Abstract

Drug-induced cholangiohepatitis accounts for 20–50% of non-viral chronic hepatitis cases. Metformin is the most commonly prescribed oral anti-diabetic drug from the biguanide class used in treatment of overweight and obese type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Metformin-induced cholangiohepatitis with marked elevations in serum liver transaminases and intrahepatic cholestasis has been infrequently reported. Here, we report a case of acute cholangiohepatitis after initiation of metformin treatment.

BACKGROUND

This case highlights the presentation of drug-induced cholangiohepatitis due to a commonly prescribed medication. Drug-induced cholangiohepatitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with right upper quadrant abdominal pain and liver enzyme abnormalities.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 61-year old male presented with complaints of fever, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and jaundice of 4 days duration. Past medical history is significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, coronary artery disease and gout. He does not smoke, drink alcohol and denies any recreational drug use or over the counter drug use. Four weeks prior to the onset of symptoms, metformin (500 mg oral twice a day) was added to his drug regimen, which also includes aspirin, glyburide and allopurinol.

INVESTIGATIONS

Physical examination was remarkable for a temperature of 101 degrees Fahrenheit and right upper quadrant tenderness. No skin rash was noted. Laboratory studies revealed white cell count of 20.0 K/Cu MM with 87% neutrophils, haemoglobin of 15.5 gm/dL, haematocrit of 45.7% and platelets of 322 K/Cu MM with no peripheral eosinophilia. Total protein of 6.9 mg/dL with albumin 4.4 mg/dL, total bilirubin 2.6 mg/dL (normal 0.2–1.2 mg/dL), direct bilirubin 1.2 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 22 IU/L (15–59), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 16 IU/L (21–72) and alkaline phosphate 102 IU/L (36–125). Amylase and lipase were normal. The patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics for a possible acute cholecystitis. Home medications were held and insulin protocol was initiated.

On the second hospital day, white cell count improved and fevers resolved. However, AST increased to 38 IU/L, ALT to 169 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase to 437 IU/L and total bilirubin to 4.2 mg/dL. Liver ultrasound revealed mildly distended gall bladder with sludge, moderate gallbladder wall thickening without calculi or liver mass and evidence of biliary ductal dilation. Endoscopic retrograde cholecysto-pancreatography (ERCP) with papillotomy was performed on the third hospital day. ERCP revealed normal pancreatic and common bile duct. The filling of biliary ductal system, including intrahepatic, cystic and gallbladder, was unremarkable. No stones or sludge were identified. Fever resolved and so the antibiotics were discontinued.

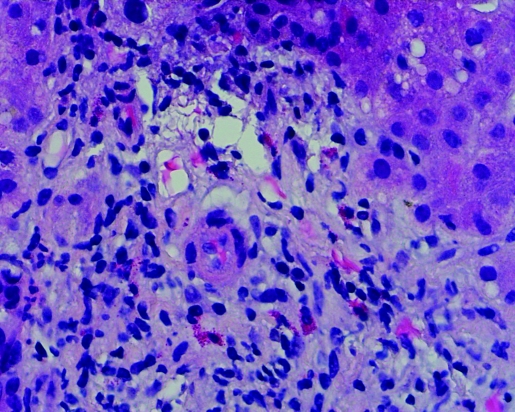

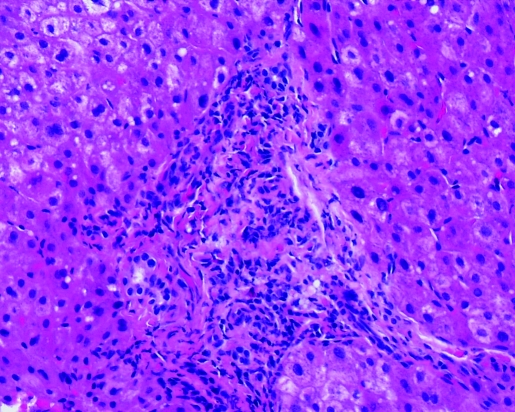

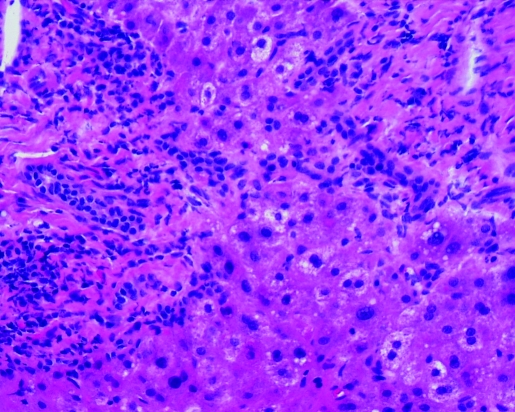

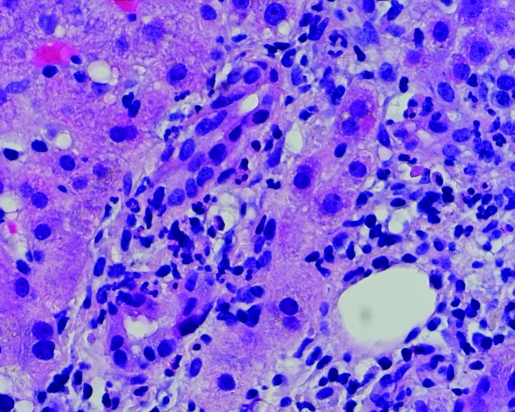

Post-ERCP total bilirubin level and alkaline phosphatase remained elevated. ALT returned to the normal range. Hepatitis A, B and C serologies were negative. Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) was <7.5 IU/ml (<7.5 IU/ml); anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA) 10 units (0–19 units) and alpha-1 antitrypsin 142 mg/dL (90–200 mg/dL). Percutaneous liver biopsy was performed, which revealed portal tracts with mixed inflammatory infiltrate characterised by neutrophils, lymphocytes and abundant eosinophils (figs 1 and 2). Acute inflammatory cells were seen infiltrating bile ductules with epithelial disruption and compensatory ductular proliferation (fig 3). The process was accompanied with mild spill-over into the surrounding zone-II hepatic parenchyma (fig 4). The histopathological findings were compatible with mild subacute cholangitis.

Figure 1.

Portal triaditis with abundant eosinophils (400×).

Figure 2.

Portal triaditis with intraepithelial neutrophils (400×).

Figure 3.

Bile ductular proliferation (200×).

Figure 4.

Portal triaditis with spill-over across the limiting plate (200×).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The presence of abundant eosinophils in the liver biopsy specimen raised the possibility of medication-induced cholangiohepatitis. Metformin was the only new addition to the patient’s chronic medication regimen and was rightly discontinued. Patient’s symptoms were completely resolved and he was discharged home. Blood tests done 4 weeks after discontinuing metformin revealed normal bilirubin (0.9 mg/dL), AST (23 IU/L) and ALT (24 IU/L) levels. Alkaline phosphatase remained slightly elevated at 185 IU/L.

Subsequently, the patient underwent an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy with repeat liver biopsy. Surgical specimen of gall bladder revealed subacute and chronic cholecystitis with adhesions. Liver biopsy showed moderate chronic portal triaditis with piecemeal necrosis and grade II/stage II fibrotic changes consistent with residual medication effect.

DISCUSSION

Metformin is the most commonly used anti-hyperglycaemic in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus.1 Metformin is thought to increase insulin sensitivity by simultaneously decreasing hepatic glucose production and increasing glucose transport across skeletal muscle membrane.1,2 The exact mechanism through which metformin effects hepatic gluconeogenesis is unclear. However, it seems to disrupt respiratory chain oxidation of complex I substrates like glutamate at mitochondrial level resulting in decreased gluconeogenesis and enhancing glucose utilisation via induction of glucose transporters.2

Metformin is not metabolised in the liver and is excreted unchanged in the urine.2 The gastrointestinal side effects associated with metformin use includes diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, bloating and flatulence.3 Lactic acidosis can occur especially in renal failure patients3 and on long-term use can cause reduction in folic acid and vitamin B12 levels.3 Metformin-induced cholangiohepatitis with marked elevations in serum liver transaminases and intrahepatic cholestasis has been infrequently reported.3–7

Drug-induced cholangiohepatitis accounts for 20–50% of non-viral chronic hepatitis cases and, therefore, should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with right upper quadrant pain and liver enzyme abnormalities.4 Rarely acute, drug-induced ductular cholestasis can present as biliary tract obstruction.5 Prompt withdrawal of the causative drug usually leads to complete recovery. Other drugs implicated in cholangiohepatitis with intrahepatic cholestasis include hormonal steroids, psychopharmacological agents such as phenothiazines and some antidepressants, phenobarbital and D-pencillamine.5 Hepatic eosinophilia can be seen with helminthic parasite infections such as schistosomiasis, toxocariasis and clonorchiasis. Other aetiologies to consider are primary biliary cirrhosis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, sclerosing cholangitis, eosinophilic cholangitis and eosinophilic cholecystitis.

This case highlights the presentation of drug-induced cholangiohepatitis due to a commonly prescribed medication. The temporal association of patient’s symptoms and liver enzyme abnormalities with medication use, hepatic eosinophilia on biopsy and a “Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) Probability Scale” score of 5 clearly suggests the probability of metformin-induced cholangiohepatitis.8 Understanding drug-induced liver injury and timely withdrawal is critical to avoid unnecessary invasive evaluation and intervene before irreversible injury is established.9

LEARNING POINTS

This case highlights the presentation of drug-induced cholangiohepatitis due to a commonly prescribed medication.

Eosinophils present on liver biopsy should make us think of medication-induced cholangiohepatitis.

Drug-induced cholangiohepatitis, which accounts for 20–50% of non-viral chronic hepatitis cases, should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with right upper quadrant pain with liver enzyme abnormalities.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wood AJJ, Bailey CJ, Turner RC. Metformin. NEJM 1996; 334: 574–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirpichnikov D, McFarlane SI, Sowers JR: Metformin: an update. Ann Int Med 2002; 137: 25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desilets DJ, Shorr AF, Moran KA, et al. Cholestatic jaundice associated with the use of metformin. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 2257–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nammour FE, Fayad NF, Peikin SR. Metformin-induced cholestatic hepatitis. Endocrine Practice 2003; 9: 307–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baillieres Drug-induced cholestasis. Clin Gastroenterol 1988; 2: 423–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babich MM, Pike I, Shiffman ML. Metformin-induced acute hepatitis. Am J Med 1998; 104: 490–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kutoh E. Possible metformin-induced hepatotoxicity. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2005; 3: 270–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clinical Pharmacol Ther 1981; 30: 239–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chitturi S, Farrell GC. Drug-induced cholestasis. Sem Gastrointestinal Disease 2001; 12: 113–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]