Abstract

The first allele of a 16S rRNA methyltransferase gene, rmtD2, conferring very high resistance to all clinically available aminoglycosides, was detected in 7/1,064 enterobacteria collected in 2007. rmtD2 was located on a conjugative plasmid in a Tn2670-like element inside a structure similar to that of rmtD1 but probably having an independent assembly. rmtD2 has been found since 1996 to 1998 mainly in Enterobacter and Citrobacter isolates, suggesting a possible reservoir in these genera. This presumption deserves monitoring by continuous surveillance.

Posttranscriptional methylation of the 16S rRNA aminoglycoside binding site, common in aminoglycoside-producing microorganisms, has been described in nosocomial isolates highly resistant to all clinically available aminoglycosides. Currently, seven plasmid-mediated 16S rRNA methyltransferase (16S-methylase) genes have been identified: armA, npmA, rmtA, rmtB, rmtC, rmtD (named rmtD1 herein), and very recently, rmtE, from bovine origin (3, 4, 19). To date, only Klebsiella pneumoniae harboring rmtD1 has been reported in Argentina (7). Herein, a nationwide survey of aminoglycoside resistance mediated by 16S-methylases among enterobacteria in Argentina was performed.

(Preliminary data were presented in abstract form at the 109th General Meeting, American Society for Microbiology, 2009, and at the 50th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, American Society for Microbiology, 2010.)

Susceptibility and molecular detection of resistance mechanisms.

To determine the prevalence of the 16S-methylases, a collection of 1,064 consecutive, nonduplicate enterobacterial isolates was analyzed. This sample set was collected during a 5-day period in 2007 from 66 hospitals belonging to the WHONET-Argentina Resistance Surveillance Network and submitted to the Servicio Antimicrobianos (the Argentinian National Reference Laboratory). Initial screening of 16S-methylase activity was performed using the disc diffusion susceptibility method for amikacin and gentamicin (inhibition zones of ≤10 mm) (1, 4). Although almost 80% of the collection was made up of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp., only 12 isolates belonging to other species (4 Enterobacter cloacae, 1 Enterobacter aerogenes, 3 Serratia species, 2 Citrobacter freundii, 1 Morganella morganii, and 1 Proteus mirabilis isolate) met the screening criteria used. Of these, 5 showed inhibition zones of ≥7 mm to amikacin, and 7 (all of the Enterobacter species and C. freundii isolates) showed an absence of inhibition zones for both aminoglycosides. Only these last 7 isolates gave positive results when tested for 16S-methylase genes by PCR (Table 1), and only the primers against rmtD genes rendered amplicons (Table 2). Complete gene amplification and DNA sequencing showed a unique 16S-methylase gene in these 7 isolates. This gene displayed 97.3% nucleotide identity (20 nucleotides of difference) and 96.4% amino acid identity (9 residues of difference) with rmtD1. Since this is the first description of a 16S-methylase gene allele, it was named rmtD2, as recommended by Doi and colleagues (6). The rmtD2-harboring isolates were from 6 hospitals in 4 geographic areas across Argentina, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of XbaI-digested DNA of the 4 E. cloacae and 2 C. freundii isolates showed that they were not clonally related (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primers used for specific gene detection

| Targeta | Primer nameb | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Size (bp) | Ta (°C)c | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| armA | armA-F | AGGTTGTTTCCATTTCTGAG | 405 | 51 | This work |

| armA-R | ACCTATACTTTATCGTCGTC | ||||

| rmtA | rmtA-F | CGTGACATAACATCTGTATG | 333 | 51 | This work |

| rmtA-R | TTCAAATTCATCAGGCAGTG | ||||

| rmtB | rmtB-F | ATTGGGATTTTACCTTTGCC | 290 | 51 | This work |

| rmtB-R | TATAAGTTCTGTTCCGATGG | ||||

| rmtC | rmtC-F | AGATACCAAATCCAACTACG | 369 | 51 | This work |

| rmtC-R | TAAGTAGAAGATCACTCTCG | ||||

| rmtD | rmtD-F | TCAAAAAGGAAAAGGACGTG | 500 | 51 | This work |

| rmtD-R | CGATGCGACGATCCATTC | ||||

| rmtD-F2d | ATGAGCGAACTGAAGGAAAAAC | 744 | 57 | This work | |

| rmtD-R2d | TCATTTTCGTTTCAGCACGTAAA | ||||

| npmA | npmA-F | CTCAAAGGAACAAAGACGG | 641 | 51 | 7 |

| npmA-R | GAAACATGGCCAGAAACTC | ||||

| blaTEM | tem1-F | ATGAGTATTCAACATTTTCGTG | 861 | 55 | This work |

| tem1-R | TTACCAATGCTTAATCAGTGAG | ||||

| blaSHV | shv1-F | ATGCGTTATATTCGCCTGTG | 861 | 55 | This work |

| shv1-R | TTAGCGTTGCCAGTGCTCG | ||||

| blaCTX-M | ctx-MU1 | ATGTGCAGYACCAGTAARGT | 803 | 55 | 13 |

| ctx-MU2 | TGGGTRAARTARGTSACCAG | ||||

| blaKPC | Uni-KPC-F | ATGTCACTGTATCGCCGTCT | 882 | 55 | 17 |

| Uni-KPC-R | TTACTGCCCGTTGACGCCC | ||||

| qnrB | qnrB-F | CCGACCTGAGCGGCACTGA | 523 | 55 | 18 |

| qnrB-R | CGCTCCATGAGCAACGATGCCT |

rmtE was reported after the conclusion of this work, and its analysis was not included.

F, forward; R, reverse.

Ta, PCR annealing temperature.

Primers to amplify the complete rmtD gene.

TABLE 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility and molecular typing of resistance mechanisms of clinical isolates and transconjugant strains

| Antimicrobial agent or genetic determinanta | MIC (μg/ml) or molecular typing resultb |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor clinical isolatesc |

E. coli transconjugant strainsd |

E. coli transf.e |

E. coli acceptors |

||||||||||||||

| Ecl Q4010 | Ecl Q3039 | Ecl Q2054 | Ecl Q5161 | Cfr Q1174 | Cfr Q4143 | Eae Q4079 | ER-4010 | ER-3039 | J-2054 | J-5161 | J-1174 | J-4143 | J-4079 | ER1793 | J53 | ||

| Antimicrobial susceptibility testing | |||||||||||||||||

| AMK | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| GEN | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | 256 | 256 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | 256 | ≥1,024 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | 768 | 768 | 256 | ≥256 | 0.125 | 1.5 |

| KAN | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | 0.75 | 2 |

| NET | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| TOB | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | ≥1,024 | 768 | 256 | ≥1,024 | ≥256 | 256 | ≥256 | ≥1,024 | 256 | 256 | ≥256 | 0.094 | 1 |

| APR | 8 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4 | 4 |

| AMP | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | 64 | ≥256 | 48 | ≥256 | 96 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ND | 6 | 6 |

| PIP | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | 8 | 16 | 6 | ≥256 | 4 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ND | 1 | 2 |

| FOX | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | 2 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 16 | ND | 8 | 8 |

| CAZ | 192 | ≥256 | 128 | ≥256 | ≥256 | 24 | 12 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.19 | 8 | 16 | ND | 0.125 | 0.19 |

| CTX | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | 0.047 | 0.064 | 0.094 | 0.38 | 0.094 | 192 | ≥256 | ND | 0.094 | 0.094 |

| FEP | 6 | 192 | 4 | 24 | 12 | 256 | 128 | 0.094 | 0.094 | 0.125 | 0.38 | 0.094 | 24 | 48 | ND | 0.047 | 0.064 |

| IPM | 0.75 | 1.5 | 2 | 2 | 0.75 | 0.38 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.25 | ND | 0.25 | 0.38 |

| ERT | 8 | 24 | 16 | ≥32 | 6 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.032 | 0.023 | ND | 0.016 | 0.008 |

| MEM | 1 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 3 | 3 | 0.25 | 0.094 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.032 | 0.047 | 0.023 | ND | 0.023 | 0.023 |

| CIP | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | 0.19 | 0.125 | 0.19 | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.75 | 0.016 | ND | 0.125 | 0.012 |

| TET | 48 | 48 | 96 | 256 | 256 | 48 | 24 | 1.5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ND | 0.5 | 1 |

| CHL | 256 | 96 | 128 | 256 | ≥256 | 24 | ≥256 | 12 | 24 | 16 | 16 | 48 | 48 | ≥256 | ND | 3 | 6 |

| PCR | |||||||||||||||||

| armA | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| rmtA | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| rmtB | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| rmtC | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| rmtD | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ND | ND | ND |

| npmA | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| blaTEM | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | ND | ND | ND | − | + | ND | ND | ND |

| blaSHV | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| blaKPC | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| blaCTX-M | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | ND | ND | ND | + | ND | + | + | ND | ND | ND |

| qnrB | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | ND |

AMK, amikacin; GEN, gentamicin; KAN, kanamycin; NET, netilmicin; TOB, tobramycin; APR, apramycin; AMP, ampicillin; PIP, piperacillin; FOX, cefoxitin; CAZ, ceftazidime; CTX, cefotaxime; FEP, cefepime; IPM, imipenem; ERT, ertapenem; MEM, meropenem; CIP, ciprofloxacin; TET, tetracycline; CHL, chloramphenicol.

+ and −, positive and negative amplification, respectively; ND, not determined.

Ecl, E. cloacae; Cfr, C. freundii; Eae, E. aerogenes.

Transconjugant strains are designated with the letter from the acceptor E. coli strain (ER- and J- indicate derivation from E. coli ER1793 and J53, respectively) and the number from the donor clinical strain.

E. coli transformed with the rmtD2 gene.

Antibiotic MICs, except that of apramycin (agar dilution method [1]), were determined by Etest (AB bioMérieux, Solna, Sweden). The 7 rmtD2-harboring isolates showed high MICs to all of the aminoglycosides tested except apramycin (Table 2). These results were comparable with those of Fritsche and colleagues for enterobacteria producing different enzymes that methylate the 16S rRNA at position G1405 (7). Conversely, Wachino and colleagues described NpmA, which methylates at position A1408, conferring intermediate resistance to amikacin (16 μg/ml) and low-level resistance to gentamicin (32 μg/ml) but high-level resistance to apramycin (>256 μg/ml) (19). Taken together, these data suggest that the new variant RmtD2 methylates at position G1405. Moreover, our phenotypic results support the approach of Doi and Arakawa for detecting the 16S-methylases that act at that last position (4).

The rmtD2-harboring isolates displayed other resistance mechanisms (Table 2). Under the new carbapenem breakpoints (2), all 7 clinical strains showed resistance/intermediate resistance to ertapenem, and several of them showed intermediate resistance to imipenem and/or meropenem. This is probably due to impermeability combined with hyperproduced AmpC and/or CTX-M-type enzymes (11, 16). Production of metallo-β-lactamases was discarded by EDTA-sodium mercaptoacetic acid (SMA) phenotypic screening (8). All of the isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin (Q4079 showed reduced susceptibility), tetracycline, and chloramphenicol as well. Biparental conjugations were performed between each rmtD2-harboring clinical isolate and sodium azide-resistant E. coli J53 or rifampin- and nalidixic acid-resistant E. coli ER1793 as recipients, using amikacin (50 μg/ml) and gentamicin (50 μg/ml) plus sodium azide (100 μg/ml) or rifampin (300 μg/ml), respectively, to select the transconjugants. All conjugations rendered rmtD2-harboring transconjugants highly resistant to aminoglycosides (Table 2). Resistance to ampicillin, piperacillin, extended-spectrum cephalosporins, and chloramphenicol was cotransferred to E. coli in some cases. Transmission of reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin was observed in the transconjugant J-4143. The characterization of relevant genetic determinants responsible for these resistant phenotypes, such as blaTEM-1, blaCTX-M-2, and qnrB10, was performed by PCR and DNA sequencing (Tables 1 and 2). Therefore, RmtD2 was coexpressed with, but not necessarily linked to, other resistance mechanisms.

rmtD2 flanking regions.

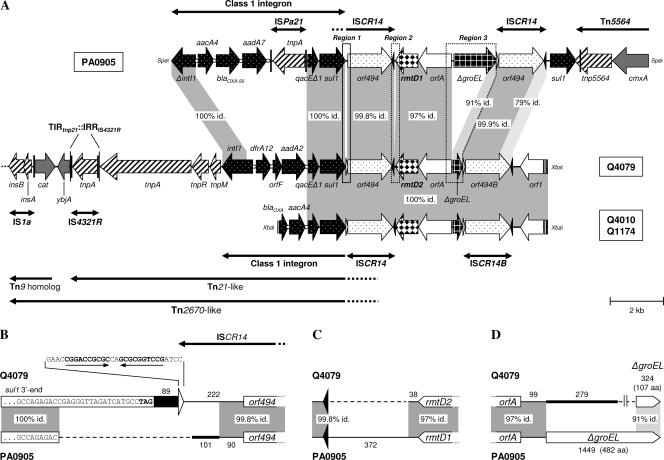

XbaI DNA libraries from E. cloacae Q4010, E. aerogenes Q4079, and C. freundii Q1174 were generated in E. coli TOP10 using the cloning vector pACYC184. The rmtD2-harboring clones were selected with chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml), gentamicin, and kanamycin (4 μg/ml each), and DNA inserts were sequenced using pACYC184-specific and sequence-based primers. The inserts from isolates Q4010 and Q1174 were completely sequenced, while a 19.7-kb partial sequence was obtained from a longer fragment of Q4079. The genetic environments of rmtD2 in these three isolates differed only in the cassette arrays of the class 1 integrons and showed the same ISCR14-bracketed genetic architecture as those surrounding rmtD1 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA0905 and K. pneumoniae R2 from Brazil (5) (Fig. 1 A). However, several key differences between the environments of rmtD1 and rmtD2 were found (Fig. 1B to D). We concluded that the ISCR14-bracketed structures surrounding rmtD1 and rmtD2 are composed of very similar blocks of genes but having different edges. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the second ISCR14 in E. aerogenes Q4079, named herein ISCR14B, is actually a chimera, since the last 337 nucleotides of orf494 and its 256-bp downstream sequence to oriIS showed a maximal identity of 96% with ISCR5B (GenBank accession no. AM849110) but only 79% with ISCR14 (9). Therefore, ISCR14B might have resulted from a recombination between two ISCRs (e.g., ISCR14 and ISCR5B), as has already been reported for ISCR5B, which is itself a chimeric element (9). All of the data strongly suggest that the ISCR14-bracketed region found in the enterobacterial isolates from Argentina and that in P. aeruginosa PA0905 from Brazil were assembled in independent processes through a series of ISCR transposition/homologous recombination events rather than variants derived from a common original structure. This is similar to the proposed model of the ISCR19-bracketed blaOXA-18 structure (12).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the genetic platform of rmtD2. (A) Comparison of the fragments harboring rmtD2 in E. aerogenes Q4079 and C. freundii Q1174 or E. cloacae Q4010 with the genetic environment of rmtD1 in P. aeruginosa PA0905 (5). The gray-shaded areas indicate nucleotide identity. Regions 1, 2, and 3 (framed by dotted lines), which included key differences between both genetic platforms, are depicted in more detail in panels B, C, and D, respectively. The broad horizontal arrows indicate genes and their transcriptional orientations. The attI and attC sites of class 1 integrons are symbolized by open circles. The black and white triangles represent oriIS and terIS, respectively. The thick lines with single or double arrowheads indicate the insertion elements (ISs) and transposons found (black vertical bars show inverted repeats [IRs]). (B) Region 1. A gap (dashed line) was introduced to maximize the alignment, and the numbers (nucleotides) indicate fragment lengths. The last nucleotides of sul1 are shown for each class 1 integron (sequences are not to scale). The black bar and the thick line indicate the sequences downstream to sul1, i.e., the end of the 3′ conserved sequence (3′CS) and a sequence without significant similarity in GenBank, respectively. The white triangle represents the terIS found only in E. aerogenes Q4079, and its sequence is shown (arrows indicate IRs). (C) Region 2. The dashed line and numbers are described for panel B. The black triangles represent oriISs. (D) Region 3. The dashed line and numbers are described for panel B. The thick line indicates a sequence without significant similarity in GenBank. ΔgroEL genes are not to scale, and the number of amino acids (aa) of each putative encoding protein is shown.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a 16S-methylase gene linked to a Tn21-like element (Fig. 1A). Another Tn21-like transposon containing the same class 1 integron (dfrA12-orfF-aadA2) as that found in E. aerogenes Q4079 was previously described in a 65-kb conjugative plasmid from a fecal E. coli isolate (20). Unlike in this plasmid, the Tn21-like element of Q4079 has its terminal inverted repeat at the tnp end (TIRtnp21) disrupted by the insertion of IS4321R (Fig. 1A). However, it was shown that the precise excision of IS4321 can re-create the original TIRtnp21, allowing Tn21 transposition (14). In E. aerogenes Q4079, the Tn21-like element is inserted in the same genetic context as Tn21 in the 94-kb multiresistant plasmid NR1 (R100) of Shigella flexneri, i.e., upstream of the ybjA gene and disrupting a Tn9 homolog (10, 20) (Fig. 1A). Since the Tn21-harboring Tn9 element of NR1 is itself transposable as Tn2670 (10), the location of rmtD2 in a putative Tn2670-like element constitutes another potential means of dissemination. In summary, the finding of rmtD2 in this genetic context suggests that its dissemination could be highly facilitated.

Prevalence of rmtD2.

We observed an rmtD2 prevalence of 0.7% in Enterobacteriaceae. Considering the distribution of species in the collection studied, the prevalence rates of this gene were 9.3% in Enterobacter spp. and 13.3% in Citrobacter spp. To better estimate these rates across a broader time period, an analysis of the WHONET-Argentina database (year 2007, 19,077 enterobacteria) was performed. The total correlation between the presence of rmtD2 and the absence of inhibition zones for both amikacin and gentamicin was used as an indicator of the presence of this gene. As observed in the surveillance collection, the overall prevalence of rmtD2 was low (2.1%) but significantly higher in Enterobacter spp. and Citrobacter spp. than in other enterobacteria (Table 3), suggesting a possible reservoir in these species.

TABLE 3.

Analysis of Enterobacteriaceae from WHONET-Argentina database, 2007

| Group of isolates analyzed (total no.) | % (no.) of isolates with no inhibition zone for AMK or GENa |

|---|---|

| All Enterobacteriaceae (19,077) | 2.1 (403) |

| Enterobacteriaceae minus Enterobacter and Citrobacter spp. (16,906) | 1.2 (211)*† |

| Enterobacter spp. (1,730) | 9.1 (157)* |

| Citrobacter spp. (441) | 7.9 (35)† |

Absence of inhibition zones for both amikacin and gentamicin. Only one isolate per patient was tested. Symbols indicate significant differences (P < 0.0001) by the chi-square test.

In order to establish a continuous surveillance, the National Reference Laboratory had recommended to the WHONET-Argentina hospitals to search for enterobacterial isolates showing an absence of inhibition zones for both amikacin and gentamicin. Twelve strains (4 E. cloacae, 1 Enterobacter agglomerans, 1 C. freundii, 4 K. pneumoniae, and 2 P. mirabilis strains), isolated from January 2008 to April 2009, were selected for molecular characterization. By PCR screening, 10/12 isolates were positive only for rmtD genes. The 2 P. mirabilis isolates were negative for all of the 16S-methylase genes tested and remain under study. By sequencing, rmtD1 was found in 2 K. pneumoniae isolates, while rmtD2 was observed in the remaining 8 isolates.

rmtD2 has been present in Argentina for more than a decade.

The first 16S-methylase producer described in Argentina was a K. pneumoniae strain isolated in 2005 (7). To determine whether this resistance mechanism was present earlier, 153 AmpC-producing enterobacterial strains isolated in 1996 to 1998 from a previous national survey were analyzed (15). Thirteen isolates (1 Enterobacter sp., 8 E. cloacae, 3 C. freundii, and 1 Serratia marcescens isolate) were highly resistant to amikacin and gentamicin (MICs of >256 μg/ml). Four of them (2 E. cloacae, 1 C. freundii, and 1 S. marcescens isolate), selected for 16S-methylase gene characterization, showed rmtD2 only. These results point out the presence of rmtD2 in Enterobacter spp. and C. freundii isolated in the 1990s and strengthen the hypothesis of a reservoir in these species, with a further dissemination to other enterobacteria, such as K. pneumoniae. This presumption indicates that continued surveillance is necessary to monitor the spread of rmtD genes.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences determined here have been assigned GenBank accession numbers HQ401565 (E. aerogenes Q4079), HQ401566 (E. cloacae Q4010), and HQ401567 (C. freundii Q1174).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a start-up grant from the Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion and by the grant Dr. César Milstein, Ministry of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation, Government of Argentina, to R.G.M.

WHONET-Argentina participants include the following: Daniela Ballester, Hospital Piñero; Ana Di Martino, Sanatorio de la Trinidad Mitre; Laura Errecalde, Hospital Fernández; Angela Famiglietti, Hospital de Clínicas; Analía Fernández, Hospital Universitario Fundación Favaloro; Nora Gomez, Hospital Argerich; Horacio Lopardo, Hospital de Pediatría Garrahan; Nora Orellana, FLENI; Adriana Procopio, Hospital de Niños Gutiérrez; Mirta Quinteros, Hospital Muñiz (all in the city of Buenos Aires); Adriana Di Bella, Hospital Posadas, El Palomar; Diana Gómez, Instituto Nacional de Epidemiología Juan Jara, Mar del Plata; Mónica Machain, Hospital Piñeyro, Junín; Andrea Pacha, Hospital San Juan de Dios, La Plata; Susana Palombarani, Hospital Eva Peron, San Martín; Ana Togneri, Hospital Evita, Lanús; Susana Vaylet, Hospital Penna, Bahía Blanca, and Cecilia Vescina, Hospital de Niños Sor Maria Ludovica, La Plata (all in the province of Buenos Aires); Viviana David, Hospital Interzonal San Juan Bautista, and Patricia Valdez, Hospital de Niños Eva Perón, Catamarca; Norma Cech, Hospital 4 de Junio-Ramón Carrillo, Pte. Roque Saenz Peña, and Bettina Irigoyen, Hospital Perrando, Resistencia, Chaco; Omar Daher, Hospital Zonal de Esquel, Chubut; Claudia Aimaretto, Hospital Regional de Villa María; Marina Bottiglieri, Clínica Reina Fabiola; Catalina Culasso, Hospital de Niños de la Santísima Trinidad; Liliana González, Hospital Infantil Municipal; Ana Littvik, Hospital Rawson, and Lidia Wolff, Clínica Privada Vélez Sársfield, city of Córdoba (all in the province of Córdoba); Ana María Pato, Hospital Llano, and Viviana García Saitó, Hospital Pediátrico Juan Pablo II, Corrientes; María Moulins, Hospital Masvernat, Concordia; Humberto Musa, Centro de Microbiología Médica, Paraná, and Francisco Salamone, Hospital San Martín, Paraná, Entre Ríos; Nancy Pereira, Hospital Central de Formosa, and María Vivaldo, Hosp. de la Madre y el Niño, Formosa; Marcelo Toffoli, Hospital de Niños Quintana, and Maria Weibel, Hospital Pablo Soria, Jujuy; Gladys Almada, Hospital Molas, Santa Rosa, and Adriana Pereyra, Hospital Centeno, Gral. Pico, La Pampa; Sonia Flores, Hospital Vera Barros, La Rioja; Lorena Contreras, Hospital Central de Mendoza, and Beatriz García, Hospital Pediátrico Notti, Mendoza; Ana María Miranda, Hospital SAMIC El Dorado, Misiones; María Rosa Núñez, Hospital Castro Rendón, and Herman Sauer, Hospital Heller, Neuquén; Néstor Blázquez, Hospital Carrillo, Bariloche, and Cristina Carranza, Hospital Cipolletti, Río Negro; María Luisa Cacace, Hospital San Vicente de Paul, Orán, and Jorgelina Mulki, Hospital Materno Infantil, Salta; Roberto Navarro, Hospital Rawson, and Nancy Vega, Hospital Marcial Quiroga, San Juan; Ema Fernández, Policlinico Regional J.D. Peron, Villa Mercedes, and Hugo Rigo, Policlínico Central de San Luis, province of San Luis; Wilma Krause, Hospital Regional, Río Gallegos, and Josefina Villegas, Hospital Zonal de Caleta Olivia, Santa Cruz; María Baroni, Hospital de Niños Alassia, and Emilce de los Angeles Méndez, Hospital Cullen, city of Santa Fe; Isabel Bogado, Facultad de Bioquímica, Noemí Borda, Hospital Español, and Adriana Ernst, Hospital de Niños Vilela, Rosario, province of Santa Fe; Ana María Nanni de Fuster, Hospital Regional Ramón Carrillo, Santiago del Estero; Iván Gramundi, Hospital Regional de Ushuaia, and Marcela Vargas, Hospital Regional de Río Grande, Tierra del Fuego; and José Assa, Hospital del Niño Jesús, and Amalia del Valle Amilaga, Hospital Padilla, Tucumán.

We are indebted to D. Faccone, L. Guerriero, and M. Rapoport for technical assistance and to J. Guthrie for a critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to Y. Arakawa, Y. Doi, J. Iredell, M. Galimand, T. Fritsche, and M. Castanheira for supplying the 16S-methylase gene positive controls.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2007. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; seventeenth informational supplement M100-S17. Vol. 27, no. 1. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 2.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2010. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twentieth informational supplement (June 2010 update) M100-S20-U. Vol. 30, no. 15. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 3.Davis, M. A., et al. 2010. Discovery of a gene conferring multiple-aminoglycoside resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2666-2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doi, Y., and Y. Arakawa. 2007. 16S ribosomal RNA methylation: emerging resistance mechanism against aminoglycosides Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:88-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doi, Y., J. M. Adams-Haduch, and D. L. Paterson. 2008. Genetic environment of 16S rRNA methylase gene rmtD. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2270-2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doi, Y., J. Wachino, and Y. Arakawa. 2008. Nomenclature of plasmid-mediated 16S rRNA methylases responsible for panaminoglycoside resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2287-2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fritsche, T. R., M. Castanheira, G. H. Miller, R. N. Jones, and E. S. Armstrong. 2008. Detection of methyltransferases conferring high-level resistance to aminoglycosides in Enterobacteriaceae from Europe, North America, and Latin America. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1843-1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee, K., Y. S. Lim, D. Yong, J. H. Yum, and Y. Chong. 2003. Evaluation of the Hodge test and the imipenem-EDTA double-disk synergy test for differentiating metallo-beta-lactamase-producing isolates of Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4623-4629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li, H., T. R. Walsh, and M. A. Toleman. 2009. Molecular analysis of the sequences surrounding blaOXA-45 reveals acquisition of this gene by Pseudomonas aeruginosa via a novel ISCR element, ISCR5. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1248-1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liebert, C. A., R. M. Hall, and A. O. Summers. 1999. Transposon Tn21, flagship of the floating genome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:507-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livermore, D. M., and N. Woodford. 2006. The ß-lactamase threat in Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter. Trends Microbiol. 14:413-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naas, T., et al. 2008. Genetic structure associated with blaOXA-18, encoding a clavulanic acid-inhibited extended-spectrum oxacillinase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3898-3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pallecchi, L., et al. 2004. Detection of CTX-M-type ß-lactamase genes in fecal Escherichia coli isolates from healthy children in Bolivia and Peru. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4556-4561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Partridge, S. R., and R. M. Hall. 2003. The IS1111 family members IS4321 and IS5075 have subterminal inverted repeats and target the terminal inverted repeats of Tn21 family transposons. J. Bacteriol. 185:6371-6384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasterán, F., et al. 1999. High proportion of extended spectrum ß-lactamases (ESBL) among AMP-C producer enterobacteria in Argentina, abstr. C2-1475. Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 16.Pasterán, F., T. Mendez, M. Rapoport, L. Guerriero, and A. Corso. 2010. Controlling false-positive results obtained with the Hodge and Masuda assays for detection of class A carbapenemase in species of Enterobacteriaceae by incorporating boronic acid. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1323-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pillai, D. R., et al. 2009. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:827-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quiroga, M. P., et al. 2007. Complex class 1 integrons with diverse variable regions, including aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and a novel allele, qnrB10, associated with ISCR1 in clinical enterobacterial isolates from Argentina. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4466-4470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wachino, K., et al. 2007. Novel plasmid-mediated 16S rRNA m1A1408 methyltransferase, NpmA, found in a clinically isolated Escherichia coli strain resistant to structurally diverse aminoglycosides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4401-4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams, L. E., C. Detter, K. Barry, A. Lapidus, and A. O. Summers. 2006. Facile recovery of individual high-molecular-weight, low-copy-number natural plasmids for genomic sequencing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4899-4906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]