Abstract

Emphysematous cystitis is an uncommon condition characterised by the presence of gas in the bladder. It is an infection caused by gas forming organisms, usually in elderly women with a background of diabetes mellitus. The presentation is variable, however with increasing use of imaging more cases are being diagnosed in asymptomatic patients. Routine cross-sectional imaging is not advocated for specific diagnosis but its role in accurate assessment of the severity of the condition cannot be overlooked. As the mode and duration of follow-up in incidentally detected cases has not been addressed in the literature, follow-up should be tailored individually depending upon the severity and response to treatment. We describe two such incidentally detected cases of emphysematous cystitis in elderly diabetic patients and present a review of the literature. The triad of treatment is adequate control of diabetes, antibiotics and bladder drainage. One patient died in the hospital, while the other underwent a flexible cystoscopy 6 weeks later which was normal.

Background

A diagnosis of emphysematous cystitis carries a high mortality and morbidity rate, but it is a rare finding and cross-sectional imaging is necessary for accurate assessment. In particular, imaging should not be delayed in septic, diabetic and elderly patients. Our cases exemplify the usefulness of cross-sectional imaging in assessing the severity of the condition and treating it. The cases also raise an important question as regards the nature of the follow-up in asymptomatic incidental discovery of the disease, since the air takes time to be absorbed. Is it a symptom or a radiological diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI)?

Case presentation

Case report 1

An 84-year-old man complaining of progressive weight loss of 1-year duration underwent an ultrasound scan of his abdomen organised by his general practitioner. No abnormality was reported. A month later he was admitted to hospital under the general physicians with the same complaint. There were no other symptoms. His background problems included myasthenia gravis (on steroids), non-insulin dependent diabetes, and ischaemic heart disease; he had undergone coronary bypass grafting in the past. He was also known have chronic atrial fibrillation with NYHA class III/IV heart failure.

At admission, physical examination was unremarkable. Baseline tests demonstrated a serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 18 mg/l, serum white cell count (WCC) of 10.8×109/l and the rest of the blood investigations within normal limits. A CT scan organised to investigate weight loss showed gas within left lateral bladder wall, in the bladder lumen and in extraperitoneal space anterior to the bladder wall (figure 1A–C). Inadvertent incomplete scanning of the upper scrotum highlighted an enhancing swelling posterior to the left testis measuring 3 cm in diameter (figure 2).

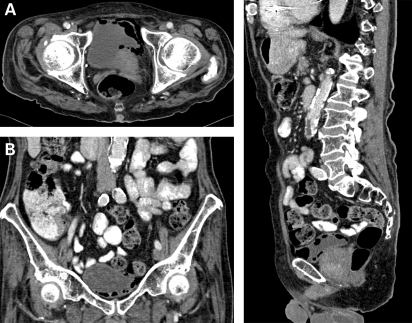

Figure 1.

(A) Horizontal CT slice showing gas in the bladder. (B) Coronal CT slice showing air in the bladder. (C) Sagittal CT slice showing air in the bladder.

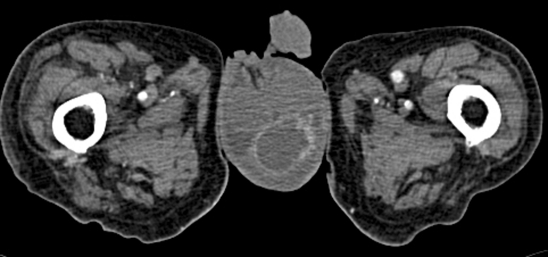

Figure 2.

CT showing scrotal abscess.

A specific urological assessment showed a 40 g benign and non-tender prostate. Scrotal examination revealed clinical signs of left epididymo-orchitis. Urinalysis revealed a sterile pyuria (54 WCC per hpf). The patient was commenced on oral ciprofloxacin, catheterised and treated conservatively. Insulin therapy was instigated due to fluctuations in his blood sugar levels. The inflammatory markers (CRP 38 mg/l, WCC 14.7×109/l) showed a only once slight rise in the apyrexial patient. Urine and blood cultures grew Klebsiella aerogenes sensitive to meropenem and imipenem only, suggestive of an extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) infection. A scrotal ultrasound scan demonstrated a hyperechoic and heterogenous mass in keeping with a scrotal abscess (figure 3). An urgent contrast CT scan with 3D reconstruction showed that the emphysematous cystitis had progressed to involve the whole bladder wall (figure 4A–C). The upper tracts were normal and there was no communication between the colon and the bladder. The patient underwent an urgent scrotal exploration and 250 ml of foul smelling pus, arising from an intratesticular abscess, was evacuated. An orchidectomy was performed. Rigid cystoscopy showed multiple bullae in the mucosa within the bladder. Pus culture from the abscess grew Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) sensitive to vancomycin and gentamicin. The antibiotics were changed accordingly. In spite of antibiotic therapy, the patient continued to deteriorate and died peacefully a fortnight after his orchidectomy. During the entire course of his illness, he remained apyrexial with a minimal elevation of his serum inflammatory markers.

Figure 3.

Ultrasound scan of the scrotum showing heterogenous and predominantly hypoechoic areas in the left scrotum suggestive of abscess.

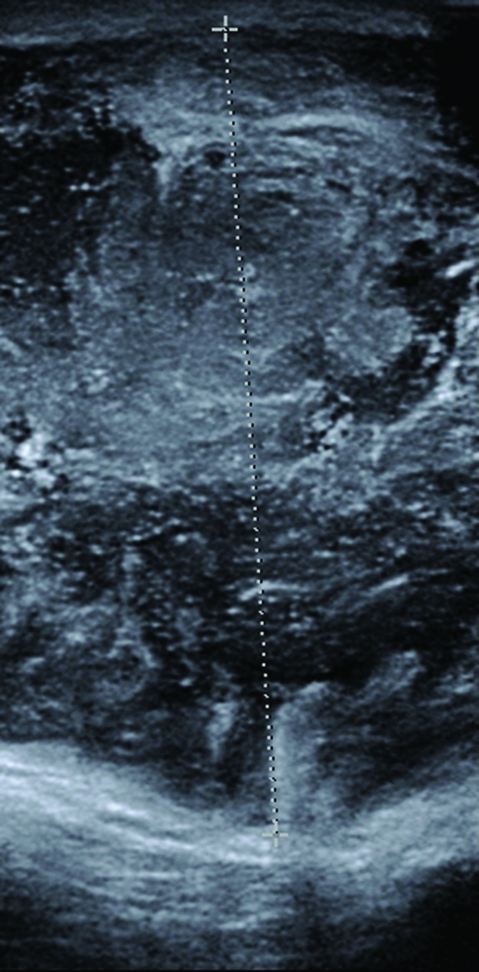

Figure 4.

(A) Horizontal CT slice showing increased emphysema. (B) Coronal CT slice showing increased emphysema. (C) Sagittal CT slice showing increased emphysema.

Case report 2

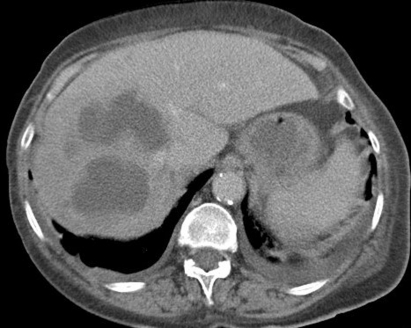

An 80-year-old woman with background problems of hypertension, insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, myocardial infarction and left ventricular failure was admitted for an elective angioplasty of her right lower limb. Following the procedure she complained of pain in the right flank for which she underwent an ultrasound scan that showed a liver abscess which was confirmed by an abdominal CT scan (figure 5). The CT scan also picked up extensive gas in the wall of the bladder, consistent with emphysematous cystitis (figure 6), although the patient was asymptomatic. Initial management included commencement of parenteral antibiotics, appropriate diabetes control, percutaneous drainage of the liver abscess and bladder catheterisation. Urine showed the presence of coliforms sensitive to trimethoprim, nitrofurantoin and cefalexin. The pus from the liver abscess showed an anaerobic growth sensitive to metronidazole. The patient quickly improved and her catheter was removed following a normal bladder wall on ultrasound scan. A flexible cystoscopy performed 6 weeks later was normal.

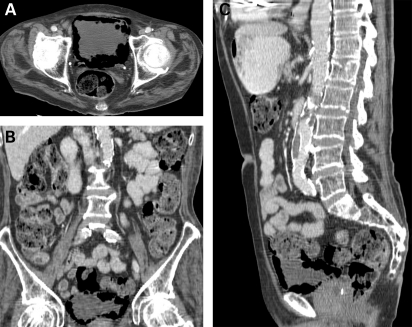

Figure 5.

CT showing liver abscess.

Figure 6.

Incidental emphysematous cystitis.

Treatment

The triad of treatment is adequate control of diabetes, antibiotics and bladder drainage.

Outcome and follow-up

One of the patients died in the hospital, while the other patient underwent a flexible cystoscopy 6 weeks later which was normal.

Discussion

Emphysematous conditions are defined by the presence of air in the wall or in lumen of a hollow organ. Emphysematous cystitis is an acute inflammation of the bladder and is characterised by gas within the lumen and its wall. The true incidence of emphysematous cystitis is unknown. Since the initial review by Thomas et al1 in 2007 about 20 case reports have been indexed in PubMed under the keyword “emphysematous cystitis”. The seemingly increased incidence of emphysematous cystitis may be due to an increasing use of imaging and many cases are diagnosed as incidental findings, as demonstrated in our cases. Nevertheless, the possibility of under-diagnosis still remains given that imaging is not routinely performed for UTI.1 In case report 1, the disease progressed rapidly despite aggressive treatment, while case report 2 had a favourable outcome, although the findings were incidental in both cases. Emphysematous cystitis is frequently associated with elderly women, usually between the sixth and eighth decades. Diabetes mellitus is the most common predisposing factor identified in all reviews.1–3 UTI and bacteriuria are more common in women with diabetes mellitus than those without diabetes mellitus.4 Factors such as impaired bladder emptying, indwelling catheters, instrumentation and urinary tract stones, especially in the presence of diabetes mellitus, can predispose to UTI and emphysematous cystitis. Stapleton recommends treating UTI in diabetes mellitus patients as a complicated UTI because such patients also have an increased prevalence of anatomic and functional abnormalities.4 Diabetic nephropathy and secondary bladder dysfunction combined with lowered immunity increase the risk of a complicated UTI.1–4 Although case reports describing emphysematous cystitis being diagnosed in dialysis and post-transplant patients have been published, whether these conditions are causative needs to be proven. The only common factor seems to be immunosuppression among these patients. The most commonly identified gas forming organisms are Escherichia coli and Klebsiella.1–4 However, non-gas forming organisms, such as Enterobacter and various fungal species like Candida, have also been isolated.1–3 The exact pathogenesis is not understood, but a multifactorial combination of gas producing organisms, high glucose concentration (glucosuria), lowered immunity, decreased tissue perfusion and impaired catabolism has been suggested.1 Gas forming organisms produce carbon dioxide at lowered pH by fermenting local glucose,3 but this does not explain why emphysematous cystitis is seen in non-diabetic patients and where non-gas forming organisms are isolated. A plausible theory is that urinary albumin, lactose and tissue proteins act as substrates for gas forming organisms.1,3 Rapid catabolism leading to production of gas coupled with impaired absorption leading to accumulation of gas causing local infarction has been suggested to explain the pathogenesis.3 Bacterial virulence may play a limited role in the development of emphysematous pyelonephritis, while poorly controlled diabetes mellitus is believed to be the major host factor.5 Case reports have also described air in the hepatic veins and inferior vena cava in association with emphysematous cystitis, but again the pathogenesis is not understood.6,7

The presentation of emphysematous cystitis may vary from the asymptomatic patient to a patient with overt sepsis to peritonitis secondary to bladder necrosis as shown recently in a case report.2,3,8 The diagnosis of emphysematous cystitis is often made radiologically but may also be made during cystoscopy, laparotomy or at autopsy.1–3

Plain x-ray of the kidney, ureters and bladder (KUB) although sensitive enough lacks specificity. It remains the most common initial diagnostic modality in all reports. Air fluid levels in the bladder or a typical “cobblestone” or “beaded necklace” appearance may be seen, although the presence of bowel gas can be a confounding feature.9 Ultrasound scan has a low sensitivity but may demonstrate indirect signs like diffuse bladder wall thickening or increased echogenicity.3,9 It may be useful for serial monitoring in patients showing clinical improvement and those who cannot have CT for any reason. CT is the most specific modality and will also diagnose other pathologies such as diverticular abscess, neoplasms, vesicocolic fistula, ascending infection and scrotal abscess.1–3 The value of serial CT to monitor patient progress is well exemplified by our case report 1 and the algorithm suggested by Mokabberi et al which emphasises adequate drainage, serial radiology and use of antibiotics, appears reasonable.2 However, it does not answer the question of duration of antibiotic use and serial radiology in asymptomatic or improving patients as gas may take some time to be absorbed. Cystoscopy is not routinely indicated but may provide information regarding outlet obstruction or the presence of enteric fistulas.1 The management of emphysematous cystitis is based on patient symptoms, but parenteral antibiotic therapy, bladder drainage and good control of the hyperglycaemic state form the triad of treatment. Antibiotics should be based on sensitivities, although initially broad spectrum antibiotics can be started empirically according to local protocol.1–4 Tseng et al5 found that poor glycaemic control and urinary tract decompression are the host factors predisposing to emphysematous pyelonephritis. Patients not responding to medical management may require serial CT scans to exclude conditions such as necrotising infections which may require surgical management such as partial or total cystectomy, laparotomy for bowel diversion, etc. Overall, 10%–19% of medically managed patients require surgical intervention.1,3 Thomas et al recently reported a 7% mortality rate for emphysematous cystitis alone and 14% for combined emphysematous infections of the urinary tract,1 whereas Grupper et al reported a 19% complication rate in their series.3

In conclusion, emphysematous cystitis is an uncommon condition, which can present in a variety of ways. The condition is almost certainly under-diagnosed as not all patients undergo radiological investigation for UTI and many cases are increasingly discovered following radiological investigation for an entirely different pathology. We do not routinely advocate the use of expensive imaging in every suspected UTI, however in septic, diabetic and elderly patients it should be considered in order to minimise complications. A delay in diagnosis can potentially result in life threatening complications, and a high index of suspicion is required, especially when treating a UTI in elderly diabetic patient. Prompt medical therapy will usually suffice, but patients require careful monitoring for the development of complications. The value of good control of diabetic status and the role of serial CT scanning in assessing the extent and severity of infection cannot be overemphasised.

Learning points

Cross-sectional imaging is not routinely advocated in urinary tract infections, but must not be delayed in septic, diabetic and elderly patients.

The incidental discovery of emphysematous cystitis on radiological investigation raises the question whether it is a symptom or just a radiological diagnosis.

Empysematous cystitis must be treated aggressively as a complicated urinary tract infection with antibiotics, good glycaemia control and adequate drainage of the bladder.

Radiological follow-up and duration of antibiotic therapy must be tailored to individual cases.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thomas AA, Lane BR, Thomas AZ, et al. Emphysematous cystitis: a review of 135 cases. BJU Int 2007; 100: 17–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokabberi R, Ravakhah K. Emphysematous urinary tract infections: diagnosis, treatment and survival (case review series). Am J Med Sci 2007; 333: 111–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grupper M, Kravtsov A, Potasman I. Emphysematous cystitis: illustrative case report and review of the literature. Medicine 2007; 86: 47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stapleton A. Urinary tract infections in patients with diabetes. Am J Med 2002; 113(Suppl 1A): 80S–84S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tseng CC, Wu JJ, Wang MC, et al. Host and bacterial virulence factors predisposing to emphysematous pyelonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 46: 432–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen KW, Huang JJ, Wu MH, et al. Gas in hepatic veins: a rare and critical presentation of emphysematous pyelonephritis. J Urol 1994; 151: 125–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nozu T. Emphysematous cystitis with air bubbles in the inferior vena cava. Int J Urol 2008; 15: 947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rindom AB, Gudnason HM, Thind PO. Emphysematous cystitis with total necrotization of the bladder. Ugeskr Laeger 2008; 170: 3876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grayson DE, Abbott RM, Levy AD, et al. Emphysematous infections of the abdomen and pelvis: a pictorial review. Radiographics 2002; 22: 543–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]