Abstract

The present report concerns a patient with a malignant gastrin-producing neuroendocrine tumour (ie, Zollinger–Ellison syndrome) with recurrent hepatic gastrinomas, in whom no gastrinoma in the duodenum, pancreas or other extrahepatic sites could be identified despite the use of multiple, repeatedly performed imaging and exploration techniques over the past 20 years. A short review on primary liver gastrinomas published since 1981 is also given. Interestingly, our patient is the only case with documented recurrent gastrinoma in the liver. None of the cases in the literature had liver gastrinomas as part of the multiple endocrine neoplasia type I syndrome. The interpretation of hepatic gastrinomas as primary lesions is questionable unless comprehensive investigation and well documented long-term follow-up is performed.

BACKGROUND

Zollinger–Ellison Syndrome (ZES) is caused by a malignant gastrin-producing neuroendocrine tumour (ie, a gastrinoma). Symptoms associated with ZES are acid peptic disease, malabsorption and diarrhoea. Most frequently ZES occurs as a sporadic disease, while 20 to 30% of the cases is part of the multiple endocrine neoplasia type I syndrome (MEN-1). This autosomal dominant disorder, caused by mutations of the MEN-1 tumour suppressor gene located on chromosome 11q13, is characterised by multiple tumours in several neuroendocrine organs and tissues. In case of endocrine symptoms in combination with a positive family history for MEN-1 and aberrant levels of calcium, prolactin, parathyroid hormone or pancreas polypeptide, MEN-1 can be suspected and confirmed by genetic analysis.1

Gastrinomas are frequently located in pancreas, duodenum or lymph nodes, in the so-called gastrinoma triangle who’s “points” are formed by the junction of the cystic duct and common bile duct, the junction of the second and third part of the duodenum and the junction between the neck and body of the pancreas. Other gastrinomas (extrapancreatic, extraduodenal and extralymphatic) are called ectopic, and have been reported to occur in the thymus, ovaries, liver, jejunal mesenterium, stomach, heart, parathyroid glands, kidneys and common bile duct. The risk of hepatic metastases of primary gastrinomas is relatively low and primary hepatic gastrinomas are even more rare.2

In this case report, we describe a patient with ZES with recurrent, most likely primary, hepatic gastrinomas and an extended follow-up of almost 20 years after the diagnosis and more than 30 years after the first clinical presentation. Despite extensive monitoring and evaluation, including multiple physical examinations, endoscopies and extensive imaging studies, no primary duodenal or pancreatic gastrinoma could be identified in this patient. Instead, liver tumours suspected of being primary gastrinomas have been resected twice. Furthermore, we discuss the existence of primary liver gastrinomas in general, based on information from 16 case reports from the literature.

CASE PRESENTATION

In 1989, a 39-year-old white man of Hispanic origin was referred to the outpatient clinic of the gastroenterology department of the Leiden University Medical Center, for localisation and treatment of a suspected gastrinoma. At that time symptoms including diarrhoea, gastric complaints, pyrosis, nausea and vomiting had been present for many years. Furthermore, the patient reported a remarkable weight loss of more than 5 kg during a period of approximately 6 months. Fasting serum gastrin (FSG) was elevated and the secretin provocation test was positive, supporting the diagnosis of ZES. The gastric acid-reducing proton pump inhibitor omeprazole 80 mg/day provided relief of his symptoms. The patient was taking no other medication. About 15 years before presentation, the patient had undergone antireflux surgery (Nissen fundoplication). His past medical history was otherwise unremarkable, and his family history was non-contributory. Physical examination revealed no abnormalities, apart from severe scoliosis. Laboratory studies, including serum amylase, electrolytes, liver chemistry, blood cell counts and stool parameters were found normal, except for an increased faecal fat excretion (53 g/day). Gastroduodenoscopy showed Barrett oesophagus, a small duodenal ulcer, and prominent red gastric folds and several erosions in the stomach. Further laboratory analysis revealed an increased FSG of 889 ng/litre, an elevated basal acid output (40 mmol/h; normal <12 mmol/h) with a maximum acid output of 60 mmol/h. Serum levels of calcium (2.36 mmol/litre), parathyroid hormone (2.4 pmol/litre), prolactin (4.9 μg/litre) and pancreas polypeptide (10 pmol/litre) were within normal limits, making a diagnosis of MEN-1 very unlikely.

INVESTIGATIONS

To localise a possible gastrinoma, several imaging studies were performed. However, no tumour was identified at that time by conventional procedures, such as CT, MRI, selective arteriography and selective arterial secretin injection test. Endoscopic ultrasound did not show a tumour in gastroduodenum, pancreas or lymph nodes. Moreover, indium111-somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS), a technique that was at that time still in the experimental phase, was performed (University Hospital, Rotterdam). This scan revealed a possible localisation of the tumour in the left liver lobe or gastric lesser curvature. To exclude a gastric localisation, gastroscopy was repeated. However, no tumour was visualised. Consequently, in 1990, an explorative laparotomy was performed but again no gastrinomas were visible macroscopically. Peroperative ultrasonographic evaluation of the pancreas showed no abnormalities, while peroperative echography of the liver showed a lesion next to the inferior vena cava in the left liver lobe. Biopsies from this lesion were analysed by immunohistochemistry on paraffin-embedded and frozen sections of the tumour, and were found to be positive for keratin, synaptophysin, gastrin and neuron specific enolase but negative for other neuroendocrine markers. Based on these results, a liver localisation of a gastrin-producing neuroendocrine tumour was suggested. In order to localise a primary tumour, peroperative selective venous sampling for gastrin was performed. No evidence of tumour localisation in the duodenopancreatic area was found.

TREATMENT

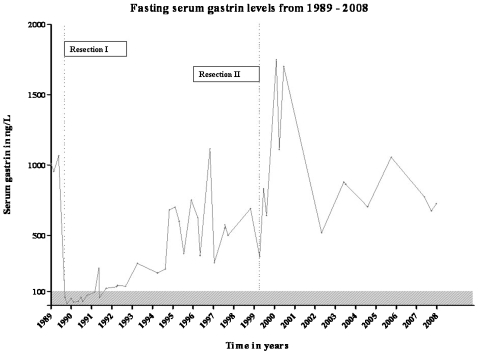

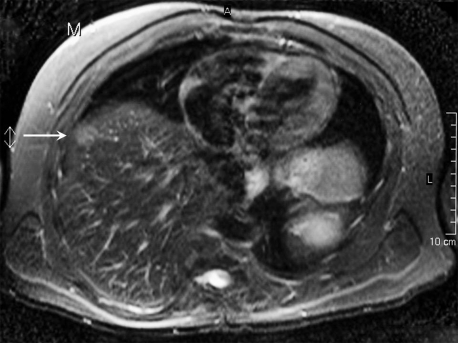

Resection of liver segment II was performed. Histological examination confirmed that the specimen sampled from the liver contained a gastrinoma. Within 5 days after the partial resection, FSG had decreased to normal (60 ng/litre; fig 1). Approximately 1.5 years after surgical excision of the liver gastrinoma, FSG increased to levels above the upper limit of normal (<100 ng/litre). Secretin provocation test was also positive (a gastrin rise of 296 ng/litre after secretin injection). In the period from 1991 until 1999, several imaging techniques were performed without any detection of a pancreatic or duodenal gastrinoma. Multiple gastroscopies repeatedly revealed Barrett oesophagus and oedematous folds in the gastric body. In 1995, a selective arterial secretin injection test was repeated and showed a small increased gradient of serum gastrin over the hepatic vein. In 1998, octreotide scintigraphy (SRS) revealed multiple small liver lesions, which were confirmed on CT and MRI (fig 2). The patient had a partial resection of liver segments IVa and IVb. Postsurgically, FSG initially dropped from 690 to 347 ng/litre but rapidly increased thereafter. A secretin provocation test, performed 3 months postoperatively, resulted in a gastrin increase from 883 to 4675 ng/litre. The patient received gastric acid reducing treatment and remained under follow-up control for the next period.

Figure 1.

Fasting serum gastrin levels (ng/litre), measured on multiple occasions during the evaluation from 1989 until 2008, are presented. The grey region represents the area in which serum gastrin is within normal limits (<100 ng/litre). Dotted lines indicate the first and second partial liver resections in 1990 and 1999, respectively.

Figure 2.

MRI shows a liver lesion ventrolateral in the right liver lobe (Leiden University Medical Center, Department of Radiology).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

No ZES-related complaints were present. In 2003, octreotide scintigraphy (SRS) revealed a dubious accumulation of radioactivity in the ventral right liver lobe, while contrast-enhanced CT and MRI scans of the abdomen were repeatedly normal. In 2006 the liver lesion was confirmed on MRI of the abdomen. To date, no lesion in the pancreas or duodenum has been identified. In 2008, an attempt to treat the hepatic lesion with radiofrequency ablation was performed. However, the procedure was discontinued because of failure of the needle to reach the tumour. To date, serum gastrin levels remain increased although the patient is doing well without symptoms, using 80 mg/day of pantoprazole.

DISCUSSION

This is an exceptional case of a patient with ZES with recurring hepatic gastrinomas in the absence of MEN-1. In the literature, we found 16 cases of “primary” hepatic gastrinomas, reported from 1981 to 2006.3–7 Moruira et al studied the cases of five primary hepatic gastrinomas from the literature and added one case, and concluded that these gastrinomas occurred in slightly younger patients.3 Furthermore, Diaz et al reported that primary hepatic gastrinomas are more common in men, and are not associated with MEN-1.4 Our relatively young male patient has ZES not as part of the MEN-1 syndrome, consistent with the interpretation of the liver lesion as a primary tumour.

In general the majority of sporadic gastrinomas are localised in the gastrinoma triangle;2 thus, accurate evaluations to identify a tumour in this area were initiated, which included preoperative and postoperative CT, MRI, ultrasonography, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy or octreotide scintigraphy, selective angiography, gastroduodenal endoscopic ultrasonography and more specialised tests such as selective arterial secretin injection and selective portal venous sampling8 over the past 20 years, but no evidence for an extrahepatic origin of the gastrinoma was found. Nevertheless, the possibility of a pancreatic, duodenal or other localisation of a primary gastrinoma is difficult to definitely exclude, particularly since the liver is a frequent site for metastatic gastrinomas and these hepatic gastrinomas can be incorrectly interpreted as primary. The probability that liver gastrinomas are by mistake diagnosed as primary is also mentioned by Tiomny et al.5 In most of the cases in the literature, hepatic gastrinomas were defined as primary when no extrahepatic tumour had been found preoperatively, intraoperatively and postoperatively or when postpartial hepatectomy serum gastrin levels declined to the normal range (<100 ng/litre). The tumour is defined as primary preoperatively in only one case report, based on percutanous transhepatic venous sampling.6 In our patient, no lesions outside the liver were found and immunohistochemical analysis of the liver lesions for gastrin confirmed the diagnosis of gastrinoma, fitting the criteria to define the liver gastrinoma as primary. However, serum gastrin levels did normalise after the first partial liver resection, but became abnormal after about 1.5 years and remained increased after the second operation. Therefore, we have to state that the possibility of an extrahepatic gastrinoma being present in these cases cannot be absolutely excluded, although it is very unlikely that any extrahepatic tumour, albeit small in size, is constantly missed even with recent improved MRI and CT techniques that are able to detect gastrinomas of any size at any location. Furthermore, we believe that if any small gastrinoma did exist in the pancreas or duodenum, this tumour would grow and therefore be detectable by now. In addition, in this patient, exclusively liver gastrinomas have been detected, resected and recurred twice. To date, a suspicious liver lesion has been seen with multiple imaging modalities. Although we are not sure if this liver lesion is a new recurrence or growth of a residual tumour after the second partial liver resection, it is clear that the liver tumour(s) has/have a slow growing rate. After the initial resection of the liver gastrinoma in 1990, it took about 9 years before a recurrent tumour became visible on imaging. After the resection in 1999, imaging techniques were initially negative before hepatic lesions could be visualised on MRI in 2006. Thus, to our knowledge this is the first patient with recurrent liver gastrinomas. Except for a single postsurgically detected lymph node metastasis,4 none of the 16 cases from the literature reported recurrence of the liver gastrinoma. However, in most cases the follow-up of the patient after resection of the liver gastrinoma was relatively short (<3 years, range 13–132 months), and had a limited postoperative documentation restricted to FSG measurements and/or one CT scan.5,6 The low risk of metastases from extrapancreatic gastrinoma2 is consistent with the assumption that our patient represents the first reported case of a recurrent primary liver gastrinoma.

In some cases of ZES, patients have undergone a total gastrectomy, preventing the use of acid peptic complaints as marker for recurrence, while in other cases, the follow-up after resection relies only on the analysis of serum gastrin levels. We believe that, even in the absence of ZES-related complaints or in case of normalisation of serum gastrin immediately postoperatively, recurrence may occur, although many years later. Therefore, repeated serum gastrin measurements and investigational imaging, such as octreotide scintigraphy or gastroduodenal endoscopic ultrasound, are required for an adequate follow-up.

In conclusion, we report on an exceptional patient with ZES with recurrent liver gastrinomas, without any other localisation of a primary gastrinoma during evaluation for almost 20 years, and put this observation in the context of the literature on primary liver gastrinomas. The absence of a primary gastrinoma outside the liver during this long follow-up is highly suggestive in defining the gastrinoma in the liver as primary. We propose that frequent measurements of serum gastrin in combination with repeated imaging investigations are indicated after resection of a liver gastrinoma, and that the follow-up period should last for many years, as we show in our patient that a primary hepatic tumour can recur.

LEARNING POINTS

The existence of primary hepatic gastrinomas is rare.

To exclude the existence of extrahepatic gastrinoma, an investigational search including multiple imaging studies is necessary.

A long postoperative follow-up of >3 years including several gastrin measurements and imaging studies is essential to exclude recurrence of hepatic gastrinomas.

Acknowledgments

The help of Lianne Brakenhoff and Gerard-Peter Frank for readability of the manuscript is highly appreciated.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fendrich V, Langer P, Waldmann J, et al. Management of sporadic and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 gastrinomas. Br J Surg 2007; 94: 1331–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu PC, Alexander HR, Bartlett DL, et al. A prospective analysis of the frequency, location, and curability of ectopic (nonpancreaticoduodenal, nonnodal) gastrinoma. Surgery 1997; 122: 1176–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moriura S, Ikeda S, Hirai M, et al. Hepatic gastrinoma. Cancer 1993; 72: 1547–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diaz R, Aparicio J, Pous S, et al. Primary hepatic gastrinoma. Dig Dis Sci 2003; 48: 1665–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiomny E, Brill S, Baratz M, et al. Primary liver gastrinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol 1997; 24: 188–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibata C, Naito H, Funayama Y, et al. Diagnosis and surgical treatment for primary liver gastrinoma: report of a case. Dig Dis Sci 2006; 51: 1122–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delgado J, Delgado B, Sperber AD, et al. Successful surgical treatment of a primary liver gastrinoma during pregnancy: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 191: 1716–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klose KJ, Heverhagen JT. Localisation and staging of gastrin producing tumours using cross-sectional imaging modalities. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2007; 119: 588–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]