Abstract

We report a case of paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) as an uncommon but severe cause of cicatrising conjunctivitis. Initially diagnosed as drug eruptions, the patient’s condition did not improve despite cessation of chemotherapy. Immunohistological confirmation of PNP has led to the use of combined oral prednisolone and intravenous immunoglobulin. Her ocular conditions stabilised with complete recovery of vision. PNP is a rare disease that can present with ocular involvement. Ophthalmologists should play an active role in monitoring and treatment of ocular surface complications such as symblepharon formation, severe dry eye and epithelial breakdown. Vigorous and prompt treatment is the key to successful prevention of irreversible and blinding complications. The atypical feature in this case is the presence of eosinophilic infiltration on histology that is a feature of allergic aetiologies rather than classical PNP.

Background

Chronic cicatrising conjunctivitis (CCC) denotes a group of disorders that causes conjunctival scarring and fibrosis. Autoimmune diseases including Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP), linear IgA disease and graft versus host disease are common atiologies.1 The ocular consequences in common are impaired ocular mobility, defective tear dynamics; and, in later stages, secondary corneal complications that ultimately threaten corneal transparency.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP)2 is an uncommon disorder that shares overlapping clinical features with SJS3 and immunochemical features with pemphigus vulgaris. Associated malignancy may precede or occur in conjunction with mucocutaneous changes.4 To date, there are no data on the possible trigger for such development. We report a case of bilateral PNP initially diagnosed as drug eruptions which was later revised to PNP on immunochemical grounds.

Case presentation

In July 2007, ophthalmic attention was drawn to the possible ocular involvement in a middle aged woman who suffered from generalised mucocutaneous eruption at the oncology ward of a teaching hospital.

She had a history of stage III follicular lymphoma since 2004; this had been clinically in remission after treatment with rituximab (a chimeric monoclonal antibody to the CD20 antigen) until the beginning of 2007 when there was radiological evidence of progression with extensive lymphomatous infiltration of the cervical, axillary, thoracic, abdominal, pelvic, groin and omental regions. Chemotherapy comprising oral chlorambucil and prednisolone was commenced. Allopurinol, a drug that she had received 3 years ago, was given again to prevent possible tumour lysis syndrome from bulky disease. Five days later, she developed painful mucosal ulceration involving the oral cavity, lips and tongue (fig 1), with sparing of the conjunctiva and genitalia. Cutaneous changes, including non-itching papular rash over four limbs and target lesions over the chest, were also noted (fig 2). There was low grade fever. Differential diagnosis included drug eruptions, SJS, and erythema multiforme.

Figure 1.

Image of the patient’s lips, showing oral mucosal involvement.

Figure 2.

Polymorphous cutaneous eruption, taken from the patient’s forearm (courtesy of the Department of Dermatology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong).

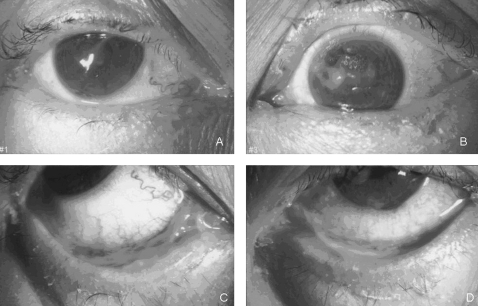

Cessation of systemic chlorambucil and allopurinol did not alleviate the mucocutaneous eruptions. Although oral feeding was tolerated, the patient developed mild intermittent dyspnoea and demanded oxygen via nasal canula. Supportive care consisting of hydration and wound dressing was maintained while awaiting a definitive diagnosis. She developed bilateral conjunctival redness and pain 2 days after admission. Ophthalmic examination revealed visual acuities of 20/30 bilaterally and pressures of 12 and 14 mm Hg over the right and left eyes, respectively. Slit lamp examination showed bilateral pseudomembranous conjunctivitis with early symblepharon formation. There was punctate epithelial erosion on both corneas. Examination of the anterior chamber and dilated fundoscopy were unremarkable. There was no restriction in extraocular movements or lagophthalmos.

Forniceal rodding was performed daily under topical anaesthesia (unpreserved tetracaine 1% eyedrops) to lyse the emerging symblepharon. Necrotic debris was debrided and removed whenever necessary. Treatment with prednisolone acetate 1%, levofloxacin 0.5% eyedrops, and unpreserved paraffin nocturnal ointment (Duratears, Alcon) was commenced. A corneal epithelial defect was noted in the left eye 2 days later with mucous plaque adherent to the exposed area (fig 3). Schirmer’s test under topical anaesthesia showed minimal baseline tear production (0 mm right eye and 1 mm left eye). The patient’s vision dropped to 20/100 bilaterally. Topical lubrication was applied on a hourly basis and bilateral lower lid punctual occlusion was performed.

Figure 3.

Slit lamp images of the patient showing ocular signs. (A) Normal right cornea with surface mucous plaque. (B) Central epithelial defect. (C, D) Inferior fornix pseudomembranous conjunctivitis with symblepharon formation.

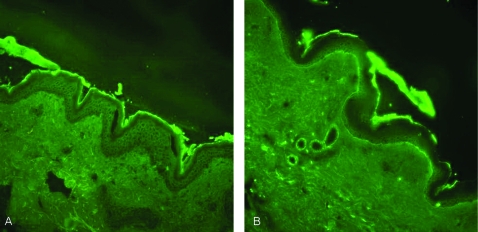

A diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus was made. This was supported by positive skin biopsy taken from the thigh which showed orthokeratosis with subepidermal bulla containing mixed inflammatory cells including eosinophils and neutrophils (fig 4). Some acantholytic cells were seen at the roof of the bulla. Focal re-epithelialisation was present. Occasional necrotic keratinocytes were evident at the edge of the bulla. Mild epidermal spongiosis with lymphocyte exocytosis were evident. Immunofluorescence study showed intraepidermal intercellular staining of IgG and C3, and there was also dermo-epidermal junction staining of C3.

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescence study. IgG and C3 deposition at intercellular/basement membrane. Both specimens were from the patient.

Serological testing showed positive antibody titres against guinea pig and monkey oesophagus with intercellular patterns of titres 1:320. Other immune markers, including anti nuclear antibody, extractable nuclear antigens, rheumatoid factor and anti-cardiolipin, were negative.

In view of possible concomitant allergic reaction as supported by the abnormal eosinophil infiltration, chemotherapy was withheld and the patient was maintained on supportive care. She showed no significant improvement after 2 weeks of systemic steroid plus cessation of all inciting drug suspects. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), at a daily dose of 0.4 g/kg, was administered for 5 days. Clinical response was noted after one cycle as demonstrated by the regression of skin rash and mucositis; there was gradual resolution of symblepharon, minimal corneal haze, and complete healing of the epithelial defect. Her visual acuities returned to 20/20 bilaterally. Tear production remained poor. One week after IVIG, her Schirmer’s test reading was 2 mm and 3 mm over the right and left eyes, respectively.

Discussion

Anhalt et al defined PNP as “mucocutaneous eruption with characteristic histologic and immunological features in a patient malignancy”.1 The criteria used when he first described the condition in 1990 included: (1) polymorphic mucocutaneous eruption; (2) epithelial or epidermal acantholysis with interface dermatitis; (3) IgG and C3 deposition in intercellular areas and/or along the basement membrane; (4) indirect immunofluorescence on monkey oesophagus; and (5) the presence of desmoplakins and desmogleins. Autoantibodies found in patients with PNP targets multiple antigens, including various plakins (desmoplakin I, II, BPAG1, envoplakin, periplakin, and HD1/plectin)5–10 as well as desmogleins.11

Lymphoproliferative malignancies are most commonly associated with PNP.12 Mucocutaneous changes have been reported to develop before or during the course of illness, but none have recorded manifestation shortly after standard chemotherapy. Our patient suffered from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with no known allergic diseases. The presence of eosinophils in skin biopsy would support an allergic aetiology, but immunofluorescence study has proven otherwise. Moreover, significant anti-skin titre to monkey and guinea pig oesophagus (markers for pemphigus vulgaris) pointed more towards an immunological attack to primary skin antigens (intercellular desmosomes) than immune complex deposition seen in common drug eruptions. Thus, it is reasonable to suggest the presence of dual pathologies, but whether PNP was triggered by an allergic response cannot be proven; nor is it possible to speculate the course of skin changes should chemotherapeutic agents, which are sometimes used as immune modulating agents for autoimmune dermatoses, be continued.

Conjunctival involvement has been reported to occur in up to 70% of patients with PNP.13 Unlike pemphigus, cicatrisation is more likely to occur, and bilateral involvement was seen in all reported cases. Management objectives of PNP related eye disease are similar to other causes of CCC: to reverse the underlying cause, to prevent symblepharon formation and maintenance of the ocular surface maintenance, including adequate lubrication, prophylactic antibiotics and corneal protection. Systemic immune suppression may affect the course and prognosis of the underlying malignancy, especially when most cases are associated with lymphoproliferative diseases, thus caution should be rehearsed in avoiding vigorous dermatological treatment at the expense of cancer progression. Unfortunately, the prognosis of PNP associated with malignancy is generally poor and 90% of patients succumb within 2 years either from their neoplasms or the complications of treatment.14 Pulmonary involvement, a unique feature of PNP and one of the known causes of mortality,15 is characterised by mucosal shredding with subsequent bronchial obstruction. This had been suggested by the findings of an autopsy study,16 in which autoantibody deposition was found in bronchial epithelium and small airway plugging as a result of mucosal shredding from acantholysis and basal layer apoptosis. The subtle dyspnoea that developed in our patient may have represented such involvement.

Due to the poor prognosis and the few case reports available, knowledge on the natural course of ophthalmic manifestations of PNP is limited. Lam et al reported successful control of cutaneous eruption by prednisolone and azathioprine, but conjunctival cicatrisation has led to permanent symblepharon and forniceal shortening.17 Early detection and vigorous treatment might have prevented the occurrence of such complications in our patient.

Novel treatment modalities for PNP include oral prednisolone, immune suppressants such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, plasma exchange, IVIG and cyclophosphamide stem cell ablation.18 IVIG is among the most effective therapeutic options for treating this often intractable disease, either as an adjunct or sole treatment after failure of conventional immunosuppressants. It induces prompt reduction in circulating intercellular IgG,19 healing of existing mucocutaneous lesions and preventing new eruption20; nonetheless, therapeutic efficacy is related to circulating half life, and so numerous cycles may be necessary. Rituximab has been used with conflicting results.21,22 In retrospect, it is uncertain whether the regimen used since 2004 had any influence on the patient’s immune system in halting or reversing any possible evolving PNP.

Learning points

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a rare but serious cause of cicatrising conjunctivitis.

Diagnosis relies on clinical, histological and serological evidence.

The ophthalmologist should play an active role in monitoring disease activity and any response to treatment.

Vigorous measures are indicated to prevent potentially blinding complications as a result of ocular surface scarring.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Department of Pathology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong, for the preparation of the immunofluorescence images.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rashida S, Reza Danaa M. Cicatrizing and autoimmune diseases. Immune response and the eye. Chem Immunol Allergy 2007; 92: 195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anhalt GJ, Kim S, Stanley JR, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: an autoimmune mucocutaneous disease associated with neoplasia. N Engl J Med 1990; 323: 1729–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sklavounoua A, Laskaris G. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: a review. Oral Oncology 1998; 35: 437–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tilakaratnel WM, Dissanayake M. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: a case report and review of literature. Oral Diseases 2005; 11: 326–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anhalt GJ, Kim SC, Stanley JR, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: an autoimmune mucocutaneous disease associated with neoplasia. N Engl J Med 1990; 323: 1729–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SC, Kwon YD, Lee IJ, et al. cDNA cloning of the 210-kDa paraneoplastic pemphigus antigen reveals that envoplakin is a component of the antigen complex. J Invest Dermatol 1997; 109: 365–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiyokawa C, Ruhrberg C, Nie Z, et al. Envoplakin and periplakin are components of the paraneoplastic pemphigus antigen complex [letter]. J Invest Dermatol 1998; 111: 1236–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borradori L, Trueb RM, Jaunin F, et al. Autoantibodies from a patient with paraneoplastic pemphigus bind periplakin, a novel member of the plakin family [letter]. J Invest Dermatol 1998; 111: 338–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahoney MG, Aho S, Uitto J, et al. The members of the plakin family of proteins recognized by paraneoplastic pemphigus antibodies include periplakin. J Invest Dermatol 1998; 111: 308–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proby C, Fujii Y, Owaribe K, et al. Human autoantibodies against HD1/plectin in paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Invest Dermatol 1999; 112: 153–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amagai M, Nishikawa T, Nousari HC, et al. Antibodies against desmoglein 3 (pemphigus vulgaris antigen) are present in sera from patients with paraneoplastic pemphigus and cause acantholysis in vivo in neonatal mice. J Clin Invest 1998; 102: 775–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mimouni D, Anhalt GL, Lazarova Z, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus in children and adolescents. Brit J Dermatol 2002; 147: 725–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyers SJ, Varley GA, Meisler DM, et al. Conjunctival involvement in paraneoplastic pemphigus. Am J Ophthalmol 1992; 114: 621–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anhalt GJ. Paraneoplastic pemphigus. Advances in dermatology, Vol 12 Philadelphia: Mosby-Year Book, 1997: 77–97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nousari HC, Deterding R, Wojtczack H, et al. The mechanism of respiratory failure in paraneoplastic pemphigus. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1406–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fullerton SH, Woodley DT, Smoller BR, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus with autoantibody deposition in bronchial epithelium after autologous bone marrow transplantation. JAMA 1992; 267: 1500–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lam S, Stone MS, Goeken JA, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus, cicatricial conjunctivitis, and acanthosis nigricans with pachydermatoglyphy in a patient with bronchogenic squamous cell carcinoma. Ophthalmology 1992; 99: 108–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wade MA, Black MM. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: a brief update. Australasian J Dermatol 2005; 46: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Razzaque Ahmed A. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in the treatment of patients with pemphigus vulgaris unresponsive to conventional immunosuppressive treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 45: 679–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bystryn JC, Jiao D, Natow S. Treatment of pemphigus with intravenous immunoglobulin. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47: 358–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed AR, Avram MM, Duncan LM. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 23–2003. A 79-year-old woman with gastric lymphoma and erosive mucosal and cutaneous lesions. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 382–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoque SR, Black MM, Cliff S. Paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with CD20–positive follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with rituximab: a third case resistant to rituximab therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol 2007; 32: 172–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]