Abstract

A 48-year-old man was admitted under the care of urologists with acute renal failure and septicaemia secondary to pyelonephritis. Upon investigation, he was found to have renal stone disease secondary to a parathyroid adenoma. Further tests revealed high pituitary hormone and gastrin values, confirming the diagnosis of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1) and Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. Soon after this he experienced a series of renal complications due to his renal stone disease and multiple complications of his gastrinoma, including two gastrointestinal perforations and three episodes of significant upper gastrointestinal bleeds (two of which required laparotomies), and a full length oesophageal stricture—all within the span of 9 months. His complications were managed appropriately and the oesophageal stricture was treated with a full length metallic stent. He was discharged home in a reasonably good condition with normal swallowing, but unfortunately died of aspiration pneumonia 3 weeks later.

BACKGROUND

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1) is a relatively rare condition. Our patient developed a series of complications from various components of the syndrome in a rapid sequence and this did not allow us to investigate or treat him in a systematic or logical fashion. The limitations of therapeutic options proved to be a challenge for the entire multidisciplinary team. As the current literature describing the surgical management of gastrinomas in MEN 1 is far from exhaustive, this report aims to discuss and consolidate some of that information.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 49-year-old man with a 2 year history of declining renal function was admitted with acute renal failure and sepsis secondary to bilateral renal calculi. Hydronephrosis of his right kidney was treated with nephrostomy. Shortly after the procedure, he became hypotensive and vomited a large amount of coffee ground fluid. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed considerable thickening of the second and third parts of the duodenum and a possible nodule on the duodenum. Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy showed a large duodenal ulcer. He was treated with high dose proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

A diagnostic laparoscopy 1 week later confirmed thickening of the first part of the duodenum. Multiple laparoscopic and endoscopic biopsies revealed no evidence of malignancy. A feeding jejunostomy and drainage gastrostomy were inserted. Upon commencement of jejunal feeding, his general condition started to improve.

A right ureteric stent was inserted under radiological guidance and the nephrostomy tube was removed 3 days afterwards (fig 1). During this time he developed intermittent dysphagia and a barium swallow confirmed a tight stricture in the mid oesophagus at 25 cm (fig 2). His PPI dose was increased to the maximum and the stricture was endoscopically dilated to 16 mm.

Figure 1.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showing multiple calculi in both kidneys with the right ureteric stent in situ. Gas outlines the right pelvicalyceal system, possibly representing a pyonephrosis.

Figure 2.

Barium swallow showing a very tight stricture in the mid oesophagus. The extent of narrowing of the lumen allows barely any contrast to pass through.

In light of his ulcers, a diagnosis of MEN syndrome was considered as his serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) level was grossly elevated (875 pmol/l; normal 0.8–8.5 pmol/l), as was his corrected serum calcium (2.93 mmol/l; normal 2.12–2.65 mmol/l). Anterior pituitary hormone screens including follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinising hormone (LH), prolactin (PRL), growth hormone (GH), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), and adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) were consistently within normal ranges. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) value, male testosterone value, 9am cortisol value, thyroid function tests and blood glucose values were also unremarkable. A full gut hormone screen was carried out with the patient fasting and having stopped PPI treatment for more than a week as per laboratory protocol (to rule out iatrogenic increases in serum gastrin concentrations via PPI treatment); this revealed raised serum gastrin values (158 pmol/; normal <40 pmol/l), indicating the possibility of Zollinger–Ellison syndrome secondary to a gastrinoma. Subsequently, ultrasound scans confirmed a parathyroid adenoma in the right upper pole of the thyroid, for which he underwent subtotal parathyroidectomy. At the same time, endoscopic balloon dilatation of the oesophagus was done to 18 mm. He had three more dilatations of oesophagus on outpatient basis.

Four months after this, before a repeat attempt at oesophageal dilatation, the patient presented with signs of acute renal failure and loin pain, and became septic. This was initially attributed to an obstructed ureteric stent, but even after an emergency change of stent, the patient’s condition continued to deteriorate. After a few hours in the intensive care unit (ICU) he was found to be hypotensive, anuric and with a tender, distended abdomen. An urgent CT scan showed features of a gastrointestinal perforation.

At laparotomy, over 3 litres of murky bile stained fluid were found in the peritoneal cavity with a 1 cm diameter punched out perforation just beyond the duodenojejunal flexure. A 1.5 cm diameter nodule was also found in the anterior wall of the pylorus—this was suspected to be the gastrinoma responsible and was excised. A gastrostomy tube was then inserted. The pathology report of the biopsies showed the pyloric nodule to be a carcinoid tumour and not a gastrinoma, while the ulcer biopsy showed no active inflammation or malignancy.

One week later, his haemoglobin had dropped to 5.1 g/dl and had bleeding through his gastrostomy. He underwent an emergency laparotomy. A large 3 cm diameter posterior duodenal ulcer was found with a clot adherent to its base; it was also penetrating the duodenal wall, making Kocherisation impossible. There was no active bleeding and the base of the ulcer was under-run and packed. The duodenotomy was closed over a Foley catheter and a left paracolic drain and right infracolic drain were inserted.

Over the next 5 weeks, further deterioration of his renal function due to partial urinary obstruction led to the insertion of a left ureteric stent. His feeding jejunostomy also failed on multiple occasions and required unblocking. Jejunostomy feeding was hence temporarily stopped, and a central line was inserted to commence total parenteral nutrition, which lasted 2 weeks. It was around this time his blood cultures and cultures from laparotomy wound site, feeding jejunostomy and sputum were positive for yeast and methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). These were treated appropriately.

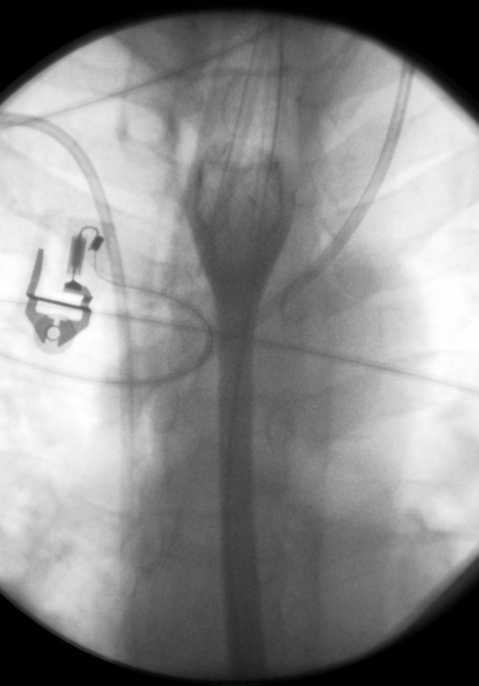

However, despite full dose PPI (160 mg of omeprazole per day) and octreotide while in the ICU, the patient showed signs of melaena and loss of fresh blood through his gastrostomy tube. Gastroscopy via the gastrostomy showed a large clot in the proximal duodenum, assumed to be the result of bleeding from around his previously identified ulcer. The clot was impossible to wash away but the mucosa at the base of the clot was injected with epinephrine (adrenaline). Concurrently, an 18 cm oesophageal stent was inserted under radiological guidance (fig 3).

Figure 3.

Water soluble contrast swallow showing satisfactory positioning and expansion of the stent. The contrast is able to pass freely through, with no evidence of leakage.

INVESTIGATIONS

CT abdomen

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy

Diagnostic laparoscopy with biopsy

Blood tests including pituitary hormone screen, thyroid function tests, blood glucose, parathyroid hormone, calcium, full gut hormone screen

Ultrasound of parathyroid glands

Blood cultures and cultures of sputum, laparotomy wound site and feeding jejunostomy site

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1)

Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (ZES)

TREATMENT

Full dose PPI (160 mg omeprazole) with octreotide

Feeding jejunostomy, drainage gastrostomy

Bilateral ureteric stents after initial nephrostomy

Subtotal parathyroidectomy with postoperative 1-α-calcidiol supplementation

Multiple laparotomies for duodenal ulcer perforations and bleeding

Repeated endoscopic balloon dilatations of the oesophagus

Injection of duodenal ulcer with adrenaline

Insertion of 18 cm oesophageal stent under radiological guidance

Continual psychological support for worsening depression and distress

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

After oesophageal stent insertion, swallowing function had vastly improved and oral feeding was recommenced. After a further 3 weeks of recovery, the decision to discharge was made. Unfortunately, the patient died 3 weeks after discharge, reportedly from aspiration pneumonia.

Towards the end of his treatment, the patient experienced gradually worsening depression and was even suicidal at one point, for which he had been receiving continual psychological support.

DISCUSSION

MEN 1 is an autosomal dominant inherited syndrome involving functioning hormone producing tumours in multiple organs: the parathyroid gland in 95% (with associated hypercalcaemia), pancreatic islets in 70% (usually gastrinomas or insulinomas), and anterior pituitary in 50% of cases. Adrenal and carcinoid tumours are also associated with this syndrome. The peak incidence of symptoms in women is during the third decade of life, and the fourth decade in men.1 More than half of MEN 1 patients have clinical involvement of more than one organ system, and approximately 20% have three affected endocrine glands. The three most common signs and symptoms in descending order are hypercalcaemia, nephrolithiasis, and peptic ulcer disease.2 Patients with MEN 1 have a decreased life expectancy, with a 50% probability of death by age 50. One half of the deaths are due to a malignant tumoural process or sequelae of the disease. Here, we focus on discussing the management of pancreaticoduodenal (PD) tumours, particularly gastrinoma and its consequences.

Gastrinomas are the most common functional PD endocrine tumours in MEN 1, and when associated with ZES, form the largest single cause of morbidity and mortality in MEN 1. Gastrinomas cause gastric acid hypersecretion and peptic ulcer disease that are best managed using PPIs. Whether routine surgical exploration should be performed to reduce malignant spread and eventually increase survival still remains controversial.3 Some evidence states that early and aggressive surgical treatment can influence the hormonal syndrome as well as address the malignant potential of both pancreatic and duodenal tumours. This includes distal pancreatectomy, enucleation of pancreatic head lesions, and duodenotomy with gastrinoma resection.4 New localisation techniques such as the selective arterial secretagogue injection (SASI) test and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS), together with endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and CT, have been shown to greatly enhance the accuracy of preoperative tumour localisation.5

Because PD neoplasms represent the principal disease specific lethality in MEN 1, potential oncologic benefits of PD resection must be weighed against operative morbidities, compromised pancreatic function, and quality of life (QoL). Many studies conclude that despite these perioperative risks, the moderate compromise in patient perceived QoL suggests that most patients accept and adapt to these tradeoffs for the potential of prolonged survival.6 Some studies consider MEN 1 tumours to be completely surgically curable and advocate that together with rapid intraoperative gastrin measurement (IGM), pancreaticoduodenectomy (for example, Whipple’s procedure) is superior to less radical surgical approaches in providing cure with limited morbidity in MEN 1 gastrinomas.7 However, such radical procedures should only be considered in cases of large, locally metastatic, advanced tumours and in the absence of hepatic metastases. Also, because gastrinomas are commonly multiple and originate mostly in the duodenum and develop lymph node metastases, the duodenum should be opened and all tumours and lymph nodes excised.8 Even then, one prospective study showed that in the 70% of patients with duodenal gastrinomas, even extensive duodenal exploration with removal of positive lymph nodes did not result in cures because 86% of tumours had metastasised to lymph nodes and 43% of patients had large numbers of tumours.9 Early and aggressive surgery for PD neuroendocrine tumours also prevents the development of liver metastasis, which is the most life threatening determinant.10

MEN 1 patients with ZES have a higher incidence of severe oesophageal disease, including the premalignant Barrett’s oesophagus. With our patient, oesophagitis complicated by severe stricture had a profound impact not only on nutrition status but also psychologically, as was evident by the patient’s eventual suicidal state of mind. It is crucial to diagnose ZES as early as possible so that gastric acid hypersecretion can be appropriately treated. This should invariably involve the use of PPIs, often twice daily. A study of three patients with ZES complicated by severe oesophagitis and intractable stricture recommended rapid institution of PPIs, parentally if necessary.11 However, another study reported severe oesophageal stricture and perforation despite maximum antisecretory control, and advocated instead that the best way to limit such complications would be complete excision of the underlying gastrinomas.12 As for oesophageal strictures, the best treatment is endoscopic balloon dilatation, which is accomplished either by bougienage, or by balloon dilatation; both of these methods are associated with improved success rates when done under fluoroscopic control.13 Strictures resistant to dilatation are managed palliatively by stent insertion. Comparative analyses suggest that the endoscopic placement of self expanding metal stents is effective, safe and preferable to conventional plastic prostheses.14

In conclusion, tumour resection, the absence of liver and lymph node metastases, and the presence of MEN 1 are related to a better survival rate. Radical surgery continues to have a central role in the therapeutic approach to pancreatic endocrine tumours.15 Because this syndrome is considered manageable but not curable, its components require continued surveillance in all patients. Patients should be assessed at least annually, and ongoing surveillance should follow the same pattern and use the same modalities as screening in unoperated patients. Prospective studies have detected biochemical evidence of neoplasia an average of 10 years before clinically evident disease, allowing for early surgical intervention. Genetically positive individuals should therefore undergo focused cancer surveillance for early detection.16 The useful modalities include biochemical hormone screening for evidence of parathyroid, pituitary and pancreatic disease, and pancreatic imaging with CT scan, SRS, and possibly EUS. The usual interval between follow-up assessments for an asymptomatic patient is 1 year.

LEARNING POINTS

Rapid sequence of complications did not allow for a full radiological work-up to localise his tumours and for subsequent treatment.

Full length tight oesophageal stricture along with gastrinoma presented unique management dilemma which could potentially have required removal of the entire foregut.

Frequency of upper gastrointestinal bleeds complications and their treatment by different consultants on different occasions highlights the importance of a dedicated multidisciplinary team with a good appreciation of the situation.

It highlights the potential limitations of European Working Time Directive (EWTD) culture.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brandi ML, Gagel RF, Angeli A, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and therapy of MEN type 1 and type 2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86: 5658–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doherty GM. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. J Surg Oncol 2005; 89: 143–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartsch DK, Langer P, Rothmund M. Surgical aspects of gastrinoma in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2007; 119: 602–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gauger PG, Thompson NW. Early surgical intervention and strategy in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 15: 213–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imamura M, Komoto I, Ota S. Changing treatment strategy for gastrinoma in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. World J Surg 2006; 30: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.You YN, Thompson GB, Young WF, Jr, et al. Pancreatoduodenal surgery in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: Operative outcomes, long-term function, and quality of life. Surgery 2007; 142: 829–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonelli F, Fratini G, Nesi G, et al. Pancreatectomy in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1-related gastrinomas and pancreatic endocrine neoplasias. Ann Surg 2006; 244: 61–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norton JA, Fang TD, Jensen RT. Surgery for gastrinoma and insulinoma in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2006; 4: 148–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacFarlane MP, Fraker DL, Alexander HR, et al. Prospective study of surgical resection of duodenal and pancreatic gastrinomas in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Surgery 1995; 118: 973–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartsch DK, Fendrich V, Langer P, et al. Outcome of duodenopancreatic resections in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Ann Surg 2005; 242: 757–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cadiot G, Helie C, Vallot T, et al. Stenosing esophagitis in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1994; 18: 1018–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bondeson AG, Bondeson L, Thompson NW. Stricture and perforation of the esophagus: overlooked threats in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. World J Surg 1990; 14: 361–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linda A. Diagnosis and Treatment Of Esophageal Strictures. Radiol Technol 1999; 70.4: 361(1). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosca F, Consoli A, Stracqualursi A, et al. Comparative retrospective study on the use of plastic prostheses and self-expanding metal stents in the palliative treatment of malignant strictures of the esophagus and cardia. Dis Esophagus 2003; 16: 119–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomassetti P, Campana D, Piscitelli L, et al. Endocrine pancreatic tumors: factors correlated with survival. Ann Oncol 2005; 16: 1806–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lairmore TC, Piersall LD, DeBenedetti MK, et al. Clinical genetic testing and early surgical intervention in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1). Ann Surg 2004; 239: 637–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]