Abstract

Seventeen cases of subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE) associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) have been reported. Fifteen such cases have been associated with c-ANCA postivity and two with dual p-ANCA and c-ANCA antibodies. The authors describe a 61-year-old man with sole p-ANCA positive autoantibodies on immunofluorescence presenting with Staphylococcus aureus SBE of the aortic valve. To the best of our knowledge this is the only reported case of sole p-ANCA positive SBE. Full recovery was achieved with antibiotic treatment. ANCAs are known to be associated with infection and their characterisation in acute illness is key in differentiating a true vasculitis from an infection. Unnecessary immunosuppression can be prevented with full investigation of such patients, including both immunofluorescence and ELISA.

Background

Endocarditis can present in many guises and is often overlooked. Diagnosis is hampered by non-specific symptoms and can be made more difficult by association with autoantibodies. It is well-documented that infection can cause temporary rises in autoantibodies and may even precipitate autoimmune disease.1 There have been several case reports of subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE) associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs)—typically c-ANCA proteinase 3 (PR3). We describe a patient with p-ANCA positive endocarditis without development of small vessel vasculitis—the first of its kind to be reported.

This case illustrates how SBE can masquerade as a small vessel vasculitis; thus, hampering diagnosis and treatment. Recognising temporary rises in both c-ANCA and p-ANCA in the setting of infection is crucial to prevent unnecessary and possibly dangerous immunosuppression.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old man presented to his local hospital with diabetic ketoacidosis. He had had diabetes for 10 years and had recently required insulin to help control his blood sugars. He gave a further, somewhat vague, history of general ill health, malaise, anorexia, dry cough, dysuria, falls and urinary incontinence for 2 weeks prior to admission together with new weakness of the left hand. His symptoms were heralded 2 months ago by cessation of his normal drinking habits of 10 pints of lager per day.

On examination the left hand was cool with clawing of the medial three fingers and complete loss of finger abduction, flexion, extension and thumb flexion and abduction. A lesser degree of weakness was present in the left arm with preserved reflexes and sensation. In the lower limbs power was Medical Research Council grade 4–5/5 bilaterally with normal knee jerks, absent ankle reflexes, a positive left Babinski response and a left hemiplegic gait. His cranial nerves were intact and other systems examinations were unremarkable. Two weeks into his admission he developed a diastolic murmur and splinter haemorrhages.

Investigations

He had a raised white cell count of 25×109/l and C reactive protein of 364 mg/l with deranged renal function. A urine sample grew fully sensitive Staphylococcus aureus for which he was treated with antibiotics in his local medical admissions unit. The patient was then transferred to our hospital for further surgical investigation of his hand after a doppler examination of the arm revealed occlusions of both the left radial and ulnar arteries.

CT angiography characterised the ulnar and radial artery occlusions but, as there was reconstitution of the patient's arteries at the wrist, no intervention was required. While a cause for his symptoms was investigated, the patient was placed on therapeutic dose enoxaparin. Further imaging revealed ill-defined areas of opacification on chest x-ray and MRI of the brain showed small areas of brain infarction involving the right centrum semiovale, posterior aspect of the right precentral gyrus and anterior aspect of the postcentral gyrus (figure 1). A cervical spine MRI raised the possibility of bilateral osteophytic impingement of C7 but without any change in spinal cord signal intensity. CT showed multiple cavitating parenchymal lung lesions (figure 2) and small pleural effusions and a right kidney rupture with haemorrhage. The kidney injury was likely due to a fall the previous day while trying to get to the bathroom precipitating a fall in haemoglobin and requiring transfusion. Despite an improvement in his renal function and inflammatory markers, he continued to become more unwell with erratic blood sugars, confusion and continuing falls.

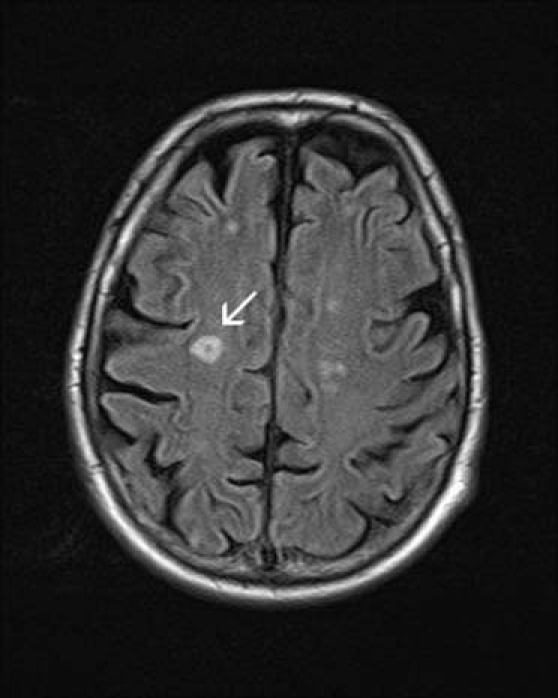

Figure 1.

MRI brain: arrow denotes defined area of hyperintensity.

Figure 2.

CT chest: arrows denote cavitating lesions.

A unifying diagnosis was proving difficult to find until a positive p-ANCA result on immunofluorescence coupled with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 121 mm/h, suggested a vasculitis. Later, myeloperoxidase (MPO) antibodies could not be found on ELISA. Anticardiolipin antibodies were mildly raised at 7.2 GPL U/ml (immunoglobulin G (IgG)) and 9.5 MPL U/ml (IgM). Other autoantibodies, including antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-Ro, anti-La, antiribonucleoprotein, anti-Sm and anti-Jo were negative. A CT-guided lung biopsy of one of the cavities showed normal lung tissue. An infective cause for his symptoms became increasingly more likely with a several S aureus positive blood cultures when the patient's condition worsened and he began to spike occasional temperatures up to 39 °C. Re-examination revealed two splinter haemorrhages in his nails but no heart murmur. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed but failed to identify any vegetative lesions. Subsequently, the patient developed a diastolic heart murmur and a transoesophogeal echocardiagram showed thickening of his aortic valve with a localised area of destruction and severe regurgitation (figure 3).

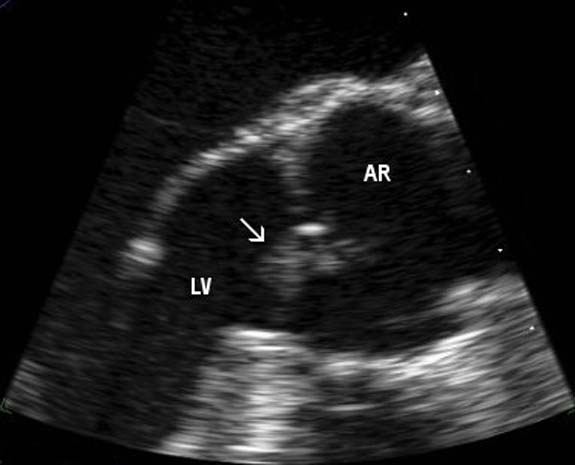

Figure 3.

Transoesophageal echocardiogram showing an aortic valve vegetation (arrow). Aortic root (AR), left ventricle (LV).

Differential diagnosis

The patient presented with several problems: initially a urinary tract infection and diabetic ketoacidosis. A more detailed history revealed that he had been generally unwell for longer; thus, broadening the differential diagnosis. The hand weakness and chest x-ray lesions suggested possible malignancy with direct compression of the brachial plexus by a tumour or indirect paraneoplastic process. The arterial occlusions and the brain MRI findings suggested an embolic problem though no embolic source was found initially. The chest x-ray and CT findings could also have been in keeping with abscesses, tuberculosis or granulomas. The positive p-ANCA seemed to provide the answer with a potential vasculitic cause but looked less likely with positive blood cultures. Once the patient had developed spiking temperatures an infective process, abscess or infective endocarditis became likely and a new heart murmur plus an echocardiogram confirmed the latter to be the true diagnosis.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was treated successfully with a 6-week course of intravenous antibiotics. An echocardiogram at the end of treatment showed that he had residual moderate aortic valve incompetence without evidence of vegetations and preserved good biventricular systolic function. The patient also made excellent progress with the physiotherapists to regain good strength on the left-hand side of his body. A follow-up ANCA was not repeated and he remains well at outpatient follow-up.

Discussion

ANCAs are typically associated with small vessel vasculitides. PR3 and MPOANCA are linked to Wegener's granulomatosis (WG) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), respectively. Various autoantibodies, including anticardiolipin antibodies, cryoglobulins, ANA and ANCA, may also be produced in bacterial and viral infections.1 Unhelpfully, patients with autoimmuine disease, especially systemic lupus erythematosus and the antiphopholipid syndrome, typically present with symptoms similar to those of SBE, sometimes known as Lidman–Sacks endocarditis, and, thus, provide ample opportunity for diagnostic confusion.

To our knowledge, this is the first description of a patient with S aureus SBE as the sole diagnosis in a p-ANCA positive patient presenting with endocarditis (see table 1). It shares some similarities with a case report by Miranda-Filloy et al featuring a S aureus SBE with concomitant MPA (positive p-ANCA).2 This led to the hypothesis that the bacterium may be triggering the vasculitis; however, this is not the case with our patient who remains well after antibiotic treatment. A literature search of the terms ‘endocarditis’, ‘ANCA’, ‘antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody’ in PubMed found a further 17 cases of SBE associated with positive ANCA (see table 2). In two cases there was dual p-ANCA and c-ANCA positivity but c-ANCA alone in the remaining 15.

Table 1.

Cases of p-ANCA positive patients with SBE5

| Paper | Age (y) | Sex | Diagnosis | Organism | p-ANCA/MPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This paper | 61 | Male | SBE | Staphylococcus aureus | Positive (IF) |

| Negative ELISA | |||||

| Tiliakos and Tiliakos5 | 50 | Male | SBE | Streptococcus viridans | Positive (IF) |

| Positive (ELISA) | |||||

| 64 | Male | SBE | S viridans | Positive (IF) | |

| Positive (ELISA) |

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; IF, immunofluorescence; MPO, myeloperoxidase; SBE, subacute bacterial endocarditis.

Table 2.

| Paper | Age | Sex | Organism | c-ANCA/PR3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bauer et al6 | 62 | Male | Streptococcus bovis, Neisseria flava | Positive (IF) |

| Positive (ELISA 512 IU) | ||||

| Sugiyama et al7 | 64 | Male | Bartonella quintata | Positive (ELISA 60 IU) |

| Tiliakos and Tiliakos5 | 50 | Male | S viridans | Positive |

| 64 | Male | S viridans | Positive | |

| Holenarasipur et al8 | 43 | Male | B henselae | Positive PR3-ANCA |

| Zeledon et al9 | 54 | Male | S mutans | Positive (ELISA and IF) |

| Kishimoto et al10 | 50 | Male | S oralis | Positive |

| Fukuda et al11 | 24 | Male | α-Streptococcus | Positive (sandwich ELISA at low titre) |

| Chirinos et al12 | 47 | Male | Enterococcus faecalis | Positive (ELISA 34 U/ml) |

| de Corla-Souza et al13 | 60 | Male | S viridans | Positive (EIA for PR3 2.05 IA units) |

| Positive (IF) | ||||

| 48 | Male | S sanguis | Positive (ELISA 11 IU) | |

| Sandwich ELISA negative | ||||

| Choi et al14 | 72 | Male | S viridans | Positive (IF) |

| Positive (ELISA 199 IU) | ||||

| 73 | Male | S viridans and Staphylococcus lugdunensis | Positive (IF) | |

| Positive (ELISA 44 IU) | ||||

| Subra et al15 | 48 | Male | – | Positive (IF 1:320) |

| Positive (ELISA 12 IU) | ||||

| 46 | Male | – | Positive (IF 1:160) | |

| Positive (ELISA 25 IU) | ||||

| Holmes et al16 | 41 | Male | B henselae | Positive (ELISA 160 IU) |

| Soto et al17 | 79 | Male | S bovis | Positive (200-fold for ANCA-PR3) |

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; IF, immunofluorescence; PR3, proteinase 3; SBE, subacute bacterial endocarditis.

Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) remains the gold standard for ANCA recognition and gives rise to three different patterns of cellular staining. A diffuse, granular cytoplasmic pattern correlates to c-ANCA (usually PR3), while a perinuclear pattern is termed p-ANCA (usually MPO). The third pattern is atypical staining and is a combination of the two. PR3 levels are clinically useful in diagnosis of WG (positive in >90%)3 and levels correlate to disease activity. Anti-MPO is positive in MPA (in about 50% of cases), Churg–Strauss syndrome and WG, but does not correlate with disease activity.4 Using ELISA to quantify the antibody titre has proved extremely useful in monitoring disease progression in WG and formally identifying the precise antibody (MPO or PR3). As a subjective marker of ANCA, IIF results should be followed up with ELISA testing. In our case, the patient was MPO negative despite a positive p-ANCA result and this promoted closer examination and investigation to identify the true cause of his illness.

This case illustrates potential pitfalls in reaching a diagnosis of SBE. Patients with small vessel vasculitis or endocarditis can present in similar ways and with similar laboratory results. When faced with a positive auto-antibody result, the physician should always bear in mind all the causes of raised antibody markers. Making sure that infective causes have been eliminated is crucial before starting patients on immunosuppressive treatments.

Learning points.

-

▶

Infection can be associated with a wide variety of autoantibodies, including ANCA.

-

▶

Positive immunofluoresence should be followed up with ELISA testing.

-

▶

SBE is a great vasculitis mimic and should always be part of the broader differential diagnosis.

-

▶

Immunosuppressive regimes should only be started when infection (SBE) has been excluded.

Acknowledgments

Anna Griffiths (echocardiographer, Guys and St Thomas Hospital NHS Trust) for the help with obtaining the echocardiography image.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Bonaci-Nikolic B, Andrejevic S, Pavlovic M, et al. Prolonged infections associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies specific to proteinase 3 and myeloperoxidase: diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Clin Rheumatol 2010;29:893–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miranda-Filloy JA, Veiga JA, Juarez Y, et al. Microscopic polyangiitis following recurrent Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and infectious endocarditis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2006;24:705–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozaki S. ANCA-associated vasculitis: diagnostic and therapeutic strategy. Allergol Int 2007;56:87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beauvillain C, Delneste Y, Renier G, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies: how should the biologist manage them? Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2008;35:47–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiliakos AM, Tiliakos NA. Dual ANCA positivity in subacute bacterial endocarditis. J Clin Rheumatol 2008;14:38–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer A, Jabs WJ, Süfke S, et al. Vasculitic purpura with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive acute renal failure in a patient with Streptococcus bovis case and Neisseria subflava bacteremia and subacute endocarditis. Clin Nephrol 2004;62:144–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugiyama H, Sahara M, Imai Y, et al. Infective endocarditis by Bartonella quintana masquerading as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated small vessel vasculitis. Cardiology 2009;114:208–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holenarasipur RV, Kirstin Bacani A, DeValeria PA, et al. Bivalvular Bartonella henselae prosthetic valve endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:4081–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeledon JI, McKelvey RL, Servilla KS, et al. Glomerulonephritis causing acute renal failure during the course of bacterial infections. Histological varieties, potential pathogenetic pathways and treatment. Int Urol Nephrol 2008;40:461–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kishimoto N, Mori Y, Yamahara H, et al. Cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positive pauci-immune glomerulonephritis associated with infectious endocarditis. Clin Nephrol 2006;66:447–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuda M, Motokawa M, Usami T, et al. PR3-ANCA-positive crescentic necrotizing glomerulonephritis accompanied by isolated pulmonic valve infective endocarditis, with reference to previous reports of renal pathology. Clin Nephrol 2006;66:202–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chirinos JA, Corrales-Medina VF, Garcia S, et al. Endocarditis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol 2007;26:590–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Corla-Souza A, Cunha BA. Streptococcal viridans subacute bacterial endocarditis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA). Heart Lung 2003;32:140–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi HK, Lamprecht P, Niles JL, et al. Subacute bacterial endocarditis with positive cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and anti-proteinase 3 antibodies. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:226–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Subra JF, Michelet C, Laporte J, et al. The presence of cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (C-ANCA) in the course of subacute bacterial endocarditis with glomerular involvement, coincidence or association? Clin Nephrol 1998;49:15–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes AH, Greenough TC, Balady GJ, et al. Bartonella henselae endocarditis in an immunocompetent adult. Clin Infect Dis 1995;21:1004–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soto A, Jorgensen C, Oksman F, et al. Endocarditis associated with ANCA. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1994;12:203–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haseyama T, Imai H, Komatsuda A, et al. Proteinase-3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA) positive crescentic glomerulonephritis in a patient with Down's syndrome and infectious endocarditis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998;13:2142–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]