Abstract

Children with tuberculosis present with high rates of disseminated disease and tuberculous (TB) meningitis due to poor cell-mediated immunity. Recommended isoniazid doses vary from 5 mg/kg/day to 15 mg/kg/day. Antimicrobial pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies have demonstrated that the ratio of the 0- to 24-h area under the concentration-time curve (AUC0-24) to the MIC best explains isoniazid microbial kill. The AUC0-24/MIC ratio associated with 80% of maximal kill (80% effective concentration [EC80]), considered the optimal effect, is 287.2. Given the pharmacokinetics of isoniazid encountered in children 10 years old or younger, with infants as a special group, and given the differences in penetration of isoniazid into phagocytic cells, epithelial lining fluid, and subarachnoid space during TB meningitis, we performed 10,000 patient Monte Carlo simulations to determine how well isoniazid doses of between 2.5 and 40 mg/kg/day would achieve or exceed the EC80. None of the doses examined achieved the EC80 in ≥90% of children. Doses of 5 mg/kg were universally inferior; doses of 10 to 15 mg/kg/day were adequate only under the very limited circumstances of children who were slow acetylators and had disease limited to pneumonia. Each of the three disease syndromes, acetylation phenotype, and being an infant required different doses to achieve adequate AUC0-24/MIC exposures in an acceptable proportion of children. We conclude that current recommended doses for children are likely suboptimal and that isoniazid doses in children are best individualized based on disease process, age, and acetylation status.

Standard guidelines for isoniazid dosing in children vary greatly. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a regimen of 5 mg/kg daily or 10 mg/kg three times per week in children with tuberculosis (TB) (49). In countries that follow the WHO, the doses administered in the field are actually 6 to 7 mg/kg/day, raising concerns about overdosing (7). Recently, another WHO panel proposed 10 to 15 mg/kg daily (48). The American Thoracic Society/Centers for Diseases Control (ATS/CDC) also recommends 10 to 15 mg/kg daily (2). These recommendations are driven by naive pooled pharmacokinetic data; there are poor population pharmacokinetic data for children. The recommended regimens by and large evolved from those for adults, which are themselves based on peculiarities of treating bacilli in pulmonary cavities. In children ≤10 years old, poor cell-mediated immunity (CMI) leads to disseminated disease, particularly to the meninges, with disseminated TB accounting for a fifth to half of all cases of TB, especially in areas where HIV is endemic (9, 27, 34). Pulmonary disease, when it occurs, is cavitary in only 6% of cases (49). This means that in this age group, indices of isoniazid penetration into meninges, phagocytes, and epithelial lining fluid (ELF) are important determinants of outcome.

There have been several attempts to design new isoniazid doses for children. One attempt identified a daily isoniazid dose that would achieve a peak serum concentration (Cmax) of 3 to 5 mg/liter, which is considered optimal (38). Using such an approach, it was demonstrated that the optimal daily dose that would achieve such a Cmax in children is 8 to 12 mg/kg (29). This was an important step in designing optimal doses, because it gave a clearly defined drug concentration target for clinicians to aim for. In order to improve on this, three other factors vital in determining pathogen response to drug concentration need consideration. The first is the MIC for the isolate. It is a general principle of antimicrobial pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) that the higher the MIC, the poorer the response (1, 4, 10, 32, 42, 43). Thus, the variability of MICs is an important determinant of response. Therefore, drug concentrations should be indexed to MIC. Second, the optimal target exposure should be prospectively derived and defined from a full exposure-effect curve of the PK/PD index linked to effect. For isoniazid, the PK/PD index associated with optimal kill is unequivocally the ratio of the 0- to 24-h area under the concentration-time curve (AUC0-24) to the MIC, based on results from four independent studies (3, 17, 21, 35). The isoniazid AUC/MIC exposure associated with maximal or near-maximal kill of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the best target to aim for in therapy. A third important issue is that of drug penetration to reach the pathogen; to state the obvious, optimal drug exposures are relevant only if they are achieved at the site of infection. In children with TB these anatomic sites are the subarachnoid space, phagolysosomes inside phagocytes, and pulmonary lesions.

Clinical trial simulations that utilize Monte Carlo methods have been performed for identification of optimal dose and susceptibility breakpoints in adults with TB (13-18, 35). These simulations are stochastic rather than deterministic and take into account both pharmacokinetic and MIC variability as well as drug penetration to the site of infection. The central step is the ability to achieve the PK/PD exposures associated with maximum microbial kill as prospectively identified in animal TB models or in the hollow-fiber PK/PD model of TB. The latter model has been called the “glass mouse.” Recently Laer et al. called for simulations to identify optimal doses for the pediatric patient, the “in silico child” (25). In this study we used Monte Carlo simulations to identify optimal doses in children with TB who are 10 years old or younger, with target isoniazid exposure derived from our isoniazid PK/PD studies in the “glass mouse.”

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isoniazid PK/PD targets.

Isoniazid PK/PD exposure effect curves derived in the hollow-fiber, guinea pig, and mouse models have demonstrated similar inhibitory sigmoid Emax model parameters (17, 21, 35). The hollow-fiber PK/PD model of TB has no immune system, making it a particularly good model for deriving exposures for disseminated TB in children under 10 years old, in whom CMI is expected to be poor, especially in the context of HIV coinfection (34). In that model the isoniazid AUC0-24/MIC ratio that mediates 80% of maximal kill of M. tuberculosis (80% effective concentration [EC80]) (considered the optimal effect) was 287.2 (17).

Isoniazid population pharmacokinetics in children less than 10 years old.

There are no published population pharmacokinetic data for isoniazid in children. However, a study by Rey and colleagues in which isoniazid peak concentration, systemic clearance (SCL), and volume of distribution (V) were identified for each of 33 children and listed by age and acetylation status (41) was used to construct median parameter estimates and variance for children ≤10 years old. Since Schaaf et al. demonstrated that the elimination rate constant increases with decreasing age in children (45), we also explored the effect of age on SCL and V in the results of Rey et al. However, the absorption constant (Ka) could not be calculated based on any of the published data, and we set it at 4.2 ± 5.64 h−1 for fast acetylators and 6.6 ± 7.49 h−1 for slow acetylators, similar to the values for adults (39). The effect of weight as an independent variable could not be assessed.

Disease pattern and isoniazid penetration into infected sites.

Because of the problem of system hysteresis, multiple simultaneous samples of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma from children with TB meningitis are needed. Donald et al. sampled 38 children age 0.3 to 8.6 years multiple times and reported means (± standard deviations [SD]) of simultaneous CSF and plasma concentrations at seven time points (8). We analyzed these concentrations in order to compare the shapes of the isoniazid concentration-time curves for plasma and CSF. Isoniazid CSF and plasma concentrations at seven time points were analyzed with the ADAPT II program (6), with plasma data examined using a one-compartment model with first-order absorption and CSF data examined using a one-compartment model and first-order absorption with a lag. From these, the ratio of isoniazid AUC0-24 in CSF to that in plasma was then identified and utilized for subsequent simulations. On the other hand, there are no data on isoniazid epithelial lining fluid (ELF)-to-plasma ratio in children, but a ratio of 2 has been calculated for adults and was used in this study (5, 22). Intracellular M. tuberculosis were assumed to be within neutrophils and macrophages (11). Based on drug penetration at four or five sampling time points, the isoniazid macrophage/plasma concentration ratio was calculated as 0.74 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.45 to 1.03), while the neutrophil/plasma ratio was 1.26 (95% CI, 0.91 to 1.60) (5, 19, 40). Thus, for intracellular bacilli, isoniazid AUC0-24 exposures were assumed to be equal to those in the central compartment. The protein binding of isoniazid is only 1 to 10%, and therefore protein binding in ELF and CSF is expected to be negligible (23, 37).

Monte Carlo simulations.

Clinical trial simulations were performed in silico for 10,000 children who each received a dose of isoniazid for which we determined the probability of achieving or exceeding the AUC0-24/MIC ratio of 287.2 in either (i) phagocytic cells, (ii) CSF, or (iii) ELF, by use of the Monte Carlo method (30, 31). The experimental doses examined were 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 15, 20, and 40 mg/kg/day. The optimal dose was the minimum dose that achieved the EC80 in ≥90% of children. Isoniazid pharmacokinetic parameter estimates and their variances (i.e., domain of inputs), based on our calculations from the data of Rey et al. (41), were entered as prior data in subroutine PRIOR of the ADAPT II program (6). After input of a random-number generator, the program output is a distribution of 10,000 SCLs. It is known that 88% of variability in the isoniazid SCL is due to polymorphisms of the arylamine N-acetyltransferase 2 (nat-2) enzymes encoded by NAT-2*4 alleles (24). Therefore, simulations were performed separately for fast and slow acetylators. Both normal and log-normal distributions were examined, and the final distribution was chosen on the basis of fidelity of recapitulating the original pharmacokinetic data. For a drug such as isoniazid, whose absorption is rapid and whose bioavailability approaches 100%, the AUC0-24 is easily computed from the dose for each SCL value. At each MIC, AUC0-24/MIC values that are ≥EC80 are identified and the target attainment probability (TAP) is summarized, based on proportions of isolates at each MIC in the distribution. For the purposes of this study, we utilized the MIC distribution for 1,217 clinical M. tuberculosis isolates from Japan, the largest known published set (50). However, it should be noted that for each locale, the final TAP depends on the MIC distribution unique to that place. As an example, we explored the TAP in fast-acetylator children in a hypothetical locale where bacilli are more susceptible to isoniazid by shifting the Japanese MIC distribution two tube dilutions lower.

Software and hardware.

The ADAPT II program was developed by D'Argenio and Schumitzky by use of NIH funding and is therefore free software that can be downloaded from anywhere (6). Simulations utilizing this software were performed on a PC. For better graphing, some of the ADAPT II results were imported into GraphPad Prism 5 on the same PC.

RESULTS

Pharmacokinetics.

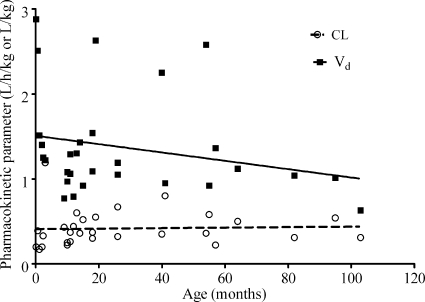

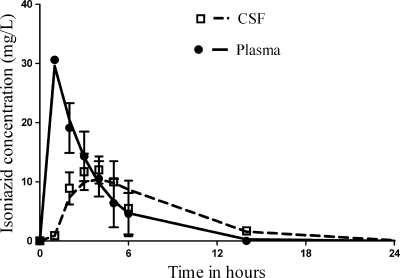

The full pharmacokinetic parameters identified in the children are shown in Table 1. We found no overall correlation between age and either V or SCL when age was computed as a continuous variable (Fig. 1). However, when age was computed as a categorical variable for infants, who were defined as children 1 year old or younger versus those 1 to 10 years old, slow-acetylator infants had an SCL different from those of others (Table 1). In regard to CSF pharmacokinetics, Fig. 2 is based on our population pharmacokinetic modeling and depicts concentrations observed in the 27 children with TB meningitis who were treated with 20 mg/kg isoniazid, reported by Donald et al. (8), superimposed on the 24-h concentration-time profile based on our population pharmacokinetic modeling with their data. These data, however, are based on the report which had averaged concentrations for slow- and fast-acetylator children, so that only parameter estimates could be calculated. However, these data enabled us to calculate the isoniazid CSF/plasma AUC0-24 ratio, which was 0.80. All these pharmacokinetic data are presented in Table 1 and were used in subsequent Monte Carlo simulations.

TABLE 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters and assumptions used in Monte Carlo simulations

| Parameter | Value (mean ±SD) in: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fast acetylators | Slow-acetylator infants | Slow acetylators 1 to 10 yr old | |

| Clearance (liters h−1 kg−1) | 0.54 ± 0.24 | 0.24 ± 0.07 | 0.37 ± 0.08 |

| V (liters kg−1) | 1.13 ± 0.45 | 1.46 ± 0.66 | 1.72 ± 0.67 |

| Ka (h−1) | 4.2 ± 5.64 | 6.6 ± 7.49 | 6.6 ± 7.49 |

| CSF/plasma AUC0-24 ratio | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| ELF/plasma isoniazid ratio | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Phagocyte/plasma isoniazid ratio | 1 | 1 | 1 |

FIG. 1.

Relationship between pharmacokinetic parameter and age. The correlations with age as a continuous variable were r = 0.04 and a slope of 0.0003 ± 0.0014 for clearance and r = 0.24 and a slope of −0.0049 ± 0.0039 for V.

FIG. 2.

Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of isoniazid, showing the concentrations observed by Donald et al. (8) as well as our modeled concentration-time profiles, including standard deviations.

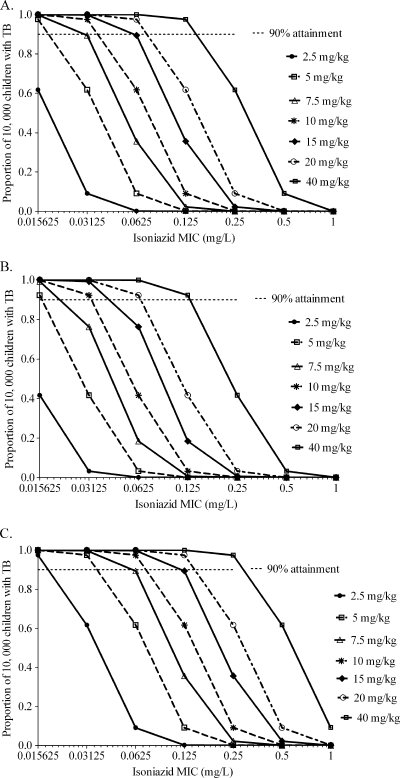

Monte Carlo simulations for children who are fast acetylators.

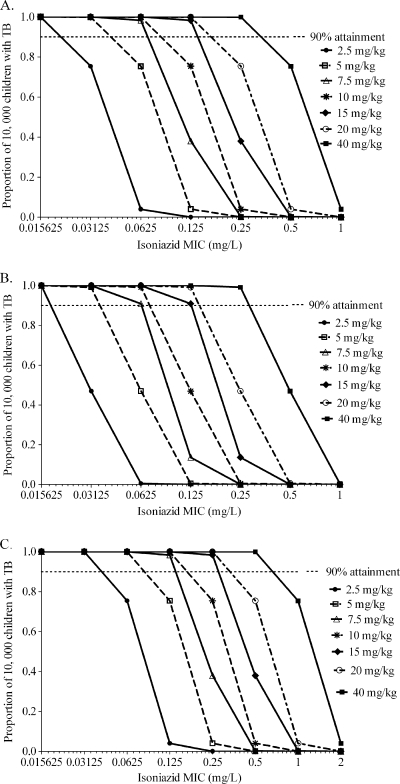

The probabilities of each of the several doses achieving or exceeding EC80 in fast acetylators are shown in Fig. 3. Whether considering the treatment of disseminated TB with no meningitis (Fig. 3A), TB meningitis (Fig. 3B), or even pneumonia (Fig. 3C), doses of 2.5 to 10 mg/kg performed poorly within an MIC range for “susceptible” isolates. Indeed, for TB meningitis even doses of 15 to 20 mg/kg performed poorly in this group of children. An important finding, shown in Fig. 3A to C, is that different isoniazid doses perform differently according to site of infection, and therefore by disease syndrome, so that doses should be individualized by the type of TB that a child has.

FIG. 3.

Performance of different isoniazid doses in children who are fast acetylators. The probabilities of achieving an isoniazid AUC0-24/MIC of 287.2 in children with disseminated TB with no meningitis (A), TB meningitis (B), and pneumonia (C) are shown.

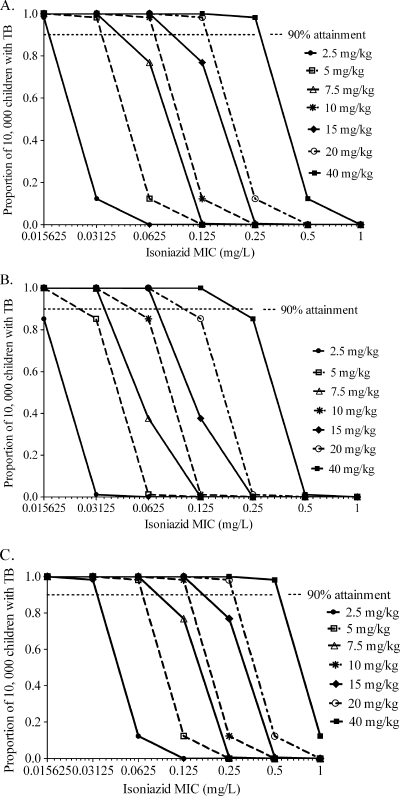

Monte Carlo simulations for slow-acetylator children between 1 and 10 years old.

Among children who were slow acetylators, isoniazid doses of 2.5 to 5 mg/kg performed poorly whether for disseminated TB, TB meningitis, or pneumonia (Fig. 4) caused by susceptible M. tuberculosis isolates. For TB meningitis, doses of up to 7.5 mg/kg were insufficient among a wide range of MICs (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Performance of different isoniazid doses in children 1 to 10 years old who are slow acetylators. The probabilities of achieving an isoniazid AUC0-24/MIC of 287.2 in children with disseminated TB with no meningitis (A), TB meningitis (B), and pneumonia (C) are shown.

Monte Carlo simulations for infants who are slow acetylators.

Slow-acetylator infants had the lowest SCL, which means that relatively high AUCs could be achieved in this group (Fig. 5). Despite that advantage, doses of 5 to 7.5 mg/kg/day (Fig. 5B) were inadequate in infants with TB meningitis. Doses of up to 5 mg/kg were also inadequate in infants with disseminated disease (Fig. 5A), which means that 5 mg/kg would be useful only at low MICs and then only in infants with pulmonary TB not complicated by dissemination.

FIG. 5.

Performance of different isoniazid doses in infants who are slow acetylators. The probabilities of achieving an isoniazid AUC0-24/MIC of 287.2 in children with disseminated TB with no meningitis (A), TB meningitis (B), and pneumonia (C) are shown.

TAP.

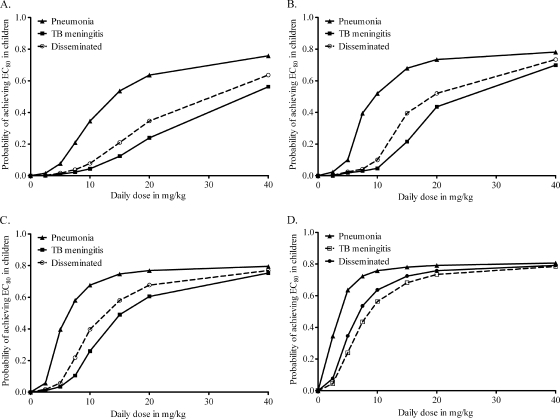

For each group of children, the overall performance of each dose, the target attainment probability (TAP), was calculated based on MICs from Japan (50); the TAPs are shown in Fig. 6. No dose of between 2.5 and 40 mg/kg/day achieved an EC80 in ≥90% of children. Doses of 5 mg/kg performed poorly across the board. Among fast acetylators, the performance of all doses, including WHO- and ATS/CDC-recommended doses, was extremely poor (Fig. 6A). Indeed, no dose achieved the EC80 in ≥90% of the children (Fig. 6A to C). Since the poor performance is driven not just by pharmacokinetics (and variability) but also by the MIC distribution, we examined a scenario for fast acetylators in which the MIC distribution curve reported by Yamane et al. (50) was shifted by two dilutions to the left, so that the median would shift from 0.03 mg/liter to 0.0078 mg/liter (i.e., making it really more susceptible). As shown in Fig. 6D, the TAP was somewhat better; however, 2.5 to 5 mg/kg still performed poorly, and 10 mg/kg was still inadequate for meningitis and disseminated TB.

FIG. 6.

Relationship between dose and target attainment probability. The results are for 10,000 children who are fast acetylators (A), slow acetylators and between 1 and 10 years old (B), slow acetylator infants (C), or fast acetylators with M. tuberculosis highly susceptible to isoniazid (D).

DISCUSSION

In the treatment of latent TB, isoniazid is often administered as a single agent. Even though isoniazid is dosed in combination with rifampin and pyrazinamide for the treatment of active TB, it is nevertheless important to optimize the dose of this critical drug. Indeed, in diseases such as TB meningitis, where rifampin penetration into CSF/plasma is only 0.05 to 0.1 for a drug with 80 to 98% protein binding so that effective CSF exposures are only 1/1,000 to 2/100 of those in serum (26, 44, 47) and the efficacy of pyrazinamide is questionable given that the CSF pH is >7.0 and the drug is effective only at pHs below that (28, 51), the isoniazid effect is expected to play the predominant role in the combination. Clearly, from an efficacy standpoint the doses recommended by the WHO and the ATS/CDC are too low to achieve optimal exposures in many circumstances.

A second important point is the obvious need to individualize isoniazid doses in children. Despite the egalitarian desire for “standardized” therapy, in reality there is no “average” or “standard” child. They are as varied from each other as planets are from one another. In fact, variability is the point of evolution. Pharmacokinetic variability is one such manifestation, likely arising due to differential exposure of xenobiotic enzymes to plant chemicals in human ancestors (12). It is useful to assume that among the 2.2 billion children currently alive on earth, there will be 2.2 billion different concentration-time curves. Therefore, it is not a surprise that isoniazid pharmacokinetic parameters have a wide distribution, which means that a fixed dose will produce different AUC0-24 values in different children. Of course, in localities where fast acetylation is the overwhelmingly predominant phenotype, such as in countries of East Asia, the first doses administered would be those for fast acetylators, and the doses would be altered a few days later after establishment of the slow-acetylator phenotype by any one of several methods. The second factor to enter the decision on individualization of the isoniazid dose is the disease process, which is readily available from history and physical examination of the child. As an example, the small proportion of children in whom TB is unequivocally limited to a pneumonic process would get lower doses, while those with disseminated TB and TB meningitis would get higher doses, based on Fig. 6. The third important factor in individualizing the dose is the age of the child, so that there would also be a different dose for slow-acetylator infants.

Another important aspect arising from our study concerns the need for good population pharmacokinetic data. While we made use of line-listed SCL and V values published by others in the past, perhaps the greatest gap in knowledge that militates against optimal dosing for children is the lack of compartmental and population pharmacokinetics derived from a large and diverse enough population of children. This is indeed the major limitation our current paper. Studies should examine children at different ages as well as with differences in nutritional status, presence of AIDS, concomitant antiretroviral therapy, and SNPs of genes encoding xenobiotic metabolism enzymes as covariates of population pharmacokinetic parameters. In this context, our current studies represent merely a first step. In regard to isoniazid CSF parameters and drug penetration, the only other study to sample the CSF multiple times that we could find was with adults; nevertheless, the elimination constants and CSF/plasma penetration ratios in that study were similar to our calculations (46). However, clearly both studies were small, and larger studies are needed. With better population pharmacokinetic parameter estimates from such studies, even more precise optimal doses will be identified and individualization of doses further improved beyond our current attempts.

Finally, while microbiological diagnosis is often difficult in children, there is nevertheless a great need to isolate enough strains of M. tuberculosis from children in many different countries so that true MIC distributions can be established. Given that evolution is also a pressure on M. tuberculosis, there is expected to be a genetically determined wide variability in MIC distribution from region to region. The current practice of categorizing isolates only as either “resistant” or “susceptible” based on epidemiological cutoff methods is problematic; the breakpoints themselves are questionable based on PK/PD grounds (15). While the dichotomous interpretation should be continued, it would be more informative if the actual MICs were also known.

There are other limitations to our proposals. It is likely that with increased dosing there will be increased toxicity. It is currently unclear which isoniazid pharmacokinetic parameter best predicts the development of toxicity. The increased isoniazid hepatotoxicity in adult TB patients who carry the NAT2*6A haplotype (SNPs C282T and G590A), which is associated with slow acetylation, and the protection by the NAT2*4 haplotype, which is associated with fast acetylation (20), suggest that either the AUC0-24 or the time that concentration persists above a threshold is a predictor of toxicity. With studies to better understand the isoniazid toxicodynamics, regimens that optimize efficacy while reducing toxicity in the same way as suggested for pyrazinamide can be designed (35). A second important limitation may be encountered with individualized dosing in resource-limited countries, especially the determination of acetylation status. A solution may be a 3-h plasma sample after a few doses or performance of one of the surrogate urine tests for acetylation phenotype sent out as a routine test to a central laboratory or hospital in the country. Even if such results take a few weeks to come back, they could nevertheless be used to adjust the dose downward if the child is a slow acetylator. Faster and inexpensive colorimetric point-of-care tests could also be a focus for further research. Nevertheless, while resource limitations may limit the capacity of some pediatricians to individualize doses, the rational approach would be to attempt this as far as is practicable, since this is likely to lead to better patient outcomes (33). Finally, we did not attempt to design doses that could suppress resistance. Those would be higher than doses for optimal microbial kill and likely beyond the range that is clinically useful.

In summary, we examined several doses of isoniazid in children ≤10 years old in Monte Carlo simulations. Currently recommended doses are not expected to achieve optimal exposures in children, and higher doses are needed. In addition, doses should be individualized by disease process, age, and acetylation status. The precision of identifying optimal doses would be improved by further studies that establish population pharmacokinetics of anti-TB drugs in children as well as the drug MIC variability in clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis from pediatric patients.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambrose, P. G., et al. 2007. Pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of antimicrobial therapy: it's not just for mice anymore. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:79-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumberg, H. M., et al. 2003. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America: treatment of tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 167:603-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budha, N. R., R. B. Lee, J. G. Hurdle, R. E. Lee, and B. Meibohm. 2009. A simple in vitro PK/PD model system to determine time-kill curves of drugs against Mycobacteria. Tuberculosis (Edinb.). 89:378-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clancy, C. J., V. L. Yu, A. J. Morris, D. R. Snydman, and M. H. Nguyen. 2005. Fluconazole MIC and the fluconazole dose/MIC ratio correlate with therapeutic response among patients with candidemia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3171-3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conte, J. E., Jr., et al. 2002. Effects of gender, AIDS, and acetylator status on intrapulmonary concentrations of isoniazid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2358-2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Argenio, D. Z., and A. Schumitzky. 1997. ADAPT II. A program for simulation, identification, and optimal experimental design. User manual. Biomedical Simulations Resource. University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

- 7.Diop, A. H., G. Gakiria, S. B. Pande, P. Malla, and H. L. Rieder. 2002. Dosages of anti-tuberculosis medications in the national tuberculosis programs of Kenya, Nepal, and Senegal. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 6:215-221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donald, P. R., W. L. Gent, H. I. Seifart, J. H. Lamprecht, and D. P. Parkin. 1992. Cerebrospinal fluid isoniazid concentrations in children with tuberculous meningitis: the influence of dosage and acetylation status. Pediatrics 89:247-250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donald, P. R., H. S. Schaaf, and J. F. Schoeman. 2005. Tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis: the Rich focus revisited. J. Infect. 50:193-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drusano, G. L., D. E. Johnson, M. Rosen, and H. C. Standiford. 1993. Pharmacodynamics of a fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agent in a neutropenic rat model of Pseudomonas sepsis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:483-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eum, S. Y., et al. 2010. Neutrophils are the predominant infected phagocytic cells in the airways of patients with active pulmonary TB. Chest 137:122-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez, F. J., and D. W. Nebert. 1990. Evolution of the P450 gene superfamily: animal-plant ‘warfare’, molecular drive and human genetic differences in drug oxidation. Trends Genet. 6:182-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goutelle, S., et al. 2009. Population modeling and Monte Carlo simulation study of the pharmacokinetics and antituberculosis pharmacodynamics of rifampin in lungs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2974-2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gumbo, T. 2008. Integrating pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and pharmacogenomics to predict outcomes in antibacterial therapy. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 11:32-42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gumbo, T. 2010. New susceptibility breakpoints for first-line antituberculosis drugs based on antimicrobial pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic science and population pharmacokinetic variability. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1484-1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gumbo, T., et al. 2004. Selection of a moxifloxacin dose that suppresses drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, by use of an in vitro pharmacodynamic infection model and mathematical modeling. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1642-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gumbo, T., et al. 2007. Isoniazid bactericidal activity and resistance emergence: integrating pharmacodynamics and pharmacogenomics to predict efficacy in different ethnic populations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2329-2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gumbo, T., C. S. Siyambalapitiyage Dona, C. Meek, and R. Leff. 2009. Pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of pyrazinamide in a novel in vitro model of tuberculosis for sterilizing effect: a paradigm for faster assessment of new antituberculosis drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3197-3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hand, W. L., R. W. Corwin, T. H. Steinberg, and G. D. Grossman. 1984. Uptake of antibiotics by human alveolar macrophages. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 129:933-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higuchi, N., et al. 2007. NAT2 6A, a haplotype of the N-acetyltransferase 2 gene, is an important biomarker for risk of anti-tuberculosis drug-induced hepatotoxicity in Japanese patients with tuberculosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 13:6003-6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayaram, R., et al. 2004. Isoniazid pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics in an aerosol infection model of tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2951-2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katiyar, S. K., S. Bihari, and S. Prakash. 2008. Low-dose inhaled versus standard dose oral form of anti-tubercular drugs: concentrations in bronchial epithelial lining fluid, alveolar macrophage and serum. J. Postgrad. Med. 54:245-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiem, S., and J. J. Schentag. 2008. Interpretation of antibiotic concentration ratios measured in epithelial lining fluid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:24-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinzig-Schippers, M., et al. 2005. Should we use N-acetyltransferase type 2 genotyping to personalize isoniazid doses? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1733-1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laer, S., J. S. Barrett, and B. Meibohm. 2009. The in silico child: using simulation to guide pediatric drug development and manage pediatric pharmacotherapy. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 49:889-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahajan, M., et al. 1997. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of rifampicin at two dose levels in children with tuberculous meningitis. J. Commun. Dis. 29:269-274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maltezou, H. C., P. Spyridis, and D. A. Kafetzis. 2000. Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis in children. Arch. Dis. Child 83:342-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDermott, W., and R. Tompsett. 1954. Activation of pyrazinamide and nicotinamide in acidic environments in vitro. Am. Rev. Tuberc. 70:748-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McIlleron, H., et al. 2009. Isoniazid plasma concentrations in a cohort of South African children with tuberculosis: implications for international pediatric dosing guidelines. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1547-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Metropolis, N. 1987. The begining of the Monte Carlo method. Los Alamos Sci. Spec. Issue 15:125-130. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Metropolis, N., and S. Ulam. 1949. The Monte Carlo method. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 44:335-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moise-Broder, P. A., et al. 2004. Accessory gene regulator group II polymorphism in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is predictive of failure of vancomycin therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1700-1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neely, M., and R. Jelliffe. 2010. Practical, individualized dosing: 21st century therapeutics and the clinical pharmacometrician. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 50:842-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newton, S. M., A. J. Brent, S. Anderson, E. Whittaker, and B. Kampmann. 2008. Paediatric tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 8:498-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pasipanodya, J. G., and T. Gumbo. 2010. Clinical and toxicodynamic evidence that high dose pyrazinamide is not more hepatotoxic than current low doses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2847-2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pasipanodya, J., and T. Gumbo. 2010. An oracle: antituberculosis pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamics, clinical correlation, and clinical trial simulations to predict the future. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:24-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peloquin, C. A. 1991. Antituberculosis drugs: pharmacokinetics, p. 89-122. In L. B. Heifets (ed.), Drug susceptibility in chemotherapy of mycobacterial infections. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 38.Peloquin, C. A. 2002. Therapeutic drug monitoring in the treatment of tuberculosis. Drugs 62:2169-2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peloquin, C. A., et al. 1997. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2670-2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prokesch, R. C., and W. L. Hand. 1982. Antibiotic entry into human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 21:373-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rey, E., et al. 2001. Isoniazid pharmacokinetics in children according to acetylator phenotype. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 15:355-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodriguez-Tudela, J. L., et al. 2007. Correlation of the MIC and dose/MIC ratio of fluconazole to the therapeutic response of patients with mucosal candidiasis and candidemia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3599-3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakoulas, G., et al. 2004. Relationship of MIC and bactericidal activity to efficacy of vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2398-2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sauermann, R., R. Schwameis, M. Fille, M. L. Ligios, and M. Zeitlinger. 2008. Antimicrobial activity of cefepime and rifampicin in cerebrospinal fluid in vitro. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:1057-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schaaf, H. S., et al. 2005. Isoniazid pharmacokinetics in children treated for respiratory tuberculosis. Arch. Dis. Child 90:614-618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shin, S. G., et al. 1990. Kinetics of isoniazid transfer into cerebrospinal fluid in patients with tuberculous meningitis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 5:39-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woo, J., et al. 1996. In vitro protein binding characteristics of isoniazid, rifampicin, and pyrazinamide to whole plasma, albumin, and alpha-1-acid glycoprotein. Clin. Biochem. 29:175-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Health Organization. 2006. Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children. Childhood TB subgroup, Stop TB Partnership. WHO/HTM/TB/2006.371. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 49.World Health Organization. 2008. Report of the meeting on TB medicines for children. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 50.Yamane, N., et al. 1999. Multicenter evaluation of broth microdilution test, BrothMIC MTB, to determine minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antimicrobial agents for Mycobacterium tuberculosis: evaluation of interlaboratory precision and interpretive compatibility with agar proportion method. Jpn. J. Clin. Pathol. 47:754-766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, Y., A. Scorpio, H. Nikaido, and Z. Sun. 1999. Role of acid pH and deficient efflux of pyrazinoic acid in unique susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to pyrazinamide. J. Bacteriol. 181:2044-2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]