Abstract

Polyphosphate [poly(P)] has antibacterial activity against various Gram-positive bacteria. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria are generally resistant to poly(P). Here, we describe the antibacterial characterization of poly(P) against a Gram-negative periodontopathogen, Porphyromonas gingivalis. The MICs of pyrophosphate (Na4P2O7) and all poly(P) (Nan + 2PnO3n + 1; n = 3 to 75) tested for the bacterium by the agar dilution method were 0.24% and 0.06%, respectively. Orthophosphate (Na2HPO4) failed to inhibit bacterial growth. Poly-P75 was chosen for further study. In liquid medium, 0.03% poly-P75 was bactericidal against P. gingivalis irrespective of the growth phase and inoculum size, ranging from 105 to109 cells/ml. UV-visible spectra of the pigments from P. gingivalis grown on blood agar with or without poly-P75 showed that poly-P75 reduced the formation of μ-oxo bisheme by the bacterium. Poly-P75 increased hemin accumulation on the P. gingivalis surface and decreased energy-driven uptake of hemin by the bacterium. The expression of the genes encoding hemagglutinins, gingipains, hemin uptake loci, chromosome replication, and energy production was downregulated, while that of the genes related to iron storage and oxidative stress was upregulated by poly-P75. The transmission electron microscope showed morphologically atypical cells with electron-dense granules and condensed nucleoid in the cytoplasm. Collectively, poly(P) is bactericidal against P. gingivalis, in which hemin/heme utilization is disturbed and oxidative stress is increased by poly(P).

Inorganic polyphosphate [poly(P)] is a ubiquitous compound found in bacteria, fungi, algae, plants, and animals. The poly(P) found in the organisms is a chain of a few or many hundreds of phosphate (Pi) residues linked by high-energy phosphoanhydride. It performs varied functions in bacteria: it can serve as an ATP source and substitute, it is a strong chelator of metal ions and thus can regulate the levels of the ions in the cells, it is a channel for DNA entry, and it is a regulator that contributes to bacterial resistance and survival under stress and stringent conditions (18). Therefore, intracellular poly(P) is considered a virulence factor of microorganisms.

In contrast, exogenous poly(P) has attracted considerable attention as an antimicrobial agent, since it can prevent spoilage of food (29, 32), and it is listed as a GRAS (generally recognized as safe) food additive by the FDA. Poly(P) inhibits the growth of various Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus (14, 17, 22, 35, 52), Listeria monocytogenes (37, 52), Sarcina lutea (35), Bacillus cereus, and Lactobacillus, and of fungi, such as Aspergillus flavus (17, 28). Concerning oral bacteria, mutans streptococci were first found to be inhibited by condensed phosphate, resulting in a decrease of plaque formation and dental caries (5, 39). The ability of poly(P) to chelate divalent cations is regarded as relevant to the antibacterial effects of poly(P), contributing to cell division inhibition and loss of cell wall integrity (17, 24, 28, 35). Therefore, relatively little attention has been directed toward the effect of poly(P) on Gram-negative bacteria, in which the divalent cation is considered less important for membrane stability. In fact, Gram-negative bacteria are generally more resistant than Gram-positive organisms to poly(P); large numbers of Gram-negative bacteria, including Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, are capable of growing in higher concentrations, even up to 10%, of poly(P) (17, 34, 35).

Poly(P) does not generally exert any adverse effect on the body when used locally and orally within the range of MICs determined for various bacteria (20). In addition, poly(P) can stimulate bone formation (11). Thus, poly(P) seems to be a promising substance for treatment of periodontal diseases, promoting bone regeneration. Before clinical application of poly(P) as a controlling agent for periodontal diseases can begin, the effect of poly(P) on periodontopathogens must be defined.

Porphyromonas gingivalis is a Gram-negative, black-pigmented anaerobe associated with several periodontal diseases (9). Iron is a nutrient that is indispensable for the growth of almost all living organisms, including P. gingivalis, and plays a crucial role in the establishment and progression of infection (40). P. gingivalis lacks members of the protoporphyrin IX synthetic pathway but requires hemin (Fe3+-protoporphyrin IX, also known as heme and Fe2+-protoporphyrin IX, depending upon the oxidation state of the iron atom in the center of the molecule) as a cofactor for fumarate reductase and cytochromes, so the bacterium must acquire the nutrient from the environment (1, 6). P. gingivalis derives hemin via hemagglutination, hemolysis, and proteolysis of hemoglobin (4, 42) and stores hemin on the cell surface in μ-oxo dimeric form {μ-oxo bisheme, [Fe(III)PPIX2]O}. This surface-bound μ-oxo bisheme serves not only as a scavenger of hemin, which in high concentrations (10 to 20 μg/ml) has been shown to have antibacterial effects on P. gingivalis, but also binds free oxygen and thereby reduces hemin-mediated oxygen radical cell damage, as well as protecting from reactive oxidants generated by neutrophils (25, 44). The P. gingivalis genome encodes a family of hemagglutinins (HagA, HagB, and HagC) and gingipains (Arg-specific gingipains A and B [RgpA and RgpB] and Lys-specific gingipain [Kgp]) that play crucial roles in the hemin acquisition process (7, 15, 19). The surface-accumulated hemin is transported into a bacterial cell to be utilized and serves as a source of iron under iron-depleted conditions (38). Since hemin is too large to diffuse freely through the bacterial membranes, P. gingivalis requires transport of hemin across two membranes by a process that requires energy (41). Three multigenic clusters have been detected in the genome of P. gingivalis W83, encoding proteins thought to be involved in hemin uptake (26): IhtABCDE (iron-heme transport), Tlr-htrABCD (hemin uptake), and HmuYRSTUV (hemin uptake).

In a preliminary study, we observed that the pellet of P. gingivalis W83 cells grown in brucella broth supplemented with hemin appeared darker in the presence of poly(P), likely due to the P. gingivalis cell surface binding more hemin (unpublished data). Hence, we hypothesized that poly(P) may affect the hemin utilization of P. gingivalis. Here, we present antimicrobial activity of poly(P) against P. gingivalis, disturbing hemin/heme utilization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Orthophosphate (Pi; Na2HPO4), pyrophosphate (PPi; Na4P2O7), and poly(P), (Nan + 2PnO3n + 1; n = the number of phosphorus atoms in the chain) with different linear phosphorus (Pi) chain lengths (3 to 75) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Calgon (Sigma), a cyclic polyphosphate (sodium hexametaphosphate, NanPnO3n; n = 12 to 13), was also used. These phosphates were dissolved in water to 10% (wt/vol), sterilized using a 0.22-μm filter, and stored at −20°C until they were used. Stock solutions of hemin (Sigma) were prepared in 0.02 N NaOH the same day that they were used. Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) (Sigma) was dissolved in 20% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and used as an inhibitor of energy-driven transport activities (3). Deferoxamine mesylate (DFO) (Novartis Pharma Stein AG, Stein, Switzerland), an iron chelator, was dissolved in water to 20% (wt/vol).

Antimicrobial assays.

The MIC of poly(P) for P. gingivalis W83 (kindly supplied by Koji Nakayama, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences) was obtained by the agar dilution method according to CLSI guidelines (8). Briefly, 2-fold serial dilutions of Pi, PPi, and poly(P) with various chain lengths (3 to 75) were prepared and added to brucella agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) containing 5% laked sheep blood, 5 μg/ml of hemin, and 1 μg/ml of vitamin K1. The final concentrations of Pi, PPi, and poly(P) ranged from 0.015% to 0.96% (wt/vol). The agar plates were inoculated with an inoculum of 105 CFU/spot and incubated at 37°C for 48 h anaerobically (85% N2, 10% H2, and 5% CO2). The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration that inhibited bacterial growth on the plate.

Time-kill experiments were performed in brucella broth containing hemin and vitamin K1. Poly(P) with a chain length of 75 (poly-P75) was tested at concentrations of 1/4 to 4 MIC. Aliquots were removed from the cultures at 0, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h, and viable cells were enumerated by plating them on blood agar. In order to assess the effects of inoculum density and growth phase on the killing effect of poly-P75, cells of P. gingivalis W83 grown to exponential or stationary phase were treated with poly-P75 at 1/4 to 4 MIC using inocula of 105 to 109 CFU/ml. Viable cells were enumerated following 24 h of incubation.

UV-visible spectroscopy of heme pigments.

Heme pigments from P. gingivalis were obtained by a modification of the procedure described previously (47). Briefly, 5% sheep blood agar plates containing poly-P75 at sub-MIC concentrations were prepared. Lawn growths were cultured by heavy inoculation over the whole surface of the plates, and they were incubated at 37°C anaerobically. After 4 days, the cells were gently scraped from the plates, suspended in 500 μl of NaCl-Tris buffer (0.14 M NaCl, 0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]), and sonicated using a Vibra Cell VC600 (Sonics Material, Newtown, CT) tip sonicator for 2 min to wash the pigment from the cells. The suspensions were centrifuged at 11,000 × g for 10 min at 20°C, and 200 μl of the supernatant was used for UV-visible spectroscopy. UV-visible spectra of the extracted heme pigments were recorded between 340 and 700 nm using UV-transparent microplates (UV-Star; Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC) on a Benchmark Plus Microplate Spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Accumulation and active uptake of hemin.

The amount of hemin associated with P. gingivalis cells was measured by a modification of a procedure described previously (10). Briefly, P. gingivalis cells were adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1, and one aliquot of the cells was left untreated while the other aliquot was treated with 100 μM CCCP. After a 90-min incubation, each culture was centrifuged, washed twice, resuspended, and adjusted to an OD600 of 0.2 in a new broth with or without poly-P75 and DFO at the indicated concentrations. Hemin was then added to give a final concentration of 5 μM. Following incubation at 37°C for 2 h anaerobically, a 1.0-ml aliquot was removed from each culture and centrifuged, and the supernatant was assayed spectrophotometrically (OD400). The concentration of hemin was calculated from a hemin standard curve. Cell-associated hemin was calculated as the difference between the total amount of hemin added and the amount remaining in the supernatant after the 2-h incubation and normalized against the protein content of that culture. The energy-driven active uptake of hemin was calculated as the difference between the amounts of cell-associated hemin of non-CCCP-treated and CCCP-treated cells.

QRT-PCR.

A P. gingivalis culture grown to early exponential phase was adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1 and divided in half. One half was left untreated, while the other half was treated with 0.03% poly-P75. After anaerobic incubation for 2 h, the cells were harvested, and total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). cDNA was synthesized with 1 μg of total RNA using the SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). To identify the expression value of genes related to hemagglutination, hemolysis, proteolysis, hemin uptake, chromosome replication, energy production, and iron storage and oxidative stress, quantitative real-time PCR (QRT-PCR) was performed using specific primers for the selected genes (Table 1). The housekeeping genes for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapA), 50S ribosomal protein L4 (rplD), and UDP-glucose 4-epimerase (galE) were also included as control genes in this assay.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for QRT-PCR

| Target gene | Putative identification | Primer sequence (5′-3′)a | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA | F:TGTTACAATGGGAGGGACAAAGGG | 12 | |

| R:TTACTAGCGAATCCAGCTTCACGG | |||

| galE | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase | F:TCGGCGATGACTACGACAC | 27 |

| R:CGCTCGCTTTCTCTTCATTC | |||

| gapA | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, type I | F:GGCAAACTGACGGGTATGTC | This study |

| R:ATGAAGTCGGAGGAAACCAC | |||

| rplD | 50S ribosomal protein L4 | F:CCCGAGGTGAATAAGAATGTG | This study |

| R:TAACAACGGCAACAGAACG | |||

| atpA | ATP synthase subunit A | F:ATCAGGACGGGAAAGACCAC | This study |

| R:ACGATGGGGTTGAAAGTGTC | |||

| cydA | Cytochrome d ubiquinol oxidase, subunit I | F:TGGATTCTTATCGCCAATGC | This study |

| R:ATACGCCCAAAGCAAATACG | |||

| dnaG | DNA primase | F:GACACAGGGCTTTCCATCC | This study |

| R:GCGAGCAATCTCTTTCTTGG | |||

| ligA | DNA ligase | F:CTTCACGAGGGAGACTTTGTC | This study |

| R:GTCCTTTCTGCTGCTGTGG | |||

| dps | Dps family protein | F:CAGAAGTGAAGGAAGAGCACGAAC | This study |

| R:GTAGGCAGACAGCATCCAAACG | |||

| rbr | Rubrerythrin | F:TCCACGGCTGAGAACTTGCG | This study |

| R:TGCTCGGCTTCCACCTTTGC | |||

| ftn | Ferritin | F:CGTGGCGGCGAGGTGAAG | This study |

| R:CGGAAGCAGCCCTTACGACAG | |||

| sodB | Superoxide dismutase, Fe-Mn | F:GCCAAACCCTCAACCACAATCTC | This study |

| R:GCCATACCCAGCCCGAACC | |||

| hmuY | HmuY protein | F:GGCTACTACCGTTCCGACAG | 51 |

| R:ATCCCTGTGCGTTCTTCTTG | |||

| hmuR | TonB-dependent receptor HmuR | F:GCGACGGACAGAAATACGAT | 51 |

| R:GCCTGCAACATTCAGTTCCT | |||

| ihtB (fetB) | Heme-binding protein FetB | F:TATTGCCGAACTGAAAGAAACC | 51 |

| R:TGCCATTGTCCAGCTTGTC | |||

| tla (tlr) | TonB-linked receptor Tlr | F:CCTGCGGGAACGGACAATATC | 51 |

| R:GCTACCGCCGAAGAGAGAAAC | |||

| hagA | Hemagglutinin protein HagA | F:ACAGCATCAGCCGATATTCC | 31 |

| R:CGAATTCATTGCCACCTTCT | |||

| hagB | Hemagglutinin protein HagB | F:TGTCACTTGACACTGCTACCAA | 31 |

| R:ATTCAGAGCCAAATCCTCCA | |||

| rgpA | Arginine-specific cysteine proteinase | F:GCCGAGATTGTTCTTGAAGC | 31 |

| R:AGGAGCAGCAATTGCAAAGT | |||

| rgpB | Arginine-specific cysteine proteinase | F:CGCTGATGAAACGAACTTGA | 31 |

| R:CTTCGAATACCATGCGGTTT | |||

| kgp | Lysine-specific cysteine proteinase | F:GCTTGATGCTCCGACTACTC | 13 |

| R:GCACAGCAATCAACTTCCTAAC |

F, forward; R, reverse.

QRT-PCR was carried out using the MiniOpticon Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) with a reaction mixture containing 10 μl of iQ SYBR Green SuperMix (Bio-Rad), 1 μl of cDNA, and primers to a final concentration of 250 nM in a final volume of 20 μl. To confirm that a single PCR product was amplified, melting curve analysis was performed under the following conditions: 65°C to 95°C, with a heating rate of 0.2°C per s. All quantifications were normalized to the P. gingivalis 16S rRNA gene.

Electron microscopy.

A P. gingivalis culture grown to exponential phase (OD600 = 0.3) was divided in half. One half was left untreated, while the other half was treated with 0.03% poly-P75. After anaerobic incubation for 6 and 12 h, the cells from 1 ml of each culture were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The cell pellets were washed with PBS (pH 7.4) twice and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 1 h. After being washed with PBS, the cell pellets were postfixed with 2% osmium tetroxide at 4°C for 90 min. The fixed cells were dehydrated in an ethanol series, transferred to propylenoxide, and embedded in Epon 812. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined under a Tecnai12 transmission electron microscope (Philips, Eindhoven, Netherlands) at an accelerating voltage of 120 kV.

RESULTS

Bactericidal effect of poly(P) against P. gingivalis W83.

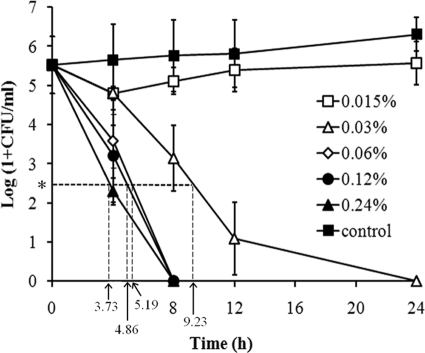

The growth of P. gingivalis W83 on brucella agar was inhibited by PPi and poly(P), but not by Pi (Table 2). MICs of PPi and all the tested poly(P), including calgon, were 0.24 and 0.06%, respectively. For further experiments, poly-P75 was chosen. According to CLSI guidelines, the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) is defined as the minimum concentration needed to kill ≥99.9% (≥3 log10) of the viable organisms after a 24-h incubation relative to the starting inoculum (33). In time-kill experiments using a starting inoculum of 105 CFU/ml, the bactericidal effect of poly-P75 was observed at concentrations as low as 0.03%, half of the MIC value assessed on the brucella agar plate. The times to achieve a 3 log10 kill were calculated from the linear portion of the kill curve (21) and were 9.23, 5.19, 4.86, and 3.73 h with 0.03%, 0.06%, 0.12%, and 0.24% poly-P75, respectively (Fig. 1). In the presence of poly-P75 (0.06% to 0.24%), P. gingivalis cells were killed at similar rates, and complete killing was observed at 8 h. Even 0.03% poly-P75 killed P. gingivalis cells grown to stationary phase with the inoculum of 109 CFU/ml, as well as bacterial cells grown to exponential phase with the inoculum of 106 to 108 CFU/ml, showing ≥3 log10 CFU/ml reduction (99.9% kill) in 24 h (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Inhibitory effects of poly(P) with various chain lengths on the growth of P. gingivalis W83

| Poly(P) | Bacterial growtha at concn (%): |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.48 | |

| Pi | + | + | + | + | + |

| PPi | + | + | + | − | − |

| Poly-P3 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Poly-P15 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Poly-P25 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Poly-P35 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Poly-P45 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Poly-P65 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Poly-P75 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Calgon | + | − | − | − | − |

+, bacterial growth; −, no growth.

FIG. 1.

Time-kill curve of poly-P75 against P. gingivalis W83. The results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. In the presence of poly-P75 (0.06% to 0.24%), complete killing of P. gingivalis cells was observed at 8 h. The asterisk indicates 3 log10 kill.

UV-visible spectra of the pigments from P. gingivalis.

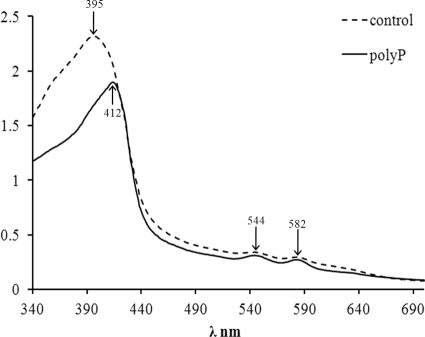

P. gingivalis degrades oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin, resulting in generation of both 385- and 393-nm-absorbing products that originated from μ-oxo bisheme in the UV-visible spectrum (46). To examine the influence of poly(P) on the formation of μ-oxo bisheme on the surface of P. gingivalis W83 grown on blood agar, we performed UV-visible spectroscopy. Incubation of P. gingivalis cells as a lawn growth on a blood agar plate without poly-P75 gave a green-black coloration after 4 days. The UV-visible spectrum of the pigment was characterized by a Soret band with a λmax value (wavelength of maximum absorption) of 395 nm and with weak Q bands positioned at approximately 544 and 582 nm (Fig. 2). On the other hand, the UV-visible spectrum of the pigment extracted from the bacterial cells grown on a blood agar plate containing poly-P75 (0.04% and 0.05%) revealed the presence of a Soret band with a λmax value of 412 nm. The 544- and 582-nm Q bands appeared more distinct than the control.

FIG. 2.

UV-visible spectra of the heme pigments washed from P. gingivalis W83 grown for 4 days on a blood agar plate with (solid line) or without (dashed line) poly-P75 at 0.04%. All spectra were recorded at room temperature in NaCl-Tris buffer (pH 7.5).

Accumulation and active uptake of hemin by P. gingivalis.

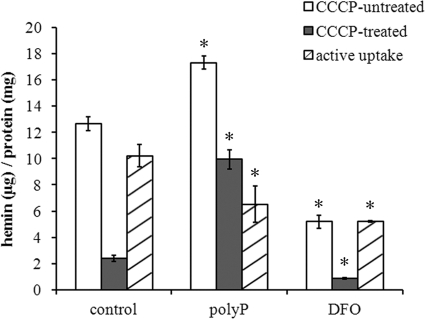

To examine the influence of poly(P) on hemin accumulation on P. gingivalis and active transport of the accumulated hemin into the cell, we used a spectrophotometric assay. The amount of hemin associated with non-CCCP-treated cells increased by 1.4-fold in the presence of 0.03% poly-P75 (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3). Poly-P75 also increased the amount of hemin associated with CCCP-treated cells by 4.2-fold (P < 0.0001). In contrast, DFO decreased the amount of cell-associated hemin by 2.5-fold (P < 0.00001) and 2.8-fold (P < 0.001) for non-CCCP-treated and treated cells, respectively. The energy-driven active uptake of hemin by P. gingivalis, calculated as the difference between the amounts of cell-associated hemin of non-CCCP-treated versus CCCP-treated cells, was 1.6- and 2.0-fold reduced in the presence of poly-P75 (P < 0.05) and DFO (P < 0.001), respectively.

FIG. 3.

Amount of hemin associated with P. gingivalis W83. Cells were treated or not with 100 μM CCCP. After a 2-h incubation in the presence or absence of 0.03% poly-P75 and 0.5% DFO, cell-associated hemin was measured spectrophotometrically as described in Materials and Methods. Energy-driven active uptake of hemin (active uptake) was calculated as the difference between binding of hemin of non-CCCP-treated cells versus that of CCCP-treated cells. The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent experiments. The asterisks indicate significant differences compared to the control as determined by Student's t test (P < 0.05).

Differential expression of the genes related to hemin uptake, hemagglutination, hemolysis, energy production, chromosome replication, and iron storage and oxidative stress.

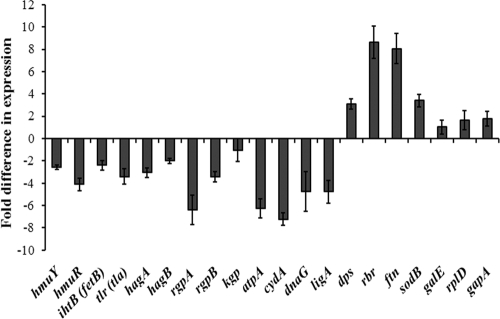

Expression of the genes related to iron storage and oxidative stress (Dps, rubrerythrin, ferritin, and superoxide dismutase genes) was upregulated, while that of the genes encoding gingipains (RgpA and RgpB), hemagglutinins (HagA and HagB), and hemin uptake loci (HmuY, HmuR, IhtB, and Tlr) was downregulated by 0.03% poly-P75 (Fig. 4). Expression of the genes related to energy production (atpA and cydA) and chromosome replication (dnaG and ligA) was also downregulated by poly-P75. The expression levels of gapA, rplD, and galE selected as control genes were not significantly affected by poly-P75.

FIG. 4.

Expression levels of the genes related to hemin uptake, hemagglutination, hemolysis, proteolysis, energy production, chromosome replication, and iron storage and oxidative stress in the presence of 0.03% poly-P75. galE, rplD, and gapA were used as control genes. Gene expression was measured by QRT-PCR and normalized to that of the 16S rRNA gene. The expression level of each gene in the absence of poly-P75 was set as 1-fold. The results are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

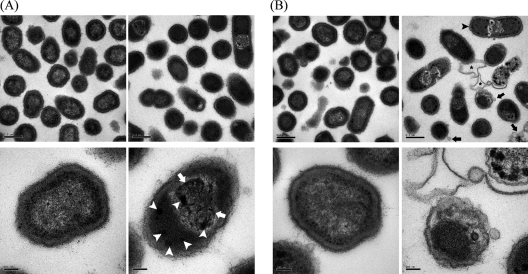

Electron microscopy.

Under a transmission electron microscope, the majority of the cells treated with poly-P75 appeared to be atypical in their shape, demonstrating highly electron-dense granules in the cytoplasm, bodies of condensed nucleoid, wave-like cell envelope, and outer membrane vesicles. Ghost cells were occasionally observed. Most of the P. gingivalis cells treated with 0.03% poly-P75 revealed a higher electron density of the cytoplasm than the cells without poly-P75 (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Transmission electron micrographs of P. gingivalis W83. The bacterium was grown to an optical density of 0.3 at 600 nm and subjected to additional 6-h (A) and 12-h (B) incubations in the absence (left) and presence (right) of 0.03% poly-P75. Note that morphologically atypical cells having highly electron-dense granules in the cytoplasm (white arrowheads), confined nucleoid (white arrows), and wavy cell envelope (black arrowhead) appeared in the presence of poly-P75. Ghost cells (asterisks) and outer membrane vesicles (black arrows) were also observed.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, poly(P) was demonstrated to be an effective antibacterial agent against P. gingivalis, a Gram-negative anaerobic rod associated with periodontal disease. The MIC of poly(P) for the bacterium was 0.06%, which is much lower than the MICs previously reported for Gram-positive bacteria; the MICs of poly(P) have been determined to be 0.1 to 0.2% for mutans streptococci and 0.5% for S. aureus and L. monocytogenes (14, 17, 52). The MIC (0.06%) of poly(P) generated by the CLSI agar dilution method (Table 2) was 1 dilution higher than the MBC (0.03%) determined by using broth (Fig. 1). Similar results were reported by Kenny et al. (16), who evaluated the CLSI standard agar dilution, tube broth dilution, and broth microdilution; agar dilution MICs tended to be slightly higher than MICs generated by other methods.

Poly(P) has bactericidal effect against S. aureus in which lysis is attributed to chelation of structurally essential metal ions in their membranes by poly(P) (22-24). In a previous study using B. cereus (28), another mechanism was proposed for the antimicrobial activity of poly(P). Because of its metal ion-chelating nature, poly(P) may have an effect on the ubiquitous bacterial cell division protein FtsZ, whose GTPase activity is strictly dependent on divalent metal ions. In the study, the bacteriolytic activity of poly(P) against B. cereus was strictly dependent on active growth and cell division. Hence, poly(P) failed to induce lysis of the cells in stationary phase. A sublethal concentration of poly(P) (0.05%) inhibited septation and cell division of B. cereus, resulting in the formation of aseptate and elongated cells. In the present study, however, the MBC of poly-P75 for P. gingivalis was 0.03% irrespective of the growth phase, as described above. Moreover, we could not observe any P. gingivalis cells with obviously aseptate and elongated morphology after 6-h and 12-h incubations with 0.03% poly-P75 under a transmission electron microscope (Fig. 5). These results suggest that the mode of bactericidal action of poly(P) against P. gingivalis is different from that against Gram-positive bacteria.

In the present study, the pigment extracted from P. gingivalis W83 grown without poly(P) gave a Soret band with a λmax value of 395 nm, indicating that the bacterial cells formed μ-oxo bisheme under the given conditions within 4 days. The slight discrepancy in λmax values presented here with those presented by Smalley et al. (46) may be due to the different incubation times and path lengths. During the same period, however, the bacterial cells grown with poly-P75 at sub-MIC concentrations generated a Soret band with a λmax value of 412 nm and distinct Q bands positioned at approximately 544 and 582 nm. This result clearly indicates that poly(P) inhibited the process of μ-oxo bisheme formation. These findings were confirmed by our QRT-PCR, in which the substantial downregulation of rgpA, rgpB, and hemagglutinins was observed in the presence of poly-P75. Even though marked depression of kgp was not observed, the suppressed formation of μ-oxo bisheme may be explained by the fact that either RgpA or RgpB, or both, with Kgp activity is required by P. gingivalis to produce μ-oxo bisheme (45).

The surface-accumulated hemin is transported into a bacterial cell to be utilized. To evaluate the effect of poly(P) on active uptake of hemin by P. gingivalis, we compared poly-P75 to DFO, an iron chelator that forms complexes with not only iron, but also hemin, via the iron moiety and prevents hemin binding to red blood cell membranes (49). Hemin uptake was shown to be inhibited by the addition of CCCP to P. gingivalis culture, indicating that energy-driven transport is required for hemin uptake. The amount of cell-associated hemin was reduced by DFO even in the absence of CCCP. It indicates that chelation of iron/hemin with DFO limits the iron/hemin availability, which in turn decreases hemin transport by P. gingivalis. Similarly, poly-P75 decreased uptake of hemin by the bacterium. The selected genes involved in the hemin uptake system, hmuY, hmuR, ihtB (also known as fetB), and tlr (also known as tla), were downregulated by poly-P75. Interestingly, unlike DFO, poly-P75 increased the amount of cell-associated hemin irrespective of CCCP treatment, which suggests that surplus hemin is accumulated on the bacterial cell surface regardless of energy-driven transport in the presence of poly(P). This result is in accordance with our previous observation, i.e., the pellet of P. gingivalis W83 cells grown in liquid medium supplemented with hemin appeared darker in the presence of poly(P) (unpublished data). The formation of μ-oxo bisheme represents an oxidative buffer mechanism for inducing an anaerobic miroenvironment and protects from hemin-mediated cell damage (25, 44, 48). Therefore, excessive accumulation of hemin in the vicinity of the bacterial cell surface without formation of μ-oxo bisheme by the bacterium may cause oxidative stress on P. gingivalis. This expectation was confirmed by our QRT-PCR, in which upregulation of the genes involved in oxidative stress, such as dps, rbr, ftn, and sodB, was observed (Fig. 4). An oxidative-stress-like phenomenon is one of the shared downstream events leading to bacterial cell death initiated by bactericidal antibiotics (50). Moreover, during bacterial cell death, genes for energy production (genes throughout the tricarboxylic acid [TCA] cycle and genes for ATP generation), chromosome replication, and nucleotide metabolism are inactivated (2). Hence, our observation of the oxidative-stress-like response of P. gingivalis and depressed expression of the genes for ATP synthesis and chromosome replication of the bacterium grown with poly(P) may also support the idea that poly(P) has a bactericidal effect.

Hemin is central to the physiology and virulence of P. ginigivalis; hemin can serve as an iron source. The redox potential of hemin, required as a prosthetic group of cytochrome b, allows it to mediate electron transfer with generation of cellular energy that is required for growth and propagation of P. gingivalis (25, 42). Hemin also has a regulatory effect on expression of protease activity that is considered to contribute to the corruption of the innate immunity of the human host. In dental biofilm, the protease activity of P. gingivalis also provides protection to its commensal partners, such as Fusobacterium nucleatum, that are sensitive to antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) through proteolytic degradation of AMPs (30, 36, 43). Also, poly(P) can stimulate bone formation (11). In this regard, using poly(P) for controlling bacterial infection and aiding the innate immune system, as well as promoting bone regeneration, seems a fascinating strategy for the prevention and treatment of periodontal disease. Applying such a strategy, however, requires further study to ensure the effectiveness of poly(P) in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Mid-Career Researcher Program through an NRF grant funded by the MEST (R01-2007-000-20985-0), Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anaya-Bergman, C., et al. 2010. Porphyromonas gingivalis ferrous iron transporter FeoB1 influences sensitivity to oxidative stress. Infect. Immun. 78:688-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asakura, Y., and I. Kobayashi. 2009. From damaged genome to cell surface: transcriptome changes during bacterial cell death triggered by loss of a restriction-modification gene complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:3021-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avetisyan, A., P. Dibrov, V. Skulachev, and M. Sokolov. 1989. The Na+-motive respiration in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 254:17-21. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bramanti, T. E., and S. C. Holt. 1991. Roles of porphyrins and host iron transport proteins in regulation of growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. J. Bacteriol. 173:7330-7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, A., and R. Ruh, Jr. 1977. Negative interaction of orthophosphate with glycolytic metabolism by Streptococcus mutans as a possible mechanism for dental caries reduction. Arch. Oral Biol. 22:521-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carman, R. J., M. D. Ramakrishnan, and F. H. Harper. 1990. Hemin levels in culture medium of Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis regulate both hemin binding and trypsinlike protease production. Infect. Immun. 58:4016-4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu, L., T. E. Bramanti, J. L. Ebersole, and S. C. Holt. 1991. Hemolytic activity in the periodontopathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis: kinetics of enzyme release and localization. Infect. Immun. 59:1932-1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2007. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria; approved standard. 7th ed. Document M11-A7. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 9.Darveau, R. P., A. Tanner, and R. C. Page. 1997. The microbial challenge in periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000 14:12-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Genco, C. A., B. M. Odusanya, and G. Brown. 1994. Binding and accumulation of hemin in Porphyromonas gingivalis are induced by hemin. Infect. Immun. 62:2885-2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hacchou, Y., et al. 2007. Inorganic polyphosphate: a possible stimulant of bone formation. J. Dent. Res. 86:893-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosogi, Y., and M. J. Duncan. 2005. Gene expression in Porphyromonas gingivalis after contact with human epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 73:2327-2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James, C. E., et al. 2006. LuxS involvement in the regulation of genes coding for hemin and iron acquisition systems in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 74:3834-3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jen, C. M., and L. A. Shelef. 1986. Factors affecting sensitivity of Staphylococcus aureus 196E to polyphosphates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:842-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karunakaran, T., and S. C. Holt. 1993. Cloning of two distinct hemolysin genes from Porphyromonas gingivalis in Escherichia coli. Microb. Pathog. 15:37-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kenny, M. T., J. K. Dulworth, and M. A. Brackman. 1989. Comparison of the agar dilution, tube dilution, and broth microdilution susceptibility tests for determination of teicoplanin MICs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:1409-1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knabel, S., H. Walker, and P. Harman. 1991. Inhibition of Aspergillus flavus and selected gram-positive bacteria by chelation of essential metal cations by polyphosphates. J. Food. Prot. 54:360-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kornberg, A., N. N. Rao, and D. Ault-Riché. 1999. Inorganic polyphosphate: a molecule of many functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68:89-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamont, R. J., and H. F. Jenkinson. 1998. Life below the gum line: pathogenic mechanisms of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1244-1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanigan, R. S. 2001. Final report on the safety assessment of sodium metaphosphate, sodium trimetaphosphate, and sodium hexametaphosphate. Int. J. Toxicol. 20(Suppl. 3):75-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson, A. J., K. J. Walker, J. K. Raddatz, and J. C. Rotschafer. 1996. The concentration-independent effect of monoexponential and biexponential decay in vancomycin concentrations on the killing of Staphylococcus aureus under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 38:589-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, R. M., P. A. Hartman, D. G. Olson, and F. D. Williams. 1994. Bactericidal and bacteriolytic effects of selected food-grade phosphates, using Staphylococcus aureus as a model system. J. Food. Prot. 57:276-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, R. M., P. A. Hartman, D. G. Olson, and F. D. Williams. 1994. Metal ions reverse the inhibitory effects of selected food-grade phosphates in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Food. Prot. 57:284-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, R. M., P. A. Hartman, H. M. Stahr, D. G. Olson, and F. D. Williams. 1994. Antibacterial mechanism of long-chain polyphosphates in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Food. Prot. 57:289-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis, J. P., J. A. Dawson, J. C. Hannis, D. Muddiman, and F. L. Macrina. 1999. Hemoglobinase activity of the lysine gingipain protease (Kgp) of Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. J. Bacteriol. 181:4905-4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis, J. P. 2010. Metal uptake in host-pathogen interactions: role of iron in Porphyromonas gingivalis interactions with host organisms. Periodontol. 2000 52:94-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lo, A., et al. 2010. FimR and FimS: biofilm formation and gene expression in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 192:1332-1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maier, S. K., S. Scherer, and M. J. Loessner. 1999. Long-chain polyphosphate causes cell lysis and inhibits Bacillus cereus septum formation, which is dependent on divalent cations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3942-3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcy, J., et al. 1988. Effects of selected commercial phosphate products on the natural bacterial flora of a cooked meat system. J. Food Sci. 53:391-393, 577. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marsh, P. D., A. S. McDermid, A. S. McKee, and A. Baskerville. 1994. The effect of growth rate and haemin on the virulence and proteolytic activity of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. Microbiology 140:861-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meuric, V., P. Gracieux, Z. Tamanai-Shacoori, J. Perez-Chaparro, and M. Bonnaure-Mallet. 2008. Expression patterns of genes induced by oxidative stress in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 23:308-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Molins, R. A., et al. 1987. Effect of inorganic polyphosphates on ground beef characteristics: microbiological effects on frozen beef patties. J. Food Sci. 52:46-49. [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1999. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents. Approved guideline. Document M26-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 34.Obritsch, J. A., D. Ryu, L. E. Lampila, and L. B. Bullerman. 2008. Antibacterial effects of long-chain polyphosphates on selected spoilage and pathogenic bacteria. J. Food Prot. 71:1401-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Post, F. J., G. B. Krishnamurty, and M. D. Flanagan. 1963. Influence of sodium hexametaphosphate on selected bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. 11:430-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Potempa, J., and R. N. Pike. 2009. Corruption of innate immunity by bacterial proteases. J. Innate Immun. 1:70-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajkowski, K. T., S. M. Calderone, and E. Jones. 1994. Effect of polyphosphate and sodium chloride on the growth of Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus in ultra-high temperature milk. J. Dairy Sci. 77:1503-1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ratnayake, D. B., et al. 2000. Ferritin from the obligate anaerobe Porphyromonas gingivalis: purification, gene cloning and mutant studies. Microbiology 146:1119-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shibata, H., and T. Morioka. 1982. Antibacterial action of condensed phosphates on the bacterium Streptococcus mutans and experimental caries in the hamster. Arch. Oral Biol. 27:809-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shibata, Y., et al. 2003. A 35-kDa co-aggregation factor is a hemin binding protein in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 300:351-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slakeski, N., et al. 2000. A Porphyromonas gingivalis genetic locus encoding a heme transport system. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 15:388-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smalley, J. W., A. J. Birss, A. S. McKee, and P. D. Marsh. 1998. Hemin regulation of hemoglobin binding by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Curr. Microbiol. 36:102-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smalley, J. W., A. J. Birss, A. S. McKee, and P. D. Marsh. 1991. Haemin-restriction influences haemin-binding haemagglutination and protease activity of cells and extracellular membrane vesicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 90:63-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smalley, J. W., A. J. Birss, B. Szmigielski, and J. Potempa. 2006. The HA2 haemagglutinin domain of the lysine-specific gingipain (Kgp) of Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes μ-oxo bishaem formation from monomeric iron (III) protoporphyrin IX. Microbiology 152:1839-1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smalley, J. W., A. J. Birss, B. Szmigielski, and J. Potempa. 2007. Sequential action of R- and K-specific gingipains of Porphyromonas gingivalis in the generation of the haem-containing pigment from oxyhaemoglobin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 465:44-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smalley, J. W., A. J. Birss, R. Withnall, and J. Silver. 2002. Interactions of Porphyromonas gingivalis with oxyhaemoglobin and deoxyhaemoglobin. Biochem. J. 362:239-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smalley, J. W., M. F. Thomas, A. J. Birss, R. Withnall, and J. Silver. 2004. A combination of both arginine- and lysine-specific gingipain activity of Porphyromonas gingivalis is necessary for the generation of the μ-oxo bishaem-containing pigment from haemoglobin. Biochem. J. 379:833-840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smalley, J. W., A. J. Birss, and J. Silver. 2000. The periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis harnesses the chemistry of the μ-oxo bishaem of iron protoporphyrin IX to protect against hydrogen peroxide. FEMS Microbiology Lett. 183:159-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sullivan, S. G., E. Baysal, and A. Stern. 1992. Inhibition of hemin-induced hemolysis by desferrioxamine: binding of hemin to red cell membranes and the effects of alteration of membrane sulfhydryl groups. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1104:38-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wright, G. D. 2007. On the road to bacterial cell death. Cell 130:781-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu, J., X. Lin, and H. Xie. 2009. Regulation of hemin binding proteins by a novel transcriptional activator in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 191:115-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zaika, L., and A. Kim. 1993. Effect of sodium polyphosphates on growth of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Prot. 56:577-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]