Abstract

Superimposed infection of osteoradionecrotic cervical spine with cranial extension is difficult to treat and potentially fatal. This report describes the case of a middle-aged Chinese man 11 years post radical radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal cancer with no evidence of disease presenting initially with neck pain secondary to cervical osteoradionecrosis. He was re-admitted a month later with aspiration pneumonia associated with Streptococcus milleri bacteraemia, complicated by septic shock. The last re-admission was 2 months later with fever, expressive dysphasia and right upper motor neuron signs. There was interval increase of dental and peridental soft tissue mass, interval widening of atlantodental distance on MRI cervical spine associated with pneumocephalus, meningeal enhancement and pre-pontine soft tissue mass on CT brain consistent with infected osteoradionecrotic cervical spine complicated by cranial extension. The patient also had concomitant bilateral pneumonia and subsequently passed away from fulminant sepsis.

BACKGROUND

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a common head and neck malignancy in the Chinese. NPC is a highly radiosensitive malignancy. Early stage NPC is treated with radiotherapy alone, with a 5-year survival of >80%.1 However, patients can present years later disease free with debilitating late complications of radiotherapy including osteoradionecrosis, hypothyroidism, panhypopituitarism, oropharyngeal dysfunction, radiation-induced tumour and/or mixed type hearing loss.2

Osteoradionecrosis is an uncommon late complication of radiotherapy. It can present insidiously and progress rapidly, especially in the setting of superimposed osteomyelitis. Osteoradionecrosis of the 1st and 2nd cervical vertebrae post treatment for primary head and neck cancer was first reported in 19993 and there was another case subsequently reported by Donovan et al.4 To our knowledge, this is the third reported case of 1st and 2nd cervical spine osteoradionecrosis in the literature post therapy for primary head and neck cancers. The aim of this case report is to highlight two issues. The first is that C1/C2 bone destruction in this particular case is secondary to osteoradionecrosis and not NPC. Second, there are challenges in recognising and managing osteoradionecrosis and its associated complications in head and neck cancer patients previously treated with radiotherapy, especially at a relatively inaccessible site in close proximation to vital structures.

We report a case of a middle-aged Chinese man with past history of stage II NPC presenting 11 years post radical radiotherapy with osteoradionecrosis of cervical spine. He had co-existing radiotherapy related oropharyngeal dysfunction complicated by aspiration pneumonia with Streptococcus milleri bacteraemia. There was likely to be superimposed infection of osteoradionecrotic bone complicated by cranial extension with pneumocephalus, meningitis and subsequently death.

CASE PRESENTATION

A middle-aged Chinese man with T2N1M0 (Ho’s staging) NPC involving the paranasopharynx with a right retropharyngeal lymph node and bilateral cervical lymph node involvement was treated with radical radiotherapy in 1997.

He received external beam radiotherapy 66 Gy in 33 fractions to the nasopharynx, 60 Gy in 30 fractions to the neck, followed by two intracavity brachy therapy insertions at weekly intervals at 5 Gy per fraction over 2 weeks to boost the dose in the nasopharynx.

Previous medical history included tuberculosis (treated) and cervical spondylosis.

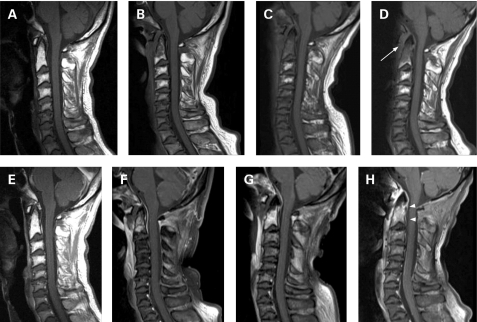

He presented initially with a 1-month history of severe mechanical neck pain associated with decreased range of neck movement. Cervical spine radiographs reveal cervical spondylosis most marked at the C5–C6 level with no overt bony destruction (fig 1). A repeat cervical spine MRI during his initial presentation showed an interval development of enhancing soft tissue mass within the dens and another enhancing pre-vertebral soft tissue when compared with a previous MRI performed 6 years earlier. There was also concomitant widening of the atlantodental space to 4 mm. These radiological features were suspicious for osteoradionecrosis of the upper cervical spine with the possibility of a superimposed infection (fig 2A, B, F, G). However, he was clinically non-toxic. He responded to symptomatic treatment with analgesia.

Figure 1.

Lateral radiograph of the cervical spine done 3 months before the last admission showing cervical spondylosis, worse at the C5–C6 level, with no overt bony destruction.

Figure 2.

Selected sagittal T1 weighted pre-contrast MRI images of the cervical spine done (A) 6 years before, (B) 3 months before, (C) 2 months before and (D) during the last admission. T1 weighted post-contrast sequences (E–H) are shown below their corresponding pre-contrast images. Post-radiation fatty replacement is noted from C1 down to C5, most appreciable in (A), the T1 weighted pre-contrast image done 6 years ago. On follow-up MRI studies from 3 months ago to the last admission (B–D, F–H), there is development of enhancing soft tissue mass within the dens, eventually involving the entire dens and the C2 vertebral body during the current admission (white arrowhead). This enhancing soft tissue is also seen to extend down the pre-vertebral space to the level of C5. The atlantodental distance is seen to increase from (A) a normal 2 mm 6 years ago, (B) to a mildly widened 4 mm 3 months before, and (D) to finally measure 8 mm in the last admission (white arrow).

He was treated a month later for aspiration pneumonia and S milleri bacteraemia complicated by septic shock requiring admission to the intensive care unit. A repeat MRI of the cervical spine during the same admission was consistent with worsening osteoradionecrosis with interval increase in the atlantodental distance to 6 mm. (fig 2C, G) He was treated with 6 weeks of intravenous crystalline penicillin and was subsequently given long-term clindamycin therapy for presumed secondary osteomyelitis.

He was re-admitted 2 months later, presenting with fever initially treated with oral amoxicillin/clavulanate. However, 2 days later, he was acutely confused with associated expressive dysphasia, right facial droop, right-sided hypertonia and hyper-reflexia. He was switched to intravenous pipercillin/tazobactum for sepsis. An urgent CT brain revealed extensive pneumocephalus with leptomeningeal enhancement suggestive also of meningitis. (fig 3) This was confirmed on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis post antibiotic therapy; this showed active chronic inflammatory exudate. An acid-fast bacillus smear was negative. CSF fluid cultures were not available and blood cultures were negative.

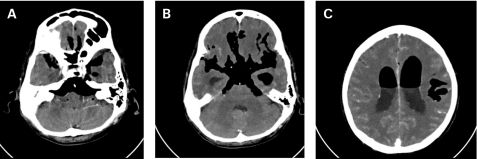

Figure 3.

Axial post-contrast CT images showing marked pneumocephalus suspicious for either a breech of the subarachnoid space secondary to the changes in the craniocervical region or be secondary to a gas-forming infection.

Another MRI brain done during the same admission showed interval extension of the enhancing soft tissue that now involved the entire dens and C2 vertebral body. There was also interval extension of the pre-vertebral soft tissue down to the C5 level with progression of the atlantodental space widening to 8 mm (fig 2D, H). There was also new enhancing soft tissue now occupying the pre-pontine cistern and surrounding the basilar artery (fig 3). Features were compatible with worsening superimposed osteomyelitis of the osteoradionecrotic cervical spine with cranial extension.

Figure 4.

Axial T1 weighted post-contrast image at the level of the brainstem shows an enhancing soft tissue occupying the pre-pontine cistern and surrounding the basilar artery.

The patient also developed concurrent bilateral pneumonia secondary to aspiration.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

At the time of initial presentation, there was interval development of enhancing dental soft tissue mass, pre-vertebral soft tissue enhancement and a slight increase in the atlantodental spaces to 4 mm suggestive of superimposed spontaneous infection of the osteonecrotic bone. However, the patient remained clinically non-toxic and was managed conservatively. Other differentials included reactivation of latent tuberculosis in view of his past medical history.

Since then there had been interval progression of the osteomyelitis, which could be progressive from the underlying infective process or it could have been potential seeding of S milleri to the osteoradionecrotic dens from his aspiration pneumonia with S milleri bacteraemia.

The patient subsequently also developed pneumocephalus with meningitis. This is due to: (a) a fistulous connection to the subarachnoid space from cranial extension of the cervical spine osteomyelitis, (b) new development of a gas-forming infection, or (c) cancer recurrence with a fistulous connection between the nasopharynx and the CSF space. The first differential is most likely for reasons discussed below.

The presence of peridental soft tissue mass with craniocaudal extension confirmed radiologically on MRI and CT as discussed above is highly suggestive of progressive cervical spine osteomyelitis with abscess formation and likely fistula development from the aerodigestive tract to the subarachnoid space not demonstrated on the MRI.

The presentation of this patient’s illness was subacute, which is peculiar to that of a gas-forming infection.

Radiologically, there was no evidence of cancer recurrence, or clinically on a nasopharyngoscope performed during a recent follow-up assessment. In addition, it would be unusual for a rapidly growing recurrent cancer to occur at the base of skull without destruction of the surrounding structures.

TREATMENT

Treatment for this patient remained largely medical with the use of intravenous antibiotics. During his last admission, his infection was extensive extending up to the pre-pontine cistern with co-existing bilateral pneumonia making him a poor candidate for any surgical intervention. The use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in such a candidate was unclear and not instituted.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

He failed to respond to further escalation of antibiotics (meropenem and vancomycin) and he passed away 5 days later from meningitis and pneumonia.

DISCUSSION

Osteoradionecrosis (ORN) is a well-recognised late complication of radiotherapy. Following irradiation of head and neck cancers, osteoradionecrosis of the mandible has been more commonly reported with an incidence of 8.2%.5 The following bones: mandible, frontal bone, cervical spine, maxilla, temporal and nasal bones, have been reported to be affected in descending order of frequency.6 The exact incidence of ORN of skull base or cervical spine is unclear.

Importantly, osteoradionecrotic sites are potentially structurally unstable resulting in pain syndromes either musculoskeletal or neuropathic. They are also potential niduses for occult infection and abscess formation.

Lim et al reported the first case of 1st and 2nd cervical vertebrae ORN in a 60-year-old patient 9 years post treatment succumbing to ORN complicated by retropharyngeal abscess and concurrent pneumonia requiring intubation.3 Donovan et al presented a 71-year-old patient 10 years post radiotherapy for NPC with 1st and 2nd cervical vertebrae osteoradionecrosis responding to hyperbaric oxygen therapy alone in the absence of superimposed infection and spinal instability.4 These reports described two contrasting cases with very different outcomes, illustrating the severity of superimposed infection on osteoradionecrotic bone, as again highlighted by our report.

Recommended treatments for ORN include surgery to debride the necrotic tissue and/or adjuvant hyperbaric oxygen therapy to improve vascularity of the radiation damaged tissue7,8 However, due to the site and location of the disease in our patient at the base of skull region, any surgical intervention carried a substantial morbidity and mortality risks; hence, management was conservative from the start focusing on symptom control with analgesia and antibiotics. Despite antibiotic therapy, the infection progressed with pre-pontine cistern involvement further limiting access to meaningful surgical debridement, especially in the setting of overwhelming sepsis including pneumonia. The use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in osteoradionecrosis is often as an adjunct and its clinical efficacy is controversial9–11 The optimal management in this setting remained the use of intravenous antibiotics.

Radiotherapy though an important and effective mode of curative treatment in early stage head and neck malignancies is not without its own risks. Even in the setting of careful consideration prior to radiotherapy for NPCs, with choice of radiation doses within safe limits (eg, <60 Gy to neck) to reduce complication rates and subsequent regular surveillance, late complications with adverse sequelae still occur. Management of osteoradionecrosis of the 1st and 2nd cervical spine is challenging and limited by surgical accessibility. Superimposed infection in severe osteoradionecrosis confers adverse prognosis and increases the risk of mortality.

LEARNING POINTS

Radiotherapy is a useful treatment modality for primary head and neck cancers.

Careful planning pre-radiotherapy is warranted to avoid multiple debilitating late complications that arise and often co-exist; nevertheless, complications may still arise.

C1/C2 bony destruction in a patient with previous nasopharyngeal cancer is not necessarily related to underlying cancer. In the present case, it is treatment related, secondary to osteoradionecrosis.

Osteoradionecrosis is an uncommon late complication post radiotherapy with insidious presentation and rapid progress. It is better prevented than treated. It should be screened for clinically and should be considered in someone with musculoskeletal symptoms in a region previously irradiated.

Osteoradionecrotic bone is unhealthy tissue prone to secondary osteomyelitis, which is often spontaneous.

Superimposed infection in osteoradionecrotic bone, especially in the 1st and 2nd cervical vertebrae with abscess formation is potentially fatal.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee AW, Sze WM, Au JS, et al. Treatment results for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the modern era: the Hong Kong experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005; 61: 1107–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King AD, Ahuja AT, Yeung DK, et al. Delayed complications of radiotherapy treatment for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: imaging findings. Clin Radiol 2007; 62: 195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim AA, Karakla DW, Watkins DV. Osteoradionecrosis of the cervical vertebrae and occipital bone: a case report and brief review of the literature. Am J Otorlaryngol 1999; 20: 408–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donovan DJ, Huynh TV, Purdom EB, et al. Osteoradionecrosis of the cervical spine resulting from radiotherapy for primary head and neck malignancies: operative and nonoperative management. Case report. J Neurosurg Spine 2005; 3: 159–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reuther T, Schuster T, Mende U, et al. Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws as a side effect of radiotherapy of head and neck tumour patients – a report of a thirty year retrospective review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003; 32: 289–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prasad KC, Prasad SC, Mouli N, et al. Osteomyelitis in the head and neck. Acta Otolaryngol 2007; 127: 194–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vissink A, Burlage FR, Spijkervet FK, et al. Prevention and treatment of the consequences of head and neck radiotherapy. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2003; 14: 213–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hao SP, Hung CC, Wei FC, et al. Systematic management of osteoradionecrosis in the head and neck. Laryngoscope 1999; 109: 1324–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annane D, Depondt J, Aubert P, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for radionecrosis of the jaw: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial from the ORN96 study group. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 4893–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldmeier JJ. Hyperbaric oxygen for delayed radiation injuries. Undersea Hyperb Med 2004; 31: 133–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bui QC, Lieber M, Withers HR, et al. The efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of radiation-induced late side effects. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004; 60: 871–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]