Abstract

Cervical injury is a serious and often fatal complication of ankylosing spondylitis in the setting of minor trauma. This case report describes a 51-year-old woman with ankylosing spondylitis and a minor trauma who developed severe bradycardia during positioning for x ray. Further diagnostic revealed a hyperextensive fracture of C4 with fragments compressing the cervical medulla. The woman subsequently died from hypoxic brain damage. Reviewing the literature, a high alertness in ankylosing spondylitis and minor trauma with neck immobilisation is emphasised, early diagnosis using cervical spine computed tomography is essential to a favourable outcome, and the mechanism of bradycardia in cervical trauma is discussed.

BACKGROUND

This case is important as it demonstrates how a blunt injury may have fatal consequences if some easy and basic rules are disregarded.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 51-year-old woman with ankylosing spondylitis fell down after drinking some mulled wine. Arriving at a rural hospital, she was alert without any major deficits. During positioning for cervical x ray she suddenly developed bradycardia and had to be resuscitated. For further diagnostic procedures, she was transferred to a teaching hospital.

INVESTIGATIONS

Computed tomography (CT) of the cervical spine showed, in addition to the typical features of ankylosing spondylitis with ossified ligaments, a hyperextensive fracture of C4 with fragments compressing the cervical medulla (figs 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Cervical computed tomography (CT) scan (sagittal view) showing hyperextensive fracture of C4 (arrow).

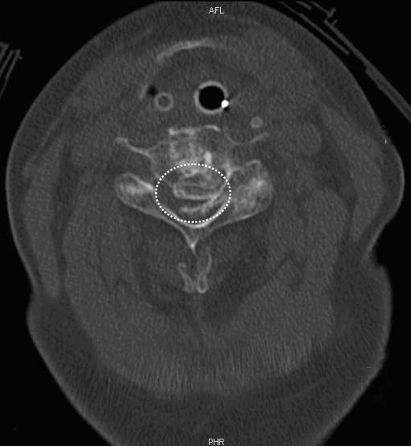

Figure 2.

Cervical CT scan (axial view) with fragments filling the cervical canal and compressing the cervical medulla (dotted circle = original cervical canal).

TREATMENT

A halo fixator was used for stabilisation. Postoperatively, several episodes of bradycardia and hypotension occurred which resolved with administration of atropine.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient stayed comatose and developed severe post-hypoxic myoclonus. As the brain scan showed early signs of hypoxic damage and a notably raised neuron specific enolase indicated poor prognosis, further treatment was limited. Finally, she died as a result of cardiovascular instability with recurrent bradycardia and asystole.

DISCUSSION

Longstanding ankylosing spondylitis may predispose to serious cervical injury in the setting of minor trauma which results from the combination of kyphosis, stiffness and osteoporotic bone quality of the spine in ankylosing spondylitis.1,2 In more than 50% of the cases the precipitating trauma is minor in nature, and unlikely to result in the fracture of a normal spine.2 The risk of sustaining neurological deficits is higher than average and mortality is twice that observed with a similar fracture involving normal spines.2 Several cases with fatal outcome after minor falls have been described.2–4 Due to the potentially catastrophic neurological complications the importance of routine cervical spine immobilisation in all trauma patients is recommended.5

In a recent review of spinal cord injury in patients with ankylosing spondylitis, most of the injuries resulted from falls. These patients showed a similar clinical pattern, most of them being able to walk immediately after the fall but subsequently deteriorated for various reasons. Patients with an ankylosed cervical spine are normally unable to see the ceiling when lying supine because of cervicothoracic kyphosis, and use pillows to support their head. However, the required extension of the ankylosed kyphotic cervical spine for radiological procedures may result in severe neurological deficit, as it happened in the present case. Therefore, cervical spine alignment in a similar flexed position is essential during immobilisation or imaging. The authors suggest using medical alert cards for patients with ankylosing spondylitis so that appropriate precautions can be instituted by the emergency services.6

Neurological deficits are often subtle on initial presentation, resulting in many injuries being missed because of a low index of suspicion and poor visualisation of lower cervical fractures on conventional radiographs. Controversy exists regarding the most efficient and effective method of cervical spine evaluation in trauma. After blunt trauma, plain cervical spine radiographs are inadequate to evaluate fully the cervical spine. Occult fractures in ankylosing spondylitis may not be apparent on routine plain radiographic and even magnetic resonance imaging studies.7 Complete cervical spine CT is efficient, accurate and is commonly required whereas plain cervical spine radiographs need not be obtained.8 Even in critically injured patients with a high suspicion of cervical trauma, a cervical CT scan is the most efficient imaging tool for detecting skeletal injuries, with a sensitivity of 100%, whereas a single cross-table lateral view is insufficient with a sensitivity of only 63%.9

Severe bradyarrhythmia after high cervical spinal cord injury is an infrequent event. An autonomic imbalance in favour of the parasympathetic system is proposed. Sympathetic pathways originating in supraspinal regions are disconnected from their thoracolumbar derived peripheral system, leading to the overbalance of the parasympathetic system. In an acute injury, efferent pathways to vagal regulated areas of the brain are apparently also stimulated, resulting in increased vagal output to the heart and higher risk of asystole. In a recent study, five of 30 patients with complete cervical spinal cord injury required placement of permanent cardiac pacemakers for recurrent bradycardia or asystolic events.10 The early manifestation of neurogenic shock with bradycardia and hypotension is unusual in cervical cord injury as <20% of patients have a classical neurogenic shock upon arrival in the emergency department. It is hypothesised that heart rate and blood pressure changes in these patients develop over time so that these patients usually arrive in the emergency department before neurogenic shock has become manifest.11 The very early bradycardia in the present case may have resulted from direct spinal cord compression by bony fragments.

LEARNING POINTS

The specific combination of longstanding ankylosing spondylitis and minor trauma should serve as an alert to every clinician.

Careful neck immobilisation is strongly recommended.

Early diagnosis using cervical spine CT is essential for a favourable outcome.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Olerud C, Frost A, Bring J. Spinal fractures in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Eur Spine J 1996; 5: 51–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray GC, Persellin RH. Cervical fracture complicating ankylosing spondylitis: a report of eight cases and review of the literature. Am J Med 1981; 70: 1033–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heyde CE, Robinson Y, Kayser R, et al. [Fatal complex fracture of the cervical spine in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis after a fall from a racing bicycle]. Sportverletz Sportschaden 2007; 21: 148–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith MD, Scott JM, Murali R, et al. Minor neck trauma in chronic ankylosing spondylitis: a potentially fatal combination. J Clin Rheumatol 2007; 13: 81–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Khateeb H, Oussedik S. The management and treatment of cervical spine injuries. Hosp Med 2005; 66: 389–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thumbikat P, Hariharan RP, Ravichandran G, et al. Spinal cord injury in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a 10-year review. Spine 2007; 32: 2989–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrop JS, Sharan A, Anderson G, et al. Failure of standard imaging to detect a cervical fracture in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis. Spine 2005; 30: E417–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gale SC, Gracias VH, Reilly PM, et al. The inefficiency of plain radiography to evaluate the cervical spine after blunt trauma. J Trauma 2005; 59: 1121–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Platzer P, Jaindl M, Thalhammer G, et al. Clearing the cervical spine in critically injured patients: a comprehensive C-spine protocol to avoid unnecessary delays in diagnosis. Eur Spine J 2006; 15: 1801–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franga DL, Hawkins ML, Medeiros RS, et al. Recurrent asystole resulting from high cervical spinal cord injuries. Am Surg 2006; 72: 525–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guly HR, Bouamra O, Lecky FE. The incidence of neurogenic shock in patients with isolated spinal cord injury in the emergency department. Resuscitation 2008; 76: 57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]