Abstract

A 22-year-old female patient was admitted to our clinic after both clinical and laboratory findings suggested hyperthyroidism. At pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we detected a substernal goitre with lobulated outlines at the inferior of the right lobe that extended 5 cm inferior to the carina. The thyroid mass extended to the mediastinum and was totally extracted by cervical incision. Postoperatively, a residual thyroid mass of 8.5×9×10 cm in size, was detected on MRI at the median part of the anterior mediastinum. The isolated mediastinal thyroid mass was then extracted by sternotomy. We believe that, because of the close anatomical relationship between the thyroid tissue extending cervically and the mass detected in the mediastinum, the mediastinal mass might have developed from the cervical thyroid tissue residues by pushing the cervical thyroid or it might have mechanically entered the mediastinum.

BACKGROUND

Despite the controversy about the definition of substernal or intrathoracic goitre in the literature, the most commonly accepted definition is the presence of thyroid tissue below the manubriosternal junction either clinically or radiologically.1 It may be classified as primary or secondary according to the tissue it originates from. Primary substernal goitre (primary intrathoracic goitre) develops with the enlargement of ectopic mediastinal thyroid tissue. These goitres are mainly intrathoracic and have no connection with the cervical thyroid gland; they derive their blood supply from intrathoracic vessels and drain into the veins in the chest. Secondary substernal goitres (secondary intrathoracic goitre) develop with the extension of thyroid tissue, normally located in the neck, into the superior mediastinum. With the effects of the negative mediastinal pressure on inspiration, motion during swallowing and the gravity, the tissue follows the fascial planes downward in the neck, and settles down in the mediastinum. These tissues derive their blood supply from the inferior and the superior thyroid arteries. The majority of the substernal goitres are secondary; only 1% of them are primary.2

The differential diagnosis of primary and secondary goitre may be challenging. In our case of a substernal goitre, our target of discussion was the tissue, where it originated from.

CASE REPORT

Presenting features

A 22-year-old woman was admitted to our clinic complaining of a swelling of the neck, difficulty breathing, distress, nervousness, insomnia and fatigue for 1.5 years. Her physical examination revealed, multiple nodules extending to the level of clavicula in the right lobe of the thyroid.

Investigations

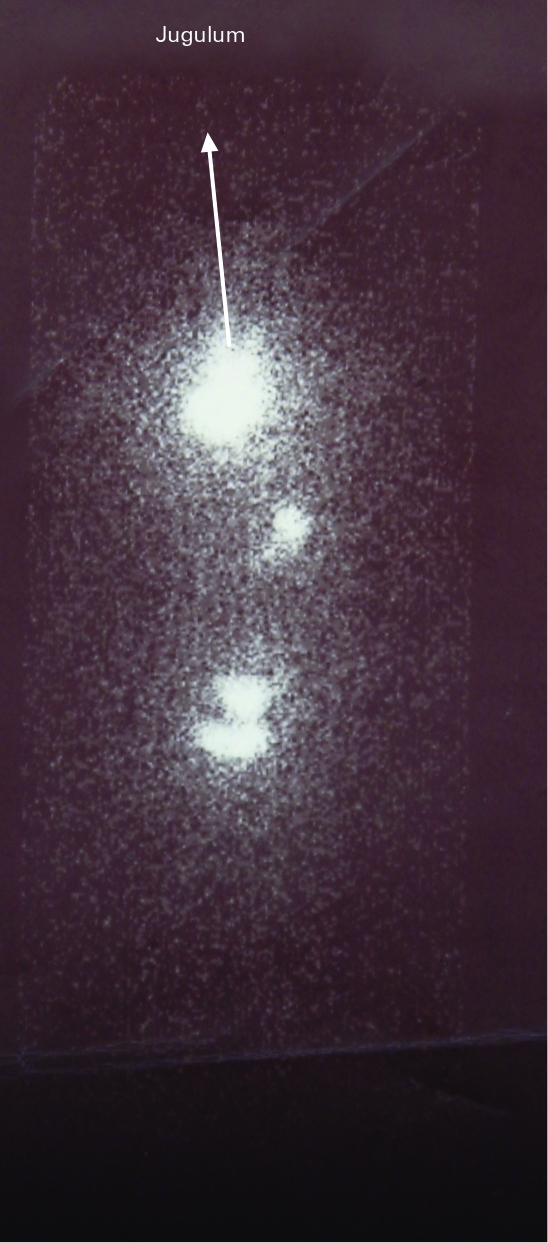

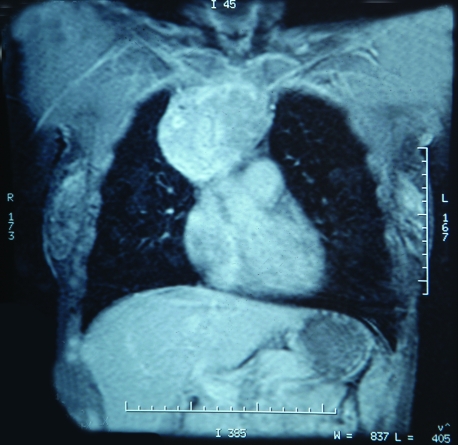

Hyperthyroidism was detected by thyroid functioning tests: triiodothyronine 241 ng/dl (80–200), free thyroxine 2.68 ng/dl (0.93–1.7), thyroid-stimulating hormone <0.005 uIU/ml. Ultrasound of the thyroid showed the left lobe to be normal in size and structure, whereas the right lobe and the isthmus, there were many heterogeneous nodules and hypoechoic large nodular structure at the inferior of the right lobe extending to the retrosternal region. At the thyroid scintigraphy (iodine-131 uptake test), substernal activity could be seen (fig 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck and thorax showed a lobulated mass in the thyroid gland adjacent to the inferior of the right lobe. The mass extended retrosternally 5 cm inferior to the carina in the mediastinum (fig 2). A tiny lobulation line was remarkable and found between the superior and inferior part of a section of the lesion in the thorax.

Figure 1.

Cervical and substernal (mediastinal, intrathoracic) nodular activity can be seen in thyroid scintigraphy (iodine-131 uptake test).

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the neck and thorax showed a heterogeneous mass containing fatty components in the thyroid gland adjacent to the inferior of the right lobe. The mass extended retrosternally, 5 cm inferior to the carina in the mediastinum.

Treatment

The patient was treated with propylthiouracil (300 mg/day) and propranolol (40 mg/day) and became euthyroid. After preparing the patient for a sternotomy, they underwent a cervical incision. Initially, the left lobe that did not show a substernal extension was dissected. The strap muscles were dissected on the right side from the 1/3 upper level. The right lobe extended to the left side passing the median line and extending substernally. With the protection of nervus recurrens, superior and inferior parathyroid glands, all the connections of the right lobe at the cervical region were dissected and the dissection was carried above the trachea. Blunt dissection was performed with a finger between the carotid sheath’s medial face and the thyroid gland. With gentle traction to the gland at the neck, the thyroid gland’s substernal part was delivered slowly from the cervical incision. On macroscopic examination of the specimen, it was recognised that the substernal section was taken out with the preservation of the whole thyroid capsula. The size of the right lobe was 10×8×6 cm. It was reported during the pre-operative diagnostic radiological examination that the thyroid extended 5 cm inferior to the carina; therefore, sternotomy was not performed because the right lobe with an intact capsule was totally extracted and at the extracted part’s base, the fascial entity in the mediastinum was not broken down. At pathological examination, it was also reported that the material with the intact capsule from the total thyroidectomy was a nodular goitre.

Outcome and follow-up

A postoperative MRI was done to assess residual tissue at the substernal region. A mass that showed heterogeneous contrast activity (8.5×9×10 cm in size) was evaluated as the intrathoracic component of the gland (fig 3); it was causing significant compression in the anterior mediastinum to the vena cava superior to the medial part and the arcus aorta has been displaced posteroinferiorly by the mechanical effect of the mass and the vessels originating from the arcus aorta have been displaced posteriorly. The patient’s hyperthyroidism relapsed during the first month post-operation.

Figure 3.

Rest thyroid tissue (8.5×9×10 cm) in the anterior mediastinum seen on magnetic resonance imaging after cervical thyroidectomy.

Re-operation

The patient was again treated with propylthiouracil (300 mg/day) propranolol (40 mg/day) and stabilised until she was euthyroid and a median sternotomy was performed. The mass, approximately 10 cm diameter, lobulated, with the fibrous capsule was found in the anterior mediastinum; it was getting its blood supply from the tiny parasitic vessels originating from the surrounding tissue in the mediastinum, not from a major vessel or any of the cervical vessels. The mass was totally extracted (fig 4). At the pathological examination, it was detected to be a nodular goitre with its own fibrous capsule, showing signs of hyperfunctioning. There were no complications during the postoperative period.

Figure 4.

The extracted nodular thyroid mass.

DISCUSSION

The thyroid gland develops from the endoderm at the base of the tongue (foramen caecum) and descends through the thyroglossal duct to its normal location at the thyroid cartilage. Ectopic thyroid tissue is the result of abnormal migration of the thyroid gland. An ectopic thyroid is a frequent anomaly and usually is identified along the normal route of its descent.2 According to autopsy studies, the prevalence of an ectopic thyroid is between 7% and 10%, with lingual thyroid tissue accounting for 90% of the abnormalities.3 However, ectopic thyroid tissue can also be found throughout the mediastinum. The embryological development of the thyroid parenchyma is closely associated with the aortic sac and the heart; as the heart descends into the mediastinum, it draws the thyroid gland with itself caudally and this causes the development of ectopic mediastinal thyroid tissue. True primary intrathoracic (substernal) goitres are quite rare, occurring in less than 1% of all substernal goitres.2

Sometimes isolated normal thyroid tissue residues can be coincided within the line of the thyrothymic tract below the inferior pole of the thyroid during thyroidectomy. The development of nodular change within such rest thyroid tissue might be recognised as a large thyroid nodule quite separate from and caudal to the inferior pole of the thyroid gland. Sackett et al4 evaluated the incidence and relationship to the thyroid gland of such thyroid residues at the cervical thyrothymic tract of 100 cases that were operated for thyroid disease or hyperparathyroidism. Four grades were classified according to the relationship of the thyrothymic residues (rests) with the thyroid gland:

Grade I. Thyroid rests consist of a protrusion of thyroid tissue, recognisably distinct from the lower border of the thyroid lobe in the region of the thyrothymic ligament.

Grade II. Thyroid rests include thyroid tissue lying within the thyrothymic tract and attached to the thyroid proper only by a narrow pedicle of thyroid tissue.

Grade III. Thyroid rests are similar to grade II but are attached to the thyroid gland only by a fibrovascular core.

Grade IV. Thyroid rests have no connection to the thyroid gland.

The researchers noted one or two sided thyrothymic rests in 53% patients. The majority of them were small, with 88% being <1 cm in diameter. Up to 20% of the rests were grade III and grade IV. They noted that the recognition of such isolated rests (grades III and IV), clinically, is important and the nodular growth within such rests might well be the explanation for the development for not all, but many mediastinal goitres. If such a nodule lies even further caudal, within the anterior mediastinum, it might well give rise to the isolated mediastinal or intrathoracic goitre. Besides, they mentioned that failure to recognise and remove such rests might be a cause of local recurrence of thyroid tissue, or indeed of retrosternal recurrence after presumed total thyroidectomy.4 In another study by Reeve et al5 12 such patients have presented with retrosternal recurrence after a previous total thyroidectomy and have required further surgery. Casadei et al6 detected a mediastinal thyroid mass in a patient after total thyroidectomy and defined it as a “forgotten goitre”. Basaria and Cooper7 detected an ectopic thyroid in the mediastinum and they observed that it was suspended by a thin pedicle from the left lobe. This case agrees with Sackett et al’s4 substernal (intrathoracic) goitre case that was developed from grade III thyrothymic rests. Sakorafas et al8 detected an intrathoracic ectopic thyroid tissue extending to the right posterior mediastinum. They reported that this tissue did not have a connection with the cervical thyroid and, therefore, could not be removed through cervical incision. They performed a right lateral thoracotomy. The researchers mentioned that ectopic intrathoracic thyroid tissue can be distinguished from the cervical substernal goitre with its blood supply from the mediastinum and its distinctiveness from the cervical thyroid except a thin band of connective tissue. However, the mediastinal masses that are bounded to the cervical thyroid with a thin band of connective tissue give the impression of possibly developing from the thyrothymic rests (grade III), unlike primary mediastinal thyroid rests. To date, however, apart from the study by Sacket et al,4 there is no research on the existence and incidence of normal thyroid tissue in cervical and/or mediastinal thymus. Besides this study, Spinner et al9 reported two cases with thyroid mass in the mediastinal thymus. Kousta et al10 reported a case with a thyroid nodule suiting a grade IV thyroid rest, independent from the thyroid gland at the inferior of the inferior pole. Even independent thyroid nodules below the inferior pole may be seen during thyroid operations; their relapse and role in the development of mediastinal goitre after surgery has not been evaluated in the studies above.

In our case, a mediastinal thyroid mass that was extracted by sternotomy that had no direct connection to the cervical mass and the blood supply from the mediastinal vessels fits the term “primary mediastinal goitre”. However, there was a thin facial structure between the cervical thyroid and the ectopic mediastinal thyroid tissue, and despite the fact that they are independent from each other, because of the close anatomic relation between them, they were detected as one structure with lobulated outlines on the first MRI. Therefore, we believe that the mediastinal mass developed from the grade III or IV thyrothymic rest is the same as that mentioned by Sackett et al4. This rest tissue may begin to develop a nodular character together with the nodular development in the thyroid, and with the combined effect of gravity, the weight of the mass itself and the effect of negative intrathoracic pressure, it may completely enter the mediastinum. The right lobe that was growing at the same time as this mass and pushing it mechanically into the mediastinum may also help this. We believe that the parasitic vessels appeared after the mass had entered the mediastinum, to supply nourishment for the mass. Besides, although the primary intrathoracic goitres usually have a relationship with the heart and the main large vessels anatomically, this mass did not have a direct relationship with the heart and the main mediastinal vascular structures. For this reason, this thyroid tissue in the mediastinum could have had a cervical origin; therefore, it does not fit into the definition “primary substernal goitre”.

Substernal goitres usually grow very slowly and are most commonly found in patients in their fifth or sixth decade of life.2 Hyperthyroidism is found in 15–40% of patients with substernal goitres; this finding is usually seen in older patients with a long-standing goitre.11 However, in our case the patient was only 22 years old, which is quite young for a substernal goitre. The patient also had hyperthyroidism, which is also rarely seen with a substernal goitre in this age group.

Computed tomography (CT) and MRI are the best imaging methods to evaluate intrathoracic extension of substernal goitres. These techniques provide important information about anatomo-topographic staging of substernal goitres, their relation with the surrounding structures, and the situation of the continuity between the cervical and the thoracic components of the goitre.12 In our case, even the relation of the thyroid with the other structures in the thorax and its stage were being clearly observed in the first MRI, because the thyroid tissue extending from the cervical and the mediastinal mass was in close anatomic relationship, and their margins could not be separated from each other and so was being observed as one lobulated bordered mass. In our case, the thyroid rest tissues at the mediastinum could be detected by CT or MR postoperatively, which were extracted by cervical incision.

LEARNING POINT

Thyroid masses that develop from the thyrothymic rests may enter the mediastinum and present as primary substernal goitres with the cervical thyroid pushing and/or by their own weight under gravity.

To minimise the possibility of persistent thyroid disease; during the first operation of substernal goitres as in our case, a nodule arising from these rests at the inferior border of the thyroid gland should be taken into account.

Even if the cervically extracted, low-lying, lobulated bordered, substernal mass’s capsule is intact, if there is a difference in size between the preoperative image and the extracted mass, the second thyroidal mass remaining in the mediastinum should be investigated by postoperative MRI or CT.

The choice of treatment for mediastinal thyroid masses that were diagnosed symptomatically, both originating from ectopic mediastinal or ectopic cervical tissue, is surgery. However, the mediastinal masses that originate from cervical thymic rests are important because these primary mediastinal thyroid masses are rare.

Because thyrothymic thyroid rests are relatively common, they possibly increase the rate of mediastinal recurrence, compared with ectopic mediastinal thyroid tissues. However, we believe that it is important to be aware of the presence of the cervical rests during thyroidectomy in order to decrease the possibility of leaving rest thyroid tissue and to prevent mediastinal recurrence.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hsu B, Reeve TS, Guinea AI, et al. Recurrent substernal nodular goiter: incidence and management. Surgery 1996; 120: 1072–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mack E. Management of patients with substernal goiters. Surg Clin N Am 1995; 75: 377–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neinas FW, Gorman CA, Devine KD, et al. Lingual thyroid. Clinical characteristics of 15 cases. Ann Intern Med 1973; 79: 205–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sackett WR, Reeve TS, Barraclough B, et al. Thyrothymic thyroid rests: incidence and relationship to the thyroid gland. J Am Coll Surg 2002; 195: 635–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeve TS, Delbridge L, Brady P, et al. Secondary thyroidectomy: a twenty-year experience. World J Surg 1988; 12: 449–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casadei R, Perenze B, Calculli L, et al. “Forgotten” goiter: clinical case and review of the literature. Chir Ital 2002; 54: 855–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basaria S, Cooper DS. Graves’ disease and recurrent ectopic thyroid tissue. Thyroid 1999; 9: 1261–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakorafas GH, Vlachos A, Tolumis G, et al. Ectopic intrathoracic thyroid: case report. Mt Sinai J Med 2004; 71: 131–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spinner RJ, Moore KL, Gottfried MR, Lowe JE, Sabiston DC., Jr Thoracic intrathymic thyroid. Ann Surg 1994; 220: 91–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kousta E, Konstantinidis K, Michalakis C, et al. Ectopic thyroid tissue in the lower neck with a coexisting normally located multinodular goiter and brief literature review. Hormones (Athens) 2005; 4: 231–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sitges-Serra A, Sancho JJ. Surgical management of recurrent and intrathoracic goiters. : Clark OH, Duh Q-Y, Kebedew E, eds. Textbook of Endocrine Surgery, 2nd edn Philadelphia: W.B Saunders, 2005: 304–17 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makeieff M, Marlier F, Khudjadze M, et al. Substernal goiter. Report of 212 cases. Ann Chir 2000; 125: 18–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]