Abstract

The autonomy perspective of housework time predicts that wives’ housework time falls steadily as their earnings rise, because wives use additional financial resources to outsource or forego time in housework. We argue, however, that wives’ ability to reduce their housework varies by household task. That is, we expect that increases in wives’ earnings will allow them to forego or outsource some tasks, but not others. As a result, we hypothesize more rapid declines in wives’ housework time for low-earning wives as their earnings increase than for high-earning wives who have already stopped performing household tasks that are the easiest and cheapest to outsource or forego. Using fixed-effects models and data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, we find considerable support for our hypothesis. We further conclude that past evidence that wives who out-earn their husbands spend additional time in housework to compensate for their gender-deviant success in the labor market is due to the failure to account for the non-linear relationship between wives’ absolute earnings and their housework time.

Keywords: household labor, autonomy, gender display, PSID

1. Introduction

Among married couples, wives perform the majority of household labor even when both spouses work full time (Kamo 1988) and when wives earn as much as their husbands (Evertsson and Nermo 2007). This inequality in the division of household labor contributes to a gender gap in leisure time between fully-employed husbands and wives and may also contribute to the gender gap in wages, if wives’ more extensive housework responsibilities reduce the intensity of their labor market work (Hersch and Stratton 1997; Noonan 2001).

Brines (1994) proposed a provocative explanation for this phenomenon: that couples with “gender-deviant” relative earnings – that is, where the wife earns more than the husband – will compensate by adopting a gender-traditional division of household labor. Under this theory, wives’ housework hours will fall as they contribute a larger share of the couple's income, up to the point that they contribute half of the couple's income. However, as wives’ income share increases beyond this point, their housework hours will rise. Brines terms this pattern “gender display.” To avoid confusion with the broader use of this term (West and Zimmerman 1987), we refer to Brines’ model as “compensatory gender display”, emphasizing that this is a behavior enacted by breadwinner wives to compensate for their gender-deviant labor force outcomes.

The key empirical prediction of compensatory gender display is that breadwinner wives – wives who out-earn their husbands – will perform more housework than wives who have earnings parity with their husbands, and that, among breadwinner wives, housework hours will continue to rise as the wife's share of the couple's income continues to increase.

In contrast, the autonomy perspective hypothesizes that wives’ own earnings are a better predictor of their time in household labor. Although the causal mechanism has not been directly tested, one possibility is that wives’ increased earnings provide increased financial resources to purchase market substitutes for their housework time. The autonomy perspective predicts consistent declines in wives’ housework time as their earnings rise.

This paper challenges the predictions of compensatory gender display, but also argues that the autonomy perspective has insufficiently considered the constraints that lead even wives with high earnings to spend substantial time in housework. We hypothesize that limits in wives’ ability to outsource or forego time in household labor will lead to small additional reductions in housework time for wives at the high end of the earnings distribution. We further hypothesize that evidence previously interpreted as indicative of compensatory gender display behavior is instead an artifact of failing to account for the non-linear relationship between wives’ absolute earnings and their housework time. By appropriately controlling for this non-linear relationship, as well as using fixed-effects models to control for time-invariant attitudes and behaviors, we provide a rigorous evaluation of the theory of compensatory gender display. If no evidence is found for compensatory gender display, the supposition that wives are disadvantaged in terms of household labor time when they out-earn their husbands must be overturned.

Thus, the first goal of this paper is to test the validity of the assumption that the relationship between wives’ earnings and their time in housework is linear. If a non-linear relationship is found, the second goal is to assess whether the evidence for compensatory gender display is robust to models that allow a more flexible relationship between wives’ own earnings and their housework time. We begin by reviewing the existing literature on time in household labor, focusing on several resource- and gender-based theories. Next, we summarize our research questions and propose several reasons that the relationship between wives’ earnings and their time in housework may be non-linear. We then describe our data and analytic strategy. We follow with the presentation of our results and discussion of their robustness to alternative specifications. We conclude with a discussion of our findings and their implications.

2. Background

2.1 Resource-Based Theories of Household Labor

Wives’ financial resources are acknowledged to affect their household labor time, although the form of this relationship is contested. A core question is whether wives’ household labor time responds more strongly to their absolute earnings or their earnings relative to their husbands’ earnings. We label these the autonomy perspective and the relative resources perspective, respectively. In both perspectives, spouses’ financial resources are presumed to influence time in household labor net of time in the labor market. In other words, spouses with higher earnings are assumed to do less housework not simply because they spend, on average, more time in the labor market and therefore have less time available for household labor, but because they are advantaged by controlling greater financial resources. As a result, both perspectives imply that spouses’ resources should influence household labor time even after controlling for labor market hours.

The relative resources perspective (referred to sometimes as the bargaining perspective or dependency perspective), assumes that the spouse who controls more resources will have a more powerful bargaining position and, thus, can better achieve his or her desired outcome (Blood and Wolfe 1960). If housework is assumed to be an undesirable activity for both spouses, then, other things equal, the spouse with greater resources is expected to perform less housework than his or her partner (Bittman et al. 2003; Brines 1994; Evertsson and Nermo 2004). Under the relative resources perspective, wives’ housework hours should fall whenever their financial resources rise relative to those of their husbands, as greater resources give them greater power to bargain out of undesirable household chores.

Spouses’ relative financial resources may affect the balance of power within the relationship in two ways. First, spouses with higher wage-earning potential will have greater ability to support themselves in the event of a divorce. The spouse who is less dependent on the marriage for well-being will have a better bargaining position (Lundberg and Pollak 1996; McElroy and Horney 1981). Under this framework, spouses’ relative financial resources are best operationalized by the ratio of the spouses’ potential wages in the event of divorce (Pollak 2005).

Alternatively, spouses’ current financial contributions to the marriage may influence spouses’ bargaining positions, as they influence what is perceived as a fair exchange between spouses. Thus, if both spouses spend the same amount of time in the labor market, but one spouse earns more, it may seem “fair” or “appropriate” to both spouses that the breadwinner spouse performs less household labor. As a result, spouses’ relative financial resources can be measured by the share of the spouses’ current earnings that are provided by the wife (or the husband). Our work follows this second operationalization, as relative earnings have been the dominant operationalization of spouses’ relative financial resources in the empirical sociological literature on housework (see, Baxter, Hewitt, and Haynes 2008; Bianchi et al. 2000; Bittman et al. 2003; Brines 1994; Evertsson and Nermo 2004, 2007; Greenstein 2000; Gupta 2006, 2007; Presser 1994).

Empirical evidence has tended to support the predictions of the relative resources perspective, finding that wives’ time spent on housework is negatively associated with their earnings relative to their husbands’ (Baxter et al. 2008; Bianchi et al. 2000; Bittman et al. 2003; Presser 1994).

In contrast, the autonomy perspective emphasizes the role of the absolute level of wives’ earnings in determining their household labor time. The causal mechanism for this relationship has not been directly tested, but the outsourcing of household labor has been suggested as a likely cause (Gupta 2006, 2007). Under this perspective, it is economically rational for wives to reduce their time in housework as their earnings rise, as their greater financial resources allow them to purchase market substitutes for their household labor. This perspective is supported by findings that wives’ time in housework falls more rapidly with increases in their own earnings than with increases in those of their husbands (Gupta 2006, 2007; Gupta and Ash 2008). It is also consistent with evidence that spending on market substitutes for women's household labor, such as housekeeping services and meals away from home, rises more quickly with wives’ earnings than with husbands’ (Cohen 1998; Oropesa 1993; Phipps and Burton 1998). Even if spouses pool their incomes, this suggests that wives exercise greater control over the use of their own earnings than their husbands’.

More broadly, the autonomy perspective may be conceived of as encompassing any causal mechanism linking wives’ absolute earnings to lower time in household labor. Gupta (2006, 2007) proposes, for example, that high-earning wives may simply feel a reduced obligation to perform housework, even if they do not purchase a market substitute for their own household labor. It is also possible that high-earning wives are able to convince their husbands to take over more of the household labor, although Gupta (2006, 2007) does not find evidence for this hypothesis. The autonomy perspective has generally been specified empirically as a linear relationship between wives’ earnings and their time in housework (Gupta 2006, 2007).

2.2 Gender-Based Theories of Household Labor

Neither the relative resources perspective nor the autonomy perspective can explain why women with full-time jobs who earn as much or more than their husbands continue to perform the majority of household labor. Rather, it is clear that norms about gender reduce wives’ abilities to use their financial resources to reduce their hours of housework. Broader social norms may lead both spouses to systematically discount women's earnings (Agarwal 1997; Blumberg and Coleman 1989), giving wives less bargaining power than their financial resources would predict. From the standpoint of wives’ own perceptions, the resulting division of labor may seem fair, though it is not consistent with a gender-neutral model of bargaining (Hochschild 1989; Lennon and Rosenfield 1994).

Furthermore, because housework has a performative quality to it, embodying ideals of feminine and masculine behavior (West and Zimmerman 1987), a gendered division of market and domestic labor may produce the social and psychological rewards of conforming to traditional gender roles (Berk 1985). Conversely, women who deviate from these gendered cultural norms and reduce their housework substantially may experience social stigma and guilt (Atkinson and Boles 1984; DeVault 1991; Tichenor 2005). These socially-imposed costs may lead spouses to a division of labor that deviates from what would be expected from a gender-neutral logic based only on spouses’ relative incomes.

Thus, while spouses may negotiate the division of household labor based in part on what they perceive as a fair exchange, gendered norms of behavior and the discounting of wives’ financial contributions will yield greater responsibility for housework for wives than husbands, even when their earnings are similar.

2.3 Compensatory Gender Display

Compensatory gender display provides an alternative to the assumptions and predictions of a gender-neutral relative resources perspective, but articulates a narrower hypothesis than the gender-socialization or gender-performance perspectives previously discussed. The compensatory gender display framework posits that partners use housework to affirm traditional gender roles in the face of gender-atypical economic circumstances.

The compensatory gender display hypothesis was operationalized by Brines (1994) and other researchers (Bittman et al. 2003; Evertsson and Nermo 2004; Greenstein 2000; Gupta 2007) as a quadratic relationship between the share of the couple's household income that is provided by the wife or the husband and the housework hours of either spouse.1 Wives’ housework hours are expected to follow a U-shaped pattern, with wives’ housework time falling up to the point that they contribute about half of family income, and then rising as they out-earn their husbands by progressively larger amounts. Concomitantly, husbands’ housework hours are expected to increase as wives’ earnings rise relative to theirs but fall once their wives contribute more than about half of family income. These predictions contrast with those of the relative resources perspective, which suggest that wives’ housework hours should decline (and husbands’ rise) with increases in wives’ relative earnings, even among couples in which the wife earns more than the husband.

The core implication of the compensatory gender display framework is not its particular functional form2, but its claim that women who out-earn their husbands, instead of using their own financial resources to achieve greater gender equity in the division of household labor, are penalized at home for their success at work, doing more housework than they would have if they had not out-earned their husbands.

Empirical tests of compensatory gender display have generally supported its tenets, with two important challenges. Brines (1994) originally found evidence of compensatory gender display for men using a cross-sectional sample from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID). Subsequent work using data from the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH) (Bittman et al. 2003; Greenstein 2000), Australian time-use data (Bittman et al. 2003), and the PSID (Evertsson and Nermo 2004) found evidence of compensatory gender display for at least one gender. Among samples of American couples, support for compensatory gender display has been found using both the NSFH and the PSID (Bittman et al. 2003; Brines 1994; Evertsson and Nermo 2004; Greenstein 2000), although individual studies may find evidence consistent with compensatory gender display on the part of only one gender.

Gupta (1999) criticized Brines’ findings by showing that they were sensitive to the inclusion of the 3% of men who were most highly dependent on their wives. In later work using the NSFH, he showed that the observed quadratic relationship between relative resources and housework time found by Brines and others is an artifact of including as a control variable only the household's total income, rather than separate controls for husbands’ earnings and wives’ earnings, to reflect the stronger relationship between wives’ own earnings and their household labor time (Gupta 2007). Gupta challenges both compensatory gender display and the relative resources hypothesis and suggests that autonomy is the most appropriate framework through which to view the relationship between wives’ earnings and household labor time.

3. The Present Study

Gender-based challenges to resource theory have challenged the economic logic of bargaining and specialization and have attempted to explain why couples in which the wife earns the most divide housework in a way that is not economically rational. Little attention has been given to the question of why high-earning wives continue to do housework themselves rather than purchasing market substitutes for their own time or lowering the total amount of domestic production. While Gupta's (2007) finding demonstrates the importance of wives’ earnings in determining their household labor time, it does not consider ways in which constraints in wives’ desire or ability to forego and outsource household labor may moderate the degree to which wives’ behavior follows the predictions of autonomy. Although Gupta (2006) and Gupta and Ash (2008) find some evidence that the earnings-housework relationship is flatter at the high end of the earnings distribution, the small sample size of the NSFH makes it difficult to formally test the assumption of linearity, and the implications of this empirical result are not discussed in detail.

There is good reason to believe that the association between wives’ earnings and their housework time may not be linear. We propose that wives face heterogeneity in the costs associated with foregoing or outsourcing specific household tasks. Even among households with significant financial resources, constraints in households’ ability or desire to outsource or forego household labor may arise for several reasons. For example, Baxter, Hewitt, and Western (2009) show that attitudes about whether it is appropriate, affordable, and efficient to hire a domestic worker are related to the likelihood that a household pays for regular help with housework, even after controlling for differences in households’ financial resources. Transaction costs associated with outsourcing, particularly the costs of monitoring service providers, may also reduce the ease with which households can outsource household production (de Ruijter, van der Lippe, and Raub 2003). Furthermore, even among high-earning wives, doing housework is tied to a desire to be “good wives” (Atkinson and Boles 1984; Tichenor 2005). The husbands of high-earning wives also express a reluctance to let their wives’ career success interfere with her household production, suggesting that they may pressure their wives to do some household labor (Atkinson and Boles 1984; Hochschild 1989). Thus, the social construction of gender may constrain the ability of high-earning wives to forego housework time

If households’ attitudes toward the outsourcing of domestic labor can be captured with a single, time-invariant measure, then these attitudes cannot explain changes in wives’ housework hours that are associated with changes in their earnings. Similarly, if trust problems in outsourcing, a lack of availability of domestic workers, or gendered norms of behavior simply depress outsourcing by a constant amount, they cannot explain the relationship between wives’ earnings and their housework time.

The heterogeneity in the ease and desirability of outsourcing or foregoing different household tasks, however, provides a mechanism by which the non-linear association between wives’ earnings and their time in housework may arise. De Ruijter, van der Lippe, and Raub (2003) suggest that outsourcing will be inhibited when the costs of monitoring service providers are high, when outsourcing involves a loss of privacy for the household, and when it is more difficult to find providers who are deemed to provide an adequate quality of service or good. Compared to the outsourcing of meal preparation, hiring domestic workers may be less appealing to households because it is difficult to monitor the effort and quality of the service, the worker must be admitted into the home, often unsupervised, and domestic workers may be in relatively short supply in some areas. Likewise, households may view some household tasks as appropriate and efficient to outsource or forego, but not others. For example, it may be difficult to hire a domestic worker to handle unexpected and time-sensitive tasks, such as the cleaning up of spills. Without outsourcing household labor, it may be possible to forego some time cleaning by increasing the period of time between dustings, but less possible to forego the frequency with which meals are prepared. Wives are also less likely to forego or outsource tasks that have symbolic meaning or are associated with appropriate behavior for wives or mothers. For example, a wife may be willing to hire a domestic worker to dust the home, but not to prepare birthday meals for family members. What all of the proposed mechanisms have in common is that they recognize sources of heterogeneous constraint in wives’ ability to use their earnings to reduce their time in household labor.

Wives with low earnings may spend considerable time in housework because they lack financial resources to outsource this labor, and they may feel less free than high-earning wives to forego it, as they do not provide substantial financial resources to the household. Thus, when wives with low earnings experience an increase in earnings, this should translate into relatively large reductions in household labor time, as they outsource or forego household tasks for which they view this change to be easy, affordable, and appropriate. As wives’ earnings rise, we expect that they will increasingly forego or outsource housework, first giving up tasks that are perceived as the least costly to outsource or forego, and then gradually giving up tasks that incur higher costs, either financial or non-financial, when they are not done.

As earnings continue to rise, wives are left with household tasks that are difficult to forego or outsource – either because of difficulties in procuring an adequate substitute or because substitution is not perceived as appropriate. In other words, wives with high earnings are left with tasks that are performed primarily for non-financial reasons: further increases in earnings will not make outsourcing or foregoing these tasks more feasible. As a result, we predict that earnings increases for high-earning wives will have a smaller effect on their housework time, as the majority of the housework that remains is done for non-financial reasons, and hence, less likely to be outsourced or foregone. Thus, the ability of high-earning wives to outsource or forego housework time is constrained, though they still do less housework than they would if they earned less.

Our analysis is not designed to determine the precise cause of the non-linear relationship between wives’ earnings and their housework time. Instead, having outlined several theoretical reasons why such a relationship might occur, we propose to test empirically whether a non-linear relationship exists and, if it does, to determine whether failure to account for this relationship has led to spurious evidence in favor of compensatory gender display.

We now consider how our theory challenges existing empirical evidence for compensatory gender display. By assuming that financial resources, of either the household or the individual, facilitate declines in wives’ housework time at a constant rate, existing models have not allowed for the possibility of a non-linear relationship between wives’ earnings and their housework time. Compensatory gender display theory has, to date, been tested by including both linear and quadratic terms for spouses’ relative earnings and examining the sign and significance of the quadratic term. If, however, the relationship between wives’ absolute earnings and their time in housework is non-linear, constraining the relationship between absolute earnings and housework to be linear may lead to a spurious non-linear relationship between the share of household income wives provide and their housework hours. This is because wives’ absolute earnings are positively correlated with their share of household income. We use a more flexible specification of wives’ absolute earnings – a linear spline – to measure the relationship between wives’ share of household income and their housework hours.

Compensatory gender display is hypothesized to have explanatory power even after accounting for other predictors of spouses’ housework time, including their demographic characteristics, labor market hours, and absolute earnings. Therefore, if this theory as it has been articulated by Brines and others is correct, the quadratic relationship between wives’ relative earnings and their housework time should not disappear when a more flexible specification of wives’ absolute earnings is introduced to the model.

In addition, previous evaluations of compensatory gender display have not utilized longitudinal data that can control for the fact that couples in which the wife out-earns the husband may differ from other couples in systematic ways that affect their housework time. For example, these wives may also have high levels of energy and motivation that lead them to invest heavily in both market work and housework, or it may be the case that wives who are efficient in the labor force are less efficient at home, leading to high earnings but also long hours in housework. Likewise, evaluations of the autonomy perspective have made use of cross-sectional data (Gupta 2006, 2007). However, it is possible that high-earning wives spend less time in household labor not because of their earnings, but simply because wives with high earnings have fixed, unobserved traits that are correlated with lower levels of domestic production, such as a greater distaste for housework. In this case, it could not be said that wives’ earnings give them autonomy to reduce their time in household labor, as the relationship is spurious. Our analysis, which uses panel data and fixed-effects models, can control for such unobserved attributes of wives, as long as they do not vary over time. To our knowledge, we are the first researchers to directly test whether changes in couples’ labor force outcomes are associated with changes in their housework hours in a way that supports either the autonomy perspective or compensatory gender display.

4. Data and Methods

We use measures of spouses’ time in housework from the 1976-2003 waves of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID)3, as these are the years for which we can match these measures to earnings records from the same year. The panel nature of the PSID makes it an ideal dataset for evaluating how changes in spouses’ housework hours are associated with changes in their labor force outcomes and also provides us with a much larger sample size than the NSFH.

Our sample includes members of the core sample (1976-2003) and immigrant sample (1997-2003).4 Because our analyses make use of weighted data, we exclude all couple-year observations that have zero weight in either the cross-sectional or the panel analyses. This allows us to maintain a consistent sample for each model, although individual couples enter and leave the sample in different years. Each individual couple may appear in the sample in one or more years, depending on the number of years in which the couple is observed by the PSID and satisfies the sample restrictions. We restrict our analysis to married or long-term cohabiting heterosexual couples in which neither partner is above the age of 60.5 Before restricting the sample further, we re-code the top 1% of time use and earnings values to the 99th percentile, in order to avoid unduly influential observations.

We restrict our sample to couples in which both spouses are employed full time, defined as an average of at least 35 hours per week during the year. We discuss this decision in more detail below. However, as long as we adjust for the time spent in the labor force by spouses, our main results concerning compensatory gender display also hold in a sample restricted to husbands employed full time and wives employed part time (at least 20, but fewer than 35 hours per week), a sample of couples in which the wife works full time and the husband has any labor force status (including unemployed), and a sample of all couples in which the wife earns at least as much as her husband or will do so in the following year.

Although our results do not depend on analyzing only couples with two full-time workers, we present the results from this sample because in more heterogeneous samples it is difficult to avoid confounding the effects of labor specialization and resources. Studies that include couples with varying work hours typically include controls for the weekly hours spent in market work by each spouse or for the employment status (part-time, full-time, not employed) of each spouse in an attempt to distinguish the effects of time and financial resources. However, because earnings are the product of wages and labor market hours, this strategy will only be effective if the hours-housework relationship is properly specified. For example, the relationship between wives’ labor market hours and time in housework may be non-linear, or may vary depending on the husband's labor market hours. In this case, a linear control for the spouses’ time in the labor market will not fully adjust for differences in labor market time. Studying couples in which spouses are relatively similar in their time availability allows us to evaluate how spouses’ housework hours change in response to changes in their earnings, holding constant their employment status. The effect of employment changes on spouses’ housework hours has been discussed elsewhere and has not yielded results consistent with the predictions of compensatory gender display (see, for example, Gershuny, Bittman, and Brice 2005; Ström 2002).

4.1 Housework Hours

Following most previous evaluations of compensatory gender display, the key dependent variable is the individual's weekly hours spent in housework. PSID respondents are asked: “About how much time do you spend on housework in an average week—I mean time spent cooking, cleaning, and doing other work around the house?” This question does not impose a specific definition of housework. Although we estimated analogous models for husbands’ and wives’ time in housework, we present only the results for wives’ housework time in the main section. We found no evidence for compensatory gender display in any of the models of husbands’ time in housework using our main analytic sample (see Appendix A).

4.2 Financial Resources

We measure spouses’ financial resources with two separate variables—one for husband's annual earnings and one for wife's annual earnings—to address evidence that wives’ absolute earnings are a stronger determinant of their housework hours than are their husbands’ earnings (Gupta 2006, 2007; Gupta and Ash 2008). Annual labor income, as constructed by the PSID, includes overtime and bonuses as well as regular pay. Annual earnings are standardized to 2008 dollars using the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The functional form of the wife's absolute earnings varies across models: first a single linear term is considered and then a linear spline with three knots. The knots are placed at $23,925, $33,671, and $47,939, corresponding to the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of the weighted earnings distribution for wives. The spline specification constrains the relationship between wives’ earnings and their housework time to be linear between any two knots of the spline, but allows for different slopes between different pairs of knots. This allows a flexible relationship between wives’ earnings and their housework time. Husbands’ earnings are constrained to have a linear relationship with the housework hours of both spouses, for simplicity. Alternative models that allowed a spline specification of husbands’ earnings did not substantially alter the results.

We measure spouses’ relative financial resources as the share of the couple's total annual earnings that is provided by the wife. This reflects the view that spouses’ current financial contributions affect the division of household labor. We discuss the results when spouses’ relative wages are included in the discussion of alternative model specifications. In the main models, we follow the standard specification of compensatory gender display, including both a linear and quadratic term for the wife's share of the couple's earnings (Bittman et al. 2003; Brines 1994; Evertsson and Nermo 2004; Greenstein 2000; Gupta 2007).

4.3 Control Variables

In both the cross-sectional and panel models, we include covariates to adjust for time-varying characteristics of couples that may be correlated with both the financial variables and the household labor hours of each spouse. The first set of controls adjusts for life-cycle effects. Binary variables for the presence of at least one, at least two, and at least three children in the household, as well as a linear control for the age of the youngest child, are included to control for the association between the presence of children and women's household labor time (Baxter et al. 2008; Bianchi et al. 2000; Sanchez and Thomson 1997). In the cross-sectional models, linear controls for the ages of both the husband and the wife are included, as is a linear control for the year of the survey, to account for differences in housework hours across both the life course and time periods. In the panel model, only the control for the survey year is retained, due to the inability to separately identify age and period effects in fixed-effects models.

While the main models require that each spouse averages at least 35 hours of paid work per week during the year, we further control for the mean weekly hours of each spouse, to adjust for residual differences in labor force hours. Previous analyses have often found a negative relationship between individuals’ market labor time and their housework time and a positive relationship between individuals’ market labor time and their spouses’ housework time (Bianchi et al. 2000; Bittman et al. 2003; Evertsson and Nermo 2004). Weekly labor force hours are constructed by dividing the annual market work hours of the individual by 52. The values are then centered around 40.

We include an indicator variable for whether the couple owns their home, because home ownership may induce a preference for higher levels of domestic production and may also increase the amount of housework to be done.

Because the PSID collects all information in a given survey year from a single respondent, we also include a dummy variable that indicates whether the wife or another household member was the respondent in that year to guard against the potential for proxy response bias in spouses’ reported housework hours (Achen and Stafford 2005; Berk 1985). Because each couple-year observation includes information from two different survey years (labor force outcomes for year t are reported in survey year t+1), we include separate indicator variables for the respondent's identity in the year in which the demographic and housework information was collected and for the year in which the labor force information was collected.6

Finally, our cross-sectional models include time-invariant characteristics of couples that have been found to be associated with spouses’ housework hours: whether each spouse has a bachelor's degree and whether the husband is African-American or not.7 More educated couples (Baxter et al. 2008; Presser 1994; Sanchez and Thomson 1997) and African-American couples (Pittman and Blanchard 1996; Sanchez and Thomson 1997) have been found to be more egalitarian in the division of household labor than their less educated or white counterparts. For couples that are missing information on the race of the husband or the education of either spouse in a given year, we use information from the closest preceding non-missing year to impute these values. If no such information is available, we use information from the closest subsequent year.

4.4 Missing Data

From the original sample of 21,674 couple-year observations in which both spouses are working full-time, 0.8% of the sample fails to report valid data on the wife's weekly housework time and is excluded.8 We drop 1,279 observations in which either spouse reports annual work hours and earnings that imply an hourly wage of less than $4 per hour (in 2008 dollars), as this is below the minimum wage in every year. In particular, of these observations, 527, or 41% of them, were likely unpaid workers in family businesses as they reported no earnings even though they reported working more than 35 hours per week. Models of wives’ housework time that included observations with wages greater than $0 but less than $4 per hour produced results similar to those presented in the main models. Our final sample thus includes 5,059 couples, who are observed approximately 4.0 times each on average, for a total of 20,213 couple-year observations.

For covariates with non-zero missing data – race, education, the identity of the respondent, and home ownership – less than 2% of the sample has missing data. For education, race, and respondent identity, we create three dummy variables set to one if the observation lacks valid data for the item. The missing data dummy variable associated with a covariate is included in any model that includes the covariate. Only one observation is missing valid data for the home ownership variable. We re-code this observation into the “neither rents nor owns” group.

4.5 Analytic Approach

Our multivariate analysis proceeds in two stages. In the first stage, we document the relationship between wives’ earnings and their time in housework, without including a measure of spouses’ relative earnings. We do this using three models. Our first model uses ordinary least squares (OLS) and a linear specification of both husbands’ and wives’ annual earnings. Our second model retains the linear specification of both spouses’ earnings, but makes use of the panel nature of the PSID and is estimated using fixed effects. By comparing the results from these two models, we can assess the extent to which controlling for time-invariant attributes of couples affects our results. In particular, we are able to determine how much of the negative relationship between wives’ earnings and their housework time can be attributed to unobserved differences between high-earning and low-earning wives, rather than to a causal relationship. Our third model retains the fixed-effects specification but specifies the relationship between wives’ earnings and their housework hours as a linear spline with three knots.

In the second stage, we replicate the first three models, adding measures of spouses’ relative incomes, to test whether the evidence for compensatory gender display is robust to the use of fixed effects and a more flexible specification of the relationship between wives’ earnings and their time in housework.

Our OLS models are estimated with standard errors clustered at the couple level to account for the correlation across observations from the same couple. Under the fixed-effects framework, we assume that individuals’ (i) housework hours (hswk) across time (t) can be modeled as a function of time-varying predictors (X), individual-level match-specific9 fixed effects (α), and time-varying individual-level variation (ε), as follows:

Under OLS models, a single error term, , is implied. The clustered standard errors adjust for the lack of independence of the error terms for a given individual, since they share a common αi.

However, the coefficients estimated by OLS models are only unbiased if it can be assumed that is uncorrelated with X. If individuals’ tastes for housework and preferences for the level of domestic production in the household differ systematically across couples in ways that are correlated with the observed predictors of individuals’ housework time, there will be a correlation between these unmeasured individual-specific traits and the predictors of housework time, resulting in biased estimates of the OLS coefficients. For example, Oropesa (1993) finds that wives employed full time are less uncomfortable with an unclean house and like to cook less than other wives. Because the PSID does not measure attitudes toward domestic production, these attitudes and preferences are unobserved traits that may be correlated with spouses’ labor force hours and earnings. Fixed-effects models eliminate bias in the estimates of the coefficients that is due to a correlation between the predictors and time-invariant individual-specific effects, αi.

To summarize, we estimate one cross-sectional and two panel models, which differ by whether the relationship between wives’ absolute earnings and their housework hours is constrained to be linear or is allowed to vary across the earnings distribution as a linear spline. We then test for evidence of compensatory gender display in each model, investigating the stability of the evidence when either panel models or more flexible functional forms are introduced.

Both descriptive statistics and regression results are presented making use of the PSID household weights, which are re-scaled to average one in the full sample of each year, to make the weights from different years comparable. For panel models, the weight must be constant for each couple, so we use the household weight from the first year the couple is observed10.

5. Results

In Table 1, descriptive statistics for our primary analytic sample are presented for three periods: 1976-1984, 1985-1993, and 1994-2003. The average couple in our sample is observed in their late 30s or early 40s and 8-9% of the couples include an African-American man. The fraction of husbands and wives with college degrees rises from 22% and 13%, respectively, in the early period to 31% and 29% in the late period. Husbands’ median earnings are flat, falling between $49,500 and $51,500. Wives’ earnings show growth, as expected from the greater labor force experience and education of women in the later period, increasing from $30,810 in the early period to $37,032 in the latest period. This growth is reflected in a modest rise in the median share of couples’ earnings provided by wives, from 0.39 in the earliest period to 0.42 in the latest period. However, the fraction of wives earning more than their husbands rises substantially, from 15% to 26%, and the fraction of wives earning at least 50% more than their husbands rises from 4% to 9%. Hours spent in the paid labor market each week remain roughly constant for both husbands and wives. Husbands’ median weekly hours increase slightly from 41.9 hours in the early period to 43.5 hours in the late period, and wives’ median weekly hours rise from 38.5 to 39.2.

Husbands’ average housework hours are stable around 7 hours per week while wives’ average housework hours fall substantially, from 19.5 hours per week in the early period to 14.5 hours per week in the late period. The trends in wives’ average time in housework observed in this sample follow trends documented elsewhere, although we find little change in husbands’ housework hours over the period, while others have found a rise in men's housework time (Bianchi et al. 2000; Gershuny and Robinson 1988). We do, however, find a decline in the fraction of husbands who report doing no housework at all, from 15% in the early period to 8% in the late period.

5.1 Results for Linear Absolute Earnings

The earnings variables are the key independent variables of interest, so we discuss the results for these variables first. The first two columns in Table 2 report results from OLS and fixed-effects models that include a single linear term for the relationship between wives’ earnings and their time in housework. Wives’ earnings are significantly negatively related to their time in housework in both models, but the magnitude of the coefficient drops by 44% in the panel model. This suggests that a substantial portion of the observed negative association between wives’ earnings and housework time in cross-sectional models is due to unobserved differences between high-earning and low-earning wives, such as differences in tastes for housework, rather than to a causal relationship between earnings and housework time. In the cross-sectional model, each $10,000 increase in a wife's earnings is associated with a predicted decrease in her weekly housework time of 0.82 hours (49 minutes), while in the panel model the predicted reduction is only 0.46 hours (28 minutes).

Table 2.

Results from Models of Wives’ Housework Hours

| Linear Earnings | Spline Earnings | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Section | Panel | Panel | |

| Annual Earnings | |||

| His Annual Earningsa | -0.01 (0.04) | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.05) |

| Her Annual Earningsa | -0.82 (0.08)*** | -0.46 (0.09)*** | N/A |

| First Quartile | N/A | N/A | -1.85 (0.44)*** |

| Second Quartile | N/A | N/A | -1.02 (0.38)** |

| Third Quartile | N/A | N/A | -0.21 (0.25) |

| Fourth Quartile | N/A | N/A | -0.25 (0.11)* |

| Children | |||

| Age of youngest child | -0.10 (0.03)** | -0.17 (0.03)*** | -0.16 (0.03)*** |

| >=1 child | 3.46 (0.38)*** | 3.65 (0.37)*** | 3.59 (0.37)*** |

| >=2 children | 1.39 (0.30)*** | 0.71 (0.27)** | 0.69 (0.27)* |

| >=3 children | 2.03 (0.46)*** | 1.20 (0.49)* | 1.15 (0.48)* |

| Labor Force Hours | |||

| Husband's LF Hours | 0.04 (0.02)* | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) |

| Wife's LF Hours | -0.03 (0.03) | -0.03 (0.02) | -0.03 (0.02) |

| Year | -0.24 (0.02)*** | -0.13 (0.02)*** | -0.13 (0.02)*** |

| R2 / R2 overall | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Rho (fraction of variance due to individual-specific fixed effects) | N/A | 0.61 | 0.60 |

Notes: Results shown are regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. The sample includes 20,213 observations from 5,059 couples. In the cross-sectional models, standard errors are clustered at the couple level. All significance tests are two-tailed. All models also control for whether the couple owns their home, rents, or neither owns nor rents, and whether the wife or another member of her household was the respondent in each wave. The cross-sectional model also controls for the ages of each spouse, whether each spouse has a bachelor's degree, and whether the husband is African-American. The knots of the spline are placed at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of the weighted earnings distribution for wives: $23,925, $33,671, and $47,939.

Earnings are measured in $10,000s

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<0.001.

As expected from the autonomy perspective, wives’ own earnings are stronger predictors of their housework hours than are their husbands’ earnings. We are able to reject the null hypothesis that the coefficients on husbands’ and wives’ earnings are the same in both the cross-sectional (F (1, 5058) = 62.45, p-value<0.001) and panel (F (1, 5058) = 29.99, p-value<0.001) models. Thus, with the standard linear specification, there is support for the autonomy perspective. While the magnitude of the relationship between wives’ earnings and their housework time is reduced in the fixed-effects model, it is not eliminated, and wives’ earnings remain more important than husbands’ in determining wives’ housework time.

5.2 Results for Spline Models

The third column in Table 2 reports results from the fixed-effects model that specifies the relationship between wives’ earnings and housework time as a linear spline. The relationship between wives’ earnings and housework is strongly non-linear and the assumption of linearity is rejected (F (3, 5058) = 7.41, p-value<0.001). In the first piece of the spline, for wives in the lowest quartile of the earnings distribution, weekly housework time falls 1.9 hours with a $10,000 annual earnings increase. In the second quartile, a $10,000 increase is associated with a decline of 1.0 hour per week. Past the median, at about $34,000, the rate of the decline in wives’ housework hours is substantially reduced and never exceeds 0.25 hours for every $10,000 increase in earnings. The same earnings increase translates into housework reductions that are four times larger for a wife in the second quartile than for a wife above the median and nearly eight times larger for a wife in the first quartile than for a wife above the median.

If all wives reduced their housework hours at the rate implied by the lowest-earning wives, a change from the 10th percentile to the 90th percentile of the earnings distribution would decrease weekly housework hours by 8.8 hours. Holding the other covariates constant at their mean, and using the results of parallel models of husbands’ housework time, this would have the effect of closing the gap in housework time between spouses by 75%, to 2.8 hours per week. Given the non-linearity, however, a change from the 10th to the 90th percentile of the earnings distribution only reduces wives’ housework time by 2.9 hours and closes the housework time gap between spouses by only 31%, leaving a residual gap between spouses of 7.8 hours per week, even for wives at the 90th percentile of the earnings distribution. Thus, the ability of high-earning wives to achieve parity with their husbands in household labor is limited.

These results indicate a strong violation of the assumption of linearity that has traditionally been imposed in previous studies. At low levels of earnings, changes in wives’ absolute earnings are associated with substantial changes in their housework hours. Past the median, however, the decline in housework hours associated with increases in earnings is much flatter.

Given the results from Table 2, compensatory gender display does not appear to be the only way to explain the high housework hours of high-earning wives. Instead, our results indicate that high-earning wives do not do more housework than other wives, and they do not do high levels of housework because of their high earnings. Rather, they spend considerable time in housework in spite of their financial resources: their earnings buy significantly less relief than a linear relationship between earnings and housework would predict.

5.3 Non-linearity and its Implications for Compensatory Gender Display

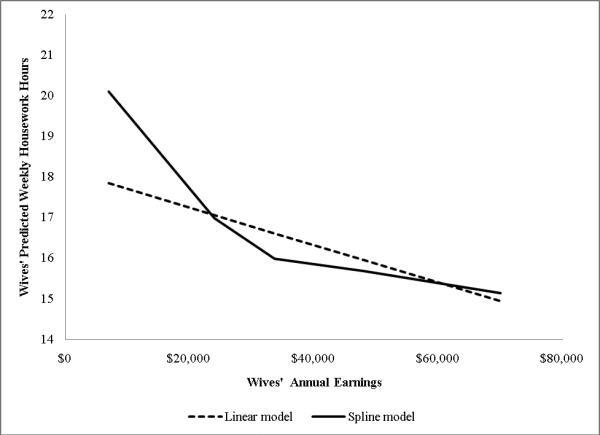

How might failing to account for the non-linearity shown in Table 2 lead to spurious evidence in favor of compensatory gender display? Imposing a linear relationship between wives’ earnings and their housework time will over-predict housework hours for wives at some points of the earnings distribution and under-predict them at other points. The differences between the predictions of the linear and spline specifications of wives’ earnings are illustrated in Figure 1. The dotted line shows the predicted weekly housework hours of wives at various points in the earnings distribution, using the estimates of the constant linear specification panel model. The solid line shows predicted weekly housework hours based on the spline panel model. The linear model under-predicts the housework hours of wives with the lowest earnings by 2.3 hours per week compared to the predictions of the spline model and over-predicts the housework hours of wives at the median by 0.6 hours. Thus, traditional linear models of wives’ time in household labor under-estimate the household labor of wives with the fewest financial resources and over-estimate that of middle-income wives.

Figure 1.

Wives’ Predicted Weekly Housework Hours, by Earnings.

Additional analyses indicate that wives’ absolute earnings are positively correlated with the share of family income that they provide (results not shown, available from the authors upon request). The bivariate correlation is 0.46, and non-parametric, smoothed (lowess) plots show a positive relationship between wives’ absolute earnings and the wife's share of family income across the entire range of wives’ earnings, although the relationship flattens out at higher earnings levels.11 Thus, in models that constrain the relationship between wives’ earnings and their time in housework to be linear, but allow the relationship between relative earnings and housework to be quadratic, the quadratic term of relative earnings picks up a non-linearity in the relationship between absolute earnings and time in housework. Because the linear model under-predicts the weekly hours for low-earnings wives and over-predicts them for median earners, the quadratic term for relative earnings will correct these prediction errors as much as possible. A positive quadratic term for relative earnings, then, tends to increase predicted housework hours of low-earning wives, who tend to contribute the least to family income, while decreasing the predicted hours of wives near the middle of the earnings distribution, who tend contribute a moderate share to family income. This term is then frequently interpreted as providing evidence for compensatory gender display.

Given these results, findings from previous studies that are consistent with compensatory gender display may be an artifact of assuming a linear relationship between wives’ earnings and their housework time. To test this hypothesis, we repeat the models shown in Table 2 but add the traditional linear and quadratic terms for the wife's share of family income. If ignoring the nonlinear relationship between wives’ earnings and their housework hours is the cause of evidence consistent with compensatory gender display, we would expect to see results consistent with compensatory gender display in the OLS and fixed-effects models that constrain the earnings-housework relationship to be linear, but not in the model that allows for a more flexible earnings-housework relationship. We discuss only the results for the measures of spouses’ relative incomes, as the coefficients on the other variables are largely unchanged from the models that excluded the relative incomes measures.

5.4 Results for Relative Earnings

The first two columns of Table 3 present the results from the OLS and fixed-effects models of wives’ housework hours with only constant linear terms for spouses’ absolute earnings. In these models, the coefficients on the linear and quadratic terms for relative earnings are consistent with compensatory gender display: in both the panel and the cross-sectional model the linear term is negative and significant, and the quadratic term is positive and significant. In both models it is possible to reject the joint null hypothesis that both coefficients are zero (F (2, 5058) =9.45, p-value<0.001 in the cross-section, F (2, 5058) =5.60, p-value=0.004 in the panel). In both models, wives’ minimum housework hours are predicted to occur when the wife provides more than half, but less than 100% of the couple's income; in other words, wives who out-earn their husbands the most do more housework than wives who out-earn their husbands by less. Thus, both models support compensatory gender display.

Table 3.

Results from Models of Wives’ Housework Hours, Including Relative Earnings

| Linear Earnings | Spline Earnings | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Section | Panel | Panel | |

| Relative Earnings | |||

| Wife's Share of Earnings | -18.42 (5.26)*** | -16.39 (5.12)** | -2.49 (6.58) |

| (Share)2 | 10.97 (4.84)* | 12.41 (4.76)** | 2.41 (5.50) |

| Annual Earnings | |||

| His Annual Earningsa | -0.29 (0.08)*** | -0.12 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.09) |

| Her Annual Earningsa | -0.34 (0.13)** | -0.17 (0.12) | N/A |

| First Quartile | N/A | N/A | -1.74 (0.60)** |

| Second Quartile | N/A | N/A | -0.98 (0.42)* |

| Third Quartile | N/A | N/A | -0.19 (0.30) |

| Fourth Quartile | N/A | N/A | -0.24 (0.13) |

| Children | |||

| Age of youngest child | -0.10 (0.03)** | -0.16 (0.03)*** | -0.16 (0.03)*** |

| >=1 child | 3.47 (0.38)*** | 3.62 (0.37)*** | 3.59 (0.37)*** |

| >=2 children | 1.33 (0.30)*** | 0.67 (0.27)* | 0.69 (0.27)* |

| >=3 children | 1.96 (0.46)*** | 1.17 (0.49)* | 1.15 (0.48)* |

| Labor Force Hours | |||

| Husband's LF Hours | 0.04 (0.02)* | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) |

| Wife's LF Hours | -0.03 (0.03) | -0.03 (0.02) | -0.03 (0.02) |

| Year | -0.23 (0.02)*** | -0.13 (0.02)*** | -0.13 (0.02)*** |

| R2 / R2 overall | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Rho (fraction of variance due to individual-specific fixed effects) | N/A | 0.60 | 0.60 |

Notes: Results shown are regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. The sample includes 20,213 observations from 5,059 couples. In the cross-sectional models, standard errors are clustered at the couple level. All significance tests are two-tailed. All models also control for whether the couple owns their home, rents, or neither owns nor rents, and whether the wife or another member of her household was the respondent in each wave. The cross-sectional model also controls for the ages of each spouse, whether each spouse has a bachelor's degree, and whether the husband is African-American. The knots of the spline are placed at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of the weighted earnings distribution for wives: $23,925, $33,671, and $47,939.

Earnings are measured in $10,000s

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<0.001.

The cross-sectional result contrasts with Gupta's (2007) finding that including separate (linear) terms for husbands’ and wives’ earnings eliminates the relationship between spouses’ relative incomes and their housework hours. In our PSID data, we do not find this strategy sufficient to reject predictions of compensatory gender display. To test whether this result is due to our exclusion of couples in which the husband works less than full time, who are included in Gupta's sample but not in our own main sample, we repeat the cross-sectional analysis with a sample that restricts only the wife's employment to at least 35 hours per week and wages to at least $4 per hour, but allows the husband to have any level of labor force commitment. In this sample, too, the results are consistent with compensatory gender display. Gupta's (2007) finding that, in the NSFH, controlling separately for husbands’ and wives’ earnings suffices to eliminate the evidence in favor of compensatory gender display, does not appear to be robust with the PSID.

Here, the way in which our work moves beyond the specification of Gupta (2007) becomes important: the non-linearity of the relationship between wives’ absolute earnings and housework hours entirely explains the non-linear relationship between wives’ relative earnings and their housework hours. In the final column of Table 3, after including a more flexible specification of wives’ earnings, the magnitudes of the coefficients on the relative resources terms shrink considerably, both the linear and the quadratic terms for the share of income provided by the wife are no longer significant, and it is no longer possible to reject the joint null hypothesis that the coefficients on both relative resources terms are zero (F (2, 5058) =0.10, p-value=0.90). This eliminates any evidence for compensatory gender display. However, the negative relationship between wives’ absolute earnings and their housework time remains significant (F (4, 5058) =3.49, p-value=0.008) and the assumption of linearity is still strongly rejected (F (3, 5058) =4.04, p-value=0.007). Thus, consistent with the autonomy perspective, we find no evidence for compensatory gender display and find that wives’ absolute earnings are always negatively associated with their housework hours. However, we also find, as in Table 2, that the housework reductions associated with increased earnings diminish considerably at higher levels of wives’ earnings.

In summary, across specifications our results show that housework hours decline as earnings increase throughout the distribution of wives’ earnings. However, at higher earnings levels, the reduction in housework when earnings increase is smaller than it is when earnings increase for wives below the median level of earnings. In contrast to compensatory gender display, high-earning wives do less housework than low-earnings wives, even when they earn more than 50% of their family's total earnings.

5.5 Results for Control Variables

Because the relationships between the control variables and wives’ housework hours are similar across the three models presented in Table 2, we discuss the results from all models together. In all models, a first child is associated with an average increase of around 3.5 hours per week of wives’ housework, while the additions of second and third children have significant, but smaller positive associations with housework time. In both the cross-sectional and panel models, wives’ housework hours decline modestly with increases in the age of the youngest child. Support for the time availability hypothesis is weak in this sample, as changes in neither husbands’ nor wives’ weekly labor market hours are significantly associated with changes in wives’ time in housework in the panel models.

5.6 Specification Checks

Our specification checks focus on the panel models with the flexible specification of wives’ earnings (Table 3, Column 3). We check both whether our results are robust to alternative model specifications and whether the results hold for subgroups based on race, education, age, marital status, and parental status, as well as for observations from different time periods. We discuss our alternative model specifications and the results in more detail in this section (full results available from the authors upon request).

One critique of the preceding results might be that they are the artifact of either an insufficiently flexible specification of the husband's earnings or relative earnings, or of the number and placements of the knots in the linear spline model. To address the first concern, we consider models that included the husband's earnings as well as the wife's as a linear spline, as well as models that specify both the wife's earnings and spouses’ relative earnings as linear splines, always choosing knots that roughly divide the sample into quartiles. To address the second concern, we consider models that included up to six knots in the spline for wives’ earnings. In these models there is no evidence consistent with compensatory gender display, and it is never possible to reject the joint null hypothesis of no relationship between the share of income provided by the wife and her housework hours.

Allowing additional knots in the earnings-housework relationship also allows us to explore more fully the shape of the non-linear relationship between wives’ earnings and their time in housework. As in the main models, the median of the earnings distribution appears to be a key point of change: in the model with five knots, we find that in each of the three pieces of the spline below the median wives’ housework hours fall at least one hour per week for every $10,000 increase in annual earnings, while in the three pieces above the median they fall no more than 0.4 hours for every $10,000 increase in annual earnings. Again, the spline results support our finding that housework reductions associated with increased earnings are much smaller for high-earning wives than low-earning wives. We also consider models with alternative specifications of the dependent variable, using either the share of the spouses’ total housework time that is done by the wife, or the difference between the spouses’ housework hours. Neither of these alternative specifications provides evidence consistent with compensatory gender display.

For our race, education, age, marital status, parental status, and period subgroup analyses, we consider six pairs of subgroups: pre-1990 and post-1989 observations; couples in which the husband is African-American and those in which he is not; couples in which the wife has a bachelor's degree and those in which she does not; couples in which the wife is more than 40 years of age and those in which she is not; couples who have children and those who do not; and couples who are married as opposed to those who are cohabiting (in years in which it is possible to make this distinction). We find evidence consistent with compensatory gender display for only one of the six subgroup pairs – women married to African-American men. These results may suggest a need for greater attention in future research to differences by race in the evidence for compensatory gender display, although the smaller sample size of African-Americans makes us cautious in interpreting these results. In particular, the result is not significant when the analysis is further restricted to wives married to African-American husbands who earn at least as much as their husbands, suggesting that the result may reflect a non-linear relationship between earnings share and housework hours for wives who are out-earned by their husbands, rather than that breadwinner wives spend more time in housework than those who have earnings parity with their husbands. Furthermore, one prediction of compensatory gender display is that wives’ housework hours should continue to rise as they out-earn their husbands by greater amounts. However, we find no evidence that African-American wives who substantially out-earn their husbands (by more than 50%) spend more time in housework than wives who out-earn their husbands by smaller amounts.

Note that the estimated coefficients in fixed-effects models are determined by the relationship of changes in couples’ characteristics across years to changes in their housework hours across years. If there is little variation in spouses’ earnings across years, these coefficients may be problematic, especially if couples are observed only a small number of times. To test this hypothesis, we repeat both our main models and all of our subsample analyses using OLS models that include the same spline in wives’ earnings, as well as the control variables used in the OLS models presented in the main analysis. In both the full sample and all other subgroups, the results are entirely consistent with the results from the fixed-effects models: there is still no evidence for compensatory gender display, except among the women married to African-American men, and we again find a strongly non-linear relationship between wives’ earnings and their time in housework. Therefore, our main conclusions are not dependent on our decision to use fixed-effects models.

To test the predictions of the relative resources perspective, we repeat the model from the third column of Table 3, but exclude the quadratic measure of spouses’ relative incomes. If the predictions of the relative resources perspective are correct, we would expect that the coefficient on the linear term would be negative and significant, but we find that it is positive and not significant in the panel model and negative and not significant in the cross-sectional model. As discussed earlier, bargaining power between spouses may also be thought of as determined by spouses’ relative earnings power, typically measured as the ratio of their wages. Replacing the relative incomes measures with relative wages produces no evidence of either relative resources or compensatory gender display once we control for the non-linear relationship between wives’ wages and their housework time. Therefore, we find no evidence for the relative resources perspective.

We consider the possibility that our results may be biased by the inclusion of proxy reports of wives’ housework time. While we have included controls for whether the wife reported her own housework hours, it is possible that the extent of proxy response bias varies with the earnings of the wife. To test this hypothesis, we repeat the models from Table 2, Column 3 and Table 3, Column 3, restricting the sample to couples in which the wife was the respondent for both her housework hours and the spouses’ earnings. There is no evidence in favor of compensatory gender display in this sample, and again wives’ housework hours fall most rapidly with earnings increases when they are in the first quartile of the earnings distribution and least rapidly when they are above the median. Furthermore, we repeat the model from Table 2, Column 3, which excludes the relative earnings terms, and allow the respondent's identity to interact with the coefficients on wives’ earnings. The estimated earnings coefficients do not differ significantly depending on whether the husband or the wife was the respondent, suggesting that proxy response bias is not responsible for the estimated coefficients in the main models.

Lastly, we performed several supplemental analyses using the measure of expenditures on food away from home (the only market substitute about which the PSID collects information). We find no evidence of a non-linear relationship between wives’ earnings and household expenditures on food away from home. Furthermore, models that control for expenditures on food away from home show the same non-linear pattern observed in the main models.

5.7 Limitations

The present study has a few limitations. In terms of measurement, we lack information on wives’ time spent in child care, which is an important component of wives’ non-market work. However, the exclusion of time in child care from analyses of housework time is standard (Coltrane 2000), including in previous assessments of compensatory gender display. This exclusion is in part because it is not possible to separate the leisure and labor components of child care (Blair and Lichter 1991), and evidence suggests that parents view time with children differently from either housework or leisure (Guryan, Hurst and Kearney forthcoming).

Analytically, while fixed-effects models account for unobserved time-invariant differences across couples, they cannot prevent bias introduced by a correlation between the individual-year error term and the covariates. For example, the PSID does not include annual measures of gender role attitudes, a variable that may be associated with both wives’ earnings and their time in housework. Any time-invariant component of this measure – an individual's average attitudes during the period she is observed – will be absorbed by the fixed effects and will not affect our results. However, year-to-year fluctuations in gender role attitudes may be correlated with changes in both housework hours and earnings, and the fixed effects do not account for this correlation.

Lastly, while we have established that a negative and non-linear relationship exists between wives’ earnings and their housework time, we acknowledge that it is not possible for us to determine the causal mechanism responsible for this relationship. Wives may decrease their time in housework as their earnings rise either because they are outsourcing domestic labor or because they are foregoing housework without purchasing a substitute for their own time. Similarly, it is not possible to determine whether the non-linear relationship between wives’ earnings and their time in housework is due to a general discomfort with outsourcing, a reluctance to outsource or forego household tasks with symbolic significance, missing markets for some forms of outsourcing, distrust of providers of substitutes for household labor, or some other reason. Thus, further research is needed to identify the causal mechanism responsible for these relationships.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Our results highlight both the importance of and limits of financial resources in shaping wives’ time in household labor. Consistent with the autonomy perspective, we find that wives’ housework time declines with earnings increases at every point in the earnings distribution. This implies that wives have achieved partial success in changing the terms of the heterosexual partnership, as they are able to reduce their domestic labor when their financial contributions to the marriage are high. In other words, wives have some discretion in the type of goods – financial or domestic – that they provide to a partnership. This is consistent with work indicating that conceptions of appropriate behavior for women now include paid labor as well as domestic production (Riggs 1997; Sayer 2005), and that husbands enjoy the financial rewards provided by their wives’ careers (Atkinson and Boles 1984). Clearly, individual financial resources matter.

However, we estimate a smaller effect of wives’ earnings on their housework time than is hypothesized by the simplest form of the autonomy perspective. First, we find that this relationship is reduced considerably in the panel models, indicating that it is explained in part by unobserved differences between wives with low and high earnings, rather than being exclusively due to increased out-sourcing or foregoing of domestic labor as wives’ earnings rise. Second, we find that low-earning wives decrease their housework hours more than others as their earnings increase, while increased earnings above the median of the wives’ earnings distribution lead to only small reductions in household labor time. If wives’ time in housework were the result of a straightforward market decision, we would not expect so little additional decline in housework as wives’ earnings rise past the median of the earnings distribution. While wives’ housework time falls as their earnings rise throughout the earnings distribution, the overall decline is modest.

Our data do not permit us to determine whether the constraints on wives’ housework reductions emerge due to wives’ desire to do housework in order to “do gender” (Berk 1984; West and Zimmerman 1997), or to express love for family members (Devault 1991), or because of limits in the outsourcing of household production that are not due to gender norms, such as the lack of availability of substitutes for certain types of household labor. What is certain, however, is that wives experience a limitation in housework reductions that does not apply to husbands. That is, there is something about the experience of being a wife, as opposed to a husband, that causes even high-earning wives to spend considerably more time in housework than their husbands, even when they outearn them. Thus, even causal mechanisms that are gender-neutral in theory have gender-asymmetric effects on spouses’ housework time, as it is wives, not husbands, who perform the majority of household labor that is not outsourced or foregone by couples. As a result, wives cannot fully compensate for their disadvantaged role as women by leveraging their advantaged financial position. In other words, women cannot easily buy their way to equality with men when it comes to household labor responsibilities.

In addition to calling for greater attention to limits in wives’ ability to outsource or forego domestic labor, our work questions the predictions of compensatory gender display. Once we have accounted for the non-linear relationship between wives’ absolute earnings and their housework time, we find no evidence of compensatory gender display. In contrast to the predictions of compensatory gender display, we find no evidence that wives are penalized at home for their success in the labor market: in terms of household labor, it is never worse to earn more. Thus, contrary to compensatory gender display, wives’ earnings are best seen as a resource for reducing household labor, not as a liability.

While rejecting the narrow hypothesis of compensatory gender display, our findings highlight the importance of the gendered division of household labor in shaping the behavior of women at all income levels. The continued high levels of housework by high-earning wives show that more than money is needed for wives to achieve parity with their husbands in household labor time. Furthermore, our results indicate not only the limits of financial resources in determining wives’ time in housework, but also heterogeneity in the ways in which gender and financial resources interact to shape women's lives: low-income wives are constrained to perform domestic labor by their lack of financial resources, while high-income wives are constrained in spite of them.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| 1976-1984 (N=4824) | 1985-1993 (N=8403) | 1994-2003 (N=6986) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Husband's Annual Earnings | $50,787 | $51,200 | $49,650 |

| Standard Deviation | ($28,364) | (34,295) | (38,368) |

| Median Wife's Annual Earnings | $30,810 | $33,245 | $37,032 |

| Standard Deviation | ($15,983) | (19,416) | (21,606) |

| Median Wife's Share of Earnings | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.42 |

| Standard Deviation | (0.11) | (0.13) | (0.13) |

| Proportion of Wives Out-earning their Husbands | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.26 |

| Proportion of Wives Earning at Least 50% more than their Husbands | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Mean Husband's Weekly Housework Hours | 6.95 | 7.37 | 7.03 |

| Standard Deviation | (6.61) | (6.31) | (5.89) |

| Mean Wife's Weekly Housework Hours | 19.53 | 16.14 | 14.46 |

| Standard Deviation | (10.32) | (9.27) | (8.65) |

| Proportion of Husbands with no Housework Hours | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Median Husband's Weekly Employment Hours | 41.92 | 43.19 | 43.48 |

| Standard Deviation | (9.40) | (9.33) | (8.49) |

| Median Wife's Weekly Employment Hours | 38.46 | 38.85 | 39.23 |

| Standard Deviation | (4.52) | (5.43) | (5.62) |

| Mean Husband's Age | 38.83 | 39.29 | 41.28 |

| Standard Deviation | (10.46) | (9.40) | (9.26) |

| Mean Wife's Age | 36.26 | 37.04 | 39.34 |

| Standard Deviation | (9.98) | (9.11) | (8.94) |

| Proportion of African-American Husbands | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Proportion of Husbands with College Degree | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.31 |

| Proportion of Wives with College Degree | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.29 |

| Proportion of Couples Owning their Home | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.83 |

| Proportion of Housework Reports Provided by Wife | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.48 |

Notes: Reported sample sizes reflect couple-year observations.

Acknowledgments