Abstract

Pot1 is a single-stranded telomere-binding protein that is conserved from fission yeast to mammals. Deletion of Schizosaccharomyces pombe pot1+ causes immediate telomere loss. S. pombe Rqh1 is a homolog of the human RecQ helicase WRN, which plays essential roles in the maintenance of genomic stability. Here, we demonstrate that a pot1Δ rqh1-hd (helicase-dead) double mutant maintains telomeres that are dependent on Rad51-mediated homologous recombination. Interestingly, the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant displays a “cut” (cell untimely torn) phenotype and is sensitive to the antimicrotubule drug thiabendazole (TBZ). Moreover, the chromosome ends of the double mutant do not enter the pulsed-field electrophoresis gel. These results suggest that the entangled chromosome ends in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant inhibit chromosome segregation, signifying that Pot1 and Rqh1 are required for efficient chromosome segregation. We also found that POT1 knockdown, WRN-deficient human cells are sensitive to the antimicrotubule drug vinblastine, implying that some of the functions of S. pombe Pot1 and Rqh1 may be conserved in their respective human counterparts POT1 and WRN.

Telomeric DNA is composed of repetitive double-stranded DNA followed by a single-stranded (ss) overhang at the 3′ end of the G-rich strand. POT1 binds to the ss overhang, and it is required for both chromosomal end protection and telomere length regulation (3). Knockdown of human POT1 by RNA interference leads to apoptosis, chromosomal end-to-end fusion, activation of a DNA damage response, or changes in the overhang structure (16, 42, 47). Knockout of murine Pot1a activates a DNA damage response at the telomeres and elicits aberrant homologous recombination (HR) (15, 45). Removal of chicken POT1 also activates DNA damage responses at telomeres (8). Thus, mammalian POT1 protects telomeres from being recognized as DNA damage.

WRN and BLM are members of the RecQ helicase family (9). Defects in the WRN and BLM genes give rise to the cancer predisposition disorders Werner's syndrome (WS) and Bloom's syndrome (BS), respectively (2). WRN binds to telomeres during the S phase and is required to prevent telomere loss during DNA replication (11). Loss of murine WRN in telomerase knockout cells promotes recombination within telomeric DNA, escape from cellular senescence, and emergence of immortalized clones; the telomeres of the resultant tumors are maintained via the alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) pathway (20). POT1 binds to and stimulates WRN to unwind long telomeric forked duplexes and D loops in vitro (33). In the absence of WRN, human POT1 is required for efficient telomere C-rich strand replication in vivo (1). These data suggest a functional relationship between POT1 and WRN in the maintenance of telomeres.

Fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe Pot1 was originally identified as a distant homolog of the telomere-binding protein alpha subunit of Oxytricha nova (4, 14). Deletion of S. pombe pot1+ results in the rapid loss of telomeric DNA and chromosome circularization, making it difficult to study the function of S. pombe Pot1 in the maintenance of telomeres (4). In S. pombe, deletion of taz1+, which encodes a telomeric DNA-binding protein, causes massive telomere elongation (10). In contrast, a mutation in S. pombe rad11+, which encodes the large subunit of RPA, causes telomere shortening (32). Interestingly, a taz1 rad11 double mutant rapidly loses its telomeric DNA (19). Telomere loss in the taz1 rad11 double mutant is suppressed by the overexpression of Pot1, implying that the mechanism of telomere loss in the taz1 rad11 double mutant is related to that in the pot1 disruptant (19). Telomere loss in the taz1 rad11 double mutant is also suppressed by the deletion of rqh1+, a RecQ helicase in S. pombe (19). Rqh1 promotes telomere breakage and entanglement in the taz1 disruptant (34). However, the exact roles of Rqh1 in the maintenance of telomeres are not fully understood. Previous studies of helicase-dead Rqh1 have demonstrated the importance of the helicase activity, but a helicase-independent function has been reported as well (17, 29, 36).

In this paper, we analyze whether the deletion of rqh1+ suppresses the telomere loss observed in the pot1 disruptant. We found that the pot1Δ rqh1-hd (helicase-dead) double mutant maintains telomeres by Rad51-dependent HR. Interestingly, the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant was highly sensitive to the antimicrotubule drug thiabendazole (TBZ). Analysis of the phenotypes of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant revealed that Pot1 and Rqh1 are required for efficient chromosome segregation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain construction and growth media.

The strains used in this report are listed in Table 1. The pot1::kanMX rqh1-K547A double mutant (the pot1Δ rqh1-hd mutant) was created as follows. First, the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant expressing Pot1 from a plasmid containing the LEU2 gene (nmt1-pot1-V5; gift from Peter Baumann) was created by the transformation of rqh1-hd cells (YK002) expressing Pot1 from the plasmid nmt1-pot1-V5 using the pot1::kanMX disruption fragment, in which the complete open reading frame (ORF) is replaced by the kanMX gene (gift from Peter Baumann). The plasmid nmt1-pot1-V5 in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant was then replaced by the plasmid pPC27-pot1-3HA containing the HSV-tk and ura4+ genes as negative selection markers (a gift from Peter Baumann). The pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant that lost the plasmid pPC27-pot1-3HA was selected on yeast extract agar (YEA) plates containing 50 μM 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (FUDR) or 2 g/liter 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) at 25°C or 30°C. The pot1::kanMX rqh1-K547A rad51-d triple mutant (the pot1Δ rqh1-hd rad51Δ mutant) was created as follows. The pot1Δ rqh1-hd rad51Δ triple mutant containing the Pot1 plasmid pPC27-pot1-3HA was created by transforming the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant expressing Pot1 from pPC27-pot1-3HA with the rad51::LUE2 disruption fragment, in which the LUE2 cassette is inserted in the NheI site of the rad51 gene. The pot1Δ rqh1-hd rad51Δ triple mutant that does not have pPC27-pot1-3HA was selected on YEA plates containing 2 g/liter 5-FOA. Cells were grown in YEA medium (0.5% yeast extract, 3% glucose, and 40 μg/ml adenine) at the indicated temperature.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| S. pombe strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| JY741 | h−leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 | M. Yamamoto |

| PP74-No.4 | h+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 pot1::kanMX | P. Baumann |

| MGF809 | h−ura4-D18 rad11-GFP::kanMX | M. Ferreira |

| YK002 | h+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 rqh1-K547A | This study |

| GT000 | h+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 rqh1-K547A pot1::kanMX(pPC27-pot1+-HA) | This study |

| GT001 | h+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 rqh1-K547A pot1::kanMX rad51::LEU2 | This study |

| GT002 | h+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 rqh1-K547A pot1::kanMX | This study |

| TH001 | h+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 rqh1::hphMX pot1::kanMX(pPC27-pot1+-HA) | This study |

| KTA002 | h−ura4-D18 pot1::kanMX6 rqh1-K547A rad11-GFP::kanMX6 | This study |

| KTA003 | h+ura4-D18 ade6-M216 rqh1-K547A rad11-GFP::kanMX6 | This study |

| KTA006 | h+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 pot1::kanMX6 rqh1-K547A(pPC27-pot1+-HA) taz1-YFP::kanMX6 ssb2-Cerulean::kanMX6 | This study |

| KTA007 | h+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 pot1::kanMX6 rqh1-K547A taz1-YFP::kanMX6 ssb2-Cerulean::kanMX6 | This study |

| KTA010 | h−leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 pot1::kanMX6 rqh1-K547A rad11-mRFP::natMX6 gar2-GFP::kanMX6 | This study |

| KTA018 | h−leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 pot1::kanMX6 rqh1-K547A rad22-YFP::kanMX6 | This study |

| KTA020 | h−leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 pot1::kanMX6 rqh1-K547A rad22-YFP::kanMX6 ssb2-Cerulean::kanMX6 | This study |

| KTA022 | h+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 rqh1-K547A pot1::kanMX rad51::LEU2 rad11-mRFP::natMX6 | This study |

Measurement of telomere length.

Telomere length was measured using Southern hybridization according to a previously described procedure (10) with an AlkPhos Direct Kit module (GE Healthcare). A 450-bp synthetic telomere fragment (24) and a TAS1 or a TAS1 plus telomere fragment derived from pNSU70 (37) were used as probes. A 450-bp telomeric DNA probe was labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (Parkin Elmer) by using the Rediprime II DNA labeling system (GE Healthcare). The membrane was hybridized overnight with hybridization buffer (GE Healthcare Rapid-Hyb buffer) and the 10-ng probe at 37°C.

PFGE.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed as described by Baumann and Cech (5). For the detection of NotI-digested chromosomes, NotI-digested S. pombe chromosomal DNA was fractionated in a 1% agarose gel with a 0.5× TBE (50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM boric acid, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) buffer at 14°C using the CHEF Mapper PFGE system at 6 V/cm (200 V) and a pulse time of 60 to 120 s for 24 h. DNA was visualized by staining with ethidium bromide (1 μg/ml) for 30 min.

Microscopy.

Microscope images of living cells were obtained using an AxioCam digital camera (Zeiss) connected to an Axiovert 200 M microscope (Zeiss) with a Plan-Apo-chromat 63× 1.4-numerical-aperture (NA) objective lens. Pictures were captured and analyzed using AxioVision Rel. 4.3 software (Zeiss). A glass-bottom dish (Iwaki) was coated with 5 mg/ml lectin from Bandeiraea simplicifolia BS-I (Sigma) or 10 mg/ml concanavalin A (Wako). The time-lapse images of tagged proteins in living cells were taken at 30-s intervals at 30°C.

siRNA knockdown and drug sensitivity assay.

The simian virus 40 (SV40)-immortalized WRN-deficient human cells (W-V cells; kindly provided by Kiyoji Tanaka) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 100 μg/ml kanamycin in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. Retroviral infection was performed as previously described (35) using the pLPC/FLAG-WRN retroviral vector (kindly provided by Jan Karlseder) (11). Following infection, the cells were selected using 2 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma). To maintain the established cell lines, 0.5 μg/ml puromycin was added to the growth medium. The Stealth small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) to POT1 (no. 1, 5′-AAAGUAGACAUUCAUUUGAAAGCGG-3′, and no. 3, 5′-UAAGAAAGCUUCCAACCUUCAGAGA-3′) were purchased from Invitrogen. As a control, Stealth RNAi Negative Control LO GC (12935-200) was used. These siRNAs were transiently introduced into the cells using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Knockdown efficiency was determined using Western blot analysis as described below. Cellular sensitivity to vinblastine (48-h exposure) was determined by measuring the relative cell number at the end of the drug treatment with the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution cell proliferation assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were washed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in TNE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA) and a 1:40 volume of protease inhibitor cocktails (Sigma) on ice for 30 min. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was collected as the TNE lysate. Nuclear extracts were prepared using a CelLytic NuCLEAR extraction kit (Sigma). For the detection of POT1, the TNE lysates were immunoprecipitated using rabbit anti-POT1 antiserum D6442 (27) or normal rabbit immunoglobulin G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For the detection of WRN, the lysate was immunoprecipitated using rabbit anti-WRN ab-200 (Abcam) or mouse anti-FLAG (M2; Sigma). The immunocomplexes were subjected to Western blot analysis using affinity-purified anti-POT1 D6442 or anti-WRN (ab-200) as a primary antibody and the TrueBlot anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (eBioscience) as a secondary antibody. Signals were detected using the ECL detection system (GE Healthcare).

RESULTS

The pot1Δ rqh1-hd (helicase-dead) double mutant is viable but is sensitive to the antimicrotubule drug TBZ.

To determine whether the deletion of rqh1+ suppresses the telomere loss observed with the pot1 disruptant, we created 2 types of the pot1 rqh1 double mutant, a pot1 null rqh1 null double mutant (the pot1Δ rqh1Δ mutant) and a pot1 null rqh1-K547A double mutant (the pot1Δ rqh1-hd mutant). The Rqh1-K547A protein has no helicase activity in vitro (21). First, we created these double mutants that contained the plasmid expressing Pot1 because it was difficult to create these double mutants by tetrad analysis and conventional transformation methods. The cells that lost the plasmid were selected on plates containing 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (FUDR) (43). As previously reported, the pot1Δ rqh1Δ double mutant was not obtained at 30°C, a standard temperature for S. pombe cultivation, showing that the double mutant is synthetically lethal (43). In contrast, we were able to obtain the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant at both 25°C and 30°C (Fig. 1A and data not shown). Our results demonstrate that unlike the pot1Δ rqh1Δ double mutant, the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant is viable. This suggests that the function of Rqh1, other than its helicase activity, is required for the viability of the pot1 disruptant.

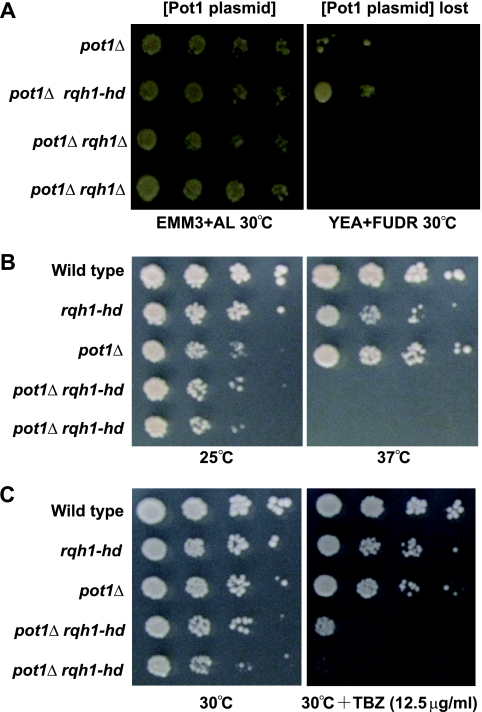

FIG. 1.

pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant is viable but is sensitive to TBZ. (A) Spotting assay of 10-fold serial dilutions of cells. The plasmid is retained on Edinburgh minimal medium (EMM) plus adenine and leucine and selected against on YEA plus FUDR at 30°C. The sensitivities to temperature (B) and TBZ (C) of wild-type, rqh1-hd, pot1Δ, and 2 independent pot1Δ rqh1-hd cells were determined using a spot test. The 10-fold dilutions of log-phase cells were spotted onto a YEA plate at the indicated temperature or a YEA plate containing 12.5 μg/ml TBZ at 30°C.

As the pot1Δ rqh1-hd cells were viable, we first tested their growth at different temperatures. Although the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant grew more slowly than wild-type and rqh1-hd cells, it grew at a rate similar to that of pot1Δ cells (Fig. 1B), which have circular chromosomes at 25°C. However, the double mutant could not grow at 37°C, indicating that it is sensitive to high temperature (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, we found that the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutants were highly sensitive to the antimicrotubule drug thiabendazole (TBZ) at 30°C (Fig. 1C), while neither the pot1Δ nor the rqh1-hd single mutant showed sensitivity to TBZ, at least at this concentration. Mutants possessing defects in chromosome segregation are sensitive to TBZ, implying that the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutation affects chromosome segregation (13, 38, 39, 46); therefore, we characterized the TBZ sensitivity mechanism of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant.

The pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant can maintain telomeres that are dependent on HR activity.

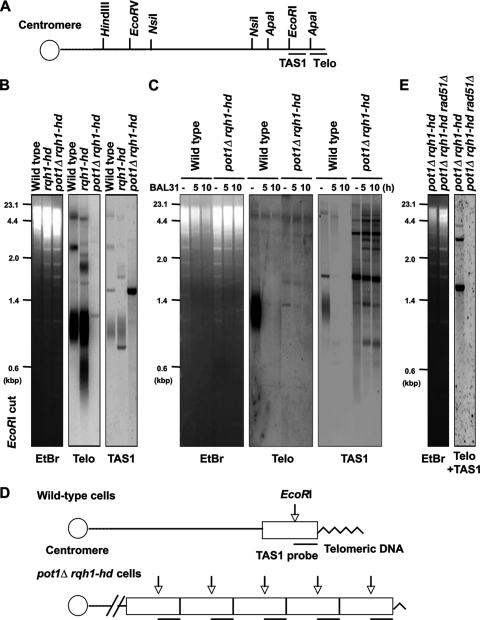

We first assessed whether the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant maintains telomeric DNA using a Southern hybridization assay. Interestingly, the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant showed hybridization signals when the genomic DNA was digested by EcoRI and the telomeric probe or when the probe containing the telomere-associated sequence (TAS1) was used (Fig. 2A and B). This is a sharp contrast to the pot1Δ cells that lose both the telomeric and TAS1 sequences completely (4). Unlike a typical telomere smear in the wild-type strain, the 1.2-kbp telomere band detected in the double mutant was very weak and sharp, implying that only a few telomeric repeats remained. This 1.2-kbp band disappeared by BAL31 nuclease digestion, suggesting that the double mutant has a telomeric sequence at the chromosome ends (Fig. 2C). The size of this 1.2-kbp band was longer than expected from simple shortening of the telomere repeat tract. A rearrangement within the terminal subtelomeric fragment could account for this, but further study will be required to understand the exact structure of the telomere ends in the double mutant. Unlike wild-type cells that have a telomeric smear, the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant had distinct and pronounced signals when the TAS1 probe was used, suggesting the amplification of the TAS1-containing subtelomere sequence (Fig. 2B and C). To test this possibility, we carried out a Southern hybridization assay with NsiI-digested genomic DNA. The sizes of the TAS1-containing terminal fragments of the wild-type cells were around 2 to 6 kbp. In contrast, the size of the TAS1-containing terminal fragment of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant was about 23 kbp, suggesting that the size of the terminal fragment is longer than 23 kbp (data not shown). Based on the size of the EcoRI-digested TAS1-containing fragment (about 1.6 kbp), we assume that the NsiI-digested terminal fragments have TAS1-containing repeats at least more than 10 repeats (Fig. 2D). This chromosome end structure may be similar to the S. cerevisiae type I survivors lacking telomerase, in which the subtelomeric sequences are amplified at telomere ends (22). The band patterns of the three independent pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutants did not significantly change during 3 restreaks, showing that the chromosome ends of the double mutants are not vigorously rearranged at 25°C (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant can maintain telomeres that are dependent on HR activity. (A) Restriction enzyme sites around the telomeric (Telo) and telomere-associated sequence (TAS1) of 1 chromosome arm cloned in the plasmid pNSU70 (37). (B) The telomere length of the wild-type, rqh1-hd, and pot1Δ rqh1-hd cells was analyzed using Southern hybridization at 25°C. Genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI, separated by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, and hybridized to a 450-bp synthetic telomere fragment as a probe, or a 700-bp DNA fragment containing the TAS1 sequence. To assess the total amount of DNA, the gel was stained with ethidium bromide (EtBr) before blotting onto the membrane. (C) BAL31 nuclease treatment of genomic DNA from wild-type and pot1Δ rqh1-hd cells. Samples were digested with 4 units of BAL31 nuclease (NEB) for 5 or 10 h. After the BAL31 treatment, genomic DNA was analyzed as described for panel B. (D) Schematic diagram of telomeric structure in wild-type and pot1Δ rqh1-hd cells. Telomeric sequences are indicated as zigzag line. TAS1-containing subtelomeric elements are indicated as a box. Vertical arrows indicate the position of EcoRI digestion. The canonical positions of TAS1 sequence are indicated by line below the box. (E) The telomere lengths of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd cells and pot1Δ rqh1-hd rad51Δ cells were analyzed using Southern hybridization at 25°C. Genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI and hybridized to a 1-kbp DNA fragment containing telomere plus TAS1 sequences.

Telomere-telomere recombination is elevated in WRN-deficient (homolog of Rqh1), telomerase knockout mouse cells (20); moreover, murine Pot1a-deficient cells exhibit aberrant HR at telomeres (45). These facts imply that telomere- telomere recombination is elevated in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant. In S. pombe, Rad51, originally named Rhp51, plays important roles in HR (28). To test the contribution of HR in the maintenance of telomeres in the double mutant, we created a pot1Δ rqh1-hd rad51Δ triple mutant. The pot1Δ rqh1-hd rad51Δ triple mutant completely lost the hybridization signal when the DNA probe contained telomeric and TAS1 sequences, showing that the chromosome ends of the double mutants are maintained by HR (Fig. 2E).

The chromosome ends of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant are entangled.

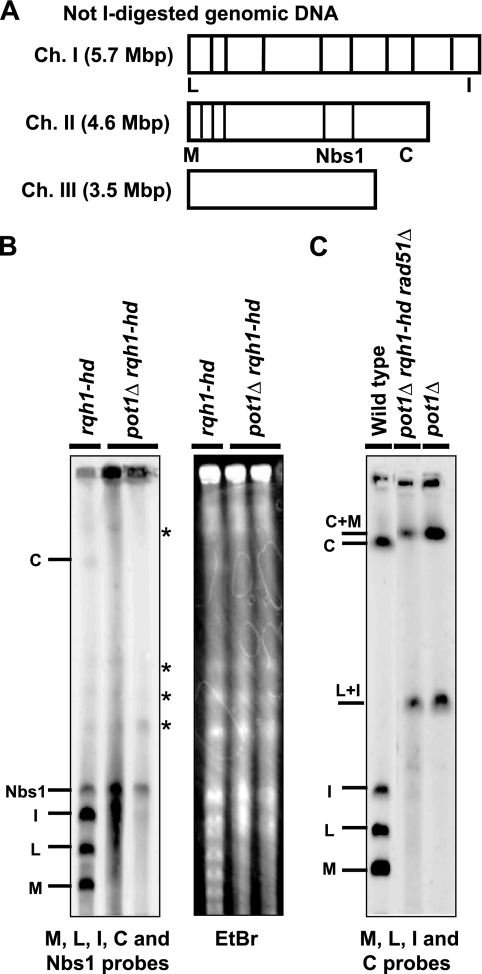

Since the chromosomes of the pot1Δ cells are circularized, the chromosomes of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutants were analyzed using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (Fig. 3A and B). The NotI-digested fragments M, L, I, and C, which are located at the ends of chromosomes I and II, were detected in the rqh1-hd single mutant. In contrast, the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant had almost no M, L, I, or C signals. The centromere proximal fragment next to the C fragment was detected when the Nbs1 probe was used as an internal control (Fig. 3A and B). Moreover, the ethidium bromide-staining pattern showed that the bulk DNA entered the gel, suggesting that only the chromosome end fragments were unable to enter the gel. DNA with branched structures, such as replicating DNA forks or recombination intermediates, cannot enter a pulsed-field gel. Our results suggest that the chromosome ends of the double mutant have branched structures, but the internal chromosome fragments do not contain these DNA structures. Similar to the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant, the chromosomes of the taz1 disruptant do not enter the pulsed-field gel at 20°C, suggesting that the telomeres in the taz1 disruptant are entangled at this temperature (23); however, unlike the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant, the taz1 disruptant is not sensitive to TBZ (23), suggesting that the type of entanglement in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant is different from that in the taz1 disruptant at 20°C. PFGE of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd rad51Δ triple mutant showed that the chromosomes of this mutant were circularized (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant chromosomes are not circularized, but the chromosome ends are entangled. (A) NotI restriction enzyme map of S. pombe chromosomes. Chromosomes I, II, and III (Ch. I, Ch. II, and Ch. III) are shown. (B) NotI-digested S. pombe chromosomal DNA from the rqh1-hd cells and 2 independent pot1Δ rqh1-hd cells that were incubated at 25°C was analyzed using PFGE. Probes specific for the NotI fragments (C, I, L, and M) and Nbs1 were used (31). The nonspecific bands detected in rqh1-hd and pot1Δ rqh1-hd cells are shown by asterisks. To assess the total amount of DNA, the gel was stained with ethidium bromide (EtBr) before blotting onto the membrane. (C) NotI-digested S. pombe chromosomal DNA of wild-type cells, pot1Δ rqh1-hd rad51Δ cells, and pot1Δ cells was analyzed using PFGE. The probes specific for the NotI fragments (C, I, L, and M) were used.

The pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant has RPA foci.

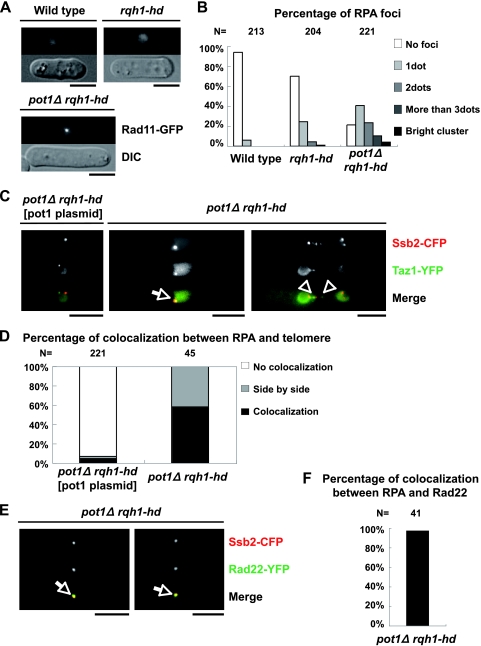

Our results suggest that the stalled replication forks and/or recombination intermediates may exist at the chromosome ends in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant. As RPA binds to the ssDNA generated during DNA replication, recombination, and damage, we monitored the localization of RPA in the double mutant by using Rad11 that was endogenously tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) (40). Most of the wild-type cells and approximately 70% of the rqh1-hd single mutants had no RPA foci (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast, approximately 80% of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutants had RPA foci, suggesting that ssDNA accumulates in the double mutant. The accumulation of ssDNA may activate the DNA damage checkpoint. Many of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant cells are elongated, and the elongation of the double mutant cells is suppressed by deletion of chk1+, suggesting that the DNA damage checkpoint is activated in the double mutant (Fig. 4A and data not shown). We also found that approximately 70% of the pot1 single mutants had no RPA foci, suggesting that circular chromosomes do not induce an excess amount of ssDNA (data not shown). Next, we tested the colocalization between RPA and the telomeres by using cells expressing endogenously tagged Taz1-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) (a telomeric marker) and Ssb2-cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) (the middle subunit of RPA) (40). The majority of the Taz1 foci in the asynchronous double mutant cells either colocalized with or localized adjacent to the Ssb2 foci, while most of the Taz1 foci in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant expressing Pot1 from a plasmid did not colocalize with the Ssb2 foci (Fig. 4C and D). This suggests that the RPA foci are produced at and/or near telomeres in the double mutant, and these foci may represent recombination intermediates, stalled replication forks, and/or ss telomeric overhangs (40). Interestingly, the Taz1 foci were adjacent to the RPA foci on the chromosomal bridge in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant (Fig. 4C, right), suggesting that the RPA foci produced near the telomeres exist during the M phase. We also tested the colocalization between RPA and Rad22 by using cells expressing endogenously tagged Rad22-YFP and Ssb2-CFP (the middle subunit of RPA) (26). Fission yeast Rad22, a Rad52 homolog, is a DNA repair protein required for HR and binds to the taz1Δ (unprotected) telomeres (7, 41). Most of the Rad22 foci in the asynchronous double mutant cells colocalized with the Ssb2 foci, suggesting that the RPA foci produced at and/or near telomeres in the double mutant represent recombination intermediates (Fig. 4E and F).

FIG. 4.

pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant has RPA foci, and the Taz1 (telomere) foci and the Rad22 (recombination) foci colocalize with the Ssb2 (RPA) foci. (A) Visualization of RPA foci in asynchronous living cells. Vegetatively growing wild-type cells, rqh1-hd cells, and pot1Δ rqh1-hd cells, in which Rad11 is endogenously tagged with GFP, were observed at 30°C. Bar = 5 μm. (B) RPA foci shown in panel A are categorized as no foci, 1 dot, 2 dots, 3 dots, and a bright cluster. The y axis indicates the percentage of cells. The total cell number examined (N) is shown at the top. (C) Merged images of fluorescence micrographs showing Ssb2-Cerulean (red) and Taz1-YFP (green) at 30°C. The middle subunit of RPA (Ssb2) and Taz1 were endogenously tagged with Cerulean (a CFP variant) and YFP in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant, respectively. pot1Δ rqh1-hd expressing Pot1 from a plasmid, which behaves like the rqh1-hd single mutant, was used as a control. The arrow and arrowheads indicate colocalization and adjacent localization, respectively. (D) The percentages of the Taz1 foci that colocalized with (colocalization) or were adjacent to (side by side) the RPA foci are presented. The total cell number examined (N) is shown at the top. (E) Merged images of fluorescence micrographs showing Ssb2-Cerulean (red) and Rad22-YFP (green) at 30°C. The middle subunit of RPA (Ssb2) and Rad22 were endogenously tagged with Cerulean (a CFP variant) and YFP in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant, respectively. (F) The percentage of the Rad22 foci that colocalized with the RPA foci is presented. The total cell number examined (N) is shown at the top.

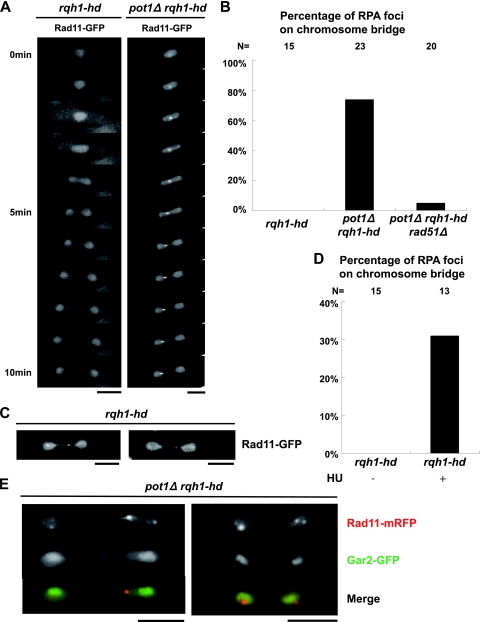

The pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant has RPA foci during the M phase.

We monitored the RPA foci in the double mutant during the M phase because our results suggested that entangled telomeres caused the M-phase defect. While the rqh1-hd single mutant did not have RPA foci during the M phase, the RPA foci appeared on chromosomal bridges during anaphase in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant at a high frequency (Fig. 5A and B), suggesting that ssDNA exists during anaphase in the double mutant. Similar to the case of the RPA foci, the Rad22 foci appeared on chromosomal bridges during anaphase in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant at a high frequency, but not in the rqh1-hd single mutant (data not shown), suggesting that the recombination intermediates exist during anaphase in the double mutant. We found that the pot1Δ rqh1-hd rad51Δ triple mutant, which has circular chromosomes, has almost no RPA foci on the chromosome bridge during anaphase (Fig. 5B), suggesting that the foci detected in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant are produced at the chromosome ends. Importantly, the RPA foci detected in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant existed before the cells entered anaphase, showing that the RPA foci are not produced during anaphase. This ruled out the possibility that the RPA foci are produced by a breakage-fusion-bridge cycle. Our results suggest that the DNA damage checkpoint activated in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant resulted in cell cycle arrest at the G2/M boundary. However, a subset of cells eventually breaks through the arrest to enter mitosis.

FIG. 5.

The pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant and rqh1-hd single mutant released from S-phase arrest have RPA foci during the M phase. (A) Visualization of RPA foci during the M phase in asynchronous living cells. Rad11-GFP-expressing living rqh1-hd cells and pot1Δ rqh1-hd cells were observed in a series of time-lapse images taken at 1-min intervals at 30°C. Bar = 5 μm. Time zero represents the time just before cells enter anaphase. (B) Percentages of cells in which the RPA foci (shown in panel A) appeared on the chromosome bridges are shown. The data from the analysis of the Rad11-mRFP-expressing living pot1Δ rqh1-hd rad51Δ were also added. The total number of M phase cells that were observed in this experiment (N) is shown at the top. (C) Visualization of RPA foci during the M phase in rqh1-hd cells released from S-phase arrest. Rad11-GFP-expressing living rqh1-hd cells released from S-phase arrest were observed at 30°C. We added 10 mM HU to an asynchronous culture of Rad11-GFP-expressing rqh1-hd cells in YEA medium. After 4 h in HU, the cells were washed and transferred to YEA medium without HU and cultured for a further 2 h. The resulting cells were observed. Two different rqh1-hd cells are shown. Bar = 5 μm. (D) Percentages of rqh1-hd cells in which the RPA foci, shown in panel C, appeared on chromosome bridges are shown. The total number of M-phase cells that were observed in this experiment (N) is shown at the top. (E) RPA foci in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant do not colocalize with Gar2 (rDNA). Merged images of fluorescence micrographs showing Rad11-mRFP (red) and Gar2-GFP (green) in the two different pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant cells during the M phase at 30°C.

The rqh1 mutant does not fully activate known checkpoints and shows a “cut” (cell untimely torn) phenotype in which chromosomes are bisected by the septum when the cells are released from hydroxyurea (HU) arrest (36). Holliday junctions (HJ) or other recombination intermediates that exist during the M phase are thought to be the cause of the cut phenotype (12). We were able to detect RPA foci during the M phase in the rqh1-hd single mutant after releasing the cells from HU arrest (Fig. 5C and D), suggesting that the RPA foci detected during the M phase represent recombination intermediates. These foci are similar to those detected in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant (Fig. 5A and B), implying that the accumulation of ssDNA in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant during the M phase represents recombination intermediates.

As the rqh1 single mutant has a defect in nucleolar segregation (44), RPA foci in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant during the M phase may also be produced at ribosomal DNA (rDNA). To test this possibility, we analyzed the colocalization between rDNA and RPA during the M phase by using cells expressing endogenously tagged Gar2-GFP, a marker of rDNA, and Rad11-monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP) (34a). We observed 18 cells of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant during the M phase. We detected only one example of the side-by-side localization between Rad11-mRFP and Gar2-GFP during the M phase, but we could not detect colocalization between Rad11-mRFP and Gar2-GFP during the M phase (Fig. 5E), indicating that the RPA foci detected in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant during the M phase are not produced inside the rDNA.

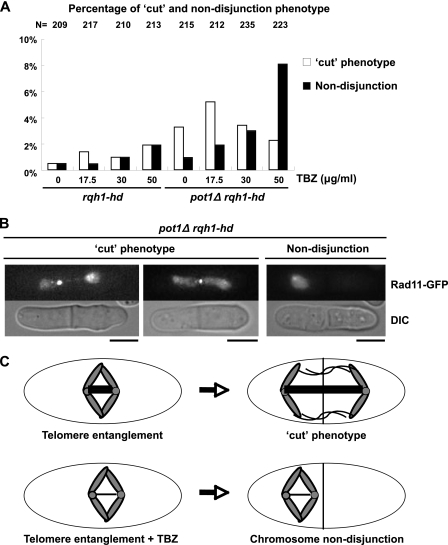

pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant has a chromosome segregation defect.

The ssDNA observed during the M phase in the double mutant, possibly recombination intermediates, may cause a chromosome segregation defect because these structures will physically link sister chromatids together. Indeed, the frequency of the cut phenotype of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant was significantly higher than that of the rqh1-hd single mutant in the absence of TBZ (Fig. 6A). We also studied the chromosome segregation defect in the presence of TBZ because the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant is sensitive to TBZ. In the presence of a low concentration of TBZ (17.5 μg/ml), the frequency of the cut phenotype of the double mutant was significantly higher than that of the rqh1-hd single mutant (Fig. 6A and B). At a high concentration of TBZ (50 μg/ml), the frequency of chromosome nondisjunction increased in the double mutant, but not in the rqh1-hd single mutant. These results suggest that the fully or partially functional mitotic spindle can segregate chromosomes even though the chromosome ends are entangled, causing the cut phenotype. At a high concentration of TBZ (50 μg/ml), the destabilized mitotic spindle cannot segregate the entangled chromosomes, resulting in chromosome nondisjunction (Fig. 6C). On the basis of these data, we conclude that entanglement of the chromosome ends in the double mutant is the cause of its sensitivity to TBZ. The trt1 single mutant was not sensitive to TBZ when cells were grown in liquid culture both in early generations that have telomeric DNA and in late generations that have linear chromosomes in a recombination-dependent manner, demonstrating that the telomere recombination itself is not the cause of the TBZ sensitivity (M. Ueno, unpublished observations). However, a third type of trt1 survivor called HAATI has been reported (18). This survivor shares some phenotypes with the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant, including HR-dependent maintenance of the chromosome ends and stacking chromosomes at wells of the pulsed-field gel. Therefore, this survivor may have chromosome segregation defects similar to those of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant.

FIG. 6.

pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant has a defect in chromosome segregation. (A) Percentage of defects in chromosome segregation in asynchronous living cells. The indicated concentrations of TBZ were added to an asynchronous culture of Rad11-GFP-expressing rqh1-hd cells and pot1Δ rqh1-hd cells in YEA medium for 4 h. The resulting cells were observed at 30°C. As RPA localizes to the entire nucleus, chromosome segregation defects were monitored by the localization of RPA. The total number of asynchronous living cells that were observed in this experiment (N) is shown at the top. The y axis indicates the percentage of cells that display the cut or nondisjunction phenotype. (B) An example of the cut phenotype (in the presence of 17.5 μg/ml TBZ [left] and in the presence of 50 μg/ml TBZ [middle] and nondisjunction [in the presence of 50 μg/ml TBZ (right panel)]) in pot1Δ rqh1-hd cells are shown. (C) Model for chromosome segregation defects in pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant. One pair of sister chromatids in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant, in which the telomeres are entangled during the M phase, is shown. The kinetochore/centromere is shown by a small circle. The mitotic spindle between the kinetochore/centromere is shown by a thick line. The mitotic spindle is destabilized in the presence of TBZ (shown by a thin line).

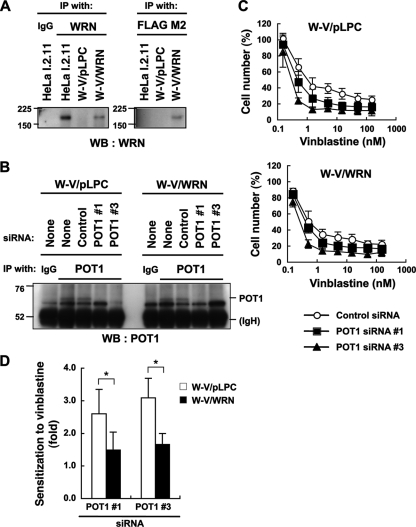

Simultaneous inactivation of human POT1 and WRN enhances cellular sensitivity to the antimicrotubule drug vinblastine.

Many of the telomere-binding proteins in S. pombe are conserved in humans (26). This prompted us to assess whether human Pot1 and WRN (homolog of Rqh1) are required for viability in the presence of the antimicrotubule drug vinblastine, which inhibits microtubule polymerization. In order to address this issue, we first reconstituted wild-type WRN in SV40-transformed, WRN-deficient W-V cells (Fig. 7A). The resulting infectant (W-V/WRN) and the control cell line (W-V/pLPC) were further transfected with siRNAs to deplete the POT1 protein (Fig. 7B). Under these conditions, cellular sensitivity to vinblastine was monitored. As shown in Fig. 7C (bottom), POT1 knockdown enhanced the cytotoxicity of vinblastine to some extent in the W-V/WRN cells. These data indicate that, in human cells, depletion of POT1 alone can enhance the deleterious effect of vinblastine. Importantly, this effect of POT1 depletion on the sensitivity to the drug was more evident under WRN-deficient conditions (Fig. 7C, top). In fact, sensitization to vinblastine, which was defined as a ratio of 50% growth inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of control siRNA-treated cells to those of POT1 knockdown cells, was higher in W-V/pLPC cells than in W-V/WRN cells (Fig. 7D). These observations indicate that deficiencies in POT1 and WRN increase the sensitivity of cultured human cells to the antimicrotubule drug vinblastine.

FIG. 7.

POT1 and WRN deficiencies render human cultured cells sensitive to vinblastine. (A) Establishment of the cell lines. WRN-deficient W-V cells were infected with the retrovirus for FLAG-tagged WRN (W-V/WRN). W-V/pLPC is a mock infectant used as the control. The TNE lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP), followed by Western blot analysis (WB). HeLa I.2.11 cells were used as a control for the detection of endogenous WRN. IgG, normal immunoglobulin G. Values indicate the protein size markers (in thousands). (B) POT1 depletion using siRNA. The cells were transfected with the indicated siRNA. After a 48-h incubation, the TNE lysates were subjected to IP, followed by Western blot analysis. IgH, immunoglobulin heavy chain. (C) Effects of POT1 and WRN deficiencies on the sensitivity to vinblastine, an inhibitor of microtubule polymerization. The cells were transfected with the indicated siRNA for 24 h and then incubated with various concentrations of vinblastine for 48 h. Cell number (%) refers to the cell counts normalized to those in the absence of vinblastine. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of 3 or 4 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. (D) Reconstitution of WRN counteracts the POT1 knockdown-induced sensitization to vinblastine in W-V cells. Sensitization to vinblastine (ratio of IC50 values of control siRNA-treated cells to those of POT1 knockdown cells) was determined from the data shown in panel C. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of 3 or 4 independent experiments. Asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Telomeres are maintained by HR in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant.

The S. pombe pot1 disruptant suffers an immediate loss of telomeric DNA followed by fusion of its chromosome ends (4). In this study, we found that the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant could maintain its telomeres. As the Pot1 complex is required for the recruitment of telomerase to the telomere (26, 40), it is likely that telomerase cannot function in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant. Indeed, telomeres in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant were maintained by HR. Rqh1 inhibits inappropriate recombination (36); therefore, the hyperrecombination phenotype of the rqh1-hd mutant is likely to increase the probability of HR at the chromosome ends when pot1+ is deleted. This could be the reason why the double mutant can maintain its telomeres. The S. cerevisiae RecQ helicase Sgs1 is involved in the degradation of the 5′ strand at both double-strand breaks (DSB) and telomeres (6, 25, 48). These facts imply that Rqh1 may be involved in the degradation of telomeres in pot1Δ cells. Unlike pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutants, the pot1Δ rqh1 double mutant is synthetically lethal (43), suggesting that the helicase-independent function of Rqh1 is important for viability in the absence of Pot1. As Rqh1 binds to several proteins, such as Top3 and RPA (19, 21), helicase-dead Rqh1 may have a function with these or other proteins to maintain the viability of the pot1Δ cells. Further investigation is required to understand the reason for the synthetic lethality.

The pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant is sensitive to TBZ and has defects in chromosome segregation.

The progression of anaphase is delayed in cells lacking Rqh1, and the cells have lagging chromosomal DNA, which is apparent at the rDNA loci (44). However, the rqh1 mutant is not sensitive to TBZ at the concentration that we tested, suggesting that the segregation defect of the rDNA loci in the rqh1 mutant is not catastrophic to the cells. Interestingly, the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant was highly sensitive to TBZ. PFGE analysis of the NotI-digested genomic DNA suggests that the chromosome ends of the double mutant are entangled. The pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant displayed RPA foci, a marker of DNA recombination, damage, or stalled replication forks, at a high frequency in asynchronous cells (mainly the G2 phase) and in M-phase cells, and many Taz1 foci and Rad22 foci colocalized with the RPA foci, suggesting that the recombination intermediates are produced at and/or near the telomeres. The RPA foci did not colocalize with the rDNA marker Gar2, suggesting that the defects in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant are not due to problems with rDNA. The recombination intermediates that were produced following the release from HU arrest in the rqh1 mutant inhibit proper chromosome segregation, resulting in the cut phenotype. We detected RPA foci during the M phase in the rqh1-hd single mutant after the cells were released from HU arrest, suggesting that these RPA foci represent recombination intermediates. The pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant also displayed the cut phenotype; moreover, RPA foci were detected during the M phase in the double mutant. These facts imply that DNA entanglement produced at the chromosome ends in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant may have a similar structure to those produced in the rqh1-hd single mutant following release from HU arrest, which is suggested to be an HJ. However, as human Pot1 and WRN are required for efficient DNA replication (1, 11), we do not rule out the possibility that RPA foci in the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant represent stalled replication forks at and/or near the telomeres. However, the stalled replication forks would cause DNA breaks, which would become the substrates for HR.

As the pot1Δ rqh1-hd rad51Δ triple mutant has circular chromosomes, it is expected that the triple mutant is not sensitive to TBZ because its chromosomes are not entangled. However, the rad51 single mutant is sensitive to TBZ (30), making it difficult to compare the phenotypes of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant and the pot1Δ rqh1-hd rad51Δ triple mutant. Indeed, the pot1Δ rqh1-hd rad51Δ triple mutant was sensitive to TBZ, but the TBZ sensitivity of the triple mutant was slightly weaker than that of the double mutant, suggesting that the entangled chromosomal ends in the double mutant affected the TBZ sensitivity (data not shown). The ccq1 single mutant shares some phenotypes with the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant, including HR-dependent telomere maintenance, RPA foci, and the cut phenotype (40). However, unlike those of the pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant, the chromosome end fragments of the ccq1 single mutant and ccq1 rqh1 double mutant can enter the pulsed-field gel, suggesting that the chromosome ends of the ccq1 single mutant and ccq1 rqh1 double mutant are not severely entangled.

Clinical implications of hypersensitivity to antimicrotubule drugs.

We found that the knockdown of POT1 in SV40-immortalized WRN-deficient cells rendered the cells more sensitive to vinblastine. These observations are similar to those of the S. pombe pot1Δ rqh1-hd double mutant, implying that the functions of S. pombe Pot1 and Rqh1 may be conserved in their respective human counterparts, POT1 and WRN. However, our telomere fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of metaphase spreads revealed that POT1 depletion in W-V cells did not induce end-to-end fusions or entanglement-like features of chromosomes (H. Seimiya, unpublished observations). These observations suggest that either POT1 depletion in WRN-deficient cells is not enough to induce the same phenotype as that observed in S. pombe or that the underlying mechanisms for the higher sensitivities to TBZ in S. pombe and vinblastine in humans may not completely overlap each other. Nevertheless, our finding that depletion of POT1 alone in human cells can enhance their sensitivity to vinblastine suggests that human POT1 is involved in chromosome segregation.

Since antimicrotubule compounds are commonly used as anticancer drugs in the clinical setting, our results suggest a novel approach for sensitizing cancer cells to antimicrotubule drugs by inactivating either POT1 or both POT1 and WRN. Indeed, we observed that a human cancer cell line expressing low levels of POT1 and WRN proteins exhibits a relatively higher sensitivity to antimicrotubule drugs (Y. Muramatsu, Y. Yamori, and H. Seimiya, unpublished observations).

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Baumann, J. Murray, K. Tomita, M. Ferreira, J. Cooper, J. Karlseder, K. Tanaka, T. Ohno, T. Toda, R. Tesin, T. Sakuno, Y. Watanabe, Shao-Win Wang, and the National Bioresource Project Japan for providing the plasmids and strains. We thank M. Mizunuma and K. Mizuta for their help in microscopy.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan to Masaru Ueno. Tatsuya Kibe is a Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnoult, N., C. Saintome, I. Ourliac-Garnier, J. F. Riou, and A. Londono-Vallejo. 2009. Human POT1 is required for efficient telomere C-rich strand replication in the absence of WRN. Genes Dev. 23:2915-2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachrati, C. Z., and I. D. Hickson. 2003. RecQ helicases: suppressors of tumorigenesis and premature aging. Biochem. J. 374:577-606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumann, P. 2006. Are mouse telomeres going to pot? Cell 126:33-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumann, P., and T. R. Cech. 2001. Pot1, the putative telomere end-binding protein in fission yeast and humans. Science 292:1171-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumann, P., and T. R. Cech. 2000. Protection of telomeres by the Ku protein in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:3265-3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonetti, D., M. Martina, M. Clerici, G. Lucchini, and M. P. Longhese. 2009. Multiple pathways regulate 3′ overhang generation at S. cerevisiae telomeres. Mol. Cell 35:70-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carneiro, T., et al. 2010. Telomeres avoid end detection by severing the checkpoint signal transduction pathway. Nature 467:228-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Churikov, D., C. Wei, and C. M. Price. 2006. Vertebrate POT1 restricts G-overhang length and prevents activation of a telomeric DNA damage checkpoint but is dispensable for overhang protection. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:6971-6982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cobb, J. A., and L. Bjergbaek. 2006. RecQ helicases: lessons from model organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:4106-4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper, J. P., E. R. Nimmo, R. C. Allshire, and T. R. Cech. 1997. Regulation of telomere length and function by a Myb-domain protein in fission yeast. Nature 385:744-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crabbe, L., R. E. Verdun, C. I. Haggblom, and J. Karlseder. 2004. Defective telomere lagging strand synthesis in cells lacking WRN helicase activity. Science 306:1951-1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doe, C. L., J. Dixon, F. Osman, and M. C. Whitby. 2000. Partial suppression of the fission yeast rqh1− phenotype by expression of a bacterial Holliday junction resolvase. EMBO J. 19:2751-2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ekwall, K., et al. 1996. Mutations in the fission yeast silencing factors clr4+ and rik1+ disrupt the localisation of the chromo domain protein Swi6p and impair centromere function. J. Cell Sci. 109(11):2637-2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray, J. T., D. W. Celander, C. M. Price, and T. R. Cech. 1991. Cloning and expression of genes for the Oxytricha telomere-binding protein: specific subunit interactions in the telomeric complex. Cell 67:807-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hockemeyer, D., J. P. Daniels, H. Takai, and T. de Lange. 2006. Recent expansion of the telomeric complex in rodents: two distinct POT1 proteins protect mouse telomeres. Cell 126:63-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hockemeyer, D., A. J. Sfeir, J. W. Shay, W. E. Wright, and T. de Lange. 2005. POT1 protects telomeres from a transient DNA damage response and determines how human chromosomes end. EMBO J. 24:2667-2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hope, J. C., S. M. Mense, M. Jalakas, J. Mitsumoto, and G. A. Freyer. 2006. Rqh1 blocks recombination between sister chromatids during double strand break repair, independent of its helicase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:5875-5880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain, D., A. K. Hebden, T. M. Nakamura, K. M. Miller, and J. P. Cooper. 2010. HAATI survivors replace canonical telomeres with blocks of generic heterochromatin. Nature 467:223-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kibe, T., Y. Ono, K. Sato, and M. Ueno. 2007. Fission yeast Taz1 and RPA are synergistically required to prevent rapid telomere loss. Mol. Biol. Cell 18:2378-2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laud, P. R., et al. 2005. Elevated telomere-telomere recombination in WRN-deficient, telomere dysfunctional cells promotes escape from senescence and engagement of the ALT pathway. Genes Dev. 19:2560-2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laursen, L. V., E. Ampatzidou, A. H. Andersen, and J. M. Murray. 2003. Role for the fission yeast RecQ helicase in DNA repair in G2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:3692-3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundblad, V., and E. H. Blackburn. 1993. An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est1− senescence. Cell 73:347-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller, K. M., and J. P. Cooper. 2003. The telomere protein Taz1 is required to prevent and repair genomic DNA breaks. Mol. Cell 11:303-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller, K. M., O. Rog, and J. P. Cooper. 2006. Semi-conservative DNA replication through telomeres requires Taz1. Nature 440:824-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mimitou, E. P., and L. S. Symington. 2008. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature 455:770-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyoshi, T., J. Kanoh, M. Saito, and F. Ishikawa. 2008. Fission yeast Pot1-Tpp1 protects telomeres and regulates telomere length. Science 320:1341-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muramatsu, Y., H. Tahara, T. Ono, T. Tsuruo, and H. Seimiya. 2008. Telomere elongation by a mutant tankyrase 1 without TRF1 poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation. Exp. Cell Res. 314:1115-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muris, D. F., et al. 1993. Cloning the RAD51 homologue of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:4586-4591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray, J. M., H. D. Lindsay, C. A. Munday, and A. M. Carr. 1997. Role of Schizosaccharomyces pombe RecQ homolog, recombination, and checkpoint genes in UV damage tolerance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6868-6875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakamura, K., et al. 2008. Rad51 suppresses gross chromosomal rearrangement at centromere in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO J. 27:3036-3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura, T. M., J. P. Cooper, and T. R. Cech. 1998. Two modes of survival of fission yeast without telomerase. Science 282:493-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ono, Y., et al. 2003. A novel allele of fission yeast rad11 that causes defects in DNA repair and telomere length regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:7141-7149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Opresko, P. L., et al. 2005. POT1 stimulates RecQ helicases WRN and BLM to unwind telomeric DNA substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 280:32069-32080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rog, O., K. M. Miller, M. G. Ferreira, and J. P. Cooper. 2009. Sumoylation of RecQ helicase controls the fate of dysfunctional telomeres. Mol. Cell 33:559-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34a.Sato, M., S. Dhut, and T. Toda. 2005. New drug-resistant cassettes for gene disruption and epitope tagging in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 22:583-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seimiya, H., Y. Muramatsu, S. Smith, and T. Tsuruo. 2004. Functional subdomain in the ankyrin domain of tankyrase 1 required for poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of TRF1 and telomere elongation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:1944-1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart, E., C. R. Chapman, F. Al-Khodairy, A. M. Carr, and T. Enoch. 1997. rqh1+, a fission yeast gene related to the Bloom's and Werner's syndrome genes, is required for reversible S phase arrest. EMBO J. 16:2682-2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sugawara, N. 1988. DNA sequences at the telomeres of the fission yeast S. pombe. Ph.D. thesis. Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

- 38.Tanaka, K., et al. 1999. Characterization of a fission yeast SUMO-1 homologue, pmt3p, required for multiple nuclear events, including the control of telomere length and chromosome segregation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:8660-8672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tatebayashi, K., J. Kato, and H. Ikeda. 1998. Isolation of a Schizosaccharomyces pombe rad21ts mutant that is aberrant in chromosome segregation, microtubule function, DNA repair and sensitive to hydroxyurea: possible involvement of Rad21 in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Genetics 148: 49-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomita, K., and J. P. Cooper. 2008. Fission yeast Ccq1 is telomerase recruiter and local checkpoint controller. Genes Dev. 22:3461-3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van den Bosch, M., et al. 2001. Characterization of RAD52 homologs in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mutat. Res. 461:311-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veldman, T., K. T. Etheridge, and C. M. Counter. 2004. Loss of hPot1 function leads to telomere instability and a cut-like phenotype. Curr. Biol. 14:2264-2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, X., and P. Baumann. 2008. Chromosome fusions following telomere loss are mediated by single-strand annealing. Mol. Cell 31:463-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Win, T. Z., H. W. Mankouri, I. D. Hickson, and S. W. Wang. 2005. A role for the fission yeast Rqh1 helicase in chromosome segregation. J. Cell Sci. 118:5777-5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu, L., et al. 2006. Pot1 deficiency initiates DNA damage checkpoint activation and aberrant homologous recombination at telomeres. Cell 126: 49-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xhemalce, B., J. S. Seeler, G. Thon, A. Dejean, and B. Arcangioli. 2004. Role of the fission yeast SUMO E3 ligase Pli1p in centromere and telomere maintenance. EMBO J. 23:3844-3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang, Q., Y. L. Zheng, and C. C. Harris. 2005. POT1 and TRF2 cooperate to maintain telomeric integrity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:1070-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu, Z., W. H. Chung, E. Y. Shim, S. E. Lee, and G. Ira. 2008. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell 134:981-994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]