She also took ebastine 10 mg/day from 2003 on and desloratadine 5 mg/day since 2006 for allergic rhinitis, and a micronised purified flavonoid fraction (Daflon, Servier, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France) for vascular incompetence of the lower legs since 1988. She had no history of alcohol abuse. MS was diagnosed in June 2007. On 15 July 2007, glatiramer acetate was started at 20 mg subcutaneously once a week. On 10 September, she received a 5 day course of methylprednisolone 1 g/day to control the acute phase of MS (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Treatments and serum alanine aminotransferase activity in a patient with glatiramer acetate induced acute hepatitis.

INVESTIGATIONS

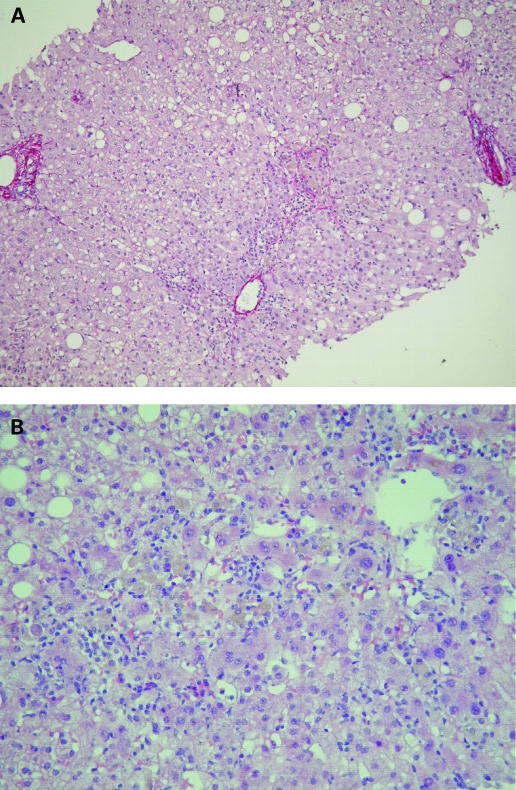

Abnormal liver tests were first observed in October 2007. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and serum aspartate aminotransferase were 8 and 3.5 times the upper limit of normal range, respectively (fig 1). Serum alkaline phosphatase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, and bilirubin were within normal ranges. Physical examination and hepatic ultrasonography were normal. Hepatitis B surface antigen and anti-hepatitis C virus antibodies were absent. Acute infection by hepatitis A virus, Epstein–Barr virus or cytomegalovirus was ruled out. In December 2007, antinuclear (1:320) and antismooth muscle antibodies (1:80) were present, while antimitochondrial and anti-liver-kidney-microcosm antibodies were negative. The serum IgG concentration was normal, as were ferritin, serum copper, caeruloplasmin, α1-antitrypsin concentrations and eosinophil count. Hepatotoxicity of glatiramer acetate was first suspected and therapy withdrawn on 12 January 2008, while other drugs were continued (fig 1). Liver biopsy was performed on 22 January and showed a predominance of centrolobular damage, characterised by areas of spotty and confluent necrosis, surrounded by some lymphocytes, eosinophils and macrophages (fig 2). There was no bridging necrosis. Sinusoidal pericentrolobular fibrosis was mild to moderate. Portal tracts showed sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes with scattered eosinophils and no spillover into the periportal parenchyma. These histological features were compatible with drug induced hepatitis. ß-1a interferon (30 μg/week) was started on 14 February as an alternative treatment for MS.

Figure 2.

Liver lesions. (A) Sirius red stain. Mild sinusoidal pericentrolobular fibrosis (black pointer) and normal portal tract (arrows). (B) Haematoxylin and eosin stain. Centrilobular damages: spotty (arrow) and confluent (black pointer) necrosis with lymphocytes, scattered eosinophils and macrophages with pigments.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Liver tests quickly improved after interruption of glatiramer acetate administration; they returned to normal by 17 April 2008 and have remained normal ever since (fig 1). Antinuclear antibodies were tested negative in January, February, April and June 2008. Anti-smooth muscle antibodies were negative or at low titres (⩽1:80) on the same dates. Serum IgG concentrations always remained within normal ranges.

DISCUSSION

Glatiramer acetate is reported to be well tolerated, and no cases of drug induced liver disease have been reported. Recently, glatiramer acetate was suggested to induce autoimmune disease. It is believed that glatiramer acetate induces T helper type 2 cells that cross-react with myelin basic protein2 and may enhance the production of autoantibodies. Moreover, the commercial formula of Copaxone contains mannitol, recently identified as an immunoactive hapten capable of provoking anaphylaxis.3 Therefore, it can be speculated that glatiramer acetate induces autoimmune side effects. Indeed, three recent case reports have described autoimmune diseases during glatiramer acetate therapy. One patient developed myasthenia gravis4 and another hyperthyroidism.5 Recently, a case of triggered autoimmune hepatitis was reported.3 In that case, the patient developed the first exacerbation of a previously unrecognised autoimmune hepatitis while on glatiramer acetate. That patient re-presented with elevated liver tests after initial normalisation while glatiramer acetate was discontinued for several months; liver tests returned to normal after budesonide and then mycophenolate mofetil were started. Unfortunately, the patient did not undergo liver biopsy.

It is likely that the elevated liver tests presented by our patient were related to glatiramer acetate induced hepatitis and not to triggered autoimmune hepatitis, for several reasons: (1) ALT values were normal before starting glatiramer acetate; (2) no other cause of liver disease was identified; (3) liver biopsy was consistent with a diagnosis of drug induced hepatitis but not with a diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis; (4) ALT returned to normal values after discontinuation of glatiramer acetate in spite of continuation of other treatments and the start of β-1a interferon, and remained normal during follow-up; and (5) initially identified antinuclear and anti-smooth muscle antibodies disappeared or were tested at low titres when glatiramer acetate was discontinued, and the serum IgG concentration was normal.

LEARNING POINTS

We believe that our patient developed glatiramer-acetate induced hepatitis.

Because MS is a serious condition, glatiramer acetate might become widely used.

The present case should serve as a warning that glatiramer acetate may cause acute liver disease.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schrempf W, Ziemssen T. Glatiramer acetate: mechanisms of action in multiple sclerosis. Autoimmun Rev 2007; 6: 469–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aharoni R, Teitelbaum D, Sela M, et al. Copolymer 1 induces T cells of the T helper type 2 that crossreact with myelin basic protein and suppress experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94: 10821–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann H, Csepregi A, Sailer M, et al. Glatiramer acetate induced acute exacerbation of autoimmune hepatitis in a patient with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2007; 254: 816–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frese A, Bethke F, Ludemann P, et al. Development of myasthenia gravis in a patient with multiple sclerosis during treatment with glatiramer acetate. J Neurol 2000; 247: 713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heesen C, Gbadamosi J, Schoser BG, et al. Autoimmune hyperthyroidism in multiple sclerosis under treatment with glatiramer acetate – a case report. Eur J Neurol 2001; 8: 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]