Abstract

Substance abuse and addiction are highly prevalent in HIV-infected individuals. Substance abuse is an important comorbidity that affects the delivery and outcomes of HIV medical management. In this paper I will review data examining the associations between substance abuse and HIV treatment and potential strategies to improve outcomes in this population that warrant further investigation. Current - but not past - substance abuse adversely affects engagement in care, acceptance of antiretroviral therapy, adherence with therapy, and long-term persistence in care. Substance abuse treatment appears to facilitate engagement in HIV care, and access to evidence-based treatment for substance abuse is central to addressing the HIV epidemic. Strategies that show promise for HIV-infected substance abusers include integrated treatment models, directly observed therapy, and incentive-based interventions.

Introduction

Injection drug use continues to be an important mode of HIV transmission worldwide and is the primary mode of transmission in Eastern Europe, Russia, and areas of Southeast Asia (Mathers et al., 2008). Substance abuse and addiction are highly prevalent in HIV-infected populations, including those where transmission of HIV is primarily sexual. Substance abuse is an important comorbidity that affects the delivery and outcomes of HIV medical management. In this paper, I will review the interaction between substance abuse and HIV treatment outcomes and discuss strategic approaches to treating this population.

Barriers to care in HIV-infected substance abusers

Substance abuse is a well documented obstacle to care among HIV-infected individuals that exerts deleterious effects at multiple levels. The neglect of social, occupational, and personal obligations is a central component of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition (DSM IV) definition of substance addiction (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The addict’s outlook is characteristically myopic, focused on slaking the short-term demands of addiction with increasing neglect of longer-term interests, including maintaining health. Substance abuse and addiction commonly co-occur with other factors that pose added barriers to optimal HIV treatment (box). Psychiatric comorbidity, including depression, is common among HIV-infected substance abusers (Treisman et al., 2001) and has been shown to be independently associated with HIV disease progression (Golub et al., 2003;Ickovics et al., 2001).

Box1.

Box. Common co-occurring conditions in HIV-infected substance abusers that adversely affect adherence and treatment outcomes

|

|

Substance abusers commonly confront stigma in their interactions with medical providers, and similarly, they are often mistrustful of the medical establishment. In a survey of primary care clinicians, 55% of those surveyed expressed negative attitudes about treating drug users while only 28% described themselves as being comfortable having drug users in their practices (Gerbert et al., 1991). Altice and colleagues found considerable mistrust of the medical establishment in a survey of 205 incarcerated drug users. 47% and 53% of those surveyed expressed agreements with the statements “HIV was made in a laboratory” and “there is a cure for AIDS, but the government is keeping it from me”, respectively (Altice et al., 2001). Patient-provider trust and communication has been found to be an important factor in healthcare disparities (Cooper, 2009).

Stages in the HIV care continuum: substance abuse-related barriers

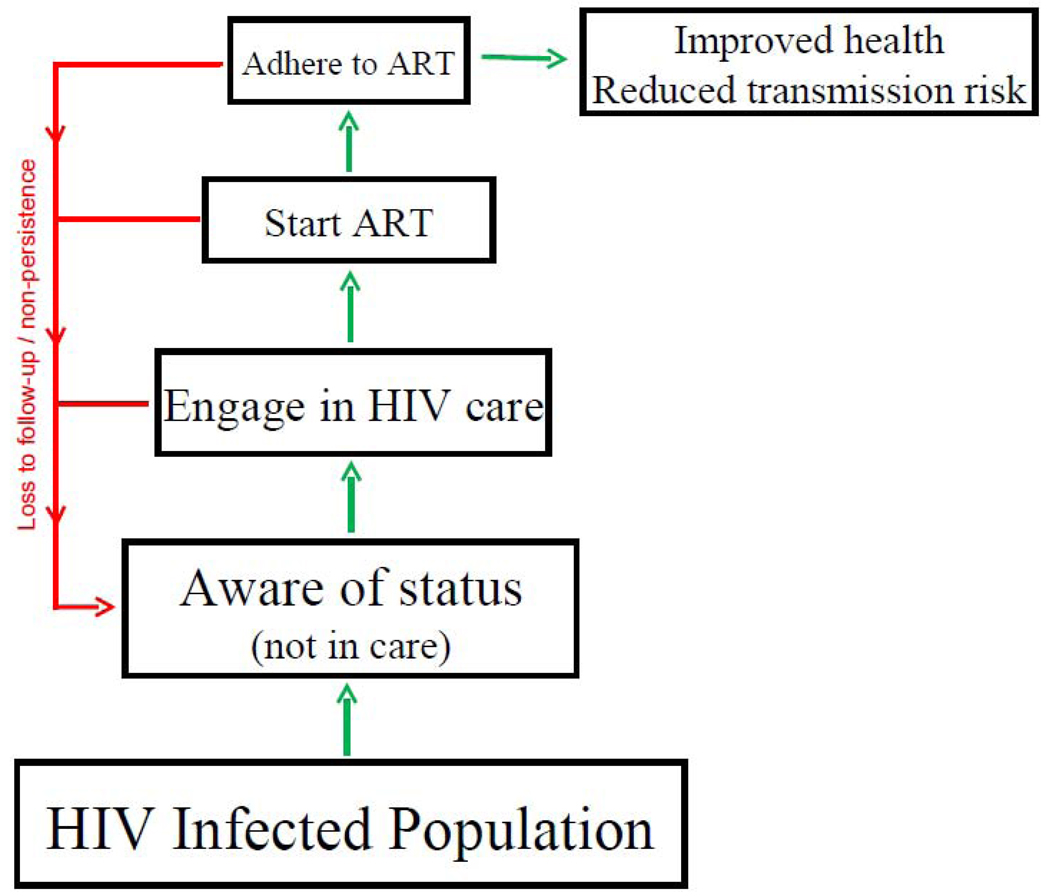

Engagement in care and successful treatment of HIV entails progression through several steps (Figure). Movement through these steps is not unidirectional. For example, individuals who have entered care and initiated antiretroviral therapy may fail to persist in care and experience treatment lapses that result in HIV disease progression. Consequently, it is useful to envision a continuum of care for HIV-infected individuals, spanning the range from being unaware of one’s HIV status to being fully engaged in HIV medical care(Cheever, 2007). A substantial body of literature shows that substance abuse is a barrier at each step in the treatment engagement process, and facilitates treatment non-persistence.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model showing progression along continuum of engagement in HIV care. ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Step 1: Engagement in HIV care

HIV counseling and testing is the necessary prerequisite for engagement in care. It has been estimated that up to one quarter of HIV-infected individuals in the United States is unaware of their status (Branson et al., 2006). Consequently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have taken up a campaign to promote routine HIV testing in clinical care (Bartlett et al., 2008). Soon after the advent of combination antiretroviral therapy, it was reported that this life-saving treatment was underutilized by HIV-infected drug users compared to other HIV risk groups, and that a major mediator was low levels of engagement in longitudinal treatment (Celentano et al., 1998;Celentano et al., 2001;Strathdee et al., 1998).

Suboptimal engagement in care remains a major issue well into the era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. For example, a recent report examined engagement in care among HIV-infected individuals in South Carolina (Olatosi et al., 2009). Because South Carolina has mandatory name-based reporting of HIV serologic tests, CD4 cell counts and HIV RNA levels, researchers were able to assess patterns of engagement in care among 13,042 individuals who had been diagnosed with HIV and were alive in the 3 year period from 2004 to 2006. Individuals were considered to be in care if they had at least one CD4 cell count or HIV RNA measurement in each of the three years, in transitional care if they had laboratory measurements in at least one but not all three of years, and out-of- care if they had no laboratory measurements in the three-year period. The researchers found that only 35% of individuals were in care, while 25% were in transitional care and 40% were out-of-care. Compared to being in care the odds of being in transitional care and being out-of-care were increased by 29% and 65%, respectively, in injection drug users.

Step 2: Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy

Other studies have suggested that even after substance abusers attend an HIV clinic they have poorer access to antiretroviral therapy compared to other exposure groups. A study conducted at the Johns Hopkins HIV clinic (Lucas et al., 2001), which included 764 patients who participated in confidential interviews, found that the rate of antiretroviral therapy use was similar in individuals with no history of injection drug use and of those with a history of injection drug use who had been abstinent for more than six months. In contrast, the use of antiretroviral therapy was dramatically lower in individuals who reported active injection drug use in the previous month. Similar findings have been reported for alcohol abuse (Chander et al., 2006). It is likely that both patient factors, such as more missed clinic visits and social instability (Lucas et al., 1999), and clinician factors, such as reluctance to prescribe antiretroviral therapy to active drug users, play a role in delayed access to antiretroviral therapy in this group. However, a French study found that active drug users were less likely to be prescribed antiretroviral therapy irrespective of whether or not their medical provider perceived them as actively using drugs (Carrieri et al., 1999).

Step 3: Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy

Once antiretroviral therapy is accepted by patients and prescribed by their clinicians, high levels of medication adherence are required indefinitely to achieve durable suppression of viral load (Paterson et al., 2000). Active drug use has been shown to reduce antiretroviral medication adherence. One group measured antiretroviral adherence with electronic pill-bottle monitors in 77 individuals with a history of drug use (Arnsten et al., 2002). The researchers found that electronically measured adherence was 68% in those who were not using cocaine compared to just 27% among participants who were using cocaine. Corroborating this dramatic difference in measured adherence, was that viral load suppression was achieved by 46% who were not using cocaine compared to just 13% of active users. Another study conducted in British Columbia, assessed differences in viral load suppression in HIV-infected injection drug users compared to other transmission risk groups. The investigators found that HIV-infected injection drug users were less likely to achieve viral suppression than non-drug users, but that this difference appeared to be completely explained by differences in medication refill adherence (Wood et al., 2003).

Step 4: Long-Term Retention to Care

After appropriate treatment is begun, management of HIV infection is a lifelong endeavor, with lapses in follow-up and treatment interruptions being common. In a cohort of HIV-infected injection drug users followed in Baltimore, 78% of participants had at least one non-structured treatment interruptions over a median follow-up of 4.5 years (Kavasery et al., 2009). Giordano and colleagues examined the number of quarters that patients attended the HIV clinic visits following antiretroviral therapy initiation in a sample of 2619 HIV-infected men in the Veterans Administration who survived at least 1 year after starting antiretroviral therapy (Giordano et al., 2007). Compared to attending the clinic in all four quarters, the relative risk of mortality (after the first year) was increased by 42%, 67%, and 95% in those who attended visits in 3, 2, or 1 quarter, respectively. In this study, inconsistent HIV clinic follow-up was strongly associated with injection drug use.

Treatment outcomes in HIV-infected drug users

Most observational studies suggest that clinical outcomes among HIV-infected individuals with a history of injection drug use are poorer than in other transmission risk groups. For example, Johns Hopkins researchers found that the rate of new AIDS defining conditions was similar between drug users and non-drug users in 1996, prior to the availability of combination antiretroviral therapy (Moore et al., 2004). In calendar years following 1996 the rate of AIDS defining conditions declined in both injection drug users and non-drug users. However, the decline was smaller in the former than the latter group. Consequently, by 2002 the relative risk of HIV disease progression was approximately twice as high in HIV-infected drug users as in their non-drug-using counterparts. A longitudinal study in the same cohort found that, compared to non drug users, the risk for new AIDS defining conditions was increased in injection drug users only during semesters when they reported active drug use, not during semesters when they reported abstinence from drug use (Lucas et al., 2006).

Recently studies have highlighted the particularly deleterious effect of crack cocaine use among HIV-infected persons. Studies among HIV-infected women in the US (Cook et al., 2008)and HIV-infected individuals in French Guiana (Nacher et al., 2009) each found that crack cocaine use more than tripled the risk of HIV-disease progression. Another group (Baum et al., 2009) found crack cocaine use to be associated with more rapid CD4 cell decline, including a subset of individuals who were not receiving antiretroviral therapy – suggesting an independent effect of crack cocaine on HIV disease progression. Although injection drug use is generally associated with poorer HIV clinical outcomes compared to other transmission groups (Kitahata et al., 2009;Egger et al., 2002), this is not universally the case. A cohort study in British Columbia recently reported that, after adjustment for adherence, all cause and non-accidental mortality rates were similar among HIV-infected injected drug users and non-users - a finding perhaps attributable to reduced financial barriers to treatment and optimized service delivery for injection drug users in this region (Wood et al., 2008).

Strategies for improving treatment outcomes in HIV-infected patients

Several strategies have shown promise for improving engagement in treatment and treatment outcomes among HIV infected substance abusers.

Substance abuse treatment

The provision of effective treatments for substance abuse appears to facilitate engagement in HIV treatment and improved treatment outcomes in HIV-infected substance abusers. In an observational cohort study, Wood and colleagues found that the time to initiation of antiretroviral therapy was significantly faster among drug users who were receiving methadone maintenance treatment at baseline compared to drug users were not participating in methadone maintenance (Wood et al., 2005). Several other observational studies have linked substance abuse treatment with use of antiretroviral therapy, adherence, viral suppression, and CD4 cell changes (Sambamoorthi et al., 2000;Kapadia et al., 2008;Palepu et al., 2006;Moatti et al., 2000).

The World Health Organization has endorsed the provision of opioid substitution therapy (with either methadone or buprenorphine) as part of a comprehensive package that countries should provide for injection drug users (World Health Organization United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2009). However, the availability of evidence-based treatment for substance abuse is woefully inadequate worldwide. For example, a recent review reported that opioid substitution therapy is unavailable in 66 countries, which are home to an estimated 34% of the global injection drug using population (Mathers et al., 2010). Moreover, even in countries where evidence-based services for injection drug users are available, supply is virtually always short of demand. In the U.S., it is estimated that methadone treatment slots are only available for less than 25% of those who need treatment, a fact that was employed with success to lobby for legislation passed in 2000 that permits physicians to prescribe schedule III medications (buprenorphine and buprenorphine/naloxone) for the purpose of treating opioid-dependent individuals (Fiellin and O'Connor, 2002).

Integrated models of HIV/substance abuse treatment

Integrated care models have resonance in the medical management of HIV because of the high prevalence of substance abuse in this population. Integrated treatment strategies have been proposed as a way to deliver care for comorbid conditions more efficiently and effectively. One randomized trial of 51 methadone maintenance patients who had at least one untreated medical condition, found that 72% of subjects assigned to receive on-site medical care in the methadone clinic attended at least two clinic visits compared to just 6% who were assigned to receive treatment at a nearby medical clinic (Umbricht-Schneiter et al., 1994). Other studies have also found benefits to providing integrated substance abuse and medical treatment in selected populations (Willenbring and Olson, 1999;Weisner et al., 2001). Recently, we reported that on-site treatment of opioid-dependent participants with buprenorphine/naloxone in an HIV clinic led to improved substance abuse treatment outcomes compared to the traditional model of referring subjects to an opioid treatment program (Lucas et al., 2010). Integrated HIV and substance abuse treatment is an idea that makes sense and has long been advocated. However, historical, institutional, and reimbursement frameworks often impede the integration of medical and psychiatric services. Innovation on the policy level is needed to create incentives within the system that foster integrated care.

Directly observed therapy

The success of directly observed therapy in the treatment of tuberculosis (Chaulk and Kazandjian, 1998) sparked interested in applying this strategy to HIV infection (Lucas et al., 2002). To date, several models of directly observed therapy for HIV treatment have been assessed in randomized trials, with mixed results. Two studies recruited largely antiretroviral therapy-naïve individuals with low numbers of injection drug users (Gross et al., 2009;Wohl et al., 2006). Neither of these studies found that directly observed therapy increased rates of viral suppression compared to self-administered therapy. However, two other studies, which targeted predominantly active drug and alcohol abusers with a history of adherence problems, found evidence that directly observed therapy was efficacious compared to self-administered therapy (Altice et al., 2007;Macalino et al., 2007). Recently, a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of directly observed therapy found no evidence overall that directly observed therapy led to improved rates of viral load suppression compared to self-administered therapy (Ford et al., 2009). However, in subset analyses, the authors found that among studies enrolling drug users, homeless individuals, or populations at high risk for non-adherence, directly observed therapy was associated with a 31% increase in the relative rate of viral suppression (95% CI 0% to 71%). It has been proposed that directly observed therapy is likely to be of marginal benefit in unselected patient groups, but may have a role in selected populations of active substance abusers or individuals with insurmountable barriers to medication adherence (Flanigan and Mitty, 2006;Bangsberg et al., 2001). However, to be embraced in clinical care, further research is needed to define the efficacy of directly observed therapy in such high-risk groups, and to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of directly observed therapy relative to other interventions that might be used in these populations.

Incentives

Contingency management is the use of incentives to reinforce desired behaviors. In clinical trials, contingency management has frequently been shown to be effective in reducing or stopping substance abuse, particularly stimulant abuse (Stitzer and Petry, 2006). In recent years, incentive-based strategies have garnered attention for potential use in mainstream medical settings to address behaviorally mediated health problems (Loewenstein et al., 2007) including, weight loss (Volpp et al., 2008), smoking cessation (Volpp et al., 2009b), and adherence with medications. Several small clinical trials have assessed the efficacy of incentive-based interventions for improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy (Sorensen et al., 2007;Javanbakht et al., 2006;Rosen et al., 2007;Rigsby et al., 2000). Three of these studies found that incentives for electronically-measured adherence produced statistically significant improvements in adherence during the intervention period (Sorensen et al., 2007;Rosen et al., 2007;Rigsby et al., 2000), and two studies suggested that incentive-based interventions lead to improved virologic responses (Javanbakht et al., 2006;Rosen et al., 2007). In an African study, small incentives were found to approximately double the rate at which individuals returned to learn the results of their HIV tests (Thornton, 2008).

While the use of incentives to promote engagement in HIV care and adherence with antiretroviral therapy deserves additional study, incentive-based approaches face several challenges (Volpp et al., 2009a;Schmidt et al., 2010;Marteau et al., 2009). First, some incentive-based approaches have involved large financial rewards (e.g., up to $1200 over 12 weeks), and it is not clear if allocation of healthcare resources in this way would be feasible or advisable. Second, it may be unfair to provide rewards for a subset of individuals (e.g., those with poor adherence) while not offering incentives to others (e.g., adherent persons). However, it is costly and inefficient to reward those who would have been adherent without incentives. Finally, existing studies of contingency management approaches for antiretroviral therapy have found that adherence wanes rapidly (to levels in the control groups) when incentives were discontinued (Rigsby et al., 2000;Rosen et al., 2007;Sorensen et al., 2007), raising additional questions about the sustainability of incentive-based approaches.

Conclusions

Substance abuse is a common comorbidity in HIV-infected individuals. Current - but not past - substance abuse adversely affects engagement in care, acceptance of antiretroviral therapy, adherence with therapy, and long-term persistence in care. Substance abuse treatment appears to facilitate engagement in HIV care, and access to evidence-based treatments for substance abuse is central to addressing the HIV epidemic. However, the availability of substance abuse treatment, while variable, is inadequate in almost all settings. Continued efforts to prioritize and fund these services are needed. Integrated care models, in which coordinated substance abuse treatment and HIV care is provided in a single location, hold promise and warrant additional research. Directly observed HIV treatment may have role in selected groups of individuals with advanced HIV disease and major barriers to adherence. Incentive-based approaches have shown promise in some disease models, but face implementation and sustainability challenges.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: Dr. Lucas is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01DA018577, R01DA026770). The views here express the author’s personal views and not those of the National Institutes of Health, the US Department of Health and Human Services, or the US Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Altice FL, Maru DS, Bruce RD, Springer SA, Friedland GH. Superiority of directly administered antiretroviral therapy over self-administered therapy among HIV-infected drug users: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Clin Infect.Dis. 2007;45(6):770–778. doi: 10.1086/521166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altice FL, Mostashari F, Friedland GH. Trust and the acceptance of and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J.Acquir.Immune.Defic.Syndr. 2001;28(1):47–58. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200109010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Grant RW, Gourevitch MN, Farzadegan H, Howard AA, Schoenbaum EE. Impact of active drug use on antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users. J.Gen.Intern.Med. 2002;17(5):377–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangsberg DR, Mundy LM, Tulsky JP. Expanding directly observed therapy: tuberculosis to human immunodeficiency virus. Am.J.Med. 2001;110(8):664–666. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00729-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JG, Branson BM, Fenton K, Hauschild BC, Miller V, Mayer KH. Opt-out testing for human immunodeficiency virus in the United States: progress and challenges. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(8):945–951. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum MK, Rafie C, Lai S, Sales S, Page B, Campa A. Crack-cocaine use accelerates HIV disease progression in a cohort of HIV-positive drug users. J Acquir.Immune.Defic.Syndr. 2009;50(1):93–99. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181900129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, Clark JE. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm.Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrieri MP, Moatti JP, Vlahov D, Obadia Y, Reynaud-Maurupt C, Chesney M. Access to antiretroviral treatment among French HIV infected injection drug users: the influence of continued drug use. MANIF 2000 Study Group. J.Epidemiol.Community Health. 1999;53(1):4–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celentano DD, Galai N, Sethi AK, Shah NG, Strathdee SA, Vlahov D, Gallant JE. Time to initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected injection drug users. AIDS. 2001;15(13):1707–1715. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109070-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celentano DD, Vlahov D, Cohn S, Shadle VM, Obasanjo O, Moore RD. Self-reported antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users [see comments] JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280(6):544–546. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.6.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander G, Lau B, Moore RD. Hazardous alcohol use: a risk factor for non-adherence and lack of suppression in HIV infection. J Acquir.Immune.Defic.Syndr. 2006;43(4):411–417. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243121.44659.a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaulk CP, Kazandjian VA. Directly observed therapy for treatment completion of pulmonary tuberculosis: Consensus Statement of the Public Health Tuberculosis Guidelines Panel [published erratum appears in JAMA 1998 Jul 8;280(2):134] JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(12):943–948. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.12.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheever LW. Engaging HIV-infected patients in care: their lives depend on it. Clin Infect.Dis. 2007;44(11):1500–1502. doi: 10.1086/517534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JA, Burke-Miller JK, Cohen MH, Cook RL, Vlahov D, Wilson TE, Golub ET, Schwartz RM, Howard AA, Ponath C, Plankey MW, Levine AM, Grey DD. Crack cocaine, disease progression, and mortality in a multicenter cohort of HIV-1 positive women. AIDS. 2008;22(11):1355–1363. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830507f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA. A 41-year-old African American man with poorly controlled hypertension: review of patient and physician factors related to hypertension treatment adherence. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(12):1260–1272. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, May M, Chene G, Phillips AN, Ledergerber B, Dabis F, Costagliola D, D'Arminio MA, de Wolf F, Reiss P, Lundgren JD, Justice AC, Staszewski S, Leport C, Hogg RS, Sabin CA, Gill MJ, Salzberger B, Sterne JA. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360(9327):119–129. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin DA, O'Connor PG. Office-based treatment of opioid-dependent patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(11):817–823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp013579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanigan TP, Mitty JA. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Providing Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy When It Is Most Difficult. Clin.Infect.Dis. 2006;42(11):1636–1638. doi: 10.1086/503916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford N, Nachega JB, Engel ME, Mills EJ. Directly observed antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Lancet. 2009;374(9707):2064–2071. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61671-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbert B, Maguire BT, Bleecker T, Coates TJ, McPhee SJ. Primary care physicians and AIDS. Attitudinal and structural barriers to care [see comments] JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;266(20):2837–2842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, Jr, Suarez-Almazor ME, Rabeneck L, Hartman C, Backus LI, Mole LA, Morgan RO. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect.Dis. 2007;44(11):1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub ET, Astemborski JA, Hoover DR, Anthony JC, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA. Psychological distress and progression to AIDS in a cohort of injection drug users. J.Acquir.Immune.Defic.Syndr. 2003;32(4):429–434. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross R, Tierney C, Andrade A, Lalama C, Rosenkranz S, Eshleman SH, Flanigan T, Santana J, Salomon N, Reisler R, Wiggins I, Hogg E, Flexner C, Mildvan D. Modified directly observed antiretroviral therapy compared with self-administered therapy in treatment-naive HIV-1-infected patients: a randomized trial. Arch.Intern.Med. 2009;169(13):1224–1232. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, Schoenbaum EE, Schuman P, Boland RJ, Moore J. Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: longitudinal analysis from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(11):1466–1474. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javanbakht M, Prosser P, Grimes T, Weinstein M, Farthing C. Efficacy of an individualized adherence support program with contingent reinforcement among nonadherent HIV-positive patients: results from a randomized trial. J Int.Assoc.Physicians AIDS Care (Chic.Ill.) 2006;5(4):143–150. doi: 10.1177/1545109706291706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia F, Vlahov D, Wu Y, Cohen MH, Greenblatt RM, Howard AA, Cook JA, Goparaju L, Golub E, Richardson J, Wilson TE. Impact of drug abuse treatment modalities on adherence to ART/HAART among a cohort of HIV seropositive women. Am.J.Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34(2):161–170. doi: 10.1080/00952990701877052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavasery R, Galai N, Astemborski J, Lucas GM, Celentano DD, Kirk GD, Mehta SH. Nonstructured treatment interruptions among injection drug users in Baltimore, MD. J Acquir.Immune.Defic.Syndr. 2009;50(4):360–366. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318198a800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, Merriman B, Saag MS, Justice AC, Hogg RS, Deeks SG, Eron JJ, Brooks JT, Rourke SB, Gill MJ, Bosch RJ, Martin JN, Klein MB, Jacobson LP, Rodriguez B, Sterling TR, Kirk GD, Napravnik S, Rachlis AR, Calzavara LM, Horberg MA, Silverberg MJ, Gebo KA, Goedert JJ, Benson CA, Collier AC, Van Rompaey SE, Crane HM, McKaig RG, Lau B, Freeman AM, Moore RD. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(18):1815–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G, Brennan T, Volpp KG. Asymmetric paternalism to improve health behaviors. JAMA. 2007;298(20):2415–2417. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas GM, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Highly active antiretroviral therapy in a large urban clinic: risk factors for virologic failure and adverse drug reactions. Ann.Intern.Med. 1999;131(2):81–87. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-2-199907200-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas GM, Chaudhry A, Hsu J, Woodson T, Lau B, Olsen Y, Keruly JC, Fiellin DA, Finkelstein R, Barditch-Crovo P, Cook K, Moore RD. Clinic-based treatment of opioid-dependent HIV-infected patients versus referral to an opioid treatment program: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):704–711. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas GM, Cheever LW, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Detrimental effects of continued illicit drug use on the treatment of HIV-1 infection. J.Acquir.Immune.Defic.Syndr. 2001;27(3):251–259. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200107010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas GM, Flexner CW, Moore RD. Directly administered antiretroviral therapy in the treatment of HIV infection: benefit or burden? Aids Patient.Care STDS. 2002;16(11):527–535. doi: 10.1089/108729102761041083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas GM, Griswold M, Gebo KA, Keruly J, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Illicit drug use and HIV-1 disease progression: a longitudinal study in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am.J Epidemiol. 2006;163(5):412–420. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macalino GE, Hogan JW, Mitty JA, Bazerman LB, Delong AK, Loewenthal H, Caliendo AM, Flanigan TP. A randomized clinical trial of community-based directly observed therapy as an adherence intervention for HAART among substance users. AIDS. 2007;21(11):1473–1477. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32811ebf68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteau TM, Ashcroft RE, Oliver A. Using financial incentives to achieve healthy behaviour. BMJ. 2009;338:b1415. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Ali H, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Mattick RP, Myers B, Ambekar A, Strathdee SA. HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. Lancet. 2010;375(9719):1014–1028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA, Wodak A, Panda S, Tyndall M, Toufik A, Mattick RP. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet. 2008;372(9651):1733–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moatti JP, Carrieri MP, Spire B, Gastaut JA, Cassuto JP, Moreau J. Adherence to HAART in French HIV-infected injecting drug users: the contribution of buprenorphine drug maintenance treatment. The Manif 2000 study group. AIDS. 2000;14(2):151–155. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200001280-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RD, Keruly JC, Chaisson RE. Differences in HIV disease progression by injecting drug use in HIV-infected persons in care. J.Acquir.Immune.Defic.Syndr. 2004;35(1):46–51. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200401010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacher M, Adenis A, Hanf M, Adriouch L, Vantilcke V, El GM, Vaz T, Dufour J, Couppie P. Crack cocaine use increases the incidence of AIDS-defining events in French Guiana. AIDS. 2009;23(16):2223–2226. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833147c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatosi BA, Probst JC, Stoskopf CH, Martin AB, Duffus WA. Patterns of engagement in care by HIV-infected adults: South Carolina, 2004–2006. AIDS. 2009;23(6):725–730. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328326f546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Joy R, Kerr T, Wood E, Press N, Hogg RS, Montaner JS. Antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes among HIV/HCV co-infected injection drug users: the role of methadone maintenance therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84(2):188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, Wagener MM, Singh N. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann.Intern.Med. 2000;133(1):21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigsby MO, Rosen MI, Beauvais JE, Cramer JA, Rainey PM, O'Malley SS, Dieckhaus KD, Rounsaville BJ. Cue-dose training with monetary reinforcement: pilot study of an antiretroviral adherence intervention. J.Gen.Intern.Med. 2000;15(12):841–847. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.00127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen MI, Dieckhaus K, McMahon TJ, Valdes B, Petry NM, Cramer J, Rounsaville B. Improved adherence with contingency management. Aids Patient.Care STDS. 2007;21(1):30–40. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambamoorthi U, Warner LA, Crystal S, Walkup J. Drug abuse, methadone treatment, and health services use among injection drug users with AIDS. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;60(1):77–89. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Voigt K, Wikler D. Carrots, sticks, and health care reform--problems with wellness incentives. N.Engl.J.Med. 2010;362(2):e3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JL, Haug NA, Delucchi KL, Gruber V, Kletter E, Batki SL, Tulsky JP, Barnett P, Hall S. Voucher reinforcement improves medication adherence in HIV-positive methadone patients: a randomized trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(1):54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer M, Petry N. Contingency management for treatment of substance abuse. Annu.Rev.Clin Psychol. 2006;2:411–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095219. 411–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Palepu A, Cornelisse PG, Yip B, O'Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JS, Schechter MT, Hogg RS. Barriers to use of free antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users [see comments] JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280(6):547–549. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton RC. The demand for, and impact of, learning HIV status. American Economic Review. 2008;98(5):1829–1863. doi: 10.1257/aer.98.5.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman GJ, Angelino AF, Hutton HE. Psychiatric issues in the management of patients with HIV infection. JAMA. 2001;286(22):2857–2864. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.22.2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbricht-Schneiter A, Ginn DH, Pabst KM, Bigelow GE. Providing medical care to methadone clinic patients: referral vs on-site care [see comments] Am.J.Public Health. 1994;84(2):207–210. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpp KG, John LK, Troxel AB, Norton L, Fassbender J, Loewenstein G. Financial incentive-based approaches for weight loss: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2631–2637. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpp KG, Pauly MV, Loewenstein G, Bangsberg D. P4P4P: an agenda for research on pay-for-performance for patients. Health Aff.(Millwood.) 2009a;28(1):206–214. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Pauly MV, Glick HA, Puig A, Asch DA, Galvin R, Zhu J, Wan F, DeGuzman J, Corbett E, Weiner J, Audrain-McGovern J. A randomized, controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation. N.Engl.J Med. 2009b;360(7):699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0806819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Mertens J, Parthasarathy S, Moore C, Lu Y. Integrating primary medical care with addiction treatment: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286(14):1715–1723. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenbring ML, Olson DH. A randomized trial of integrated outpatient treatment for medically ill alcoholic men. Arch.Intern.Med. 1999;159(16):1946–1952. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.16.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohl AR, Garland WH, Valencia R, Squires K, Witt MD, Kovacs A, Larsen R, Hader S, Anthony MN, Weidle PJ. A Randomized Trial of Directly Administered Antiretroviral Therapy and Adherence Case Management Intervention. Clin.Infect.Dis. 2006;42(11):1619–1627. doi: 10.1086/503906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Hogg RS, Kerr T, Palepu A, Zhang R, Montaner JS. Impact of accessing methadone on the time to initiating HIV treatment among antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected injection drug users. AIDS. 2005;19(8):837–839. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000168982.20456.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Hogg RS, Lima VD, Kerr T, Yip B, Marshall BD, Montaner JS. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and survival in HIV-infected injection drug users. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(5):550–554. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Montaner JS, Yip B, Tyndall MW, Schechter MT, O'Shaughnessy MV, Hogg RS. Adherence and plasma HIV RNA responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-1 infected injection drug users. CMAJ. 2003;169(7):656–661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Technical guide for countries to set targets for universal access to HIV prevention, treatment and care for injecting drug users. 2009 Available at http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/idu/en.