Abstract

Diffuse cavernous haemangioma of the rectum (DCHR) is an uncommon vascular pathology usually diagnosed in younger patients (5–25 years old) with painless, recurrent rectal bleeding. Here, an unusual case of an older patient with sigmoid adenocarcinoma and concomitant diffuse DCHR from the rectum to the distal edge of the anal canal is reported.

The purpose of this article is to report this unusual case and to discuss pitfalls in diagnosis, preoperative assessment and treatment of DCHR.

BACKGROUND

Diffuse cavernous haemangioma of the rectum (DCHR) is a rare benign vascular lesion with extremely uncertain etiopathogenesis. About 150 cases have been reported in the literature.1,2 Only a few cases report extension of the disease from the rectum to the anus.3 Patient ages usually range from 5 to 25 years and the principal presenting symptom is painless, massive rectal bleeding. Cavernous haemangioma of the rectum is often misdiagnosed due to a lack of knowledge of the clinical, endoscopic and radiological features. We present a case of a 75-year-old man with a recent diagnosis of sigmoid adenocarcinoma and concomitant DCHR extending to the anus.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 75-year-old man presented to our outpatients clinic with recurrent rectal bleeding. His medical history included acute myocardial infarction at age 65, benign prostate hypertrophy and hypertension. His surgical history revealed three previous haemorrhoidectomies at ages 16, 50 and 60, which did not prevent further rectal bleeding. His medications included only a β blocker and α lytic drug. Social history was non-contributory. Familiar history was negative for colorectal cancer.

Physical examination showed a healthy 75-year-old man with no evidence of mucocutaneous or vascular lesions and no signs or symptoms of anaemia. Rectal examination showed multiple anal scars from previous surgery. No rectal mass was palpated but red blood in the ampulla was detected. The resting and squeezing tone of the anal sphincter was within normal limits.

INVESTIGATIONS

Pancolonoscopy revealed a 2.5 cm sessile mass with superficial erosion in the sigmoid colon, 25 cm from the anal verge. The rectal mucosa appeared diffusely irregular, with submucosal vascular proliferation features and moderate narrowing of the lumen. Multiple biopsies were taken, causing bleeding from the rectal mucosa that required haemostatic clips and an epinephrine injection to obtain satisfactory haemostasis. Pathology of the sigmoid lesion revealed sigmoid infiltrating adenocarcinoma. Rectal mucosa biopsies were consistent with diffuse angiomatous lesions. Laboratory tests were unremarkable.

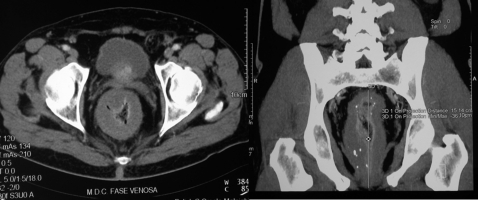

Endorectal ultrasound and a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed a significant thickness of the rectal wall, with a cluster of phleboliths, extending to the anorectal junction, with narrowing lumen. No relationship with the puborectalis muscle or the distance from the anal verge was reported. No secondary lesions were detected (fig 1).

Figure 1.

CT scan showing the extent of the diffuse cavernous haemangioma of the rectum (DCHR), circumferential size and infiltration from the upper rectum to the anorectal junction with some typical phlebolitis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Rectal bleeding is a pathognomonic symptom of many malignancies such as colorectal and anal cancers, and common benign diseases such as haemorrhoids, anal fissure or fistula.

Other benign conditions presenting with bright red blood per rectum (BRBPR) are more serious, such as inflammatory bowel disease, infectious enterocolitis, diverticular disease or colonic angiodysplasia. DCHR is a rare entity grouped with the benign lesions of the colon and rectum.

TREATMENT

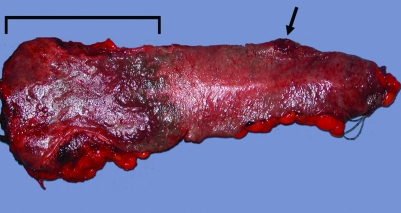

In consideration of the good sphincter function and the benign rectal disease, we planned a sphincter-sparing procedure and performed a low anterior resection of the rectosigmoid colon with hand-sewn transanal colo-anal anastomosis and loop ileostomy. The postoperative period was uneventful except for the presence of a prolonged ileus, which resolved spontaneously. Pathology report confirmed the presence of a sigmoid adenocarcinoma G2 pT3 N0 M0 (on the tumour, node, metastases (TNM) system) and a giant cavernous haemangioma extending from the rectosigmoid junction to the lower rectum, with infiltration of the distal margin (fig 2). No evidence of malignancy was detected in the rectum.

Figure 2.

Arrow: the ulcerated polypoid lesion, infiltrating adenocarcinoma; line: macroscopic extension of the transmural haemangioma. The giant haemangioma infiltrates the distal margin of resection.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

On follow-up the patient reported tenesmus and bleeding from rectum. Rectal examination showed a leakage of necrotic haemorrhagic fluid. Clinical examination was otherwise unremarkable. Persistent bleeding discharge from the rectum and stenosis of the colo-anal anastomosis was detected. The patient was scheduled for a new operation. A colo-anal anastomosis takedown, ileostomy closure with end colostomy in the left lower quadrant was performed. The anal stump was left in situ in order to spare the patient a potential perineal wound complication.

The postoperative period was uneventful. The pathology report showed colonic tissue surrounded by chronic inflammation at the anastomotic site. At follow-up the patient had repeated red blood discharge staining his underwear. Exploration of the anal canal confirmed the bloody fluid leakage. The patient also reported that this condition was making his daily quality of life extremely poor. He was readmitted for perineal excision of the retained anal stump. Pathology of the anal canal showed a giant perianal haemangioma surrounding the whole circumference of the anal canal from the top of the specimen to the perianal skin. The perianal derma was disease free. At 1 year after the last procedure the patient has completely recovered, the stoma is well functioning and the perineal wound is completely healed. No signs or symptoms were reported at the last surgical examination.

DISCUSSION

The clinical history of our patient clearly reveals longstanding rectal bleeding misdiagnosed as haemorrhoidal disease.

Investigations usually involve a plain abdominal roentgenogram, which can reveal the pathognomonic cluster of phleboliths, helical CT scan,4 transrectal ultrasonography or MRI5 detecting a varying range of transmural thickening commonly associated with this condition.

Other supplementary radiological techniques such as barium enema and upper gastrointestinal follow-through should be performed to rule out diffuse intestinal haemangiomatosis (stomach, small intestine and colon).6 Because of the well described extraintestinal involvement the pelvic cavity (bladder and uterus), spleen, liver, vertebral spine, skin and soft tissue must also be investigated to exclude Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome and variants thereof.7,8 The differential diagnosis includes benign and malignant masses, inflammatory and infectious disorders.9 Most authors do not advise biopsy collection during endoscopy, since imaging is sufficient for an exact diagnosis and the risk of bleeding is not negligible.10,11 Histologically, cavernous haemangiomas are composed of numerous dilated, thin-walled, irregular blood-filled spaces located within the mucosa and submucosa, sometimes extending through the muscular layer to the serosa.9 The treatment of choice for patients who are symptomatic is complete surgical resection.12,13 In the case of rectal haemangioma, some authors suggest a low anterior resection with minimal rectal cuff left in place, extensive rectal mucosectomy and colo-anal pull-through for low rectal lesions.4,14,15

LEARNING POINTS

A careful preoperative evaluation of the relationship between the cavernous haemangioma and the rectum/anal canal is required before surgery.

MRI to assess diffuse cavernous haemangioma of the rectum (DCHR) extension from the circumferential margin and anal canal could be of value in order to plan the most appropriate surgical procedure.

Do not perform biopsies during endoscopy, since imaging is sufficient for an exact diagnosis and the risk of bleeding is not negligible.

Other supplementary investigations should be performed to rule out diffuse intestinal haemangiomatosis and extraintestinal involvement.

An abdominoperineal resection is the best surgical choice in adult older patients with extensive haemangioma surrounding the anal canal.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Enzo Piccinini Foundation for its support and friendship.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pohlen U, Kroesen AJ, Berger G, et al. Diagnostics and surgical treatment strategy for rectal cavernous hemangiomas based on three case examples. Int J Colorectal Dis 1999; 14: 300–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yorozuya K, Watanabe M, Hasegawa H, et al. Diffuse caverous hemangioma of the rectum: report of a case. Surg Today 2003; 33: 309–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demircan O, Sonnmetz H, Zeren S, et al. Diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum and sigmoid colon. Dig Surg 1998; 15: 713–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aylword CA, Orangio GR, Lucas GW, et al. Diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectosigmoid-CT scan: a new diagnostic modality, and surgical mangement using sphincter saving procedures. Dis Colon Rectum 1988; 31: 797–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Djouhri H, Arrive L, Bouras T, et al. MR imaging of diffuse cavernous hemangioma of rectosigmoid colon. Am J Roentgenol 1998; 171: 413–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hervìas D, Turriòn JP, Herrera M, et al. Diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum: an atypical cause of rectal bleeding. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004; 96: 346–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobozy BM, Rockey DC. Diffuse colonic hemangiomatosis. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 60: 799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Topalak Ö, Gönen C, Obuz F, et al. Diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectosigmoid colon with extraintestinal involvement. Turk J Gastroenterol 2006; 17: 308–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu RM, Horton KM, Fishman EK. Diffuse cavernous hemangiomatosis of the colon: findings on three-dimensional CT colonography. Tech Coloproctol 2005; 9: 145–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terence CF, Tan MD, Wang JY. Diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum complicated by invasion of pelvic structures: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41: 1065–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka N, Onda M, Furukawa K, et al. Diffuse cavernous haemangioma of the rectum. Eur J Surgery 1999; 165: 280–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coppa GF, Eng K, Localio SA. Surgical menagement of diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the colon, rectum and anus. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1984; 159: 17–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang CH. Sphincter-saving procedure for treatment of diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum and sigmoid colon. Dis Colon Rectum 1985; 28: 604–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takamatsu H, Akiyama H, Noguchi H, et al. Endorectal pull-through operation for diffuse cavernous hemangiomatosis of the sigmoid colon, rectum and anus. Eur J Pediatric Surgery 1992; 2: 245–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan TC, Wang JY, Cheung YC, et al. Diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum complicated by invasion of pelvic structures. Report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41: 1062–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]