Abstract

Pyloric gland-type adenoma of the duodenum with documented malignant progression is rare. A case is presented of an 87-year-old man with bloating and nausea, who on investigation was found to have a polyp on the anteroinferior wall of the duodenal cap. Histologic examination of the polyp showed features of a pyloric gland adenoma (PGA) demonstrating the full spectrum of progression from low- to high-grade dysplasia and finally invasive adenocarcinoma. The carcinoma showed gastric-type differentiation highlighted by its mucin immunohistochemistry profile and was of advanced stage with lymph node metastasis. The literature on PGAs and the little documentations on progression to carcinoma in duodenal PGAs are reviewed.

Background

Pyloric gland adenoma (PGA) is a rare neoplastic polyp with pyloric gland differentiation arising most commonly in the gastric corpus, but also described in extragastric locations including the duodenum.1 Documented cases of duodenal PGA (dPGA) with neoplastic progression are uncommon, with four cases reported in the English literature to the best of our knowledge.1–3 Most of these cases have been associated with superficial or small foci of adenocarcinoma with the associated adenocarcinoma typically showing gastric-type differentiation. PGAs are typically bland in appearance and may represent a potential diagnostic pitfall mimicking benign or reactive entities. They are, however, fully neoplastic with the potential for malignant progression. We hereby report an additional case of PGA of the duodenal bulb demonstrating the full spectrum of progression from dysplasia to invasive adenocarcinoma of advanced stage with lymph node metastasis, together with a discussion of the differential diagnosis and brief review of the literature.

Case presentation

An 87-year-old male presented with bloating and nausea for investigation and on endoscopy had a broad-based 12-mm polyp on the anteroinferior wall of the duodenal cap. Initial biopsies showed intramucosal adenocarcinoma with polypoid dysplastic fragments suggestive of a gastric-type adenoma with pyloric gland-type differentiation. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) of the polyp was attempted, during which a 6-mm flat-based ulcer with mildly elevated edges was discovered in continuity with and distal to the polyp. The resected polyp harboured invasive adenocarcinoma, which was also present in biopsies from the ulcer edge. A subsequent partial gastroduodenectomy was performed.

Investigations (pathological results)

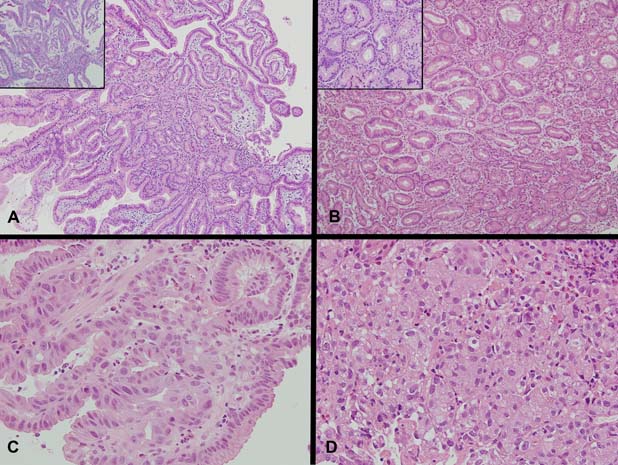

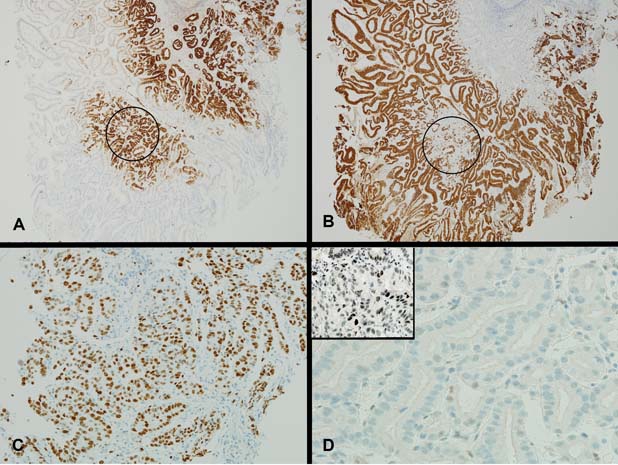

Macroscopically, multiple pieces of tan tissue 1.5–2 mm were received from the initial biopsies and two pieces of mucosal tissue 4 and 10 mm in diameter were received from the EMR. Histologically, both showed a polyp composed of closely packed tubules lined by cuboidal to columnar epithelium with pale to oeosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm and round basal nuclei (figure 1A). Periodic acid-Schiff staining following diastase digestion showed the absence of an apical mucin cap (figure 1A, inset). There was transition to areas with low-grade dysplasia (figure 1B), high-grade dysplasia (figure 1C) and finally intramucosal adenocarcinoma (figure 1D). Mucin immunohistochemistry showed strong expression of MUC6 in the glands of the polyp with MUC5AC expression either of surface epithelium or intermingled co-expression with MUC6 in glands (figure 2A,B). MUC2 and CDX-2 were negative. A high proliferation index was demonstrated within areas of high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal adenocarcinoma (figure 2C). There was no significant nuclear staining for p53 within typical glands of the PGA (figure 2D), however, moderate to strong nuclear staining for p53 was observed within areas of high-grade dysplasia/intramucosal adenocarcinoma (figure 2D, inset). In addition, foci of invasive adenocarcinoma were seen in the EMR and biopsies from the ulcer edge, similar to that found in the subsequent partial gastroduodenectomy.

Figure 1.

(A) Sections demonstrating a polypoid lesion arising among distorted duodenal villi composed of tubular glands lined by columnar epithelium with basal nuclei and pale to oeosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm (H&E ×100, inset PAS with Diastase, ×200). No apical mucin cap is demonstrated within the epithelium of the glands (inset). (B) Sections demonstrating abrupt transition of typical pyloric type glands to glands with low-grade dysplasia showing irregularity of gland outline with elongated, pseudostratified and mildly hyperchromatic nuclei (H&E ×100, inset H&E ×400). Higher magnification showing two glands in the centre with abrupt transition within the same gland from typical bland cytology of pyloric type epithelium to low-grade dysplasia with mildly hyperchromatic and pseudostratified nuclei (inset). (C) High-grade dysplasia with irregular papillary structures and fused irregular glands lined by epithelium showing enlarged nuclei with loss of polarity, nuclear pleomorphism and enlarged nucleoli (H&E ×400). Increasing numbers of mitotic figures are seen. (D) Intramucosal carcinoma with syncytial growth of back-to-back and fused poorly formed microglands and solid clusters of malignant cells with increasing nuclear pleomorphism, loss of polarity and nucleolar prominence (H&E ×400).

Figure 2.

(A) There is strong expression of MUC6 in the glands of the pyloric gland adenoma (MUC6 ×40). In some areas of the polyp, the glands positive for MUC6 also show patchy co-expression of MUC5AC (circled area, compare with circled area in figure 2B). (B) There is expression of MUC5AC either restricted to surface epithelium with lack of staining within the glands of the pyloric gland adenoma or with patchy co-expression within the glands of the pyloric gland adenoma (circled area) (MUC5AC ×40). (C) A high proliferation index is shown within areas of high-grade dysplasia (MIB-1 ×200). (D) Typical glands of pyloric gland adenoma negative for p53 (p53 pyloric gland adenoma ×400, inset p53 pyloric gland adenoma high-grade dysplasia/intramucosal adenocarcinoma ×400). Area of high-grade dysplasia/intramucosal adenocarcinoma with moderate to strong nuclear staining for p53 (inset).

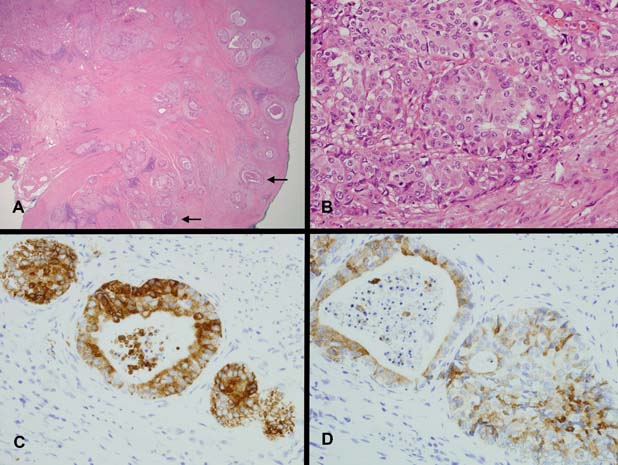

The partial gastroduodenectomy consisted of distal stomach with adjacent duodenal cap harbouring a 10 mm ulcer. Although deceptively small in macroscopic extent, histologically there was extensive adenocarcinoma permeating transmurally with serosal involvement, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion and lymph node metastasis. The adenocarcinoma was variably gland forming, with solid nests and glands, some with comedo-like necrosis (figure 3A). The cells of the adenocarcinoma showed vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli and cytoplasmic characteristics reminiscent of the overlying PGA (figure 3B). Immunohistochemical stains showed MUC6 and MUC5AC co-expression with negative staining for MUC2, similar to parts of the overlying PGA (figure 3C,D). No gastric heterotopia was found despite extensive sampling.

Figure 3.

(A) Invasive adenocarcinoma (H&E ×20). Infiltrating adenocarcinoma with cribriform or cystically dilated glands, cords and solid nests. Some glands show central comedo-like necrosis (arrows). (B) The cells show vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (H&E ×400). The cytoplasm is pale to oeosinophilic with a ground glass quality similar to the cells of the pyloric gland adenoma. (C) There is strong cytoplasmic staining for MUC6 in the cells of the adenocarcinoma (MUC6 ×400). (D) Patchy co-expression of MUC5AC is seen within cells of the adenocarcinoma (MUC5AC ×400).

Differential diagnosis

An unusual hyperplastic or reactive polyp had been entertained on the initial biopsies due to the bland appearance of the polyp. However, dysplastic foci where noted on deeper sectioning of the biopsy material prompting further investigation including mucin-core protein immunohistochemistry allowing the correct diagnosis to be made.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient made a good recovery and remains free of disease 8 months following his surgery.

Discussion

PGAs are neoplastic epithelial polyps most commonly recognised in the gastric corpus and often associated with atrophic gastritis. They have been described in extragastric sites, including duodenum, biliary tree and pancreas with rare cases described in the oesophagus and rectum arising in gastric heterotopia.1–5 In the stomach, they account for 2.7% of all polyps but among neoplastic polyps are surpassed in frequency only by tubular adenomas and polypoid adenocarcinomas.2 They occur mostly in older age groups (mean age 73).1 2 A female predominance is observed in gastric sites but not in the duodenum.1 2 Documented malignant progression in dPGAs is rare. The first case report of a dPGA arising in gastric heterotopia with dysplastic progression of gastric-type was reported by Kushima et al in 1999.3 In the two largest series of PGAs to date, there were a total of three cases of adenocarcinomas arising in dPGAs.1 2 Most cases with malignant progression were associated with superficial or small foci of adenocarcinoma, with one T4N0 adenocarcinoma arising from a dPGA.1 2 The present case is the fifth and showed advanced stage with lymph node metastasis. These are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Cases of duodenal pyloric gland adenoma in the English literature with documented malignant progression

| Author(s) | Year | Type of study | Type of adenocarcinoma arising from dPGA | Extent of adenocarcinoma arising in dPGA | MUC profile of adenocarcinoma arising in dPGA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kushima et al3 | 1999 | Single case reported of dPGA, with malignant progression | Gastric-type | Intramucosal | MUC5AC and MUC6 described as random and deranged, with co-expression of both | |

| Vieth et al2 | 2003 | Case series with a total of 90 PGAs with 30% showing malignant progression | Included in this case series was a single case of dPGA, which showed malignant progression | Gastric-type | The depth of invasive adenocarcinoma in the dPGA was not specified, however, cases with malignant progression mostly showed superficial (limited to mucosa) or small foci of adenocarcinoma with one T2 adenocarcinoma | MUC profile of adenocarcinomas not described |

| Chen et al1 | 2009 | Case series with 41 PGAs with 12.2% showing malignant progression | Included in this case series were a total of 19 cases of dPGA, of which two showed malignant progression | Gastric-type | Of the two dPGAs with malignant progression, one had intramucosal adenocarcinoma, the other showed pancreatic invasion (T4, N0) | MUC5AC and MUC6 co-expression |

| This study | 2010 | Single case report of dPGA, with malignant progression | Gastric-type | Extensive permeation of duodenal wall with serosal involvement, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion and lymph node metastasis (T4, N1) | MUC5AC and MUC6 co-expression |

dPGA, duodenal pyloric gland adenoma; PGA, pyloric gland adenoma.

The pathological features of a high-stage gastric-type adenocarcinoma originating in a dPGA are well illustrated by the present case. PGAs do not have specific gross features, presenting as nodular/dome-shaped lesions with a mean diameter at diagnosis of 16.1 ± 9 mm.2 6 The polypoid component of the tumour in the present case measured 12 mm in diameter. Histologically, the typical lesion is composed of closely packed pyloric gland-type tubules that may be narrow or cystically dilated but not fused or irregularly branching. Dysplasia can be detected, which can be divided into low-grade and high-grade by similar criteria as in the remainder of the gastrointestinal tract.1 PGAs lack an apical neutral mucin cap by mucin histochemistry and express MUC6 (pyloric gland mucin marker) and MUC5AC (a foveolar mucin marker), with the pattern of MUC5AC/MUC6 being either superficial surface/deep glands or intermixed co-expression. They are negative for MUC2, CD10 and CDX-2.1 2 These features were characteristically noted in this case.

The principal differential diagnosis in gastric mucosa is from gastric foveolar adenoma (GFA). Unlike PGAs, GFAs are lined by gastric foveolar epithelium with an apical mucin cap and are positive for MUC5AC but negative for MUC6.1 PGAs are unique in that while fully neoplastic with malignant potential, the typical case is cytologically bland and may mimic unusual reactive or non-neoplastic polyps, which had at one stage been considered as a possibility on the initial biopsies of the present case. In the stomach, they need to be distinguished from unusual hyperplastic polyps. Like hyperplastic polyps, PGAs are associated with autoimmune gastritis but differ by displaying ground glass cytoplasm without apical mucin vacuoles unlike the mucin-rich gastric foveolar epithelium of hyperplastic polyps.1 In the duodenum, PGAs may mimic Brunner's gland adenoma/hamartoma. Morphologically, the distinction may be extremely difficult if not impossible in certain cases. Mucin immunohistochemistry is useful as Brunner's gland adenomas/hamartomas are positive for MUC6 but lack MUC5AC.1 However, as the staining of MUC5AC in PGAs may be variable/patchy in appearance, there may be potential for misdiagnosis on a small biopsy. As such, other markers that may aid in this differential diagnosis would be most useful. One such potential candidate is MUC5b, which is positive in Brunner's glands but negative in the normal adult stomach.7 However, MUC5b expression has been described in the neoplastic stomach, for example, gastric adenocarcinoma.8 To our knowledge, MUC5b expression has not been studied in PGAs and as PGAs are fully neoplastic lesions with the potential for malignant progression, further study of the staining with MUC5b would provide further insight into its potential utility. Our laboratory did not have access to MUC5b and hence this was not available to be performed in this case. It is also important that PGAs are not mistaken for gastric heterotopias. No features of Brunner's gland adenoma/hamartoma or gastric heterotopias were noted in this case.

Adenocarcinomas arising from PGAs have been described as being of gastric-type with MUC6 and MUC5AC co-expression.1 2 This was confirmed in the present case with the adenocarcinoma showing cytomorphologic characteristics reminiscent of pyloric gland-type epithelium together with MUC6 and MUC5AC co-expression and lack of intestinal-type mucin (MUC2).

The origin of PGAs of the duodenum is presently unknown. Some, but not all, cases have been described associated with gastric heterotopia.1–3 Whether gastric heterotopia is a prerequisite or whether they may arise from metaplastic epithelium is unknown. Several studies have described dysplasia and gastric-type adenocarcinoma arising in the duodenum, similar to that seen in the present case, in association with so-called Brunner's gland adenoma/hamartoma/hyperplasia.9 10 It has been suggested that Brunner's glands may participate in the reparative response to mucosal injury by the formation of a new generative zone (‘neo-G zone’) with proliferation of pluripotent stem cells within Brunner's glands and ducts.11 These cells may differentiate towards the surface forming areas of foveolar metaplasia, which is thought to be more resistant to acid pepsin attack; or downwards as Brunner's-type epithelium giving rise to Brunner's gland adenoma/hamartoma/hyperplasia. It is thought that the ‘neo-G zone’ is prone to mutational errors due to the higher proliferation leading to the generation of dysplasia and subsequently carcinoma.9 10 It is interesting to note that the area of the neo-G zone bears some superficial resemblance to PGAs both morphologically and by mucin immunohistochemistry including MUC5AC and MUC6 expression. Although speculative, perhaps these repairative and metaplastic phenomena may give origin to some PGAs as a result of genetic mutations and aberrant proliferation of the ‘neo-G zone’ in the progression towards the development of gastric-type adenocarcinomas. Furthermore, it would be interesting to note what proportion of adenocarcinomas of the duodenum show gastric-type differentiation and whether an alternate pathway of carcinogenesis of adenocarcinomas exists within the small bowel as distinct from intestinal-type adenocarcinomas, perhaps involving PGAs as precursor lesions. These areas require further study.

Data on the molecular pathogenesis of PGAs are sparse. Molecular and genetic studies of PGAs have identified multiple chromosomal losses and gains, some of these shared with gastric-type adenocarcinoma.4 6 12 In their study of gastric type adenomas, including PGAs, Kushima et al found less alterations of p53 in gastric-type adenomas as a whole when compared with intestinal-type adenomas but suggest that p53 may have a role in late progression to gastric-type adenocarcinoma.13 This could perhaps explain the p53 staining pattern observed in the present case with the lack of p53 staining in the typical glands of the PGA and the presence of p53 staining within areas of high-grade dysplasia/intramucosal adenocarcinoma.

Finally, although cytologically bland it should be reiterated that PGAs are neoplastic and precancerous with their unstable and neoplastic nature evidenced by the molecular/genetic findings and documented cases of neoplastic progression. In the two largest series of PGAs to date, the risk of malignant progression ranges from 12% to 30%. In view of this, it is recommended that PGAs are completely removed by polypectomy if found.

Learning points.

-

▶

PGAs are neoplastic polyps despite their bland cytologic appearances and carry a significant potential for neoplastic transformation (up to 30%).

-

▶

PGAs may mimic benign entities which may represent potential pitfalls in diagnosis.

-

▶

Adenocarcinomas arising within PGAs typically show gastric-type differentiation with MUC6 and MUC5AC co-expression.

-

▶

The origin of PGAs of the duodenum and their role in the pathogenesis of adenocarcinomas of the duodenum require further study.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Chen ZM, Scudiere JR, Abraham SC, et al. Pyloric gland adenoma: an entity distinct from gastric foveolar type adenoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:186–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vieth M, Kushima R, Borchard F, et al. Pyloric gland adenoma: a clinico-pathological analysis of 90 cases. Virchows Arch 2003;442:317–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kushima R, Rüthlein HJ, Stolte M, et al. ‘Pyloric gland-type adenoma’ arising in heterotopic gastric mucosa of the duodenum, with dysplastic progression of the gastric type. Virchows Arch 1999;435:452–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kushima R, Vieth M, Mukaisho K, et al. Pyloric gland adenoma arising in Barrett's esophagus with mucin immunohistochemical and molecular cytogenetic evaluation. Virchows Arch 2005;446:537–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vieth M, Kushima R, de Jonge JP, et al. Adenoma with gastric differentiation (so-called pyloric gland adenoma) in a heterotopic gastric corpus mucosa in the rectum. Virchows Arch 2005;446:542–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kushima R, Vieth M, Borchard F, et al. Gastric-type well-differentiated adenocarcinoma and pyloric gland adenoma of the stomach. Gastric Cancer 2006;9:177–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van De Bovenkamp JH, Korteland-Van Male AM, Buller HA, et al. Metaplasia of the duodenum shows a Helicobacter pylori-correlated differentiation into gastric-type protein expression. Hum Pathol 2003;34:156–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinto-de-Sousa J, Reis CA, David L, et al. MUC5B expression in gastric carcinoma: relationship with clinico-pathological parameters and with expression of mucins MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC6. Virchows Arch 2004;444:224–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kushima R, Stolte M, Dirks K, et al. Gastric-type adenocarcinoma of the duodenal second portion histogenetically associated with hyperplasia and gastric-foveolar metaplasia of Brunner's glands. Virchows Arch 2002;440:655–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakurai T, Sakashita H, Honjo G, et al. Gastric foveolar metaplasia with dysplastic changes in Brunner gland hyperplasia: possible precursor lesions for Brunner gland adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:1442–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kushima R, Manabe R, Hattori T, et al. Histogenesis of gastric foveolar metaplasia following duodenal ulcer: a definite reparative lineage of Brunner's gland. Histopathology 1999;35:38–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buffart TE, Carvalho B, Mons T, et al. DNA copy number profiles of gastric cancer precursor lesions. BMC Genomics 2007;8:345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kushima R, Müller W, Stolte M, et al. Differential p53 protein expression in stomach adenomas of gastric and intestinal phenotypes: possible sequences of p53 alteration in stomach carcinogenesis. Virchows Arch 1996;428:223–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]