Abstract

The periplasmic protein ApbE was identified through the analysis of several mutants defective in thiamine biosynthesis and was implicated as having a role in iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis or repair. While mutations in apbE cause decreased activity of several iron-sulfur enzymes in vivo, the specific role of ApbE remains unknown. Members of the AbpE family include NosX and RnfF, which have been implicated in oxidation-reduction associated with nitrous oxide and nitrogen metabolism, respectively. In this work, we show that ApbE binds one FAD molecule per monomeric unit. The structure of ApbE in the presence of bound FAD reveals a new FAD-binding motif. Protein variants that are nonfunctional in vivo were generated by random and targeted mutagenesis. Each variant was substituted in the environment of the FAD and analyzed for FAD binding after reconstitution. The variant that altered a key tyrosine residue involved in FAD binding prevented reconstitution of the protein.

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 (S. enterica) strains with lesions in apbE were initially isolated as conditional thiamine auxotrophs (5). Additional studies found that apbE mutants displayed phenotypic behaviors similar to those of strains lacking isc (iron-sulfur [Fe-S] cluster biosynthesis) operon functions (1), suggesting a role for this protein in Fe-S cluster metabolism (38). The product of the apbE gene was found to be a 36-kDa membrane-associated lipoprotein (5). Further analysis showed that ApbE was anchored to the periplasmic side of the inner membrane and that a periplasmic location, but not a lipid anchor, was necessary for ApbE function in vivo (6).

ApbE shares homology to the C-terminal portion of RnfF (Rhodobacter capsulatus), a protein thought to be involved in electron transfer. Rnf proteins are membrane associated and are thought to transfer reducing equivalents to cytoplasmic proteins, such as soxR and the dinitrogenase reductase NifH (27, 36). Experiments with Azotobacter vinelandii showed that an rnf mutation causes defects in Fe-S cluster metabolism (36). Recently, it was shown that RnfG and RnfD are flavoproteins, consistent with their role in oxidation-reduction reactions (2). ApbE also shows similarity to NosX, a protein required for dissimilatory nitrous oxide reduction (11) and involved in biofilm formation in Streptococcus gordonii (30). NosX has a physiological role in sustaining the reaction cycle of copper-containing nitrous oxide reductase, possibly through electron donation to the copper center (40).

Proteins involved in electron transfer reactions typically function via organic or inorganic cofactors that cycle between different oxidation states. For the nucleotide-dependent electron transfer proteins and enzymes, nicotinamide (for NAD+ or NADP+) and/or flavin (for flavin adenine dinucleotide [FAD] and flavin mononucleotide) serves to transfer electrons in the form of hydrides or hydrogen atoms. Flavins are unique redox cofactors because of their ability to accept or donate two electrons in one electron succession, allowing them to participate in one-electron transfer reactions. Because of this versatility, flavins are used by a number of proteins (flavoproteins) that have diverse cellular functions, including catalysis, oxygen activation, electron transfer, and redox and light sensing (22, 32).

In bacteria, the majority of FAD-containing proteins have been found in the cytoplasm. A number of membrane-spanning proteins, such as succinate dehydrogenase and cytoplasmic membrane-associated proteins, such as the tricarballylate dehydrogenase, TcuA, function to transfer reducing equivalents into the electron transport chain (29). Recent studies have identified proteins in the periplasmic space that contain FAD. An 8-methylmenaquinol:fumarate reductase (MFR) enzyme that was purified from the periplasmic space of Wolinella succinogenes contained covalently bound FAD (25). A methacrylate reductase (MCR) enzyme was purified from the periplasm of Geobacter sulfurreducens AM-1 and contained a noncovalently bound FAD (33). The MFR and MCR enzymes are thought to allow organisms to use fumarate or methacrylate as terminal electron acceptors and are located in the periplasm to avoid membrane translocation before substrate reduction. Finally, the YagTSRQ complex of Escherichia coli catalytically reduced aldehydes and YagS had a covalently bound FAD (35).

The current study was initiated to correlate the biophysical properties of the ApbE protein with its in vivo function and thus begin to address the hypothesized physiological role of this protein. Experiments described here found that ApbE is a flavoprotein, consistent with its proposed role in electron transfer, and further, its structure revealed a new FAD-binding motif.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and chemicals.

All strains used in this study are derived from S. enterica LT2 and are described in Table 1. No-carbon E salts (NCE) medium of Berkowitz et al. (7) was made with Milli-Q filtered water (MQH2O) and supplemented with 11 mM glucose, 0.4 mM adenine, 1 mM MgSO4, and trace minerals (3, 14, 39). Difco nutrient broth (NB; 8 g/liter) with NaCl (5 g/liter) or lysogenic broth (8, 9) was used as rich medium. Difco BiTek agar was added (15 g/liter) for solid medium. When it was present in the medium, thiamine was added to a concentration of 100 nM. When needed, antibiotics were added to the following concentrations in rich medium: chloramphenicol, 20 μg/ml, and ampicillin, 50 μg/ml. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and were of the highest purity available. Buffers used were as follows: buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6), buffer B (50 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 1 M NaCl), buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl), and elution buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 250 mM imidazole).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmidsa

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or insert (variant), vectorc | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. entericab | ||

| DM9722 | apbE42::Tn10d(Tc) yggX::Gm | Lab collection |

| DM12860 | yojI8065::MudJ zxx-8077::Tn10d(Tc) apbE171d | |

| DM12861 | yojI8065::MudJ zxx-8077::Tn10d(Tc) apbE172 | |

| DM12862 | yojI8065::MudJ zxx-8077::Tn10d(Tc) apbE180 | |

| DM12863 | yojI8065::MudJ zxx-8077::Tn10d(Tc) apbE181 | |

| DM16864 | yojI8065::MudJ zxx-8077::Tn10d(Tc) apbE182 | |

| DM16865 | yojI8065::MudJ zxx-8077::Tn10d(Tc) apbE183 | |

| DM12866 | yojI8065::MudJ zxx-8077::Tn10d(Tc) apbE184 | |

| DM12867 | yojI8065::MudJ zxx-8077::Tn10d(Tc) apbE185 | |

| DM12868 | yojI8065::MudJ zxx-8077::Tn10d(Tc) apbE186 | |

| DM12869 | yojI8065::MudJ zxx-8077::Tn10d(Tc) apbE187 | |

| DM12870 | yojI8065::MudJ zxx-8077::Tn10d(Tc) apbE188 | |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α/F′ | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) phoA supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 λ− | Invitrogen |

| BL21(AI*) | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm araB::T7RNAP-tetA | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSU19 | None, pSU19 | 4 |

| pET20b | None, pET20b | Invitrogen |

| pApbE1 | ApbE, pSU19 | 5 |

| pApbE10 | rApbE,e pET20b | 6 |

| pJMB129 | apbE209 (ApbEY78A), pSU19 | |

| pJMB130 | apbE209 (rApbEY78A), pET20b | |

| pJMB131 | apbE181 (rApbES76F), pET20b | |

| pJMB132 | apbE183 (rApbEG255S), pET20b | |

| pJMB133 | apbE186 (rApbET184M), pET20b |

Unless noted otherwise, all strains and plasmids were created for this study.

All S. enterica strains used in this study were constructed in the LT2 background.

Abbreviations: Tc, tetracycline; Gm, gentamicin.

Strains DM12860 to DM12870 carry an uncharacterized null allele of yggX that facilitates the detection of the thiamine requirement generated by a lack of apbE (19).

rApbE variants do not have the lipoprotein signal and accumulate in the cytoplasm.

Genetic methods. (i) Mutant isolation.

A P22 lysate was generated on strain DM3417 (yojI::MudJ), which carries an insertion ∼80% linked to the apbE locus. The lysate was mutagenized with hydroxylamine as described previously (24). The mutagenized lysate was used to transduce a wild-type (WT) recipient to Kanr, and colonies were screened for thiamine auxotrophs. The apbE mutants were reconstructed by transducing the relevant alleles into new strains.

(ii) Phenotypic analysis.

Nutritional requirements were assessed on solid medium and by quantification of growth in liquid medium using 200-μl cultures in a 96-well plate. Protocols for each have been described previously (10). The starting A650 was routinely between 0.03 and 0.08, with the final A650 being between 0.5 and 1.1. Each culture had at least three replicates. Growth on solid medium was scored after replica printing to relevant medium and incubation at 37°C for 48 to 60 h.

Molecular biology.

Restriction enzymes were purchased from Promega, and Herculase DNA polymerase was purchased from Stratagene. Plasmids were introduced into strains by electroporation. Plasmids pApbE1 and pApbE10 were used as template DNA for site-directed mutagenesis (to create AbpEY78A), generating pJMB129 and pJMB130, respectively. Plasmid pApbE10 encodes WT ApbE with a C-terminal polyhistidine tag. Primers used to introduce apbE209 were ApbE Y78A forward (GTTGCTTTCTACCGCTAAAAATGACTCCGCGTT) and ApbE Y78A reverse (ACGCATCAACGCGGAGTCATTTTTAGCGGTAGA). Plasmids pJMB131, pJMB132, and pJMB133 were created with pAPBE10 as the template using (i) primers S76F for (GTTGCTTTTTACCTATAAAAA) and S76F rev (TTATAGGTAAAAAGCAACCAA), (ii) primers G255S for (CAGCACCTCCAGCAGCTACC) and G255S rev (GGTAGCTGCTGGAGGTGCTG), and (iii) primers T184M for (CTCTCCATGGTCGGGGAGGG) and T184M rev (CCCCGACCATGGAGAGATCA), respectively. In each case, the PCR products were digested with DpnI for 1 h and transformed into E. coli DH5α. Plasmids were isolated from individual colonies and sequenced to confirm the presence of the relevant mutation. All DNA sequences were obtained by the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center.

Protein expression.

Escherichia coli strain BL21(AI*) containing the constructs expressing ApbE variants that lacked the lipoprotein signal peptide (abbreviated rApbE) were grown in LB medium at 37°C in a 16-liter fermentor or in a 1-liter culture to an optical density (A650) of 0.6. The medium was cooled to 30°C, and arabinose (1 mM) and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (0.1 mM) were added. Cultures were incubated for an additional 6 h at 30°C before they were harvested by centrifugation. Cell paste was flash frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Protein purification.

Frozen cell paste was weighed and suspended in an equal volume (wt/vol) of buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6) containing DNase (0.03 mg/ml). Cell suspensions were passed three times through a chilled French pressure cell at 4°C. Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation (39,000 × g for 40 min at 4°C). The clarified cell extract was loaded onto a preequilibrated Ni2+-loaded chelating Sepharose fast-flow (GE Healthcare) column (1.6 by 10 cm) and washed with 20 column volumes of buffer B. The column was again equilibrated with buffer A, and recombinant protein was eluted during a 30-column-volume linear gradient of from 0 to 100% elution buffer. Fractions that contained ApbE at >95% purity by SDS-PAGE analysis were pooled and concentrated over a 30,000-Da-molecular-mass-cutoff membrane (YM30; Amicon). After concentration, rApbE proteins were dialyzed overnight in buffer C. The final protein preparation was transferred by droplets into liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until needed. All steps were performed at 4°C, and buffers used for dialysis had the pH adjusted at 4°C. The rApbE protein was considered pure when 95% of the protein sample was rApbE, as judged by a silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel.

Reconstitution of rApbE holoprotein.

Purified rApbE protein was dialyzed against buffer C containing 1 mM FAD for 5 h, followed by dialysis against buffer C for 20 h with four buffer changes.

Quaternary structure determination.

The Stokes radius of ApbE was determined using a Superose 6 PC 3.2/30 size-exclusion column (GE Healthcare). Purified ApbE proteins were injected as 100 μl of a 5-mg/ml solution. The mobile phase for the analysis was 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 200 mM NaCl, and a flow rate of 0.1 ml/min was used. The standards used were purchased from Bio-Rad and are as follows: thyroglobulin (bovine, 670,000 Da), gamma globulin (bovine, 158,000 Da), ovalbumin (chicken, 44,000 Da), myoglobin (horse, 17,000 Da), and vitamin B12 (1,350 Da). The migration of the molecular mass protein standards were used to create a plot of log molecular mass of the standard versus retention time. The data were fit using linear regression and are described by the following equation (R2 > 0.99):

|

(1) |

where MM is the molecular mass of the protein, Te is the elution time, and To is the time taken to elute the void volume.

Protein concentration determination.

Protein concentration was determined by a copper-based colorimetric assay using a reagent containing bicinchoninic acid to detect the cupreous ion (Pierce). Bovine serum albumin (2 mg/ml) was used as a standard.

Mass spectral analysis of flavin.

A 200-μl aliquot of a 500 μM rApbE sample was incubated at 100°C for 10 min. The cofactor was separated from denatured rAbpE using a Centricon 10,000-Da-molecular-mass cutoff membrane (YM-10; Microcon). The filtrate and a FAD standard (30 μM) were subjected to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) analysis at the University of Wisconsin—Madison Biotechnology Center. Briefly, the samples were separated using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Agilent 1200 chromatograph) with a Zorbax SB-C18 column (2.1 by 50 mm; particle size, 1.8 μm) with a linear gradient of water/acetonitrile/formic acid from 980:20:1 to 100:900:1 over 25 min at 0.25 ml/min. The mass of the eluting flavins was measured by an Agilent LC/MSD (mass selective detector) time of flight (TOF) mass spectrometer using electrospray ionization in the negative-ion mode.

Protein FAD stoichiometry.

ApbE proteins were denatured using 6 M guanidinium hydrochloride. The protein was then separated from the buffer components using a 3,000-Da-molecular-mass-cutoff Centricon membrane (YM-3; Microcon). A spectrum of the filtrate was taken with a Lambda 40 UV-visible spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer). The FAD concentration was estimated using the published extinction coefficient (ɛ450), which is 11,400 M−1 cm−1 (31). Alternatively, rApbE was denatured by incubation at 100°C for 10 min and pelleted by centrifugation. A UV-visible spectrum of the supernatant was obtained, and the FAD concentration was calculated by use of the extinction coefficient.

Structure determination.

Crystals of ApbE (space group, P212121; cell dimensions, a = 65.10 Å, b = 120.85 Å, c = 212.06 Å) (Table 2) were grown under aerobic conditions at 4°C using the vapor diffusion method from solutions containing 0.5 M LiSO4, 18% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 4000 in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), and 10 to 20 mg/ml ApbE as purified FAD-bound ApbE. Crystals appeared within hours of initial setup and were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen on rayon loops, using glycerol as a cryoprotectant. Data were collected at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) beamline 9-1 at a wavelength of 0.9879 Å using a mar345 image plate, processed and integrated by use of the MOSFILM program (28), and subsequently scaled and merged with the CCP4 program package (Table 2) (12). On the basis of the nearly 80% amino acid sequence identity between E. coli ApbE and the S. enterica ApbE, a homology model of S. enterica ApbE was constructed using the coordinates of the E. coli ApbE dimer (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession number 2O18). The structure of AbpE from E. coli has not been published but has been made available in the Protein Data Bank through the efforts of the NorthEast Structural Genomics target and is designated target ER559A. The molecular replacement solution was obtained using CCP4 (12) with the aforementioned homology model as a search model. The solution had two dimers in the asymmetric unit and good packing, and a high correlation coefficient (above 0.5) was obtained. Subsequent building of the model manually was completed using the Coot program (version 0.1.2) (17). Refinement with CCP4 (REFMAC5 program, version 5.50109) (34) incorporating restrained thermal parameters, noncrystallographic symmetry (NCS) restraints, and 20 translation/libration/screw (TLS) groups resulted in a model with excellent geometry (root mean squared [RMS] deviations from ideal bond lengths = 0.005 Å and bond angles = 0.915°) and a high correlation with the crystallographic data (Rcryst = 20.5%, Rfree = 25.4%). Residues not included due to the absence of any electron density include chain A (20-31, 349-356), chain B (20-32, 234-240, 349-356), chain C (20-25, 349-356), and chain D (20-32, 235-240, 350-356). Figures 4 and 5 and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material were generated using the Pymol program (15).

TABLE 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Parametera | Value(s) |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions, a, b, c (Å) | 65.1, 120.8, 212.1 |

| Wavelength | 0.98789 |

| Resolution (Å) | 32.60-2.75 (2.82-2.75)b |

| No. of measured reflections | 183,946 |

| No. of unique reflections | 44,200 |

| Rmerge (%) | 9.3 (40) |

| I/σI | 14.1 (2.7) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (99.9) |

| Multiplicity | 4.2 (4.3) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 32.60-2.75 |

| No. of reflections | 41,979 |

| Rcryst/Rfree (%) | 20.5/25.4 |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein | 9,708 |

| SO4 (no. of molecules) | 220 (44) |

| FAD (no. of molecules) | 212 (4) |

| Water | 329 |

| Average B value | 26.6 |

| RMS deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.899 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%)c | |

| Most favored | 98.4 |

| Additional allowed | 1.60 |

Rmerge = 100ΣhΣi|Ii(h) − 〈I(h)〉|/ΣhI(h), where Ii(h) is the ith measurement of reflection and h and 〈I(h)〉 is the average value of the reflection intensity. Rcryst = Σ||Fo| − |Fc||/Σ|Fo|, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes used in refinement, respectively. Rfree is calculated as Rcryst but using the “test” set of structure factor amplitudes that were withheld from refinement.

Highest-resolution shell is shown in parentheses.

Calculated using Molprobity (13).

Protein structure accession number.

The coordinates for the structure described in this work have been submitted to the RCSB Protein Data Bank for release upon submission (PDB accession number 3PND).

RESULTS

Purification and biochemical analysis of recombinant ApbE.

The pApbE10 construct overproduces an ApbE variant (rApbE) with a C-terminal poly(His) tag that lacks the lipoprotein signal peptide and accumulates in the cytoplasm (5). The rApbE protein was highly expressed from this construct in Escherichia coli and accumulated to approximately 20% of the cellular proteins, as visualized by SDS-PAGE (data not shown).

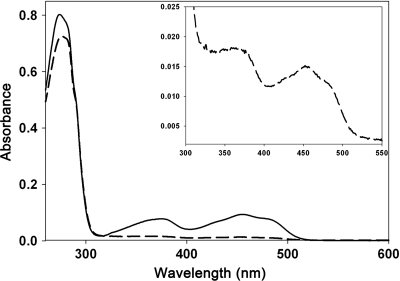

Purified rApbE had a light yellow color, and the UV-visible absorption spectrum showed absorbance peaks at 375 and 450 nm and resembled that of a flavin (Fig. 1, dashed line). The flavin cofactor was separated from rApbE using high-temperature incubation, followed by ultrafiltration. The filtrate was submitted for LC/MS analysis to determine the nature of the cofactor. As shown in Fig. 2, a peak that had a signal with an m/z of 784.15 eluted at 6.9 min. The same pattern was found when the FAD standard was subjected to this LC/MS protocol. These data identified FAD as the flavin that copurified with rApbE. On the basis of the UV-visible spectrum of rApbE as isolated, the ratio of FAD to rApbE monomer was estimated to be ∼0.1:1, suggesting that FAD remained associated with only a subset of the rApbE proteins after purification.

FIG. 1.

rApbE is a flavoprotein. The UV-visible absorption spectra of 15 μM rApbE before (dashed curve) and after (solid curve) reconstitution with FAD indicate that rApbE is a flavoprotein. (Inset) Magnification showing the relevant region of the UV-visible spectrum of the as-isolated rApbE.

FIG. 2.

FAD is released from purified rApbE. Authentic FAD (A) or flavin isolated from heat-denatured rApbE (B) was separated by LC. The peak eluting 6.94 min after injection was analyzed by electrospray ionization using a tandem in-line TOF mass spectrometer, and the mass/charge ratios are expressed as atomic mass units (amu) (insets).

rApbE is a FAD-binding protein.

Purified rApbE protein was dialyzed against 1 mM FAD for 5 h, followed by dialysis against buffer without FAD to remove unbound or weakly bound cofactor. The UV-visible spectrum of reconstituted protein had spectral properties characteristic of bound FAD (Fig. 1). Reduction of the reconstituted protein with 1 mM dithionite bleached the absorbance peaks at 375 nm and 450 nm, consistent with the assignment of these peaks to FAD (data not shown). The comparatively weak spectral signals in the as-isolated rApbE suggested that the interaction between protein and FAD was disrupted by the affinity purification protocol. Samples of the as-isolated and reconstituted protein were denatured using 6 M guanidinium hydrochloride, and small molecules were removed by ultrafiltration. The concentrated protein solution did not absorb in the 300- to 500-nm region, consistent with FAD being noncovalently bound to rApbE. Quantitation of the FAD released by the denaturation of the rApbE protein indicated that after reconstitution, 0.7 ± 0.1 mol of FAD was bound per rApbE monomer. This number likely reflects 1 mol of FAD per monomer and is consistent with the structural data.

rApbE protein purifies as a dimer.

The quaternary structures of the as-isolated and FAD-reconstituted forms of rApbE were analyzed by size-exclusion chromatography. In both cases the protein migrated as one predominant peak, indicating an oligomeric species with an estimated molecular mass of 52 kDa (Fig. 3). The predicted size of poly(His) rApbE is 36 kDa, suggesting that, as purified, rApbE is a homodimer, a conclusion also reached with the structural data. We assume that the native membrane-bound form of ApbE would have the same oligomeric state determined for the cytoplasmic variant determined here.

FIG. 3.

rApbE protein is a dimer in solution. A plot of the log of known molecular mass markers (filled circles) versus the time taken for samples to elute from the column (Te/To) was used to determine the approximate size of the rApbE protein. The line shown is the fit to equation 1, which was used to conclude that FAD-reconstituted rApbE protein (empty square) has a Stokes radius constant with a molecular mass of approximately 52 kDa. The standards used were thyroglobulin (bovine, 670,000 Da), gamma globulin (bovine, 158,000 Da), ovalbumin (chicken, 44,000 Da), myoglobin (horse, 17,000 Da), and vitamin B12 (1,350 Da). (Inset) ApbE (0.5 mg) protein as isolated or after reconstitution with FAD (as shown) migrated as a single predominant species. The gel filtration conditions are as follows: solid phase, Superose 6; mobile phase, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 200 mM NaCl; flow rate, 0.1 ml/min.

X-ray structure of rApbE.

The structure of rApbE with FAD bound has been determined and refined to a resolution of 2.75Å (Fig. 4A; Table 2). Superimposition of the corresponding C-α positions of the S. enterica and E. coli ApbE (PDB accession number 2O18) monomers results in an RMS deviation of 0.816 Å. The quaternary structure of rApbE is comprised of two subunits forming a dimer with a subunit interface analogous to the structure of the E. coli enzyme in the database (PDB accession number 2O18) (Fig. 4A). The rApbE dimer binds two molecules of FAD, one molecule per monomer (Fig. 4A). The bound FAD molecules are located distal to the dimer interface in the quaternary structure (Fig. 4B). The final model of S. enterica rApbE contains 44 surface-associated sulfate ions, and including these sulfate ions in the model improves the refinement.

FIG. 4.

(A) Ribbon diagram of the rApbE dimer showing one FAD molecule bound per rApbE monomer related to the primary sequence. (B) Ribbon diagram of the rApbE monomer with FAD bound. The FAD is shown as a sphere representation. The phosphates are shown in magenta. (C) Ribbon diagrams of the rApbE monomer. The α helices are shown in purple, and the β sheets are shown in green. The residues of the FAD-binding site are shown in blue stick representation and are indicated on the sequence. The residues comprising the dimer interface are shown in salmon as a stick representation and are indicated on the sequence. Residues Ser76, Thr184, and Gly255 are indicated by black dots; and Tyr78, which was targeted for mutagenesis, is indicated by a black star.

The rApbE dimer interface results from four major interactions between individual monomers (Fig. 4A and C). The interface is formed by contacts between 23 residues, the majority of which lie in the first flanking α helix and the second core antiparallel β sheet of each subunit (Fig. 4C). Each monomer is comprised of a core of eight antiparallel β sheets flanked by eight α helices that can be described as a tunneling fold (T-fold) core. A 110-residue portion of the N terminus (residues 76 to 185) forms a long α helix followed by a β hairpin that largely accounts for the dimer interface. Residues of the first α helix that form a portion of the dimer interface include Glu100, Asp104, Thr107, Leu110, Arg111, Ala114, and Lys115 (Fig. 4C). In addition, residues Glu158, Gln161, Val162, Ile163, Asp164, Arg165, and Ala166 of the second core antiparallel β sheet of each monomer are located at the opposite side of the dimer interface formed by the contacts between the α1 hlix of each monomer. The rest of the dimer interface consists of residues from the α5 helix (Asp245, Asn247, Gly248, Glu249, Glu199, Gln200, and Gly202) and residues Gln340 and Thr343 from α8, the flanking α helix (Fig. 4C). The majority of interface interactions between monomer subunits are comprised of residues from the first α helix and separately from the second antiparallel β sheet.

The rApbE monomer was cocrystallized with FAD, resulting in one FAD molecule bound per monomer (Fig. 4A and B). Analysis of Fo − Fc electron density maps (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) shows clear electron density for the atoms comprising the FAD molecule bound by each rApbE monomer. The 110-residue portion of the N terminus (residues 76 to 185) that accounts for the majority of the dimer interface also contains residues that account for a number of the contacts with FAD, along with key residues of β1 and α4 (Fig. 4C). A loop and β hairpin formed by residues 217 to 249 pack against the C-terminal β sheet to bury the adenine portion of FAD, and an additional C-terminal loop prevents solvent exposure (Fig. 5A). The FAD adopts a semicircular conformation wherein the adenine and FAD portions are largely buried and the phosphates are more solvent exposed. The isoalloxazine base of FAD is located in a pocket formed between the first strand of the antiparallel β sheet and the first α helix, with residues Met41, Gly42, Asp72, Ser76, Asp181, Ser183, and Glu187 forming a pocket (Fig. 5A and B). The flavin is positioned in a loop in the β sheet structure, with the side chain of Met41 extending parallel to the long axis of the isoalloxazine base. This interaction together with the interaction from Tyr78, which packs against the other face of the FAD isoalloxazine moiety, sandwich the base and lock it into place. The backbone carbonyl groups of Met41 and Glu187 are in position to hydrogen bond to the proximal hydroxyl of the ribitol (3.2 Å, 3.0 Å) (Fig. 5A). The carboxyl groups of Asp181 and Ser183 hydrogen bond with the middle hydroxyl of the isoalloxazine proximal ribitol (2.6 Å, 3.2 Å) (Fig. 5C). The phosphates are located in the environment of the polar side chains of Ser183, Glu187, and Arg267 (Fig. 5C). The adenine lies in a pocket formed by N- and C-terminal α helices and residues Ala119, Glu121, Arg267, and Ile272 (Fig. 5D). The direct hydrogen-bonding interactions that stabilize adenine occur predominantly through interactions with the protein backbone. The backbone amide carbonyl oxygen of Ala119 and the backbone amide nitrogen of Ile272 hydrogen bond to N-6 of the adenine. Additional interactions occur between the amide nitrogen of Ile272 and N-7 and between the amide group of Asp 121 and N-1 of the adenine. A loop region formed by residues 268 through 286 forms a binding pocket and limits solvent exposure of the adenosine portion of the FAD molecule.

FIG. 5.

(A) Stereo view of the FAD-binding site in the rApbE monomer. Residues interacting with the FAD isoalloxazine ring (B), phosphates (C), and the adenine (D) are shown in line angle representations.

Mutagenesis targets residues critical for function.

Local mutagenesis was used in an effort to identify residues required for rApbE function in vivo. A P22 lysate grown on strain DM3417 (yojI::mudJ) was mutagenized with hydroxylamine and used to isolate mutations linked to the MudJ that caused a thiamine auxotrophy. The relevant mutations from 13 isolates were reconstructed. Sequence analysis determined that each of the 13 mutations was in the apbE gene. Of the 11 nucleotide changes found, 8 generated nonsense codons: Q221Z (apbE171), Q199Z (apbE172; isolated twice), Q33Z (apbE180), Q230Z (apbE182), Q182Z (apbE184; isolated twice), Q230Z (apbE185), Q241Z (apbE187), and W182X (apbE188). The remaining three mutations were base substitutions that resulted in variant proteins S76F (apbE181), G255S (apbE183), and T184M (apbE186). Western hybridizations with polyclonal antibodies against ApbE indicated that the three variant proteins accumulated to the same extent as the wild-type protein in vivo (data not shown). This result indicated that the nutritional phenotype caused by the mutations resulted from changes to the protein that affected in vivo activity and not the stability of the protein.

Each of the three missense mutations was introduced into pApbE10 by site-directed mutagenesis, resulting in plasmids pJMB131 (apbE181), pJMB132 (apbE183), and pJMB133 (apbE187). Upon purification, the variants had a yellow hue similar to the wild-type protein. The purified variants were immobilized on a Ni column, and buffer containing FAD (0.5 mM) was passed over the column, prior to extensive washing with buffer alone. Subsequently, the proteins were eluted off the column and bound FAD was quantified. Under the single in vitro condition tested, each of the three variants retained ∼0.6 to 0.7 mol FAD per mole protein, as did the wild-type protein. Nonetheless, the position of the variant residues in the crystal structure (Fig. 4C) suggests that they could affect the FAD interactions with the protein in a subtle way, despite the generally wild-type behavior in vitro.

Loss of FAD binding correlates with loss of function in vivo.

Inspection of the X-ray structure of rApbE revealed conserved residues expected to contribute to the binding of FAD. The position of the Y78 residue with the riboflavin moiety of the FAD molecule predicted that this residue was responsible for FAD coordination. Analysis of the primary amino acid sequences of ApbE proteins found that the presence of an aromatic amino acid (Tyr or Trp) is conserved at this position and strengthened the hypothesis that a pi-stacking interaction was required for FAD binding. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to construct vectors that encoded the full-length (periplasmic, pJMB129) and truncated (cytoplasmic, pJMB130) poly(His) forms of ApbEY78A.

The function of the full-length ApbEY78A variant in vivo was tested by complementation of an apbE null mutant strain, and the data are shown in Fig. 6. Strain DM9722 with pSU19 (empty vector) was unable to grow in minimal glucose medium due to the thiamine requirement of an apbE mutant. The presence of pApbE1 (wild-type ApbE) restored growth of strain DM9722 in minimal glucose medium, whereas the presence of pJMB129 (ApbEY78A) did not. All strains grew equally well when thiamine was provided in the medium.

FIG. 6.

The ApbEY78A variant is not functional in vivo. Growth of S. enterica strain DM9722 with pJMB129 (ApbEY78A; squares), pApbE1 (ApbE; circles), or pSU19 (empty vector; triangles) in minimal glucose medium supplemented with adenine is shown. Growth of the strains is shown as the absorbance at 650 nm over time in the presence of 100 nM thiamine (filled symbols) and with no thiamine added (open symbols). Variant proteins accumulated to levels that were indistinguishable from those of the wild-type protein by Western blot analysis (see text).

Wild-type rApbE and the rApbEY78A protein variants were purified in parallel and the FAD binding was characterized. No FAD was associated with the rApbEY78A variant as isolated, while the wild type contained ∼0.1 mol/mol FAD per rApbE monomer. The wild-type and Y78A proteins were dialyzed in parallel against buffer with FAD and then against buffer without FAD, and the amount of FAD bound to the proteins was quantified. The wild-type rApbE and rApbEY78A variant bound 0.6 and <0.1 mol of FAD per monomer, respectively (Fig. 7). Taken together, these data indicate a role for the FAD in the cellular function of ApbE.

FIG. 7.

The rApbEY78A variant is defective in FAD binding. The UV-visible absorption spectra of wild-type rApbE (12 μM; solid line) and the Y78A rApbE variant (12 μM; dashed line) are shown. The proteins were reconstituted as described in the text. Without reconstitution, no absorbance in the 300- to 500-nm range was seen with the rApbEY78A variant.

DISCUSSION

S. enterica ApbE belongs to a conserved family of proteins that includes RnfF and NosX. Past in vivo work implicated ApbE as a membrane-associated periplasmic protein involved in metabolism of Fe-S clusters and led to the hypothesis that ApbE had a role in electron transfer during the synthesis and/or repair of Fe-S clusters (5, 6, 38). The study described here was initiated to probe the biophysical properties of ApbE to provide insights into the in vivo function of the protein. The crystal structure of the S. enterica rAbpE presented here supports the observation that the protein is a homodimer, as implicated by chromatography. The primary sequence conservation between S. enterica rApbE and E. coli ApbE in residues involved in intermolecular interactions at the dimer interface support the suggestion that rApbE exists as a homodimer. The binding of numerous buffer sulfate molecules may support the membrane association and may indicate binding sites of phosphate head groups of phospholipids that facilitate association with the membrane. Probably most significant, these structural studies have provided the first biophysical data that a member of the ApbE family is a flavoprotein defining a new FAD-binding motif. The mutational analyses presented here define residues critical for in vivo function and support a role for FAD in the activity of the protein.

Four families of FAD-binding proteins have been identified, although recent evidence has revealed novel FAD-binding folds that do not fall into these four families (16, 20). Many of the FAD-binding folds noted to date are found in FAD-binding proteins that do not share significant primary sequence homology; however, conserved residues are found in the FAD-binding sites (16, 18). The glutathione reductase (GR) family of FAD-binding proteins adopts the Rossman fold and binds FAD in an extended conformation, with the adenine ring being in the FAD-binding domain and the isoalloxazine ring being distal (16, 37). The FAD-binding fold of the ferredoxin reductase (FR) family consists of a cylindrical β sheet wherein the isoalloxazine ring of FAD is located (26). The only α helix of this domain caps the cylindrical β sheet and interacts with the phosphates. The p-cresol methylhydroxylase (PCMH) structural family binds FAD between two α and β subdomains, with the FAD being in an elongated conformation (16). In the pyruvate oxidase (PO) family, FAD is bound perpendicular to a core of β strands in an elongated conformation (16).

The X-ray crystal structure of rApbE presented here reveals one FAD bound per monomer distal to the dimer interface. The rApbE monomer consists of an eight-stranded antiparallel β sheet core flanked by eight α helices comprising a T-fold core that was also identified in the structure of ApbE from Thermatoga maritima MSB8 (PDB accession number 1VRM) (21). Proteins having the T-fold have been implicated as supporting interactions that result in oligomerization, and although the biochemical data on S. enterica do not suggest oligomerization, the crystal contact interactions in the vicinity are quite extensive. In addition to the T-fold core, the rApbE momomer also contains a novel fold that is associated with the FAD-binding domain. This fold was also identified in the structure from T. maritima; however, it was not correlated to a FAD-binding domain. In rApbE from S. enterica, FAD adopts a semicircular confirmation in the binding region with the isoalloxazine ring buried in a pocket formed largely by residues of the first flanking α helix. Key residues of the FAD-binding domain of rApbE, such as Gly42 that accommodates the flavin and the aromatic Tyr78 that packs against the face of the isoalloxazine ring, are conserved among homologous FAD-binding proteins. The base stacking of the isoalloxazine ring by aromatic residues is observed in the majority of FAD-binding proteins to date, despite the diversity in the secondary structures of these proteins. However, in many other FAD-binding proteins, both faces of the isoalloxazine ring are packed by another conserved aromatic residue (20), a feature that is not observed in S. enterica rApbE. In addition, polar residues positioned to interact with the phosphates are common to FAD-binding folds, regardless of the conformation adopted by FAD (16, 20). A DALI program (23) search for folds similar to the fold of S. enterica rApbE with FAD bound revealed a high degree of similarity to the E. coli ApbE (PDB accession number 2O18) and weak matches to ApbE from T. maritima (PDB accession number 1VRM) and a hypothetical protein from Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough (PDB accession number 2O34). Although FAD binding in these homologs has not been characterized, electron density attributed to an unknown ligand was modeled into the T. maritima structure (21). The X-ray crystal structure of S. enterica rApbE with FAD bound has revealed a novel FAD-binding domain, defining what can be categorized as a new class of FAD-binding proteins.

Local mutagenesis in vivo yielded an unexpected number of nonsense mutations in apbE. Wild-type ApbE is 350 amino acids long, and of the 13 mutations isolated as thiamine auxotrophs, 10 generated termination codons that resulted in truncated proteins of 34 to 240 amino acids in length. The expectation was that ∼5% of the mutations would be nonsense codons, and the significant overrepresentation suggests that a complete loss of function of ApbE was required to generate the phenotype screened (i.e., thiamine auxotrophy). On the basis of this interpretation, the three missense mutations that were found (S76F, T184M, G255S) are likely to identify single residues critical for function. All the variant residues are located in the environment of FAD (Fig. 4C); however, none are involved in direct interactions. Ser76, as mentioned above, is part of a polar pocket that surrounds the FAD isoalloxazine base, and although it is not directly interacting, the γ-O of Ser is within 3.7 Å of N-5 of the middle ring of the base. In addition, this Ser is in close proximity to the critical Tyr residue (Tyr78) involved in base stacking interactions with isoalloxazine. Targeted mutagenesis of the tyrosine residue that coordinates the FAD in the structure generated a variant that was inactive in vivo and unable to bind FAD in vitro. Thr184 and Gly255 lie in the environment of FAD close to the adenine proximal ribose moiety, with the γ-O of Thr being within 4.9 Å of a ribose hydroxyl group. Despite the location of these residues in the environment of FAD, the variant proteins were not defective in FAD binding when binding was assessed in vitro. This result suggests that the in vivo environment modulates the defect in subtle ways that cannot be detected by simply monitoring the FAD associated with the protein.

Collectively, the data presented here strongly implicate a role for FAD in the function of ApbE and furthered the hypothesis that ApbE is involved in electron transfer in the role of synthesis and/or repair of Fe-S cluster proteins. To our knowledge, this is the first report of functional analyses of single amino acid variants in this protein family. The mutant analysis and structural studies described here continue to ongoing studies probing the function of ApbE family members implicated in various cellular processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The apbE alleles characterized herein were generated by Mike Huelsmeyer when he was an undergraduate in the laboratory of Diana M. Downs.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant GM47296 to D.M.D.), the U.S. Department of Energy (grant DE-FG02-04ER15563 to J.W.P.), and a Kirschstein postdoctoral training grant (GM079938-02 [to J.M.B.]) from the NIH. Funds were also provided from a 21st Century Scientists Scholars Award from the J. M. McDonnell fund to D.M.D. Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 December 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agar, J. N., et al. 2000. IscU as a scaffold for iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis: sequential assembly of [2Fe-2S] and [4Fe-4S] clusters in IscU. Biochemistry 39:7856-7862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Backiel, J., et al. 2008. Covalent binding of flavins to RnfG and RnfD in the Rnf complex from Vibrio cholerae. Biochemistry 47:11273-11284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balch, W. E., and R. S. Wolfe. 1976. New approach to the cultivation of methanogenic bacteria: 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid-dependent growth of Methanobacterium ruminantium in a pressurized atmosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 32:781-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartolomé, B., Y. Jubete, E. Martinez, and F. de la Cruz. 1991. Construction and properties of a family of pACYC184-derived cloning vectors compatible with pBR322 and its derivatives. Gene 102:75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck, B. J., and D. M. Downs. 1998. The apbE gene encodes a lipoprotein involved in thiamine synthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 180:885-891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck, B. J., and D. M. Downs. 1999. A periplasmic location is essential for the role of the ApbE lipoprotein in thiamine synthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 181:7285-7290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkowitz, D., J. M. Hushon, H. J. Whitfield, J. Roth, and B. N. Ames. 1968. Procedure for identifying nonsense mutations. J. Bacteriol. 96:215-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertani, G. 2004. Lysogeny at mid-twentieth century: P1, P2, and other experimental systems. J. Bacteriol. 186:595-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertani, G. 1951. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 62:293-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd, J. M., J. L. Sondelski, and D. M. Downs. 2009. Bacterial ApbC protein has two biochemical activities that are required for in vivo function. J. Biol. Chem. 284:110-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan, Y. K., W. A. McCormick, and R. J. Watson. 1997. A new nos gene downstream from nosDFY is essential for dissimilatory reduction of nitrous oxide by Rhizobium (Sinorhizobium) meloti. Microbiology 143:2817-2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collaborative Computational Project, N. 1994. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50:760-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis, I. W., et al. 2007. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:W375-W383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis, R. W., D. Botstein, J. R. Roth, and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. 1980. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 15.DeLano, W. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. PyMOL, Shrödinger, LLC, New York, NY. http://www.pymol.org.

- 16.Dym, O., and D. Eisenberg. 2001. Sequence-structure analysis of FAD-containing proteins. Protein Sci. 10:1712-1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emsley, P., and K. Cowtan. 2004. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60:2126-2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraaije, M. W., W. J. Van Berkel, J. A. Benen, J. Visser, and A. Mattevi. 1998. A novel oxidoreductase family sharing a conserved FAD-binding domain. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:206-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gralnick, J. A., and D. M. Downs. 2003. The YggX protein of Salmonella enterica is involved in Fe(II) trafficking and minimizes the DNA damage caused by hydroxyl radicals: residue CYS-7 is essential for YggX function. J. Biol. Chem. 278:20708-20715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross, E., C. Sevier, A. Vala, C. Kaiser, and D. Fass. 2002. A new FAD-binding fold and intersubunit disulfide shuttle in the thiol oxidase Erv2p. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:61-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han, G. W., et al. 2006. Crystal structure of the ApbE protein (TM1553) from Thermotoga maritima at 1.58 Å resolution. Proteins 64:1083-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hefti, M. H., J. Vervoort, and W. J. van Berkel. 2003. Deflavination and reconstitution of flavoproteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 270:4227-4242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holm, L., and C. Sander. 1996. The FSSP database: fold classification based on structure-structure alignment of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:206-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong, J. S., and B. N. Ames. 1971. Localized mutagenesis of any specific small region of the bacterial chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 68:3158-3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juhnke, H. D., H. Hiltscher, H. R. Nasiri, H. Schwalbe, and C. R. Lancaster. 2009. Production, characterization and determination of the real catalytic properties of the putative ‘succinate dehydrogenase’ from Wolinella succinogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 71:1088-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karplus, P. A., M. J. Daniels, and J. R. Herriott. 1991. Atomic structure of ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase: prototype for a structurally novel flavoenzyme family. Science 251:60-66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koo, M. S., et al. 2003. A reducing system of the superoxide sensor SoxR in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 22:2614-2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leslie, A. G. W. 1992. Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing files and image plate data. Joint CCP4 + ESF-EAMCB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography, no. 26.

- 29.Lewis, J. A., and J. C. Escalante-Semerena. 2007. Tricarballylate catabolism in Salmonella enterica. The TcuB protein uses 4Fe-4S clusters and heme to transfer electrons from FADH2 in the tricarballylate dehydrogenase (TcuA) enzyme to electron acceptors in the cell membrane. Biochemistry 46:9107-9115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loo, C. Y., et al. 2004. Role of a nosX homolog in Streptococcus gordonii in aerobic growth and biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 186:8193-8206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macheroux, P. 1999. UV-visible spectroscopy as a tool to study flavoproteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 131:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massey, V. 2000. The chemical and biological versatility of riboflavin. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 28:283-296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mikoulinskaia, O., V. Akimenko, A. Galouchko, R. K. Thauer, and R. Hedderich. 1999. Cytochrome c-dependent methacrylate reductase from Geobacter sulfurreducens AM-1. Eur. J. Biochem. 263:346-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murshudov, G. N., A. A. Vagin, and E. J. Dodson. 1997. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53:240-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neumann, M., et al. 2009. A periplasmic aldehyde oxidoreductase represents the first molybdopterin cytosine dinucleotide cofactor containing molybdo-flavoenzyme from Escherichia coli. FEBS J. 276:2762-2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmehl, M., et al. 1993. Identification of a new class of nitrogen fixation genes in Rhodobacter capsulatus: a putative membrane complex involved in electron transport to nitrogenase. Mol. Gen. Genet. 241:602-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulz, G. E., R. H. Schirmer, and E. F. Pai. 1982. FAD-binding site of glutathione reductase. J. Mol. Biol. 160:287-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skovran, E., and D. M. Downs. 2003. Lack of the ApbC or ApbE protein results in a defect in Fe-S cluster metabolism in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 185:98-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vogel, H. J., and D. M. Bonner. 1956. Acetylornithase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J. Biol. Chem. 218:97-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wunsch, P., and W. G. Zumft. 2005. Functional domains of NosR, a novel transmembrane iron-sulfur flavoprotein necessary for nitrous oxide respiration. J. Bacteriol. 187:1992-2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.