Abstract

We present a rare case of an amelanotic melanoma of unknown primary presenting with cervical lymphadenopathy. A 20-year-old man presented with large left sided neck lump, associated dysphagia and weight loss. Examination revealed a hard mass in the left posterior triangle of neck and sacral sensory loss. Fine needle aspiration cytology of the mass suggested a poorly differentiated carcinoma. Computed tomography showed a left sided, 8×13 cm cervical mass with liver, lung and bony metastases. Histological examination of the lymph nodal mass confirmed the diagnosis of a metastatic amelanotic melanoma. The patient was treated with glucocorticoids, radiation therapy for the sacral bony deposit, and chemotherapy. Despite an initial reduction of his target lesions, his condition subsequently deteriorated and he died 4 months after diagnosis.

BACKGROUND

Melanoma currently is the sixth most common cancer in the developed countries. Up to 6% of these may present with metastases without a known primary.1,2

The incidence of melanoma has more than tripled in the Caucasian population during the last 20 years.

Melanomas can present with cervical lymphadenopathy.

Urgent diagnosis and aggressive treatment may prolong survival.

This case report highlights the challenges in identifying the primary tumour with a metastatic melanoma.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 20-year-old Caucasian male presented to the department of head and neck surgery at Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley with a progressively enlarging, large left sided neck lump with associated dysphagia and significant weight loss. He also had lower urinary tract symptoms. He had noticed the mass 10 months ago but did not seek treatment due to an aversion to hospitals. He had undergone tonsillectomy at the age of 5 years. He had been a moderate smoker for the past few years. Examination revealed a 5×6 cm hard mass in the left posterior triangle of neck. Neurological examination revealed sensory loss in the right S1 and S2 dermatomes. There was no significant family history of malignancy.

INVESTIGATIONS

Computed tomography (CT) scan showed a left sided, 8×13 cm neck mass, increased soft tissue in the left tonsillar fossa measuring around 2 cm, as well as multiple lung, liver and bony metastases (figs 1 and 2). There was a 5 cm bony metastases anterior to the right sacral ala presumably causing the urinary symptoms. There was no mediastinal or abdominal lymphadenopathy.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography (CT) scan showing thickening of left tonsillar fossa.

Figure 2.

CT scan showing a large left sided level V lymph nodal mass.

Fine needle aspiration cytology of the neck mass showed highly cellular smears, with pleomorphic cells, abundant cytoplasm, eccentric nuclei, and prominent nucleoli with anisokaryosis suggesting a poorly differentiated or anaplastic carcinoma.

Multiple biopsies from the nasopharynx, oropharynx, base of the tongue and pyriform fossae and tonsillar fossae did not show any evidence of tumour.

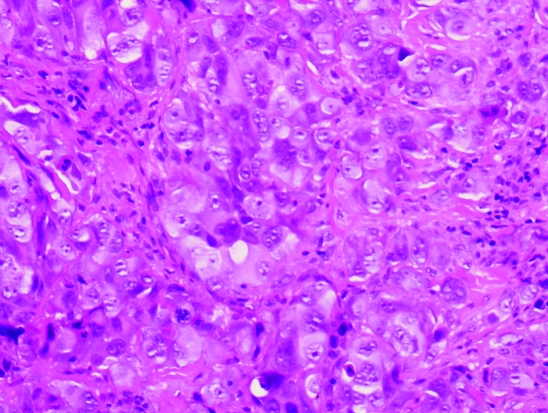

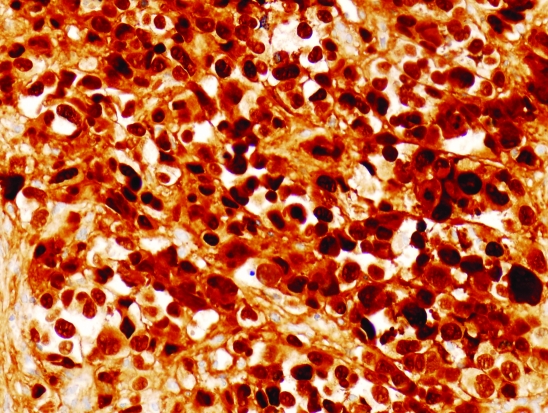

Histological examination of the cervical lymph node showed fibro-connective tissue extensively infiltrated by a poorly differentiated neoplasm formed of sheets and solid nests of highly atypical large, rounded and polyhedral cells with epithelioid features, large vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (fig 3). Mitoses were abundant with many cells showing bizarre hyperchromatic smudged nuclei. The tumour cells showed strong staining for melanoma markers—S100 protein (fig 4) and Melan-A—but were negative for epithelial markers—pancytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen. No melanin pigment could be identified by the haematoxylin and eosin or by the Masson Fontana stain leading to a diagnosis of a metastatic amelanotic melanoma.

Figure 3.

Large nests of atypical epithelioid cells with markedly pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm. No melanin pigment is identified in the cytoplasm. Haematoxylin and eosin stain ×20.

Figure 4.

Tumour cells showing crisp staining for S100 protein ×20.

TREATMENT

The patient was referred to the regional cancer centre at Royal Wolverhampton Hospitals NHS Trust and was treated with glucocorticoids, chemotherapy and radiation therapy for the sacral bony deposit. He received 20 Gray in five fractions to his sacral lesion to reduce the risk of significant neurological complications. He was then commenced on palliative chemotherapy with the CVD regimen (cisplatin, vinblastine and dacarbazine).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Despite an initial minor response with a reduction of his target lesions by 31%, his condition subsequently deteriorated and he died 4 months after diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Melanomas of an unknown primary (MUP) have been reported to have an incidence of 2–6% of all melanomas.1,2 Presentation with a cervical or parotid lump is rare.3 In the various series published, the incidence of amelanotic melanoma of unknown primary has not been described.

Das Gupta et al4 have proposed a widely accepted definition of MUP. Melanoma of unknown primary is excluded if there is:

a history of orbital enucleation or exenteration

a history of skin lesion removed, if slides not available for review

presence of scar of previous local treatment in skin area drained by involved lymphatic basin

a lack of thorough physical examination including ophthalmic and genital examination.

Our patient fits the category of MUP according to the above criteria. There are various aetiological theories for MUP. These are: (1) an antecedent, unrecognised spontaneously regressed primary melanoma; (2) a previously excised or histologically misdiagnosed melanoma; (3) a concurrent, clinically unrecognised melanoma; and (4) de novo malignant transformation of an errant melanocyte at lymph node or visceral site.3

The first and the third hypotheses could explain the absence of a primary lesion in our patient. The presence of an amelanotic primary melanoma can be difficult to note, especially in Caucasians. Regression of cutaneous melanoma is reported in 20% of melanoma patients.3 Anderson et al have previously described a case with similar presentation in 1981.5

MUP patients with lymph nodal metastases have a better prognosis than lymph node metastasis from a known primary melanoma.6 However, in the presence of widespread visceral metastases, the median survival among patients with MUP has been reported to be up to 1.1 years.1,2 Thus the goal of treatment should be palliative rather than curative.

LEARNING POINTS

Melanoma currently is the sixth most common cancer in developed countries; its incidence has more than tripled in the Caucasian population during the last 20 years.

Metastatic melanoma carries a poor prognosis, but early diagnosis and aggressive treatment may improve prognosis.

Assessment of a metastatic melanoma can be challenging.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Katz KA, Jonasch E, Hodi FS, et al. Melanoma of unknown primary: experience at Massachusetts General Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Melanoma Res 2005; 15: 77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anbari KK, Schuchter LM, Bucky LP, et al. Melanoma of unknown primary site: presentation, treatment, and prognosis-a single institution study. University of Pennsylvania Pigmented Lesion Study Group. Cancer 1997; 79: 1816–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balm AJ, Kroon BB, Hilgers FJ, et al. Lymph node metastasis in the neck and parotid gland from an unknown primary melanoma. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 1994; 19: 161–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das Gupta T, Bowen L, Berg JW. Malignant melanoma of unknown primary origin. Surg Gynecol Obst 1963; 117: 341–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson CW, Stevens MH, Moatamed F. Electron microscopy and L-dopa reaction in the evaluation of an unusual amelanotic malignant melanoma of the neck. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1981; 89:594–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cormier JN, Xing Y, Feng L, et al. Metastatic melanoma to lymph nodes in patients with unknown primary sites. Cancer 2006; 106: 2012–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]