Abstract

A 29-year-old male university student, with no prior history of trauma, presented with a 1 year history of clear fluid leaking intermittently from his left nostril. His past medical history included bilateral gynaecomastia since age 12, and recent low libido. β2-transferrin analysis of the nasal fluid confirmed a diagnosis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhoea. The serum prolactin was grossly elevated at 42 700 mU/l and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large parasellar/sellar mass. A diagnosis of invasive macroprolactinoma complicated by spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea was made. The patient was commenced on treatment with cabergoline, but while awaiting surgery to repair the CSF leak he developed streptococcus mitis and sanguis meningitis. He made an uncomplicated recovery with antibiotic treatment. Immediately following this episode, the CSF rhinorrhoea resolved spontaneously. Subsequently, a repeat MRI scan revealed dramatic involution of the pituitary mass and the serum prolactin had fallen to 604 mU/l.

BACKGROUND

The presentation of untreated macroprolactinoma with spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhoea is rare, with only 10 reported cases in the literature to date.1

Atraumatic CSF rhinorrhoea is an uncommon presentation in itself, and this case highlights the importance of careful clinical assessment and focused investigations, including anterior pituitary function testing and intracranial imaging, to establish the underlying cause.

CSF rhinorrhoea may be complicated by meningitis, and so early detection and referral for investigation and treatment is crucial for a favourable outcome.

Currently, there is no consensus as to the optimal timing of surgical repair for spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea in patients with invasive macroprolactinomas. While immediate repair reduces the risk of meningitis, it is well recognised that dopamine agonist therapy may be independently associated with the development of CSF rhinorrhoea as the tumour undergoes involution. Delayed repair may therefore reduce the number of surgical interventions that are required. In addition, resolution of CSF rhinorrhoea on dopamine agonist therapy while awaiting surgical treatment has been reported. This case highlights the difficulties facing the multidisciplinary team when deciding which approach to take.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 29-year-old male university student presented with a 1 year history of clear fluid leaking intermittently from his left nostril. He denied headaches or visual disturbance, and there was no history of trauma.

On specific questioning, he reported bilateral gynaecomastia since age 12 years, but had undergone normal puberty. Recently, he had noted a reduction in libido. There was no significant family history and he was on no regular medications.

Physical examination was unremarkable aside from the unilateral nasal discharge and mild bilateral gynaecomastia. There were no other stigmata of neurological or endocrine dysfunction.

INVESTIGATIONS

β2-transferrin analysis of the clear nasal fluid confirmed a diagnosis of CSF rhinorrhoea.

The serum prolactin concentration was grossly elevated at 42 700 mU/l (reference range 45–375 mU/l). Thyroid function tests were normal: free thyroxine (FT4) 13 pmol/l (reference range 11.5–22.7 pmol/l), thyrotropin (TSH) 3.5 mU/l (reference range 0.35–5.5 mU/l). His testosterone value was borderline low at 9.3 nmol/l (reference range 8–29 nmol/l), with a luteinising hormone (LH) of 1.9 IU/l (reference range 1.5–6.3 IU/l) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) of 1.5 IU/l (reference range 1.0–10.1 IU/l). Short synacthen testing was within normal limits: 0 mins cortisol 523 nmol/l, 30 mins cortisol 733 nmol/l (reference range >570 nmol/l), and his insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) was 22.5 nmol/l (reference range 9.5–45.0 nmol/l).

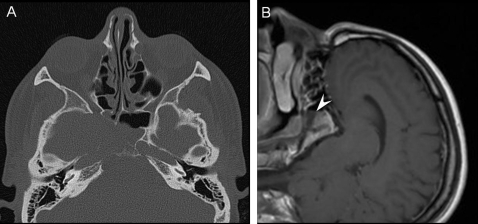

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) revealed a large invasive mass centred on the right cavernous sinus and sellar region, with evidence of associated erosion of the skull base, but no chiasmal compression (fig 1A and 2). Formal visual field assessment by perimetry was normal.

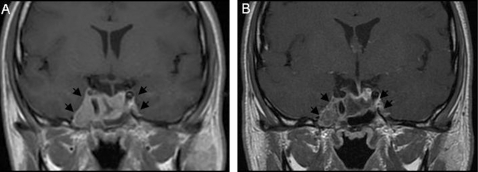

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): coronal T1 weighted images following contrast medium injection (gadolinium). (A) Homogenously enhancing mass (arrows) expanding the pituitary fossa and invading the right cavernous sinus. There is extension to the middle cranial fossa, skull base and sphenoid sinus. (B) Two months after commencing dopamine agonist therapy: significant reduction in mass (arrows) and enhancement.

Figure 2.

(A) Axial computed tomography at presentation: bone erosion of sellar floor, wall of sphenoid sinus and petrous apex. (B) Sagittal MRI post gadolinium at presentation (image rotated to demonstrate position of patient in scanner): tumour extension into sphenoid sinus and air–fluid level demonstrated (arrowhead).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Differential diagnosis of CSF rhinorrhoea:

Trauma (most within 3 months): skull base fractures in particular may present with CSF rhinorrhoea. In head trauma, prior series have reported a rate of CSF fistulae of 1–3%.2,3

Tumours (intracranial and extracranial) are the most common cause of non-traumatic CSF rhinorrhoea and, of these, pituitary tumours comprise the majority.4 Prolactinomas are the most frequently diagnosed functioning pituitary tumour, accounting for 40% of all pituitary adenomas.5

Iatrogenic (postoperatively).

Congenital defects of the skull base—for example, meningoceles, meningoencephaloceles.

Inflammation—for example, osteomyelitis of the skull.

TREATMENT

A diagnosis of invasive macroprolactinoma was made, and treatment was commenced with cabergoline 250 μg twice weekly, with surgery planned in 6–8 weeks to repair the leak. He was vaccinated against pneumococcus and advised of the potential symptoms of meningitis.

While awaiting surgery the patient elected to go on a short overseas trip, but unfortunately during this time he became unwell. He immediately attended a local hospital and was diagnosed with Streptococcus mitis and sanguis meningitis. He was treated with broad spectrum antibiotics.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient made a complete and uneventful recovery. The CSF rhinorrhoea spontaneously resolved immediately after the episode of meningitis.

A repeat pituitary MRI (2 months after starting cabergoline treatment) revealed marked shrinkage of the macroprolactinoma, with accompanying reduction in T1 signal intensity (fig 1B) in keeping with tumour involution. Consistent with this, the serum prolactin value had fallen to 604 mU/l.

The patient currently remains well on low dose cabergoline treatment, with no recurrence of his CSF rhinorrhoea. He continues under close surveillance with serial MRI and periodic pituitary function reassessment.

DISCUSSION

CSF rhinorrhoea is a clear nasal discharge of CSF that occurs when a fistula forms between the dura and the skull base. The diagnosis is confirmed by the detection (using immunofixation) of β2-transferrin in the nasal fluid. This is considered the definitive diagnostic test for identifying CSF, as opposed to the traditional method of glucose measurement, with superior sensitivity (≈100%) and specificity (≈95%).6

CSF rhinorrhoea may arise due to trauma and intracranial surgery, tumours, inflammation and congenital defects. It is a recognised complication of dopamine agonist treatment for invasive macroprolactinomas7. However, untreated prolactinomas presenting as spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea are extremely rare, with only 10 cases reported to date.1,8–10

A recent large study of patients with macroprolactinomas (n=114) showed an incidence of 8.7% for non-surgical CSF rhinorrhoea.10 The majority of these cases were secondary to dopamine agonist treatment (6.1%), with only three cases occurring spontaneously (2.6%). Our case further highlights spontaneous CSF leak as a possible presenting feature of invasive macroprolactinomas, and emphasises the importance of a focused history and further investigation with anterior pituitary function testing and MRI for anyone presenting with non-traumatic CSF rhinorrhoea.

Macroprolactinomas more commonly present with clinical features of hyperprolactinaemia, including loss of libido and potency in males, and galactorrhoea and menstrual dysfunction in females,5 but may also manifest as space occupying lesions, causing headaches, visual disturbances and hypopituitarism. Although not his presenting complaint, our patient retrospectively reported longstanding bilateral gynaecomastia (since age 12), which is a possible manifestation of hypogonadism/hyperprolactinaemia. Physiological pubertal gynaecomastia is normally short lived (typically 6 months or less), and in cases where it persists then further investigation is indicated. Our patient’s first endocrine assessment occurred at age 29, so, while it is tempting to potentially link the two conditions, there is a considerable time lapse between the two presentations, and it is not possible to determine the exact age of onset of the macroprolactinoma or the rate of growth of the tumour.

Various complications can develop in patients with CSF rhinorrhoea. These include meningitis, pneumocephalus and intracranial abscesses, which, if left untreated, have an associated mortality rate of 25–50%.11 Our patient developed meningitis while awaiting surgery. This is not an uncommon complication of CSF leakage, with a reported risk of 10% per annum.6 The use of prophylactic antibiotics in such patients is still controversial due to a lack of sufficiently large series,12,13 and although one meta-analysis showed some benefit,14 this was in the context of post-traumatic CSF rhinorrhoea.

Patient education regarding their condition and the risk of meningitis is therefore essential. Our patient was vaccinated against pneumococcus and advised of the possible symptoms of meningitis. This enabled prompt presentation and successful treatment of the patient in a different hospital.

Medical treatment, using dopaminergic agonists such as bromocriptine and cabergoline, is considered first line treatment for macroprolactinomas,15 unlike other pituitary tumours where surgery is preferred. Several studies have shown that cabergoline is more effective than bromocriptine in reducing tumour volume and decreasing prolactin secretion, and it is generally better tolerated by patients.16,17

Surgical resection is often reserved for patients who respond inadequately to, or are intolerant of, medical treatment. Where there is an associated CSF leak, surgery is recommended to repair the dural defect, thus reducing the risk of meningitis. This may be performed immediately or after initial tumour shrinkage.1,7 The latter has the potential advantage of reducing the chance of requiring a second reparative procedure, especially in those cases where there is marked tumour shrinkage in response to medical treatment.

In addition, spontaneous resolution of CSF rhinorrhoea in subjects receiving dopamine agonists while awaiting surgical treatment has also been reported.10 The mechanism underlying this is unclear, but may be attributable to a change in CSF pressure dynamics as the tumour shrinks under the influence of medical treatment. However, such an approach delays the time to primary repair, thereby leaving the patient at risk of developing meningitis. In our case this complication fortuitously caused resolution of the CSF rhinorrhoea, possibly due to local inflammation facilitating healing of the CSF fistula.

Further studies are required to define the role of preoperative dopamine agonist treatment, optimum timing of surgery, and the role for prophylactic antibiotics, in patients with macroprolactinomas who present with spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea.

LEARNING POINTS

CSF rhinorrhoea without an antecedent history of trauma is uncommon and, if suspected, should be promptly confirmed/excluded by β2-transferrin analysis.

Once confirmed, both the clinician and patient need to be alert to the possible complications, in particular meningitis, while awaiting definitive treatment.

Intracranial (mainly pituitary) tumours account for the majority of cases of non-traumatic CSF rhinorrhoea: thus, a focused history and examination should be performed and appropriate investigations (including pituitary function tests and intracranial imaging) instituted in a timely manner.

Macroprolactinomas, unlike other symptomatic pituitary tumours, are typically treated with primary medical therapy; however, in the case of CSF leak, surgery is indicated. The timing of the latter, and the risks/benefits of a trial of dopamine agonist treatment before surgical repair, must be discussed carefully with the patient.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Honegger JB, Psaras T, Petrick M, et al. Sponatneous cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea in untreated macroprolactinoma- an indication for primary surgical therapy. Zentralbl Neurochir 2006; 67: 149–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendizabal GR, Moreno BC, Flores CC. Cerebrospinal fluid fistula: frequency in head injuries. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 1992; 113: 423–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spetzler RF, Zabramski JM. Cerebrospinal fluid fistula. Contemp Neurosurg 1986; 8: 1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole IE, Keene M. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea in pituitary tumours. J R Soc Med 1980; 73: 244–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casaneuva FF, Molitch ME, Schlechte JA, et al. Guidelines of the Pituitary Society for the diagnosis and management of prolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol 2006; 65: 265–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones NS, Becker DG. Advances in the management of CSF leaks. BMJ 2001; 322: 122–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leong KS, Foy PM, Swift AC, et al. CSF rhinorrhoea following treatment with dopamine agonists for massive invasive prolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol 2000; 52: 43–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obana WG, Hodes JE, Weinstein PR, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea in patients with untreated pituitary adenoma: report of two cases. Surg Neurol 1990; 33: 336–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanel RA, Prevedello DM, Correa A, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid fistula as the presenting manifestation of pituitary adenoma: case report with four year follow up. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2001; 59: 263–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suliman SG, Gurlek A, Byrne JV, et al. Nonsurgical cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea in invasive macroprolactinoma: incidence, radiological, and clinicopathological features. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92: 3829–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aarabi B, Leibrock LG. Neurosurgical approaches to cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea. Ear Nose Throat J 1992; 71: 300–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi D, Spann R. Traumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage: risk factors and the use of prophylactic antibiotics. Br J Neurosurg 1996; 10: 571–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moralee SJ. Should prophylactic antibiotics be used in the management of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea following endoscopic sinus surgery? A review of the literature. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 1995; 20: 100–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brodie HA. Prophylactic antibiotics for posttraumatic cerebrospinal fluid fistulae. A metaanalysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997; 123: 749–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nomikos P, Buchfelder M, Fahlbusch R. Current management of prolactinomas. J Neurooncol 2001; 54: 139–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webster J, Piscitelli G, Polli A, et al. A comparison of cabergoline and bromocriptine in the treatment of hyperprolactinemic amenorrhea. Cabergoline Comparative Study Group. N Engl J Med 1994; 6;331: 904–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colao A, Di Sarno A, Sarnacchiaro F, et al. Prolactinomas resistant to standard dopamine agonists respond to chronic cabergoline treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997; 82: 876–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]