Abstract

Patients with Turner syndrome (TS) are at risk for aortic dissection, but the clinical profile for those at risk is not well described. In addition to reporting two new cases, we performed an electronic search to identify all reported cases of aortic dissection associated with TS. In total, 85 cases of aortic dissection in TS were reported between 1961 and 2006. Dissection occurred at a young age, 30.7 (range 4–64) years, which is significantly earlier than its occurrence in the general female population (68 years). Importantly, in 11% of the cases, neither hypertension nor congenital heart disease were identified, suggesting that TS alone is an independent risk factor for aortic dissection; however, the cases where no risk factors were identified were very poorly documented. A TS aortic dissection registry has been established to determine the natural history and risk factors better (http://www.turnersyndrome.org/).

BACKGROUND

Aortic dissection occurs in individuals with disorders of connective tissue, including those caused by fibrillin mutations (Marfan syndrome), collagen mutations (Ehlers–Danlos syndrome), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β receptor mutations (Loeys–Dietz syndrome), and in those in which a connective tissue disorder is postulated but not proven, such as bicuspid aortic valve syndrome and Turner syndrome (TS). In Marfan syndrome, guidelines for monitoring of aortic root dimension and indications for surgical intervention to prevent dissection are established, but for those with less common causes, treatment guidelines are lacking. In TS in particular, the medical community has been slow to recognise the evidence for the significant risk of catastrophic aortic dissection. This is partly because aortic dissection is relatively rare in TS (1.4%).1 Perhaps more importantly, the little information available is diffuse and disorganised, consisting of clinic based studies,2 unverified data obtained from questionnaires,3 and sporadic cases reports that describe only one or two cases of aortic dissection. A comprehensive review describing all of the reported cases of aortic dissection in TS has not been published. We describe two previously unreported cases of dissection occurring in young women with TS, review all of the published cases of aortic dissection occurring in TS, and announce the establishment of the International Turner Syndrome Aortic Dissection Registry. In this review, particular attention was paid to cases in which only the diagnosis of TS was present and other predisposing risk factors, such as congenital heart disease (CHD) or systemic hypertension, were expressly absent.

CASE PRESENTATION

An 18-year-old woman with TS (45,X) presented to an emergency department with full cardiac arrest. She had a 4 day history of chest pain. The patient died soon after presentation, and an autopsy revealed type A aortic dissection.

The patient had been treated with a tumour necrosis factor (TNF) blocker (infliximab) for Crohn disease for 8 years. TS was diagnosed at the age of 14 years after an evaluation for short stature and delay of pubertal development. An echocardiogram performed at the time of the initial TS evaluation found a non-obstructive, functionally bicuspid aortic valve and trace aortic valve insufficiency. The patient had a mildly dilated ascending aorta of 28.5 mm (Z score = 3.1). There was no evidence of coarctation. At 17 years of age, another echocardiogram reported ascending aorta diameters of 28 and 32 mm (Z score = 2.2 to 3.8). Blood pressure was normal (102/60 mm Hg). Two days before death, the patient reported chest and upper back pain. Blood pressure was 108/84 mm Hg. The patient had abdominal pain with palpation and an audible abdominal bruit. Her paediatric cardiologist did not think there was a cardiac basis for her pain. She was told she had gastritis and started on antacid treatment.

A 29-year-old woman with TS (45, X) presented to the emergency department with a 2 day history of shortness of breath and intermittent chest pain. Shortly after presentation, she became unresponsive, apnoeic and pulseless. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was started, but the patient died. Before the arrest, pallor and rales had been noted and thrombolytic treatment started for presumed pulmonary embolus. Type A aortic dissection was found at autopsy. In addition to TS, the patient had a bicuspid aortic valve, hypertension (treated with atenolol), hypothyroidism, and a history of bipolar disorder that was treated with lithium and an antidepressant.

The patient’s most recent echocardiogram 15 months before the dissection showed a mildly thickened aortic valve without stenosis or insufficiency, mild mitral valve thickening and normal systolic function. The aortic root diameter measured 22 mm (z =−0.5). Despite β-blocker treatment, the most recent blood pressure measurements showed systemic hypertension (142/82 mm Hg).

INVESTIGATIONS

We performed an electronic search from 1961 to 2006 designed to capture all reported cases of aortic dissection in girls and women with TS (key words: Turner syndrome, aortic dissection, aortic dilatation). Cases were excluded if aortic dissection in Turner syndrome was not explicit. However, cases were still included in the review even if the method of diagnosing heart disease or measuring blood pressure were not precisely stated. In total, 23 articles, five short commentaries, four letters to the editor, and eight abstracts were ultimately included in this report. Cases were cross-referenced in order to avoid duplication of cases. Age at dissection, location of dissection, mention of known risk factors (that is, CHD and/or hypertension), treatment and outcome were recorded.

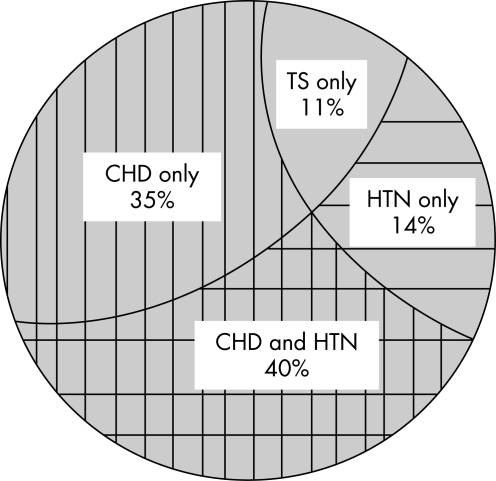

In total, 88 cases were reported between 1961–2006. Of these, 85 cases were included in this review; three cases were excluded because they lacked identifying information. The mean age at time of dissection was 30.7 (range 4–64) years. Over half the patients were aged <30 years. A karyotype was reported in 58% (49/85). A 45X karyotype was present in 80% (39/49) of the cases where karyotype was reported. In 10 cases, various forms of mosaicism were described: 45X/46XX (1 patient), 45X/46XY (3), 45X/46X,r(X) (4), 45X/46X+mar4 (1) and not specified (1). The location of the aortic dissection was provided in 71 of the 85 cases. Over half (55%; 47/85) of the dissections occurred in the proximal aorta and 23% (20/85) in the distal aorta. In three cases, both the ascending and descending aortas were involved. CHD was reported in 69% (51/74) cases that were evaluated for CHD. Of these 51 cases, 47% (24/51) had reported coarctation of the aorta, 27% (14/51) bicuspid aortic valve (BAV), and 18% (9/51) both BAV and a coarctation. Of the 65 cases in which blood pressure and CHD were both explicitly assessed (fig 1), 54% (35/65) had hypertension, although in most of the cases the blood pressure values were not reported. In addition, in this group, for which both risk factors were assessed, 75% (49/65) had associated CHD. The online supplemental tables (available at http://jmg.bmj.com/supplemental) report the cases in which CHD occurred in isolation (table S14–20), in which hypertension was the only risk factor described (table S221–24), and in which both CHD and hypertension were present (table S325–39).

Figure 1.

Venn diagram of 65 people with Turner syndrome (TS) who had aortic dissection where signs of congenital heart disease (CHD) or systemic hypertension (HTN) were explicitly considered.

Assisted reproductive technology (ART) resulted in pregnancy complicated by aortic dissection in six instances.40–44 In a seventh case death occurred 1 year after ART.40 Maternal death was reported in 86% (6/7) of these cases.

No risk factors were reported in 21% (18/85) overall (table 1). Importantly, most case reports that listed no risk factors did not explicitly exclude them. However, in 11% (7/65), the presence (or absence) of CHD and hypertension was specifically investigated and not identified (table 1, fig 1). The age range of these seven women was between 20 and 53 (mean 36) years. In one case, aortic dissection occurred during the third trimester in a pregnant women who had ART.40 Four of six cases reported a proximal aortic dissection and in one case the dissection was both proximal and distal. Although all seven cases excluded hypertension and CHD, only two cases reported the actual blood pressure values, and the method used to exclude CHD was described in only three cases.

Table 1.

Patients with no hypertension or congenital heart disease

| Patient no | Age, years | Heart disease | Hyper- tension | Karyotype | Outcome | Pathology | Location of dissection | Other information | CHD exclusion criteria | Reference |

| 1 | 20 | No | No | 45,X | Deceased | CMN | Proximal | NR | Rubin55 | |

| 2 | 27 | No | No | NR | Alive | NR | Very distal | Abdominal aorta | Echo, angiography, MRI | Bartlema56 |

| 3 | 30 | No | No | 45X/46X + ring | Deceased | CMN | Proximal | Autopsy | Price57 | |

| 4 | 39 | No | No | 45,X | Deceased | NR | Proximal and distal | Autopsy | Price57 | |

| 5 | 51 | No | No | 45,X/46 X, r(X) | Alive | NR | Proximal | NR | Gravholt1 | |

| 6 | 53 | No | No | 45,X | Deceased | NR | Proximal | NR | Gravholt1 | |

| 7 | NR | No | No | NR | Deceased | NR | NR | Dissection during third trimester of pregnancy | NR | Nagel40 |

| 8 | 9.5 | NR | No | 45,X | Alive | NR | Site of surgical repair? | NR | Sybert2 | |

| 9 | 10 | No | NR | NR | Deceased | NR | Proximal | NR | Hata58 | |

| 10 | 18 | NR | NR | 45 X/46XY | Deceased | CMN | Proximal | NR | Gravholt1 | |

| 11 | 28 | NR | No | 45,X | Deceased | NR | Distal | NR | Gravholt1 | |

| 12 | 29 | No | NR | 45,X/46X,r(X) | Deceased | NR | NR | Price59 | ||

| 13 | 30 | NR | NR | NR | Alive | NR | Proximal | Surgical repair | NR | Hirose60 |

| 14 | 34 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Dissection of aortic aneurysm | NR | Chlumsky61 |

| 15 | 38 | NR | NR | 45,X | Alive | NR | Proximal | Surgical repair | NR | Meunier62 |

| 16 | NR | NR | NR | Alive | NR | Distal | NR | Clement63 | ||

| 17 | 39 | No | NR | 45,X | Deceased | NR | NR | NR | Price59 | |

| 18 | 49 | No | NR | NR | Deceased | NR | NR | NR | Hata58 | |

| 19 | 61 | NR | No | 45,X | Deceased | NR | NR | NR | Gravholt1 |

CHD, congenital heart disease; CMN, cystic medial necrosis; NR, not reported; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

The symptoms most commonly reported before dissection were chest pain, diaphoresis and tachycardia. In the majority of cases, surgical and/or medical treatments were tried. In all 22 instances in which the pathology of the aorta was reported, it was found to be cystic medial necrosis. In 83 of the cases an outcome was reported, with death occurring in 48/83 cases (58%).

DISCUSSION

In this review, 85 cases of dissection of the aorta were identified in women with TS. These data demonstrate that in most cases a known risk factor for dissection is present, either systemic hypertension, a predisposing cardiac malformation or both. Of significant concern are the reports of aortic dissection occurring in seven women during ART. In one study of pregnancy in women with coarctation, the only death was due to aortic dissection in a woman with TS.42 Although there are no data regarding how commonly ART is undertaken by TS women, the fact that most women (86%) in our review died suggests that pregnancy is a major risk factor in TS. Dissection of the aorta occurs in TS at a remarkably young age (mean 31 years). In contrast, the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection found that the mean age of dissection in non-TS women is 68 years.45 Furthermore, aortic dissection is predominantly a male disease (male:female ratio 3.2:1, age adjusted mortality rate).46 The reasons that aortic dissection occurs in this unique group of young women deserves further attention.

Bicuspid aortic valve, aortic coarctation and systemic hypertension are established risk factors for aortic dissection in the general population47 and they often occur in TS. Approximately 25–30% of women with TS have a cardiovascular malformation and, of those affected, most have aortic disease.48,49 Systemic hypertension has been reported to occur in 50% of women with TS.49 Thus, in TS there appears to be a confluence of established risk factors leading to aortic dissection. In support of this theory, we found that 89% of cases of aortic dissection had at least one established risk factor.

On the other hand, we and others3 have found no identifiable risk factor in approximately 11% of cases. This could be because the known associations were not adequately assessed. Indeed, the cases we reviewed that carried the claim of no risk factors were, for the most part, very poorly documented. However, others have suggested that TS involves a primary disorder of the composition of the aortic wall that creates vulnerability by lowering the threshold for dilation, dissection and rupture. The data in table 1 showing that some patients had neither of the established risk factors suggest that TS alone may be predisposing to aortic dissection. Histological evidence of cystic medial necrosis in aortic tissue taken from patients with bicuspid aortic valve, Marfan syndrome and TS suggests a common aetiology despite genetically diverse backgrounds. In this regard, Ostberg et al50 recently documented intimal–medial thickening and vessel dilation diffusely in the vasculature, including the aorta in women with TS, even in the absence of CHD. Interestingly, similar pathological findings are typically present in other aortopathies, including Marfan syndrome. The presence of vessel wall thickening in these diseases is evidence against the conventional view that increased wall stress produced by high blood pressure, jets from stenotic aortic valves, or abnormal proteins of the aortic tissue produce thinning of the vessel wall, which leads to dilation and eventual aortic rupture. Other observations51 suggest that a disorder of growth factor signal transduction ultimately weakens the aortic wall. These studies report a variety of aortic diseases in which there is a constellation of findings, including vessel wall thickening, upregulation of TGF-β signalling and proliferation of matrix proteins. In TS the observation of aortic wall thickening suggests that it may also be a disorder associated with upregulation of TGF-β signalling.

Knowledge of the natural history and clinical findings of Marfan syndrome has been used to make judgments regarding proper monitoring and treatment of TS individuals with aortic enlargement. However, it is clear from this review that very little is known about the prodrome of aortic dissection in this population. For example, it is completely unknown whether aortic dissection is preceded by progressive dilation of the aortic root as it is in Marfan syndrome. Indeed, in both of the new cases presented in this report, the most recent aortic Z score determined by echocardiography was <4, a value that most cardiologists would not consider to be at risk for imminent dissection. We conclude from our review that there is a profound lack of a reliable medical profile for those with TS who have dissected. Accordingly, it is appropriate that the position of the American Academy of Pediatrics on the monitoring and management of aortic disease in TS is open ended, recommending that medical monitoring should be determined by the primary cardiologist or care provider.52 The Turner Syndrome NIH Consensus Study Group recently published more focused guidelines,53 but also with little evidence to support their recommendations. These guidelines recommend a baseline echocardiogram to assess for CHD and frequent blood pressure screening. For those who have no cardiovascular disease or hypertension, the recommendations include reassessment of the cardiovascular system with a cardiac MRI when sedation is not necessary and repeating either an echocardiogram or MRI every 5–10 years. However, it is unclear if surveillance studies would be able to detect progressive aortic dilatation or imminent dissection. To gain a better understanding of the natural history of aortic dissection in women with TS, we have established an International Turner Syndrome Aortic Dissection Registry (ITSADR, http://www.turnersyndrome.org/).54 Its goal is to identify all girls and women with TS and aortic dissection, to profile their risk factors and to more precisely define the appearance and progression of aortic disease leading to dissection.

All doctors who care for women with TS should be aware of their risk for aortic dissection. The apparent risk during pregnancy for those receiving ART must be recognised and early education of TS women contemplating pregnancy is mandatory. We found that in many of the reported cases and in the two cases presented here, the symptoms developed insidiously over the course of hours to days. A preliminary review of the data of the ITSADR suggests that the signs and symptoms that may herald an aortic dissection include apparently minor complaints such as abdominal pain, “heartburn”, back or shoulder pain, or a change in phonation (due to traction on the recurrent laryngeal nerve). Symptoms that persist should always be taken seriously and warrant complete investigation including transoesophageal echocardiography, chest CT or cardiac MRI.

LEARNING POINTS

Aortic dissection in Turner syndrome has high mortality.

Turner syndrome is a risk factor for aortic dissection.

Aortic dissection in Turner syndrome is currently poorly characterised.

Acknowledgments

This article has been adapted with permission from Carlson M, Silberbach M. Dissection of the aorta in Turner syndrome: two cases and review of 85 cases in the literature. J Med Genet 2007; 44: 745–9 .

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gravholt CH, Landin–Wilhelmsen K, Stochholm K, et al. Clinical and epidemiological description of aortic dissection in Turner’s syndrome. Cardiol Young 2006; 16: 430–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sybert VP. Cardiovascular malformations and complications in Turner syndrome. Pediatrics 1998; 101: E11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin AE, Lippe B, Rosenfeld RG. Further delineation of aortic dilation, dissection and rupture in patients with Turner syndrome. Pediatrics 1998; 102: e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asch AJ. Turner’s syndrome occurring with Horner’s syndrome. Seen with coarctation of the aorta and aortic aneurysm. Am J Dis Child 1979; 133: 827–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buheitel G, Singer H, Hofbeck M. [Aortic aneurysms in Ullrich-Turner syndrome]. Klinische Padiatrie 1996; 208: 42–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerin FGD, de Saint-Maur P, Akoun J, et al. Dissection aortique et syndrome de Turner. Coeur 1974; 5: 771–5 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imamura M, Aoki H, Eya K, et al. Balloon angioplasty before Wheat’s operation in a patient with Turner’s syndrome. Cardiovasc Surg 1995; 3: 70–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kusaba E, Imada T, Iwakuma A, et al. [Aortic aneurysm complicated with coarctation of the aorta and Turner syndrome]. Kyobu Geka 1995; 48: 1115–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vesin S, Chudanova V. [Aortic aneurysm in Turner’s syndrome]. Cesk Radiol 1989; 43: 226–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allemann J, Muller G, Legat M. [Rare variant of a Turner-Ullrich syndrome]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1982; 112: 1249–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohuchi H, Takasugi H, Ohashi H, et al. Stratification of pediatric heart failure on the basis of neurohormonal and cardiac autonomic nervous activities in patients with congenital heart disease. Circulation 2003; 108: 2368–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards WD, Leaf DS, Edwards JE. Dissecting aortic aneurysm associated with congenital bicuspid aortic valve. Circulation 1978; 57: 1022–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg SM, Pizzarello RA, Goldman MA, et al. Aortic dilatation resulting in chronic aortic regurgitation and complicated by aortic dissection in a patient with Turner’s syndrome. Clin Cardiol 1984; 7: 233–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiroma K, Ebine K, Tamura S, et al. A case of Turner’s syndrome associated with partial anomalous pulmonary venous return complicated by dissecting aortic aneurysm and aortic regurgitation. J Cardiovasc Surg 1997; 38: 257–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kostich ND, Opitz JM. Ullrich-Turner syndrome associated with cystic medial necrosis of the aorta and great vessels: case report and review of the literature. Am J Med 1965; 38: 943–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Apostolopoulos T, Kyriakidis M, et al. Endarteritis of the aortic arch in Turner’s syndrome with cystic degeneration of the aorta. Int J Cardiol 1992; 35: 417–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slater DN, Grundman MJ, Mitchell L. Turner’s syndrome associated with bicuspid aortic stenosis and dissecting aortic aneurysm. Postgrad Med J 1982; 58: 436–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin MM, Beekman RH, Rocchini AP, et al. Aortic aneurysms after subclavian angioplasty repair of coarctation of the aorta. Am J Cardiol 1988; 61: 951–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravelo HR, Stephenson LW, Friedman S, et al. Coarctation resection in children with Turner’s syndrome: a note of caution. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1980; 80: 427–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oohara K, Yamazaki T, Sakaguchi K, et al. Acute aortic dissection, aortic insufficiency and a single coronary artery in a patient with Turner’s syndrome. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1995; 36: 273–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lippe BM, Kogut MD. Aortic rupture in gonadal dysgenesis. J Pediatr 1972; 80: 895–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kido G, Miyagi A, Shibuya T, et al. [Turner’s syndrome with pituitary hyperplasia: a case report]. No Shinkei Geka 1994; 22): 333–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akimoto N, Shimizu T, Ishikawa M, et al. The surgical treatment of aortic dissection in a patient with Turner’s syndrome: report of a case. Surg Today 1994; 24: 929–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salgado CR. [Turner’s syndrome. Report of a case associated with dissecting aneurysm of the aorta. Review of the literature]. Rev Fac Cienc Med Cordoba 1961; 19: 193–204 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ota Y, Tsunemoto M, Shimada M, et al. [Aortic dissection associated with Turner’s syndrome]. Kyobu Geka 1992; 45: 411–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strader WJ, Wachtel HL, Lundberg GD. Hypertension and aortic rupture in gonadal dysgenesis. J Pediatr 1971; 79: 473–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fejzic Z, van Oort A. Fatal dissection of the descending aorta after implantation of a stent in a 19-year-old female with Turner’s syndrome. Cardiol Young 2005; 15: 529–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Youker JE, Roe BB. Aneurysm of the aortic sinuses and ascending aorta in Turner’s syndrome. Am J Cardiol 1969; 23: 89–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cecchi F, Samoun M, Santoro G, et al. [Chronic dissecting aortic aneurysm and Turner’s syndrome. Apropos of a case]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 1992; 85: 1043–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bordeleau L, Cwinn A, Turek M, et al. Aortic dissection and Turner’s syndrome: case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med 1998; 16: 593–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramaniam PN. Turner’s syndrome and cardiovascular anomalies: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci 1989; 297: 260–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anabtawi IN, Ellison RG, Yeh TJ, et al. Dissecting aneurysm of aorta associated with Turner’s syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1964; 47: 750–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lie JT. Aortic dissection in Turner’s syndrome. Am Heart J 1982; 103: 1077–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollak H, Veit F, Enenkel W. [Presumed “successful” fibrinolysis in unrecognized acute aortic dissection]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1992; 117: 368–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badmanaban B, Mole D, Sarsam MA. Descending aortic dissection post coarctation repair in a patient with Turner’s syndrome. J Card Surg 2003; 18: 153–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gopal AS, Arora NS, Vardanian S, et al. Utility of transesophageal echocardiography for the characterization of cardiovascular anomalies associated with Turner’s syndrome. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2001; 14: 60–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hochberg Z. Sudden death in Turner’s syndrome. Harefuh 1995; 129: 285–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeresaty RM, Basu SK, Franco J. Dissecting aneurysm of the aorta in Turner’s syndrome. JAMA 1972; 222: 574–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller JM HE, Puga UC, Torres GS. Sindrome de Turner y aneurisma disecante de la aorta. Arch Inst Cardiol Mex 1974; 44: 771–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagel TC, Tesch LG. ART and high risk patients! Fertil Steril 1997; 68: 748–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Bryman I, Hanson C, et al. Spontaneous pregnancies in a Turner syndrome woman with Y-chromosome mosaicism. J Assist Reprod Genet 2004; 21: 229–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beauchesne LM, Connolly HM, Ammash NM, et al. Coarctation of the aorta: outcome of pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 38: 1728–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garvey P, Elovitz M, Landsberger EJ. Aortic dissection and myocardial infarction in a pregnant patient with Turner syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 1998; 91: 864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weytjens C, Bove T, Van Der Niepen P. Aortic dissection and Turner’s syndrome. J Cardiovasc Surg 2000; 41: 295–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nienaber CA, Fattori R, Mehta RH, Richartz BM, Evangelista A, Petzsch M, Cooper JV, Januzzi JL, Ince H, Sechtem U, Bossone E, Fang J, Smith DE, Isselbacher EM, Pape LA, Eagle KA, on Behalf of the International Registry of Acute Aortic D Gender-related differences in acute aortic dissection. Circulation 2004; 109: 3014–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gillum RF. Epidemiology of aortic aneurysm in the United States. J Clin Epidemiol 1995; 48: 1289–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Homme JL, Aubry MC, Edwards WD, et al. Surgical pathology of the ascending aorta: a clinicopathologic study of 513 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30: 1159–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gotzsche CO, Krag-Olsen B, Nielsen J, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular malformations and association with karyotypes in Turner’s syndrome. Arch Dis Child 1994; 71: 433–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elsheikh M, Casadei B, Conway GS, et al. Hypertension is a major risk factor for aortic root dilatation in women with Turner’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001; 54: 69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ostberg JE, Donald AE, Halcox JP, et al. Vasculopathy in Turner syndrome: arterial dilatation and intimal thickening without endothelial dysfunction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90: 5161–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinson PN, Arteaga-Solis E, Baldock C, et al. The molecular genetics of Marfan syndrome and related disorders. J Med Genet 2006; 43: 769–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frias JL, Davenport ML. Health supervision for children with Turner syndrome. Pediatrics 2003; 111: 692–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bondy CA. Care of girls and women with turner syndrome: a guideline of the turner syndrome study group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92: 10–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.International Turner Syndrome Dissection Registry. http://www.tssus.org/readweb.asp?wid=3092. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rubin K. Aortic dissection and rupture in Turner syndrome. J Pediatr 1993; 122: 670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bartlema KA, Hogervorst M, Akkersdijk GJ, et al. Isolated abdominal aortic dissection in a patient with Turner’s syndrome. Surgery 1995; 117: 116–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Price WH, Wilson J. Dissection of the aorta in Turner’s syndrome. J Med Genet 1983; 2: 61–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hata J. Ultrastructural and histochemical studies on aortic dissection aneurysm. Myok Kangaku 1986; 26: 493–8 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Price WH, Clayton JF, Collyer S, et al. Mortality ratios, life expectancy and causes of death in patients with Turner’s syndrome. J Epidemiol Community Health 1986; 40: 97–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hirose H, Amano A, Takahashi A, et al. Ruptured aortic dissecting aneurysm in Turner’s syndrome: a case report and review of literature. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000; 6: 275–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chlumsky J, Kolbel F, Buresova M, et al. [A dissecting aortic aneurysm in a female patient with Turner syndrome]. Vnitr Lek 2000; 46: 34–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meunier JP, Jazayeri S, David M. Acute type A aortic dissection in an adult patient with Turner’s syndrome. Heart 2001; 86: 546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clement CI, Brereton J, Clifton–Bligh P. Aortic dissection in Turner syndrome. Med J Aust 2004; 180: 584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]