Abstract

We report on a case of isolated tear of the medial head of gastrocnemius tendon. The patient presented with a painless lump in the right calf and denied any prior history of trauma or strain to the leg. A longitudinal split of the tendon was demonstrated at ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). There were no other abnormalities and the gastrocnemius muscle was normal. There are no reports in the literature of isolated gastrocnemius tendon tear. To date the calf muscle complex injury described in this area is tearing of the medial head of gastrocnemius muscle, sometimes referred to as “tennis leg”. We conclude that an isolated tear of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a lump or swelling in the upper medial area of the calf and we recommend ultrasound or MRI as the investigations of choice.

BACKGROUND

Abnormalities of the calf musculature are extensively reported. The medial head of gastrocnemius muscle accounts for a high proportion of strains to the calf muscle complex. The differential diagnoses listed in the literature include deep vein thrombosis, haematoma, superficial thrombophlebitis, Baker’s cyst, acute compartment syndrome and cellulitis.1 There is no mention of isolated tear to the medial head of gastrocnemius tendon and no such lesion has been described before. For that reason we decided to publish the case. It is important clinically that the possibility of an isolated split or tear of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius is considered in the differential diagnosis of a lump presenting in the medial upper aspect of the calf even in the absence of pain or a history of trauma to the affected area. The isolated tear of the medial head of gastrocnemius tendon may be postulated to be part of the spectrum of injuries in the calf, but the absence of any clear history of trauma to the area in our patient also raises the possibility of chronic tendon tear, tear with minimal trauma or silent and painless tear of the tendon in isolation without injury to the gastrocnemius muscle itself. Muscle rather than tendon injury has up to now been the underlying abnormality described in calf muscle complex injuries, most notably “tennis leg”.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 38-year-old district nurse presented to the accident and emergency department in May 2007 having twisted her left ankle after landing awkwardly whilst playing in a netball tournament. The left ankle was immediately painful, swollen and bruised. She had no other injuries. The attending doctors carried out an examination of the ankle and requested plain radiographs of the foot and ankle. The radiographs were reported as showing “no bony injury”. A diagnosis of ankle sprain and soft tissue injury was made. The patient was advised to rest completely for 24 h, then gradually mobilise, take non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs if necessary after 48 h and apply ice to reduce swelling. In the subsequent weeks the left foot swelling did not completely subside and pain persisted, and the patient remained relatively inactive with limited mobility. Because of the lack of improvement, in July 2007 she again attended the emergency department. Further radiographs were taken. Again no bone injury was seen. She was referred for review by an orthopaedic foot specialist and attended the orthopaedic outpatients department in September 2007. A further plain radiograph was taken. A LisFranc fracture was suspected and CT scan requested. The CT scan demonstrated a LisFranc injury of the left foot. A detached LisFranc fragment as well as a fracture of the base of the second metatarsal was shown. The injury was surgically repaired with plate and screws on 10 January 2008. The patient spent 18 weeks with the left foot and ankle in a plaster cast and using crutches. On 18 February 2008, whilst walking in the kitchen on crutches she “felt a pop” in the right leg. There was no pain and she took no action. Weeks later she felt a painless “lump” in the right calf and consulted her GP at the end of May 2008. He suspected a muscle hernia and advised that she mention it at the next orthopaedic outpatient appointment to review her LisFranc injury. In July 2008 she attended the orthopaedic clinic and enquired about the painless lump in the right calf. She informed the surgeons that the lump must have occurred in recent months as she skin moisturised daily and would have noticed had it occurred earlier. There had been no change in size or other functional problem. At the time she first noticed the lump her mobility was in any case limited to walking on crutches due to the LisFranc fracture of the left foot. The patient denied any history of trauma to the right calf or leg. She was otherwise fit and well with no general medical problems. There was no past history of illness. On clinical examination, a large, smooth longitudinal lump was felt under the skin. The mass had limited sideways mobility. The overlying skin was normal with no discolouration. Due to the history and clinical findings, the main concern of the clinician was a soft tissue sarcoma. Magnetic resonance imaging was requested followed by ultrasound.

INVESTIGATIONS

Ultrasound scan was carried out using a high frequency (5–12 MHz broad band linear array) probe on an Advanced Technology Laboratories (ATL) HDI 5000 machine. This included colour flow Doppler scanning.

The ultrasound was reported showing a mid-substance longitudinal partial tear/split of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius in the distal 6 cm but with entirely normal muscle and no other abnormality. There was organising haematoma centrally within the torn tendon (figs 1–6). A thin outer rim of tendon encircled the haematoma. There was no other abnormality. All surrounding structures including the medial head of gastrocnemius muscle were entirely normal. The myotendinous junction was also normal.

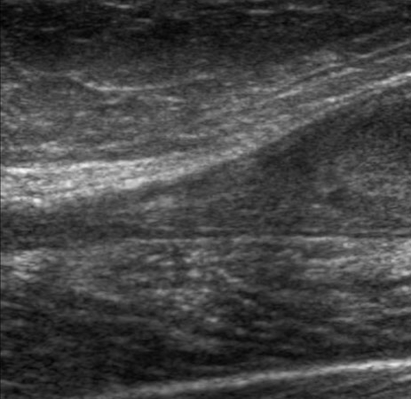

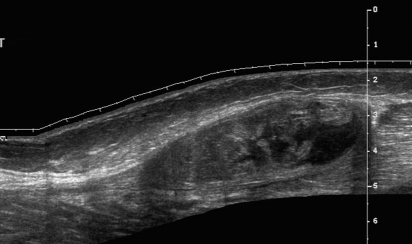

Figure 1.

Ultrasound scan in the sagittal plane showing a widening of the distal half of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius due a longitudinal mid-substance split and tear of the tendon widening distally to the musculo-tendinous junction. The surrounding muscle and soft tissues are normal.

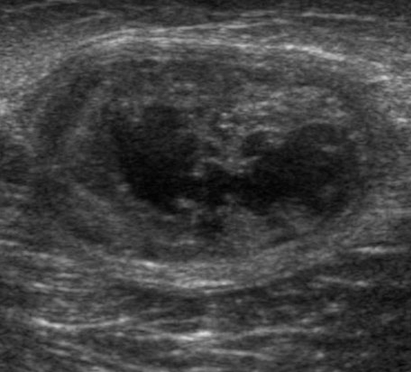

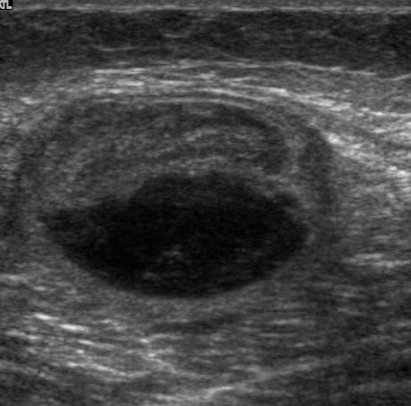

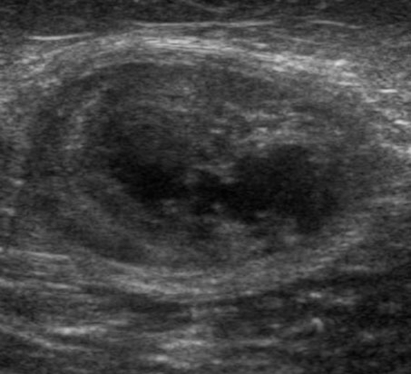

Figure 6.

Ultrasound scan in the axial plane demonstrating organising haematoma within the centre of a widened and torn distal portion of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius.

Figure 2.

Ultrasound scan in the sagittal plane showing a widening of the distal half of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius due a longitudinal mid-substance split and tear of the tendon widening distally to the musculo-tendinous junction. The surrounding muscle and soft tissues are normal.

Figure 3.

Ultrasound scan in the sagittal plane showing a widening of the distal half of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius due a longitudinal mid-substance split and tear of the tendon widening distally to the musculo-tendinous junction. The surrounding muscle and soft tissues are normal.

Figure 4.

Ultrasound scan in the axial plane demonstrating organising haematoma within the centre of a widened and torn distal portion of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius.

Figure 5.

Ultrasound scan in the axial plane demonstrating organising haematoma within the centre of a widened and torn distal portion of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was undertaken on a 1.5 Tesla MR scanner (Phillips Intera 11.1.4). Precontrast axial and sagittal T1 (figs 7–9) and T2 fat suppressed images (figs 10–18) were acquired. Axial T1 weighted images were also obtained (figs 19–23). These were followed by post gadolinium DTPA enhanced T1 fat suppressed axial and sagittal images (figs 24–26).

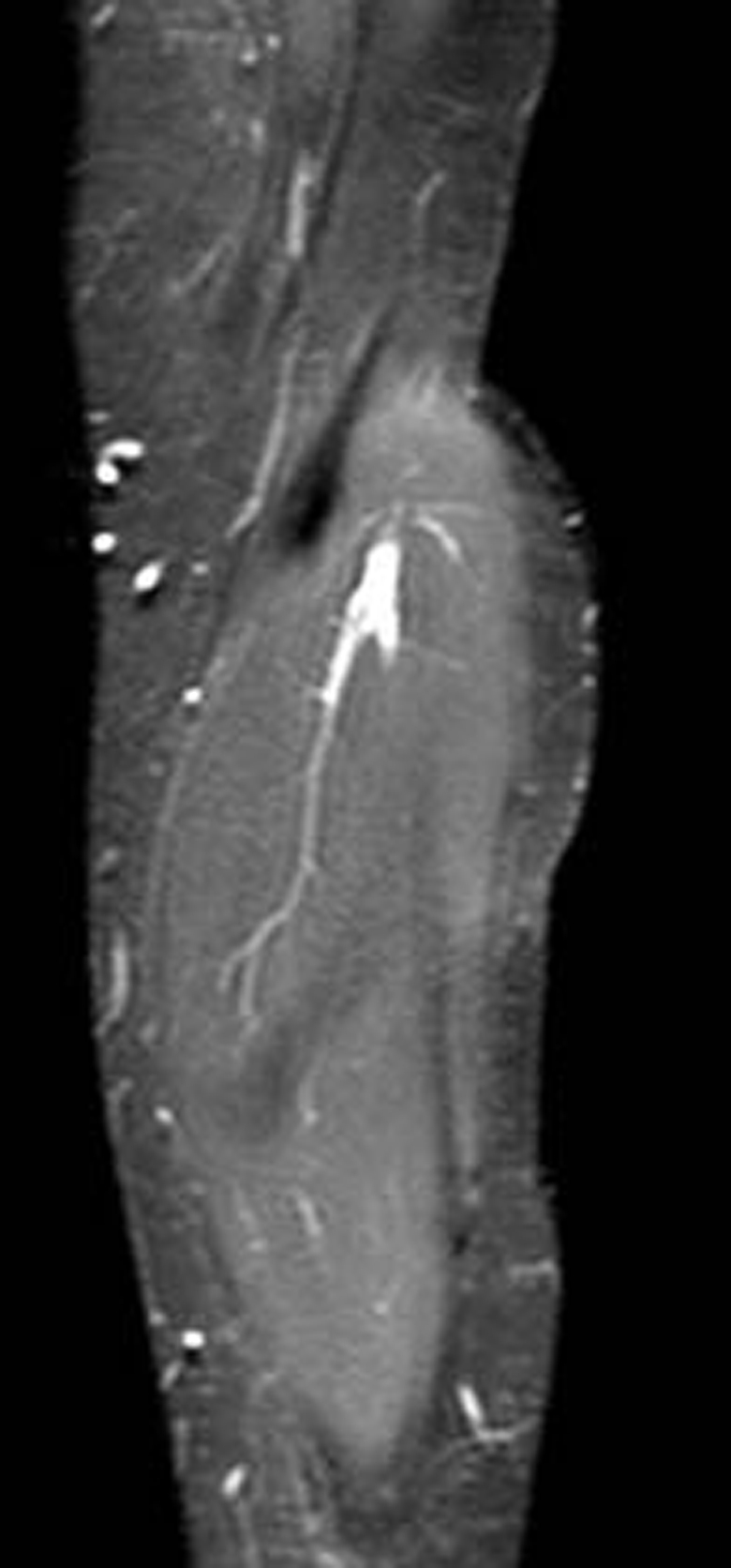

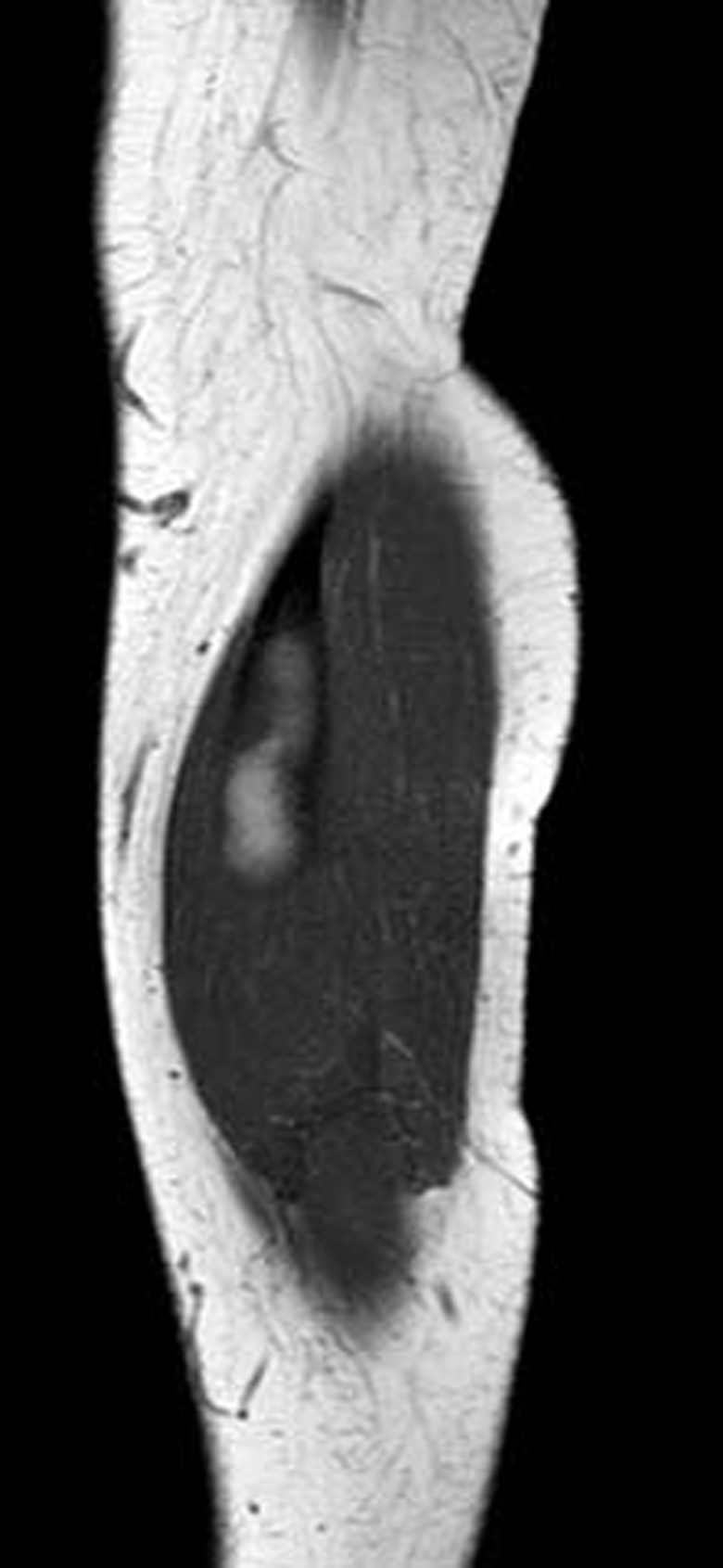

Figure 7.

T1 weighted sagittal MRI scans showing a widened and torn distal portion of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius, haematoma centrally but entirely normal gastrocnemius muscle. The tendon widening is more pronounced distally.

Figure 9.

T1 weighted sagittal MRI scans showing a widened and torn distal portion of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius, haematoma centrally but entirely normal gastrocnemius muscle. The tendon widening is more pronounced distally.

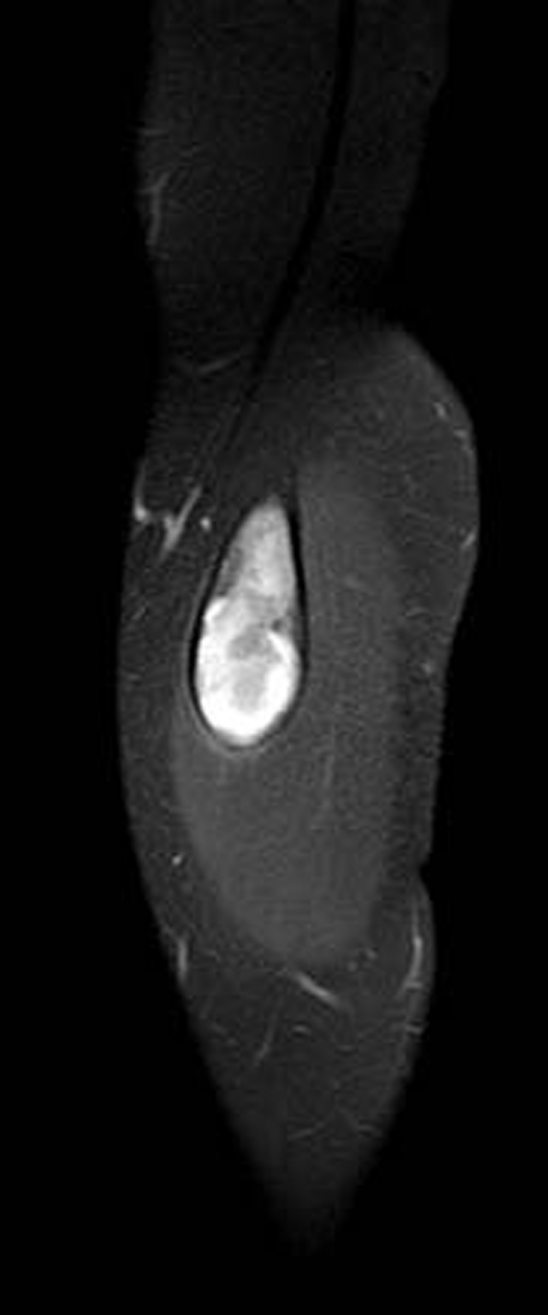

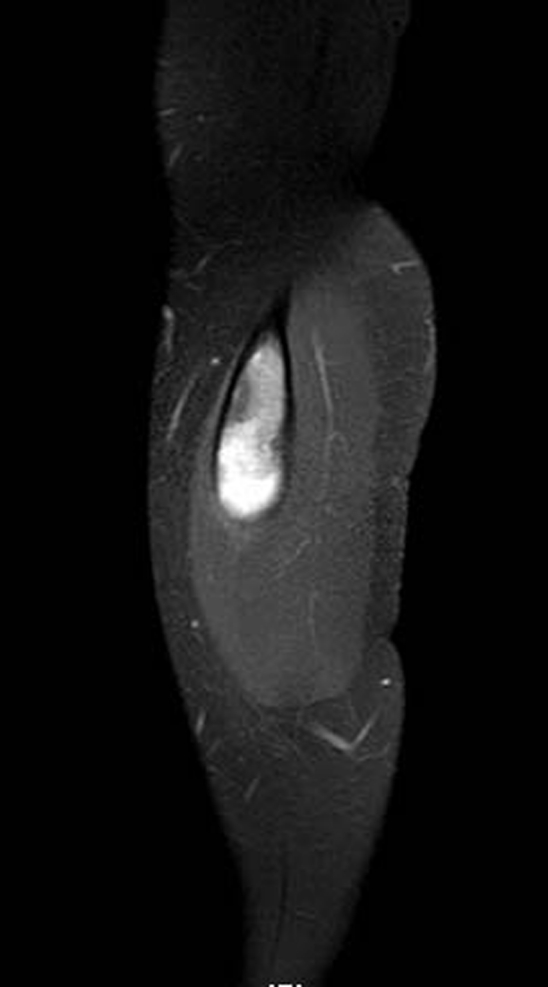

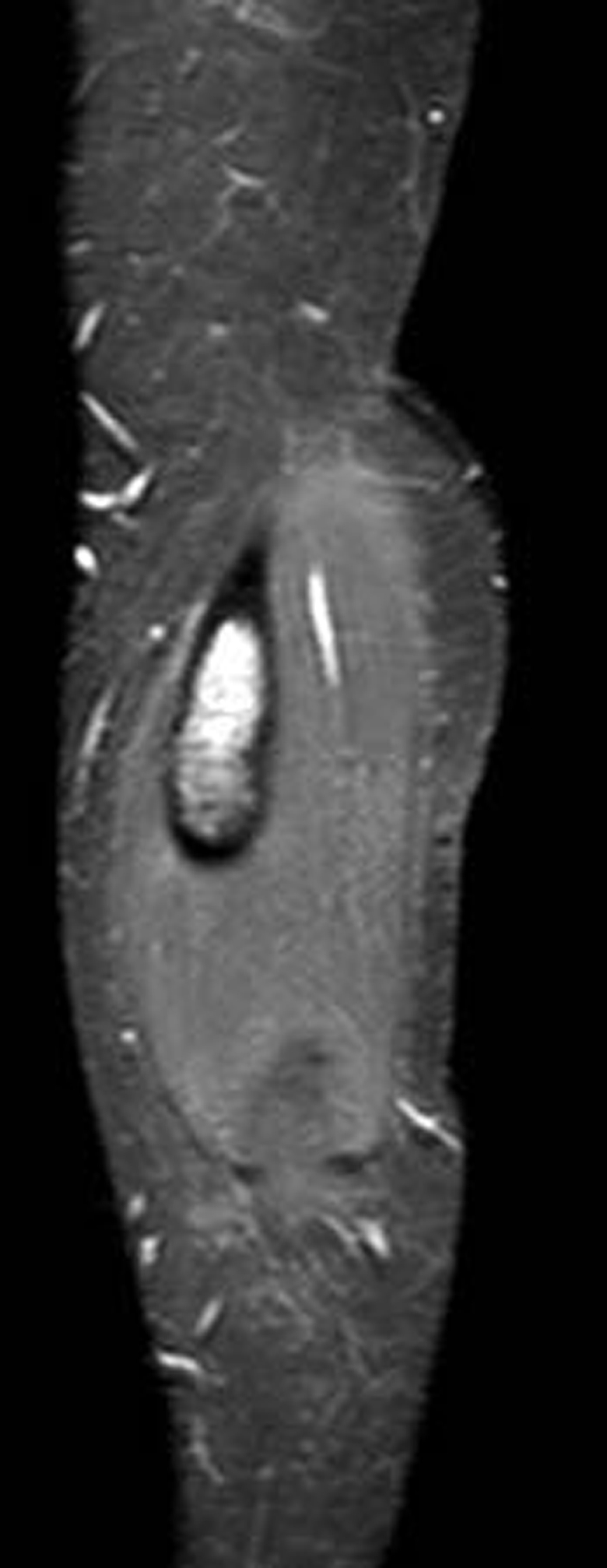

Figure 10.

Fat suppressed MRI images in the sagittal plane showing an isolated tear or split of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius tendon but normal gastrocnemius muscle.

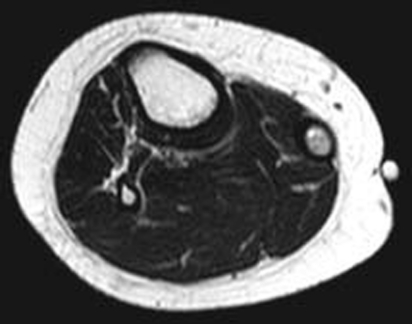

Figure 18.

T2 fat suppressed MRI images of the torn tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius. The scans show progressive rounding and widening of the tendon distally due to a longitudinal split and tear mid-substance. The surrounding muscle (medial head of gastrocnemius) is normal with no tear, inflammation or scarring.

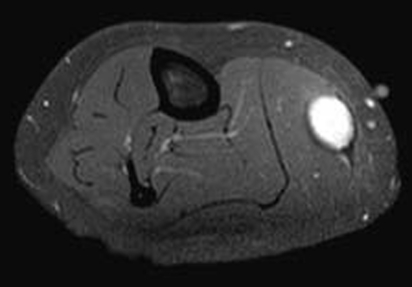

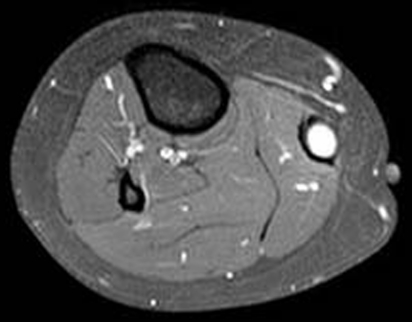

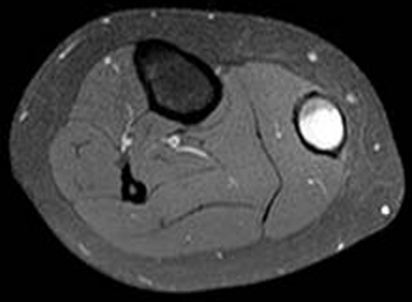

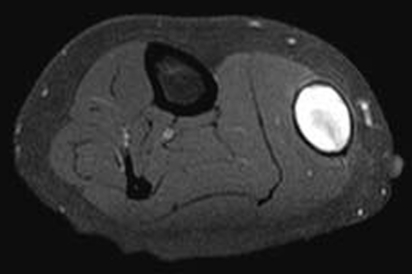

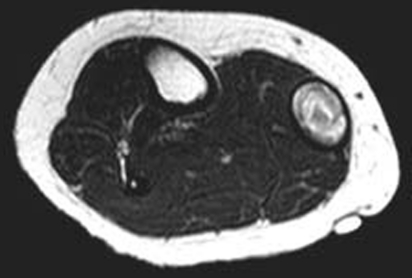

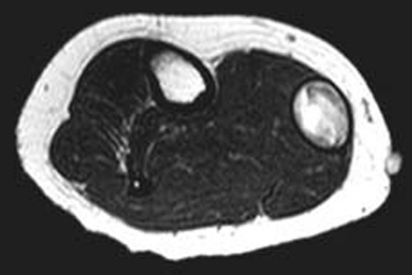

Figure 19.

MRI images in the axial plane showing a tear and widening of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius but no other abnormalities or lesions in the calf.

Figure 23.

MRI images in the axial plane showing a tear and widening of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius but no other abnormalities or lesions in the calf.

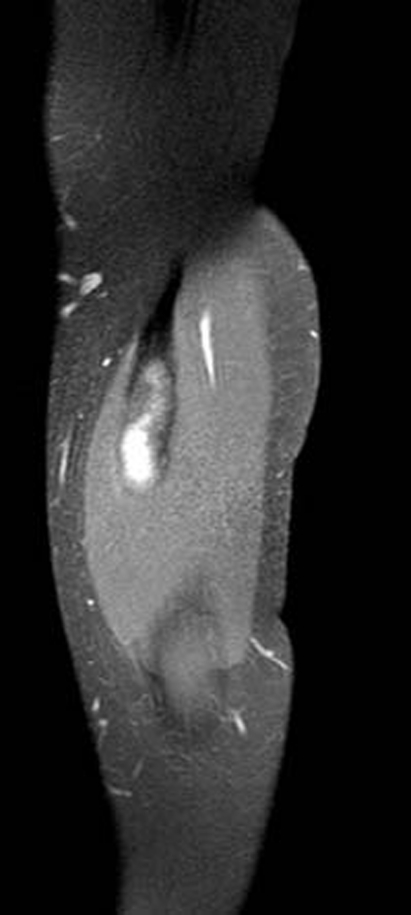

Figure 24.

MRI images acquired in the sagittal plane following intravenous injection of gadolinium DTPA. There is no enhancement following the injection of contrast medium, therefore confirming the absence of active pathology or pathology in the surrounding muscle including inflammation, muscle tear, infection or tumours.

Figure 26.

MRI images acquired in the sagittal plane following intravenous injection of gadolinium DTPA. There is no enhancement following the injection of contrast medium, therefore confirming absence of active pathology or pathology in the surrounding muscle including inflammation, muscle tear, infection or tumours.

Figure 8.

T1 weighted sagittal MRI scans showing a widened and torn distal portion of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius, haematoma centrally but entirely normal gastrocnemius muscle. The tendon widening is more pronounced distally.

Figure 11.

Fat suppressed MRI images in the sagittal plane showing an isolated tear or split of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius tendon but normal gastrocnemius muscle.

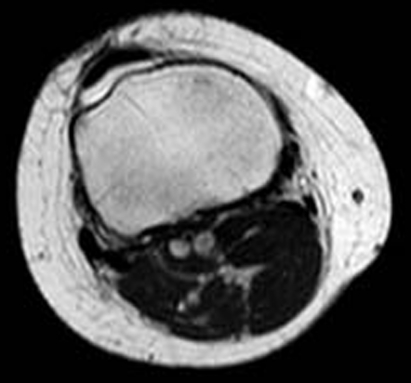

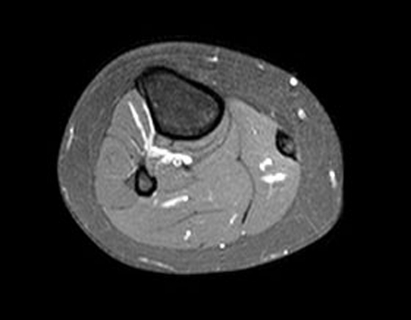

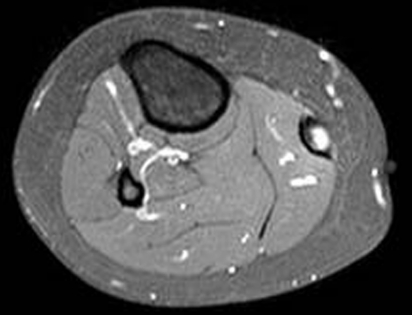

Figure 12.

T2 fat suppressed MRI images of the torn tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius. The scans show progressive rounding and widening of the tendon distally due to a longitudinal split and tear mid-substance. The surrounding muscle (medial head of gastrocnemius) is normal with no tear, inflammation or scarring.

Figure 13.

T2 fat suppressed MRI images of the torn tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius. The scans show progressive rounding and widening of the tendon distally due to a longitudinal split and tear mid-substance. The surrounding muscle (medial head of gastrocnemius) is normal with no tear, inflammation or scarring.

Figure 14.

T2 fat suppressed MRI images of the torn tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius. The scans show progressive rounding and widening of the tendon distally due to a longitudinal split and tear mid-substance. The surrounding muscle (medial head of gastrocnemius) is normal with no tear, inflammation or scarring.

Figure 15.

T2 fat suppressed MRI images of the torn tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius. The scans show progressive rounding and widening of the tendon distally due to a longitudinal split and tear mid-substance. The surrounding muscle (medial head of gastrocnemius) is normal with no tear, inflammation or scarring.

Figure 16.

T2 fat suppressed MRI images of the torn tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius. The scans show progressive rounding and widening of the tendon distally due to a longitudinal split and tear mid-substance. The surrounding muscle (medial head of gastrocnemius) is normal with no tear, inflammation or scarring.

Figure 17.

T2 fat suppressed MRI images of the torn tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius. The scans show progressive rounding and widening of the tendon distally due to a longitudinal split and tear mid-substance. The surrounding muscle (medial head of gastrocnemius) is normal with no tear, inflammation or scarring.

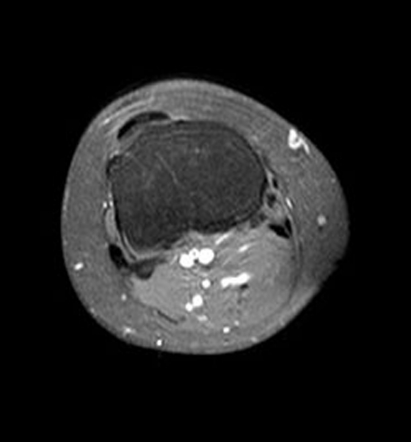

Figure 20.

MRI images in the axial plane showing a tear and widening of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius but no other abnormalities or lesions in the calf.

Figure 21.

MRI images in the axial plane showing a tear and widening of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius but no other abnormalities or lesions in the calf.

Figure 22.

MRI images in the axial plane showing a tear and widening of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius but no other abnormalities or lesions in the calf.

Figure 25.

MRI images acquired in the sagittal plane following intravenous injection of gadolinium DTPA. There is no enhancement following the injection of contrast medium, therefore confirming absence of active pathology or pathology in the surrounding muscle including inflammation, muscle tear, infection or tumours.

The MRI scan was reported as showing a mid-substance split of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius. The tendon was widened to approximately 4 cm with its thin outer rim remaining intact and surrounding a large organising haematoma. The medial head of gastrocnemius muscle was normal as were all the remaining structures of the calf. Of particular note, the myotendinous junction was normal. There was no enhancement following gadolinium injection. The appearances were consistent with an isolated tear of the medial head of gastrocnemius tendon only.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnoses considered clinically for the painless lump included soft tissue malignancy such as sarcoma, benign soft tissue mass such as lipoma or haematoma, muscle hernia and vascular malformation or aneurysm.

TREATMENT

The patient was managed conservatively. She was not advised to stop exercise such as jogging, which she manages although she reports a mild ache localised to the torn tendon area following such activity.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient has been followed up with clinic review and repeat ultrasound imaging. No change in the lesion was reported up to 6 months following initial orthopaedic clinic consultation. She remains active and was pain free until 9 February 2009 when she complained of acute localised pain and bruising in the right calf. This occurred in the preceding week after a long and strenuous walk in the snow during house visits to patients. The pain was followed by a localised spot of tenderness on the medial aspect of the torn tendon at mid part. This has persisted at 2 weeks following the episode. The bruising resolved completely. Ultrasound on 16 February 2009 did not show a significant change to the size or shape of the tendon tear but demonstrated a possible small localised breach of the medial wall of the tendon.

DISCUSSION

The commonly described medial calf injury or “tennis leg” occurs following tear of the medial head of gastrocnemius muscle.1–5 There is avulsion of all or part of the medial head of gastrocnemius from its myotendinous junction.4 This is due to an eccentric force being applied to the gastrocnemius muscle when the knee is extended and the ankle is dorsiflexed. The gastrocnemius muscle attempts to contract in the already lengthened state leading to tear of the muscle.3,4 The classical clinical history of a calf strain is that of a sharp tearing or popping sensation during physical activity, occurring usually when the calf muscles are stretched simultaneously over the ankle and knee joint (that is, in dorsiflexion and extension, respectively). Clinically there is marked decrease in plantar flexion strength. Swelling or ecchymosis may be visible. Rarely the swelling may be so extensive that it causes an acute compartment syndrome.1,6,7 Several theories were previously suggested as to the underlying nature of “tennis leg” including the suggestion that it may be due to tear of the plantaris muscle.8,9 It is now accepted that the injury is due to tear or rupture of the medial head of gastrocnemius muscle.1–4 Delgado et al retrospectively evaluated ultrasound findings in 141 patients with a classic diagnosis of tennis leg to determine the relative involvement of the plantaris tendon and gastrocnemius muscle in the pathogenesis of the condition.10 Partial rupture of the gastrocnemius muscle without rupture of the plantaris tendon was identified in 66.7% of patients. Of these, 62.8% had associated fluid collection between the medial head of gastrocnemius muscle and the soleus muscle. Fluid collection between the aponeuroses of the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles without evidence of rupture of the triceps surae was found in 21.3%. Partial rupture of the soleus muscle was seen in 0.7%. Isolated deep vein thrombosis occurred in 9.9%. Rupture of the plantaris tendon was seen in two patients (1.4%). The authors concluded that rupture of the medial head of gastrocnemius muscle was more common than that of the plantaris tendon and soleus muscle.10 There were no tears reported of the tendon to the medial head of gastrocnemius muscle. We have found no such reports in the literature and no reports of isolated split or partial tear of the medial head of gastrocnemius tendon. There are also no published descriptions of tennis leg or gastrocnemius muscle tear leading to an intra-substance tear of the tendon to medial head of gastrocnemius acutely or as a long-term consequence. The imaging carried out on our patient showed no evidence that there had ever been any muscle tear, and the medial head of gastrocnemius muscle and the myotendinous junction were normal with no scarring or acute tear present. Our findings are important having shown pathology not previously described in the calf. The possibility of an isolated tear of the medial head of gastrocnemius tendon should therefore be considered in a patient presenting with a painless lump in the medial upper calf even in the absence of a history of trauma. The absence of a history of trauma in our patient raises the possibility that an isolated medial head of gastrocnemius tendon tear may occur as a “silent” injury or with little pain. We recommend ultrasound and MRI as the investigations of choice. These imaging modalities can confirm the diagnosis but also exclude other pathology such as soft tissue tumours, cystic lesion (for example meniscal cyst), popliteal artery aneurysm and deep vein thrombosis.

LEARNING POINTS

Isolated tear of the medial head of gastrocnemius tendon should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a lump in the medial upper aspect of the calf (overlying the medial head of gastrocnemius muscle) even in the absence of pain or a history of trauma.

The appropriate investigations should include ultrasound and/or magnetic resonance imaging.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koulouris G, Ting AY, Jhamb A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of injuries to the calf muscle complex. Skeletal Radiol 2007; 36: 921–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrett WE., Jnr Muscle strain injuries. Am J Sports Med 1996; 24(6 Suppl): S2–S8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller WA. Rupture of the musculotendinous juncture of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle. Am J Sports Med 1977; 5: 191–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert TJ, Bullis BR, Griffiths HJ. Tennis calf or tennis leg. Orthopaedics 1996; 19: 179–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Severance HJ, Bassett FH., III Rupture of the plantaris: does it exist? J Bone Joint Surg Am 1982; 64: 1387–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohanna PN, Haddad FS. Acute compartment syndrome following non-contact football injury. Br J Sports Med 1997; 31: 254–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarolem KL, Wolisky PR, Savenor A, et al. Tennis leg leading to acute compartment syndrome. Orthopaedics 1994; 17: 721–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powel RW. Lawn tennis leg. Lancet 1883; 2: 44 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helms CA, Fritz RC, Garvin GJ. Plantaris muscle injury: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology 1995; 195: 201–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delgado GJ, Chung CB, Lektrakul N, et al. Tennis leg: clinical US study of 141 patients and anatomic investigation of four cadavers with MRI imaging and US. Radiology 2002; 224: 112–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]