Abstract

A 27-year-old man presented with a 5 day history of abdominal pain and distension, with associated constipation and vomiting. He had presented 8 years earlier following a traumatic injury to the left side of the chest, and no diaphragmatic injury was reported at that time. On this admission, a computed tomography scan showed herniation of the splenic flexure of the colon into the left hemithorax. Subsequently, he had an emergency laparotomy for resection, with formation of a loop ileostomy. The various imaging techniques all have advantages and disadvantages when diagnosing a traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. It is the clinician’s role to maintain a high index of suspicion when a patient initially presents with trauma where a traumatic diaphragmatic hernia may be a possibility.

Background

Traumatic diaphragmatic injuries are becoming of increasing significance in the UK due to the high prevalence of knife crime. Visualisation of the diaphragm is difficult because of its thinness, its domed contour, and its continuity with soft tissues of the abdomen. Difficulty in diagnosing early diaphragmatic hernia on plain x-ray, coupled with the fact that the interval phase of herniation is often asymptomatic, often results in delayed presentation of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia.

Case presentation

A 27-year-old man presented to the accident and emergency department with a 5 day history of generalised, constant abdominal pain and distension, associated with constipation and vomiting. He described an additional sharp intermittent pain in the left upper quadrant, which was worse on inspiration. Eight years previously, the patient had sustained a left posterior chest wall penetrating injury during an assault and presented at another hospital.

Investigations

Chest x-ray showed a left lower zone shadow, raising the possibility of left lower zone pneumonia with a cavitating lesion (fig 1). However, the finding of massively dilated loops of both large and small bowel on plain abdominal x-ray, confirmed by a computed tomography (CT) scan, indicated large bowel obstruction (fig 1). The CT also suggested that this obstruction was probably due to herniation of the splenic flexure of the colon into the left hemithorax.

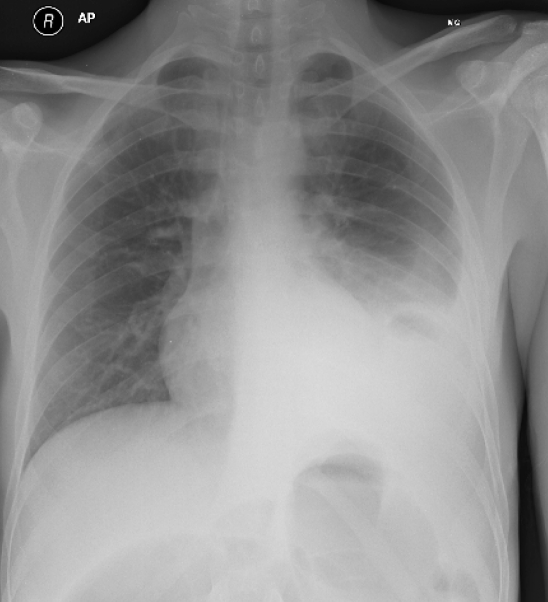

Figure 1.

Chest x-ray, posterioanterior view showing dense opacity at left base with air fluid level and pleural effusion.

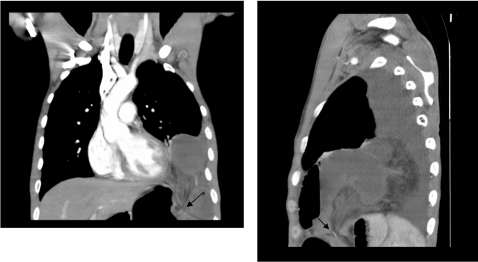

Figure 2.

Coronal and sagittal computed tomography scan images showing focal defect (arrows) in the anterior and lateral aspect of left hemidiaphragm, with intrathoracic herniation of colon and omentum resulting in large bowel obstruction.

Treatment

Emergency laparotomy was carried out, and the distal transverse colon and the splenic flexure were found to have herniated into the left hemithorax through a very small defect in the left hemidiaphragm causing strangulation. The entire omentum was also in the left hemithorax.

It appeared that the colon and the omentum had been in the chest for some time, as there were fibrous adhesions.

The strangulated colon was reduced and resected, the diaphragm was repaired, and a left chest tube was inserted. The omentum was ischaemic and also required resection. Colonic continuity was restored by colo-colic anastomosis and covered by a loop ileostomy.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperatively, the patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged after seven days.

Discussion

This patient had sustained his diaphragmatic injury 8 years previously, which was missed at initial presentation, most probably due to its asymptomatic nature. This is not the first case report, nor will it be the last, of delayed presentation of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. In fact, there is a case that reports the repair of a diaphragmatic hernia as late as 45 years following the initial trauma.1 Although it is well established that areas such as South Africa have a greater prevalence of thoraco-abdominal injuries, the Home Office latest figures show that almost one in five offences of attempted murder, grievous bodily harm or robbery in the UK involved knives or sharp instruments.2

Penetrating diaphragmatic injuries from bullets or knives can cause small holes, often <1 cm in diameter.3 The negative intrathoracic pressure that this generates is thought to cause gradual herniation of organs into the thorax. The “interval” phase of herniation, defined as occult diaphragmatic herniation,4 is often asymptomatic or manifests as vague dyspeptic symptoms or upper abdominal discomfort. Therefore, it is not uncommon for presentations of such cases to be delayed.

There may be benefit in following up this group of patients with penetrating thoraco-abdominal injuries, with regards to minimising the risk of developing a diaphragmatic hernia at a later stage. The longer the delay in diagnosis, the greater the morbidity and hospital stay, with mortality figures5 reaching up to 30% in cases with bowel strangulation associated with diaphragmatic hernia.6,7 For this reason, it is important to identify an appropriate imaging technique for this surveillance.

Visualisation of the diaphragm is difficult because of its thinness, its domed contour, and its continuity with the soft tissues of the abdomen.8 Furthermore, different techniques have their own limitations. Plain radiography is often the first investigation of choice, but it is recognised that this may be normal in the initial phases of herniation.9 Although some studies have reported10 that chest radiography is diagnostic of traumatic diaphragmatic injury in 68% of cases, many other studies report poorer rates of only 20–40%.11–14 These rates suggest that chest radiography alone may not be a good investigation for the early recognition of a diaphragmatic hernia following injury.

Barium studies may be used to diagnose thoracic herniation of the stomach, small intestine and colon.9 One study in patients with penetrating injuries reports the sensitivity of contrast radiographs as 72–78%. Furthermore, with the addition of ultrasonography the sensitivity is 82%.15

Although CT is a very useful and reliable tool for detecting diaphragmatic hernias, evaluation of the diaphragm integrity on dome and costal attachments may not be possible on standard axial CT images.9 Multislice helical CT with sagittal, coronal, and three dimensional reformatted images is more likely to be effective at detecting subtle changes that indicate diaphragmatic injury at follow-up. One study reports that the sensitivity of helical CT for detecting left sided diaphragmatic rupture is 78% and specificity is 100%.16

Alternatively, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, which is known to be sensitive for soft tissue, could be used. MR would not only identify the hernial orifice as a diaphragmatic discontinuity, but could also reveal other abdominal organ injuries.17 Although both CT and MRI would be likely to detect early signs of a traumatic diaphragmatic hernia, the poor cost effectiveness makes them inappropriate methods to routinely follow-up all patients who have had a chest or abdominal injury.

There is less evidence for the use of laparoscopy, in comparison to other imaging techniques, to diagnose suspected diaphragmatic hernia in high risk patients at the time of initial presentation. However, laparoscopy would also have the benefit of correcting the hernia at the time of diagnosis, avoiding laparotomy in up to 55% of patients.18

Learning points

It is the clinician’s role to maintain a high index of suspicion with these patients at initial presentation, and to arrange subsequent imaging to diagnose the development of a diaphragmatic hernia at an early stage.

Various imaging techniques have been evaluated for their usefulness in diagnosing traumatic diaphragmatic hernia when a patient presents with symptoms.

A technique with a high sensitivity to identify patients with early signs of a diaphragmatic hernia at follow-up is required. However, there is lack of evidence to support the use of any particular imaging technique for this purpose.

Further studies are required to identify the best technique, taking into consideration its cost effectiveness, as well as its sensitivity and specificity.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown GL, Richardson JD. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia: a continuing challenge. Ann Thorac Surg 1985; 39: 170–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Home Office. http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs08/hosb0708snr.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shackleton KL, Stewart ET, Taylor AJ. Traumatic diaphragmatic injuries: spectrum of radiographic findings. Radiographics 1998; 18: 49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter BN, Giuseffi J, Felson B. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. AJR 1951; 65: 56–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demetriades D, Kakoviannis S, Parekh D, et al. Penetrating injuries of the diaphragm. Br J Surg 1998; 75: 824–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Worthy SA, Kang EY, Hartman TE, et al. Diaphragmatic rupture: CT findings in 11 patients. Radiology 1995; 194: 885–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heiberg E, Wolverson MK, Hurd RN, et al. CT recognition of traumatic rupture of the diaphragm. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1980; 135: 369–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trver RD, Conces DJ, Jr, Cory DA, et al. Imaging the diaphragm and its disorders. J Thorac Imaging 1989; 4: 1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eren S, Ciris F. Diaphragmatic hernia: diagnostic approaches with review of the literature. EJR 2004; 54: 448–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelman R, Mirvis SE, Gens D. Diaphragmatic rupture due to blunt trauma:sensitivity of plain chest radiographs. AJR 1991; 156: 51–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez Morales G, Rodriguez A, Shatney CH. Acute rupture of the diaphragm in blunt trauma: analysis of sixty patients. J Trauma 1986; 26: 438–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thillois JM, Tremblay B, Cerceau E, et al. Traumatic rupture of the right diaphragm. Hernia 1998; 2: 119–21 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nursal TZ, Ugurlu M, Kologlu M, et al. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernias: a report of 26 cases. Hernia 2001; 5: 25–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadeghi N, Nicaise N, DeBacker D, et al. Right diaphragmatic rupture and hepatic hernia: an indirect sign on computed tomography. Eur Radiol 1999; 9: 972–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruf G, Mappes HJ, Kohlberger E, et al. Diagnosis and therapy of diaphragmatic rupture after blunt traumatic and abdominal trauma. Zentralbl Chir 1996; 121: 24–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Killeen KL, Mirvis SE, Shanmuganathan K. Helical CT of diaphragmatic rupture caused by blunt trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999; 173: 1611–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wataya H, Tsuruta N, Takayama K, et al. Delayed traumatic hernia diagnosed with magnetic resonance imaging. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi 1997; 35: 124–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zantut Luis F, Ivatury Rao R, Stephen Smith R, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy for penetrating abdominal trauma: a multicenter experience. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care 1997; 42: 825–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]