Abstract

The present report concerns a case of pulmonary nocardiosis in an immunocompetent host. This patient was diagnosed as having smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis and received supervised antitubercular treatment for 6 months from a government run tuberculosis centre (Directly Observed Therapy, Short-Course (DOTS) centre). At 3 months after completion of treatment, she presented with fever and cough with posterior–anterior (PA) view chest x ray showing a cavitary lesion on left upper zone. She was subsequently diagnosed as having a case of pulmonary nocardiosis and responded to oral cotrimoxazole.

BACKGROUND

Nocardial infection is not infrequent in immunocompromised hosts, but uncommon in healthy populations. Pulmonary nocardiosis often mimics tuberculosis clinically and radiologically. As a result, the diagnosis of nocardiosis can be missed or delayed especially in a tuberculosis endemic region.

CASE PRESENTATION

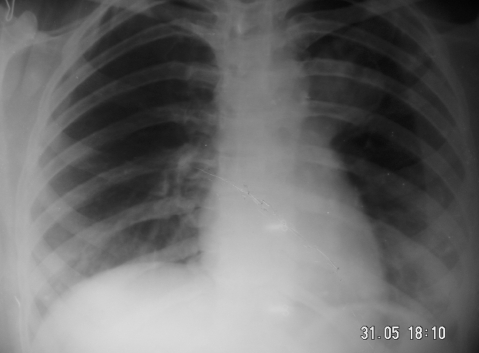

A 27-year-old woman presented with fever and dry cough for 2 weeks, with mild haemoptysis for 3 days. She denied any history of breathlessness, but had similar problems 10 months earlier. At that time, she underwent chest radiography and sputum examination in a government run tuberculosis centre (Directly Observed Therapy, Short-Course (DOTS) centre). On posterior–anterior (PA) view chest x ray, left perihilar opacity was seen (fig 1). Acid-fast bacilli were found in sputum samples. She was diagnosed as having a case of smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis and received isoniazide, rifampicin, pyrizinamide and ethambutol for 2 months, followed by isoniazide and rifampicicn for 4 months under direct supervision. With antitubercular therapy, her symptoms subsided. Repeat sputum samples at the end of 6 months of treatment were negative for acid-fast bacilli and she was declared cured. x Ray of the chest after completion of treatment showed a decrease in the size of the opacity. She remained asymptomatic for the next 3 months.

Figure 1.

Posterior–anterior (PA) view chest x ray showing opacity on left perihilar region.

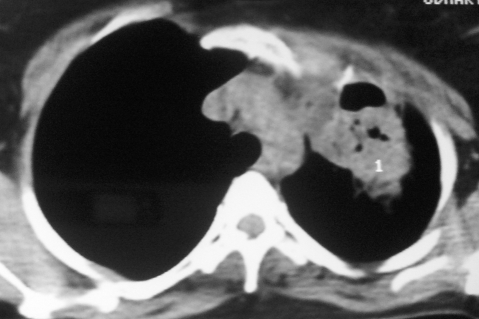

A week prior to presenting to us, she had consulted a doctor for her problems who had advised CT scan of thorax. CT of the thorax (fig 2) showed a large cavitary lesion with necrosis on left upper lobe. On the basis of the CT scan, relapse of pulmonary tuberculosis was suspected and isoniazide, rifampicin, pyrizinamide, ethambutol and streptomycin (injection) were administered.

Figure 2.

CT thorax showing cavitary lesion with necrosis on left upper lobe.

The patient denied any history of diabetes, hypertension and asthma.

On general physical examination, she was conscious, well oriented and well nourished. There was no cervical lymph adenopathy or clubbing. Her respiratory system was within normal limit except for crackles on the left suprascapular region.

INVESTIGATIONS

Haemoglobin: 11.3 gm/dl; white blood cell (WBC) count: 17 700/mm3; neutrophils: 80%; lymphocytes: 15%; monocytes: 1%; eosinophils: 1%; basophil: 4%; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 28 mm in the first hour. A peripheral blood smear for malaria was negative and widal was negative. Liver function, kidney function, blood sugar were normal. The patient’s HIV status was negative.

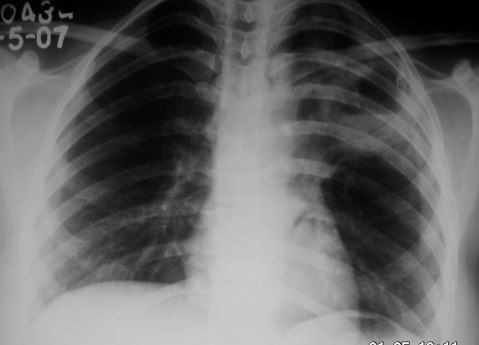

x Ray of the chest showed a cavitary lesion on left upper zone (fig 3). As the patient was unable to expectorate, she underwent bronchoscopy. On bronchoscopy, no endobronchial abnormality was seen. Bronchial brushings and aspirate were taken from all segments of the left upper lobe bronchus and samples were sent for microbiological and cytological examination.

Figure 3.

Posterior–anterior (PA) x ray of the chest showing caviatry lesion on left upper zone.

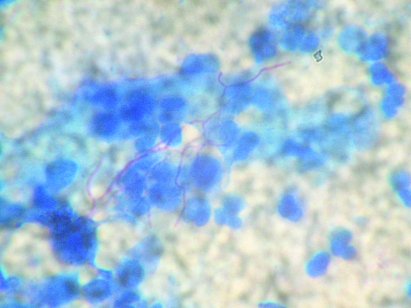

On modified (Kinyoun) Ziehl Neelsen staining of the bronchial aspirate, thin branching filamentous acid-fast organisms suggestive of nocardiosis were seen (fig 4). No mycobacteria, Gram-positive or Gram-negative organisms were isolated. Culture on the MB/BacT system, Lowenstein Jensen medium and Saboraud Dextrose Agar with chloramphenicol failed to grow Nocardia.

Figure 4.

Modified Ziehl Neelsen stain showing thin filamentous acid-fast Nocardia (×100).

TREATMENT

The antitubercular treatment was stopped and cotrimoxazole (sulfamethoxazole 3200 mg + trimethoprim 640 mg/day) in two divided doses was given. Fever subsided within 5 days after the initiation of therapy and WBC count after 7 days of therapy reduced to 8800/mm3 (N75, L21 and M04). She was discharged on oral cotrimoxazole.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Oral cotrimoxazole was continued for 12 months.

Follow-up x ray after 12 months of therapy showed complete resolution of the cavity (fig 5).

Figure 5.

PA view chest x ray at the end of therapy.

DISCUSSION

Nocardia are weakly Gram-positive, filamentous bacteria found in soil. They cause chronic suppurative infection of the skin, lungs and brain. Among the 33 species of Nocardia, Nocardia asteroides are responsible for majority of systemic infection. Pulmonary infections are due to inhalation of the organism.

Nocardial infection can be acute and subacute and have a tendency towards remission and exacerbation. Cell-mediated immunity is necessary to destroy Nocardia; hence nocardial infection is more common in persons with impaired cell-mediated immunity. In a observational study over 13 years involving 31 adult patients with pulmonary nocardiosis, the following predisposing conditions were identified: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (23%), transplantation (29%), HIV infection (19%), alcoholism (6.5%) and treatment with steroids (64.5%).1

Chest radiographic manifestations are pleomorphic and most frequent findings are consolidation, mass lesion with a predilection for upper lobes. The diagnosis of pulmonary nocardiosis should be confirmed by isolation of Nocardia spp. in respiratory secretions. Nocardial infection is infrequent in the normal healthy population. In previously reported series,2,3 patients with pulmonary nocardiosis either had pre-existing COPD or were immunocompromised.

Singh et al4 from India had reported the prevalence of pulmonary nocardiosis was 0.5% in smear positive patients with tuberculosis. In the present case, however, we were not able to rule out the possibility of simultaneous infection with Nocardia and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The patient was diagnosed as having tuberculosis in a DOTS centre and we were not able to review the slide on the basis of which the diagnosis of smear positive tuberculosis was made. It is also possible that broken pieces of nocardial filaments were mistaken for mycobacteria. At the end of 6 months of antitubercular treatment, the DOTS centre had reported that no acid-fast bacilli had been seen in sputum samples and there was a concomitant decrease in the size of the opacity in the lung.Though first line antitubercular drugs are not effective against Nocardia, the patient responded to antitubercular treatment and remained asymptomatic for 3 months. Therefore it remains a matter of conjecture as to whether there was a coinfection with Nocardia, or whether nocardial infection occurred after the tubercular infection.

Sulfonamides are the antimicrobials of choice for nocardial infection. In the case of sulfonamide allergy or a sulfonamide-resistant organism, minocycline, amikacin, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone and imipenem can be used, but the choice should always be guided by the results of in vitro susceptibility testing.

LEARNING POINTS

Early diagnosis of pulmonary nocardiosis requires a high clinical suspicion in a tuberculosis endemic area.

Pulmonary nocardiosis should be considered as a differential diagnosis when tuberculosis fails to respond with standard therapy, or if the patient’s condition worsens despite optimum antitubercular therapy.

In a tuberculosis endemic area, there is the possibility that broken pieces of nocardial filaments could be mistaken for mycobacteria.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCE

- 1.Martínez TR, Menéndez VR, Reyes CS, et al. Pulmonary nocardiosis: risk factors and outcomes. Respirology 2007; 12: 394–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menéndez R, Cordero PJ, Santos M, et al. Pulmonary infection with Nocardia species: a report of 10 cases and review. Eur Respir J 1997; 10: 1542–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curry WA. Human nocardiosis: a clinical review with selected case reports. Arch Intern Med 1980; 140: 818–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh S, Sandhu RS, Randhawa HS, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary nocardiosis in a tuberculosis hospital in Amritsar, Punjab. Indian Chest Dis Allied Sci 2000; 42: 325–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]