Abstract

CD4+ T cells have been shown to be essential for vaccine-induced protection against Helicobacter pylori infection in mice. Less is known about the relative contributions of individual cell subpopulations, such as Th1 and Th17 cells, and their associated cytokines. The aim of the present study was to find immune correlates to vaccine-induced protection and further study their role in protection against H. pylori infection. Immunized and unimmunized mice were challenged with H. pylori, and immune responses were compared. Vaccine-induced protection was assessed by measuring H. pylori colonization in the stomach. Gastric gene expression of Th1- and/or Th17-associated cytokines was analyzed by quantitative PCR, and contributions of individual cytokines to protection were evaluated by antibody-mediated in vivo neutralization. By analyzing immunized and unimmunized mice, a significant inverse correlation between the levels of interleukin-12p40 (IL-12p40), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF), gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and IL-17 gene expression and the number of H. pylori bacteria in the stomachs of individual animals after challenge could be demonstrated. In a kinetic study, upregulation of TNF, IFN-γ, and IL-17 coincided with vaccine-induced protection at 7 days after H. pylori challenge and was sustained for at least 21 days. In vivo neutralization of these cytokines during the effector phase of the immune response revealed a significant role for IL-17, but not for IFN-γ or TNF, in vaccine-induced protection. In conclusion, although both Th1- and Th17-associated gene expression in the stomach correlate with vaccine-induced protection against H. pylori infection, our study indicates that mainly Th17 effector mechanisms are of critical importance to protection.

Helicobacter pylori infects the stomachs of approximately half of the world's population, thereby constituting a global health problem. Although the majority of H. pylori-infected individuals remain asymptomatic, H. pylori infection is the cause of severe disease such as peptic ulcers or gastric cancer in 10 to 20% of infected individuals (17). The current treatment based on antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor is, when available, usually effective, but it is also associated with several disadvantages such as poor patient compliance, increasing development of antibiotic-resistant strains, high costs of treatment, and no protection against reinfection (17, 23). Therefore, the development of a vaccine remains an attractive approach for the global control of H. pylori infection.

Infection with H. pylori is associated with an infiltration of neutrophils, macrophages, eosinophils, and lymphocytes to the site of inflammation, mediated through the induction of cytokines and chemokines (21, 36). Despite a local accumulation of immune cells, the infection is rarely cleared spontaneously. Several studies of vaccination against H. pylori infection in animal models have reported measurable protection, resulting in reduction of the bacterial load in the stomach. Protection has been reported after both prophylactic and therapeutic immunization with H. pylori antigens, most often using cholera toxin (CT) as a mucosal adjuvant (reviewed in reference 40). Although it is known from these models that the ability to clear H. pylori infection is associated with gastritis (3, 6, 10, 28), immune correlates to vaccine-induced protection remain poorly defined (2), which is a major limitation to further development of a vaccine for human use.

An indispensable role for CD4+ T cells in protection against H. pylori infection has clearly been shown in mice (7, 26). Studies in IFN-γ−/− mice have identified gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-producing Th1 cells as an important subpopulation of CD4+ T cells responsible for conferring protection against H. pylori infection in immunized animals (3, 32, 33). More recent studies have also indicated a major role for interleukin-17 (IL-17)-producing Th17 cells as a mediator for vaccine-induced protection, acting via chemokine induction in the stomach and subsequent attraction of neutrophils (6, 41). Furthermore, several proinflammatory cytokines have been shown to be involved in protection against H. pylori in primary-infected mice and/or in immunized mice after H. pylori challenge (3, 4, 9, 33, 41, 42). However, the identification of these cytokines is based mainly on experiments performed with gene knockout mice, and in these mice it is not possible to separate the contributions of the specific cytokine during the induction and the effector phase of an immune response. A comparison of the relative contributions of IFN-γ and IL-17, the hallmark cytokines of Th1 and Th17 cells, respectively, to protection is also lacking.

In the present study we have examined gene expression of cytokines suggested to be important for protection against H. pylori infection in the stomachs of immunized and unimmunized mice. Increased mRNA levels of IL-12p40, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF), IFN-γ, and IL-17 were found to be strongly correlated with reduced bacterial numbers in the stomachs of mice after challenge with live H. pylori bacteria. Expression of the last three cytokines was elevated at 1 week after challenge in immunized mice compared to unimmunized mice, which was also the earliest time point when vaccine-induced protection was observed. In vivo neutralization of these cytokines with specific antibodies confirmed a significant role for IL-17, but not for IFN-γ or TNF, in vaccine-induced protection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Female 6- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Taconic and housed in microisolators at the Laboratory for Experimental Biomedicine, University of Gothenburg, during the study. All experiments were approved by the ethical committee for animal experiments (Gothenburg, Sweden).

Preparation of antigens for immunization.

Mice were immunized with three different antigen preparations. (i) A preparation of lysed bacteria (here referred to as lysate) of a clinical isolate of H. pylori bacteria (strain Hel 305, CagA+ VacA+) was prepared as previously described (30), and the protein content was determined using the Noninterfering Protein Assay kit (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). To reduce the volume for sublingual immunization, the lysate was freeze-dried in appropriate doses and reconstituted immediately before administration to the mice. (ii) To prepare formalin-inactivated bacteria, the N4830-I-pML-λPL-hpaA strain (a recombinant Escherichia coli strain expressing HpaA upon incubation at 42°C) was cultured at 30°C in Luria-Bertani broth (BD Biosciences, San José, CA) containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 and subsequently induced for 3 h by raising the temperature to 42°C to allow high expression of HpaA. The bacteria (here referred to as E. coli-HpaA) were collected, inactivated in 1% formalin for 1 h at 37°C, and washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). (iii) Recombinant HpaA (rHpaA) was purified from the induced N4830-I-pML-λPL-hpaA strain according to the protocol described by Sutton et al. with some modifications (39). Briefly, after lysis of the cells, two rounds of Triton X-114 extraction and further purification by application of the heavy detergent phase to a Resource Q column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden) were performed. Thereafter, the HpaA-containing fractions were loaded onto a gel filtration column (Superdex200 16/60; GE Healthcare). The resulting rHpaA preparation was concentrated, and the purity was checked by SDS-PAGE before storage at −20°C until use.

Cultivation of H. pylori used for challenge.

The mouse-adapted H. pylori Sydney strain 1 (SS1) (CagA+ VacA+ Ley) was cultured on Colombia isoagar plates under microaerophilic conditions (10% CO2, 6% O2, 84% N2) for 2 days. One part of the culture on plates was then transferred to 25 ml of brucella broth (BD Biosciences) for infection of mice as described previously (30). To calculate the infectious dose given to the mice, serial dilutions of the broth culture were plated on horse blood agar plates and the CFU were counted after 6 to 7 days of incubation.

Immunization and infection of mice.

Mice were immunized according to four different protocols: (i) prophylactic immunization consisting of four weekly 500-μg doses of H. pylori lysate given sublingually, (ii) prophylactic immunization consisting of four weekly 500-μg doses of H. pylori lysate and 10 μg CT given sublingually, (iii) prophylactic immunization consisting of two biweekly 25-μg doses of rHpaA given intragastrically, and (iv) therapeutic immunization consisting of two biweekly doses of 109 formalin-inactivated E. coli-HpaA bacteria and 10 μg CT given intragastrically. Sublingual immunizations were given in 10 μl under the tongue using a micropipette, while intragastric immunizations were given in 300 μl containing 3% sodium bicarbonate and placed directly into the stomach using a feeding needle. Prophylactically and therapeutically immunized mice were challenged with 3 × 108 H. pylori SS1 bacteria at 2 weeks after or 2 weeks before the immunization protocol, respectively.

In vivo neutralization of cytokines.

Mice were immunized sublingually with H. pylori lysate and CT and challenged as described above. To inhibit TNF, IFN-γ, or IL-17 during the effector phase of the immune response, the mice were injected intraperitoneally with 500 μg of either anti-TNF neutralizing antibody (clone XT3.11), anti-IFN-γ neutralizing antibody (clone R4-6A2) (both purchased from Bio X Cell, West Lebanon, NH), anti-IL-17A neutralizing antibody (clone JL7.1D10) (Merck Research Labs, Palo Alto, CA), or purified rat IgG control antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) on days 5, 8, and 11 after challenge. Some mice received a combination of anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-17A neutralizing antibodies. The dose of neutralizing antibodies chosen for injection was based on previous studies that have demonstrated an effect of neutralization (13, 27, 34, 41). Two weeks after challenge, the mice were sacrificed.

Quantitative culture of H. pylori SS1 from the stomachs of mice.

To determine the bacterial colonization in the stomach, mice were killed and one half of the stomach was homogenized in brucella broth (BD Biosciences) using a tissue homogenizer (Ultra Turrax; IKA Laboratory Technologies, Staufen, Germany). Serial dilutions of the homogenates were plated on Helicobacter selective plates as previously described (30). After 7 days under microaerophilic conditions, visible colonies were counted based on typical colony morphology of H. pylori.

Cytokine gene expression in whole stomach tissue. RNA isolation.

The stomach was excised and dissected along the greater curvature, and any loose stomach contents were removed by a wash in PBS. Two longitudinal strips including the antrum and the corpus were cut and placed directly into RNAlater (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The samples were kept at 4°C for 2 days before storage at −70°C until further use. For homogenization, the tissue was transferred to RLT lysis buffer (Qiagen) and treated for 2 min at 30 Hz using a Tissue Lyser II (Qiagen). Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini-isolating kit (Qiagen) according to the description of the manufacturer. The RNA was stored at −70°C until further analyzed.

Quantitative PCR.

A total of 2 μg RNA per sample was converted into cDNA using the Omniscript kit (Qiagen) according to the instructions of the manufacturer and diluted with H2O. All PCRs were run in 96-well plates by mixing cDNA with 10 μl 2× Power SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and 1 μl oligonucleotide primers (Eurofins MWG Operon, Ebersberg, Germany) (Table 1) in a total volume of 20 μl. Standard amplification conditions described for the 7500 real-time PCR system were used. The reactions were run in duplicates, and β-actin was used as the reference gene in all experiments. The difference between the target gene and the β-actin reference gene (ΔCT) was used to measure the relative amounts of the different transcripts using the formula 2ΔCT. Statistical analysis and normalization were performed using the ΔCT data.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for quantitative PCR

| Gene | Primer sequence |

|

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| TNF | 5′-TGGCCTCCCTCTCATCAGTTC-3′ | 5′-GCTACAGGCTTGTCACTCGAATTTT-3′ |

| IFN-γ | 5′-TTTAACTCAAGTGGCATAGATGTGGAA-3′ | 5′-ATCTGGCTCTGCAGGATTTTCA-3′ |

| IL-17A | 5′-CCGCAATGAAGACCCTGATAGA-3′ | 5′-TCATGTGGTGGTCCAGCTTTC-3′ |

| IL-18 | 5′-CCAGCATCAGGACAAAGAAAGC-3′ | 5′-TCTGACATGGCAGCCATTGTT-3′ |

| IL-12p40 | 5′-GCACGGCAGCAGAATAAATATGAG-3′ | 5′-TTCAAAGGCTTCATCTGCAAGTTC-3′ |

| IL-12p35 | 5′-GGGACCAAACCAGCACATTG-3′ | 5′-GCTCCCTCTTGTTGTGGAAGAAG-3′ |

| IL-23p19 | 5′-ATGCACCAGCGGGACATATG-3′ | 5′-TTGTGGGTCACAACCATCTTCA-3′ |

| IL-10 | 5′-CATTTGAATTCCCTGGGTGAGA-3′ | 5′-TGCTCCACTGCCTTGCTCTT-3′ |

| TGF-β | 5′-CACCGGAGAGCCCTGGATA-3′ | 5′-TTCCAACCCAGGTCCTTCCTAA-3′ |

| CXCL2 | 5′-CTTCAAGAACATCCAGAGCTTGAGTGT-3′ | 5′-CCCTTGAGAGTGGCTATGACTTCTGT-3′ |

| CXCL5 | 5′-CCGCTGGCATTTCTGTTGCT-3′ | 5′-GCAGCTCCGTTGCGGCTAT-3′ |

| CXCR2 | 5′-CAAGCCTTGAGTCACAGAGAGTTG-3′ | 5′-CTTTGAGGTAAACTTAATCCTGCAGTAG-3′ |

| CXCL10 | 5′-ATATCGATGACGGGCCAGTGA-3′ | 5′-TTTCATCGTGGCAATGATCTCA-3′ |

| CXCR3 | 5′-CACCAGCCAAGCCATGTACCT-3′ | 5′-GGTGCTGTTTTCCAGAAGAAAGG-3′ |

| CD4 | 5′-ACTGGTTCGGCATGACACTCT-3′ | 5′-TCCGCTGACTCTCCCTCACT-3′ |

| β-Actin | 5′-CTGACAGGATGCAGAAGGAGATTA-3′ | 5′-GCCACCGATCCACACAGAGT-3′ |

Detection of IFN-γ protein in extracts of stomach tissue.

A longitudinal strip of the stomach was weighed before incubation in PBS containing 2% saponin (Sigma), 100 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma), 350 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma), 50 mM EDTA, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) overnight at 4°C. The suspension was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min. The IFN-γ concentration in the supernatant was determined using a cytometric bead array kit (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analyses.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student's t test were used to evaluate differences between groups and Pearson's test was used to evaluate correlation, using the GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Different immunization regimens confer various levels of protection against H. pylori infection.

The main objective of this study was to find immune correlates to vaccine-induced protection against H. pylori infection in a well-established mouse model. A statistically significant reduction in the bacterial loads in the stomachs of immunized compared to unimmunized mice after challenge with an infectious dose of H. pylori was regarded as a measure of protection (30). In order to test correlation of cytokine gene expression in the stomach to the bacterial load, it is advantageous to analyze mice in which different levels of protection have been induced. Therefore, four different immunization regimens that in preliminary studies had resulted in markedly different protection levels were carried out. The protocols differed with regard to antigens, use of adjuvant, and/or route and timing of vaccination.

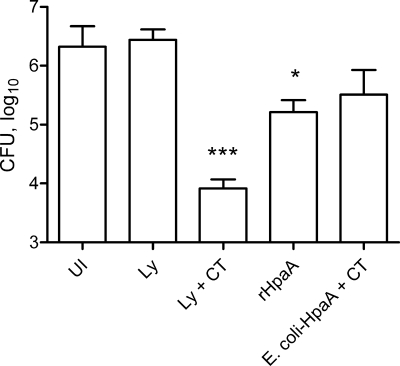

As expected, the different immunization regimens induced different levels of protection against H. pylori infection when the bacterial loads in the stomachs were compared to those in control infected, unimmunized mice (Fig. 1). The strongest protection (250-fold reduction in bacterial load) was observed after prophylactic immunization with H. pylori lysate and CT sublingually (P < 0.001). This effect was completely dependent on the presence of CT as an adjuvant, since no protection was seen in mice immunized with H. pylori lysate alone. Immunization with nonadjuvanted rHpaA induced significant protection against H. pylori infection (13-fold reduction in bacterial load, P < 0.05), indicating potent immunogenicity of the recombinant protein. Finally, although not statistically significant, a trend toward decreased bacterial load was also seen in mice therapeutically immunized with formalin-killed E. coli-HpaA and CT compared to unimmunized infected animals.

FIG. 1.

Different immunization regimens afford different degrees of protection against H. pylori infection. Mice were immunized sublingually with H. pylori lysate (Ly) with or without CT adjuvant or intragastrically with HpaA, either as a purified protein alone (rHpaA) or delivered by formalin-killed E. coli, induced to express the antigen, together with CT (E. coli-HpaA + CT). The last formulation was given after whereas the other three formulations were given before challenge with an infectious dose of H. pylori bacteria. Unimmunized (UI) mice challenged with live H. pylori bacteria served as infection controls. At 4 to 6 weeks after challenge, live H. pylori in the stomach was assessed by quantitative culture and expressed as CFU per stomach. Data are shown as mean values for groups of five to seven animals, and error bars represent standard errors of the means (SEM). Significant decreases in bacterial load compared to UI mice, as assessed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's posttest, are denoted by * (P < 0.05) and *** (P < 0.001) (overall P < 0.0001).

Protection against H. pylori infection correlates with proinflammatory cytokine gene expression in the stomach.

Stomach tissue from the animals presented in Fig. 1 was preserved in RNAlater, and real-time PCR analysis was carried out in order to determine cytokine mRNA levels. TNF, IL-12p40, IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-18 were investigated, since they have been suggested to be important for protection against H. pylori infection based on studies with mice lacking these specific cytokines (3, 4, 9, 33, 41, 42).

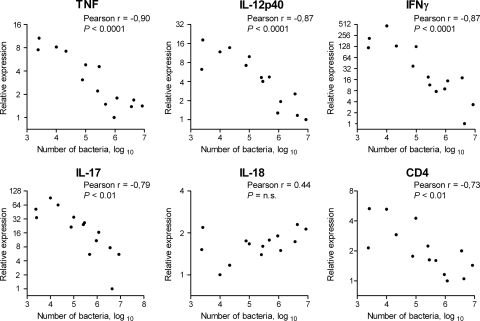

The highest expression of TNF, IL-12p40, IFN-γ, and IL-17 was detected in animals with the lowest number of bacteria in the stomach, and a significant inverse correlation between gastric cytokine gene expression and bacterial numbers in the stomach was seen for these cytokines (Fig. 2). No inverse correlation between expression of IL-18 and bacterial numbers in the stomach was detected; instead, there was tendency for high IL-18 expression to be associated with high bacterial numbers in the stomach (Fig. 2). In addition, we observed, probably as a consequence of and an attempt to balance the induced proinflammatory response, an increased expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) in immunized protected mice, which inversely correlated with H. pylori colonization (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

The gene expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the stomach correlates with protection against H. pylori infection. CFU per stomach are shown, expressed on a log10 scale and plotted against the relative amounts of TNF, IL-12p40, IFN-γ, IL-17, IL-18, and CD4 transcripts in the stomach at 4 to 6 weeks after the challenge with an infectious dose of H. pylori. The plots represent data from individual mice from the different groups presented in Fig. 1 (three mice per group). For each gene, the expression values were normalized so that the lowest value was set to 1. Correlation was evaluated by Pearson's test, and r and P values are indicated in each plot.

At the protein level, IL-12p40 can pair with either IL-12p35 or IL-23p19 to form the biologically active cytokines IL-12 and IL-23, respectively. Therefore, IL-12p35 and IL-23p19 gene expression in the stomach was additionally analyzed. Both IL-12p35 and IL-23p19 transcripts were detected in the stomach tissue, but no significant increase in expression level was seen in immunized and challenged mice compared to unimmunized control infected mice for either of the genes. Hence, no correlation between IL-12p35 or IL-23p19 mRNA expression and bacterial colonization was detected (data not shown).

In accordance with the essential role for CD4+ T cells in protection against H. pylori, we also found an inverse correlation between CD4 gene expression and H. pylori colonization in the stomach (Fig. 2).

In immunized mice, time course analysis reveals that protection against H. pylori infection coincides with enhanced cytokine gene expression in the stomach.

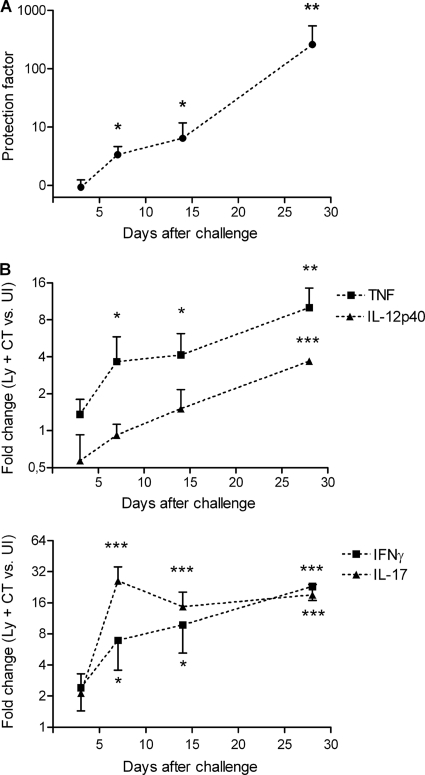

To study in greater detail the gene expression in the stomach of cytokines that correlated with protection, a kinetic study was performed in which unimmunized mice and mice sublingually immunized with H. pylori lysate and CT were analyzed at 3, 7, 14, and 28 days after H. pylori challenge in order to determine when cytokines associated with protection against H. pylori infection are elevated. When examined 3 days after challenge, no protection against H. pylori infection was evident in the immunized mice. At day 7 and day 14, similar levels of protection were observed: 3- and 6-fold decreases (P < 0.05) in bacterial load compared to that in unimmunized control infected mice, respectively (Fig. 3A). Vaccine-induced protection increased to a 300-fold reduction in bacterial load at 28 days after challenge (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Time course analysis reveals that cytokine gene expression in the stomachs of mice coincides with protection against H. pylori infection after sublingual immunization. Mice were immunized sublingually with H. pylori lysate and CT on four occasions at weekly intervals and challenged with an infectious dose of H. pylori bacteria 2 weeks later (Ly + CT). Unimmunized mice challenged at the same time served as infection controls (UI). The mice were sacrificed at days 3, 7, 14, and 28 postchallenge. (A) Live H. pylori bacteria in the stomach were assessed by quantitative culture. A ratio (UI versus Ly + CT) was calculated for each time point and expressed as a protection factor. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of TNF, IL-12p40, IFN-γ, and IL-17 was performed on stomach tissue from the same mice presented in panel A to determine cytokine transcript levels. The fold change (Ly + CT versus UI) was calculated for each time point and gene. Data are representative of two independent experiments and shown as mean values for groups of five to seven animals; error bars represent SEM. Significant protection (i.e., a decrease in bacterial load) (A) and increase in gene expression (B) in immunized mice compared to the corresponding unimmunized mice, as assessed by Student's t test, are denoted by * (P < 0.05), ** (P < 0.01), and *** (P < 0.001).

The gene expression of the cytokines TNF, IL-12p40, IFN-γ, and IL-17 largely paralleled the kinetics seen for protection. No significant differences in expression were seen between immunized and unimmunized mice at 3 days after H. pylori challenge (Fig. 3B). At day 7, the first time point when a vaccine-induced effect on the bacterial load in the stomach was observed, a simultaneous and significant elevation in TNF, IFN-γ, and IL-17 gene expression was observed in immunized mice compared to unimmunized mice (Fig. 3B). The upregulation of TNF, IFN-γ, and IL-17 genes was sustained during the whole experiment (Fig. 3B). The gastric gene expression of IL-12p40 was also upregulated in the immunized mice compared to the unimmunized mice at 28 days after H. pylori challenge, but in contrast to results for TNF, IFN-γ, and IL-17, no significant upregulation was observed at earlier time points (Fig. 3B).

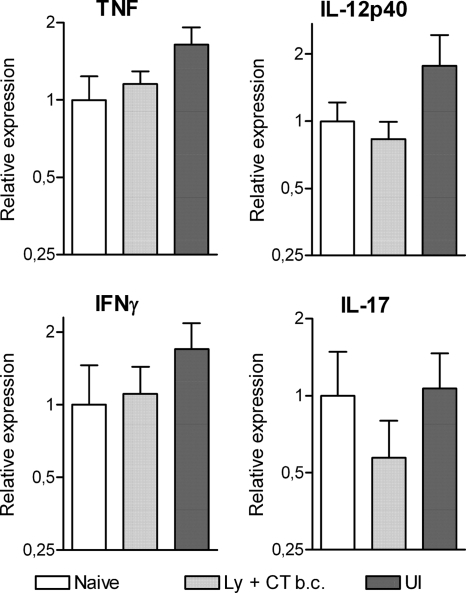

It is also striking to note that upregulation of the proinflammatory cytokines was dependent on the combination of immunization and H. pylori challenge, since neither immunized mice sacrificed before challenge nor unimmunized infected mice sacrificed 28 days after challenge showed any significant differences in gastric gene expression of IL-12p40, TNF, IFN-γ, or IL-17 compared to naïve mice (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Immunization or infection on its own does not induce proinflammatory gene expression in the stomach. Gene expression was measured in mice immunized sublingually with H. pylori lysate together with CT before challenge with live H. pylori bacteria (Ly + CT b.c.) as well as in unimmunized infected mice (UI) at day 28 postchallenge and compared to the basal gene expression detected in naïve animals. The mean level of the different transcripts was set to 1 in the naïve group for each gene. Pooled data from two independent experiments are shown as mean values for groups of five to nine animals; error bars represent SEM. No significant differences were detected for any of the investigated genes.

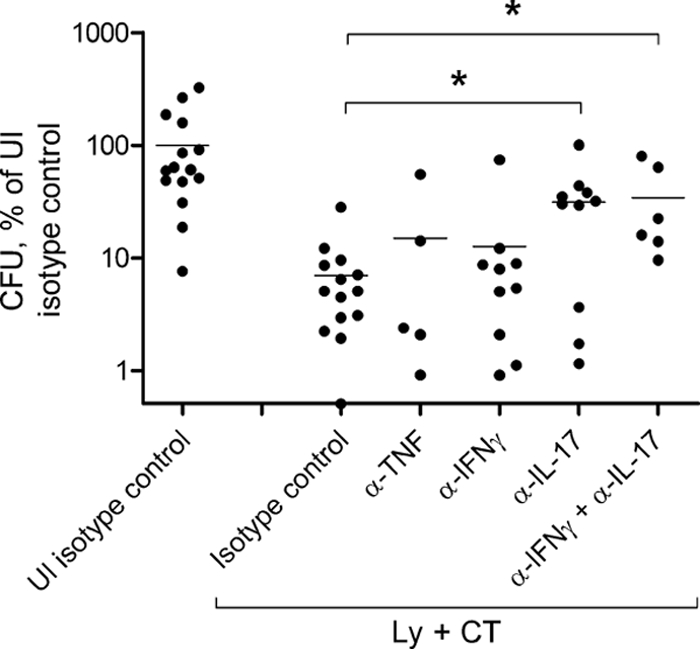

Neutralization of IL-17 has a significant impact on vaccine-induced protection against H. pylori.

Given the correlation in both magnitude and time course between increases in TNF, IFN-γ and IL-17 gene expression in the stomach and vaccine-induced protection, we sought to evaluate the effect of blocking these cytokines on the level of protection. Unimmunized and sublingually immunized (with H. pylori lysate plus CT) mice were injected intraperitoneally with neutralizing antibodies against either of the cytokines or, alternatively, with a combination of antibodies neutralizing IFN-γ and IL-17 on days 5, 8, and 11 after challenge with H. pylori. Mice were sacrificed at day 14 after challenge, a time point when we have earlier observed a vaccine-induced effect on the bacterial load in the stomach.

In unimmunized infected mice, treatment with neutralizing antibodies against TNF or IFN-γ did not significantly influence the bacterial load in the stomach compared to treatment with control IgG, while anti-IL-17 treatment resulted in a 3-fold increase in the colonization (P < 0.05), indicating a role for IL-17 in controlling initial H. pylori colonization (data not shown).

In immunized mice, neutralization of IL-17 resulted in a significant 5-fold increase in H. pylori colonization compared to that in mice injected with control IgG (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5). Neutralization of IFN-γ or TNF, on the other hand, did not have any impact on the bacterial load, and when IFN-γ and IL-17 were neutralized simultaneously, no further increase in bacterial load was observed compared to when IL-17 alone was neutralized (Fig. 5). In summary, our results suggest an important role for IL-17, but not for TNF or IFN-γ, in vaccine-induced protection against H. pylori.

FIG. 5.

Neutralization of IL-17 has a significant impact on H. pylori colonization in the stomachs of immunized mice. Mice were either immunized sublingually with H. pylori lysate and CT on four occasions (Ly + CT) or left unimmunized (UI) before challenge with an infectious dose of H. pylori bacteria. The mice were injected with the different neutralizing monoclonal antibodies or an IgG isotype control (IgG), as indicated, at days 5, 8, and 11 postchallenge and sacrificed at day 14. CFU per stomach was calculated, and values were normalized to the UI infection control group treated with isotype control antibody, in which the mean value was set to 100%. Pooled data from three independent experiments are shown; dots and horizontal bars represent individual and mean values, respectively. A significant increase in H. pylori colonization compared to the Ly + CT control, as assessed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's posttest, is denoted by * (P < 0.05) (overall P < 0.05).

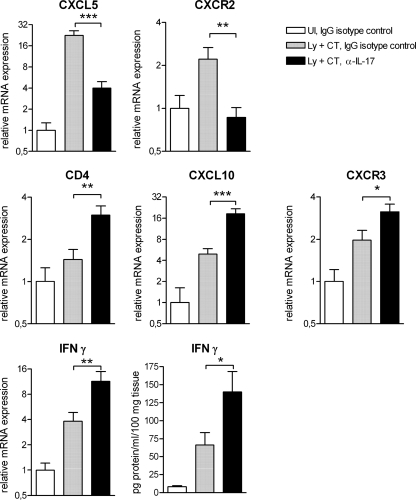

Neutralization of IL-17 promotes Th1 responses in the stomachs of immunized mice after H. pylori challenge.

Previous studies have shown an intricate interplay between IL-17-producing Th17 cells and IFN-γ-producing Th1 cells in vivo (14, 16, 24, 25). It is also known that IL-17 is important for recruitment of neutrophils to mucosal tissue through induction of chemokine expression (6). We therefore studied gene expression associated with neutrophil chemoattraction and Th1 responses in the stomachs of sublingually immunized and IL-17-neutralized mice at 14 days after H. pylori challenge.

The results showed that expression of the neutrophil chemoattractant CXCL5 (P < 0.001) and the corresponding receptor CXCR2 (P < 0.01) was decreased in IL-17-neutralized animals compared to mice injected with control IgG (Fig. 6). This indicated that the neutralization led to an interference with IL-17-mediated neutrophil recruitment to the stomach.

FIG. 6.

Neutralization of IL-17 inhibits induction of neutrophil chemoattractants and promotes Th1-associated responses in the stomachs of immunized mice after H. pylori challenge. Mice were either immunized sublingually with H. pylori lysate antigens and CT on four occasions (Ly + CT) or left unimmunized (UI) before challenge with an infectious dose of H. pylori bacteria. The mice were injected with a neutralizing monoclonal antibody against IL-17 or an IgG isotype control at days 5, 8, and 11 postchallenge and sacrificed at day 14. Gastric mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR; the mean for the unimmunized control group treated with IgG isotype control antibody was set to 1 for each gene. The IFN-γ protein level was determined by cytometric bead array analysis of stomach saponin extracts. Pooled data from two independent experiments are shown as mean values for groups of 10 animals; error bars represent SEM. A significant difference in gene expression of immunized mice treated with anti-IL-17 or the isotype control, as assessed by Student's t test, is denoted by * (P < 0.05), ** (P < 0.01), or *** (P < 0.001).

We next studied how Th1-associated responses were influenced by IL-17 neutralization. Increases in the expression of CD4 (P < 0.01), the Th1 chemoattractant CXCL10 (P < 0.001), and CXCR3 (the CXCL10 receptor) (P < 0.05) were detected in mice treated with anti-IL-17 (Fig. 6). These results might represent an increased infiltration of Th1 cells to the stomach in these animals. In support of an amplified Th1 response, there was also an increased expression of IFN-γ, both mRNA (P < 0.01) and protein (P < 0.05), in the stomachs of IL-17-neutralized mice (Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

It is well documented that CD4+ T cells, in contrast to CD8+ T cells and B cells, are essential for vaccine-induced protection against H. pylori in mice (7). Here we have examined cytokines associated with CD4+ Th1 and/or Th17 responses and compared their contributions to vaccine-mediated protection. Our results demonstrate that increased expression levels of IL-12p40, TNF, IFN-γ, and IL-17 in the stomach correlate strongly with reduced H. pylori colonization. Although the upregulation of TNF, IFN-γ, and IL-17 in immunized mice coincides with vaccine-induced protection, our studies on in vivo neutralization of these cytokines clearly favor a function for IL-17 over IFN-γ and TNF in immune protection.

Our report is the first in which cytokine levels in the stomach have been shown to correlate with protection against H. pylori infection. Garhart et al. have previously demonstrated an association between increased expression of proinflammatory cytokine genes and vaccine-induced protection (9). In their study a quantitative correlation analysis of mRNA abundance in the stomach and H. pylori bacterial load was not possible, since the individual mice were broadly categorized as protected or nonprotected and the gene expression analysis was performed by conventional and not quantitative PCR. In our study, the strong correlation between enhanced IL-12p40, TNF, IFN-γ, and IL-17 gene expression and reduced bacterial load in the stomach was evident irrespective of antigens and immunization routes used, suggesting a common mechanism of immune protection against H. pylori infection.

Our study also clearly shows that a combination of immunization and challenge with H. pylori is necessary to enhance proinflammatory and protective immune responses in the stomach. Priming of the immune response to H. pylori antigens takes place in draining lymph nodes, i.e., cervicomandibular lymph nodes in the case of sublingual immunization (29) and mesenteric lymph nodes after intragastric immunization. Furthermore, activation of the endothelium after H. pylori infection (15, 29) would facilitate the migration of vaccine-induced lymphocytes from the lymph nodes to the stomach via the circulation. A study of volunteers orally vaccinated against cholera showed that H. pylori infection is necessary to attract vaccine-specific lymphocytes to the gastric mucosa (20). Immune cells induced by vaccination probably undergo further expansion in response to H. pylori components in the stomach, resulting in a local increase of proinflammatory cytokines as seen in our study. H. pylori infection in the stomach thus creates a milieu favoring and enhancing recruitment of vaccine-specific cells to the stomach and subsequent cytokine responses. The major source of TNF, IFN-γ, and IL-17 in immunized and infected mice is most likely infiltrating antigen-specific CD4+ T cells, whereas antigen-presenting cells (APC), after interaction with CD4+ T cells at the effector site, may account for the subsequent upregulation of IL-12p40. An alternative early source of IL-17 might also be innate lymphoid cells (5, 38). The innate IL-17-producing cells include γδ T cells, which have been shown to be increased in the gastric mucosae of patients with severe H. pylori gastritis (8).

The strong upregulation of TNF, IL-12p40, IFN-γ, and IL-17, cytokines associated with Th1 and/or Th17 responses, in immunized and H. pylori-infected mice seen in our study indicates an ability to mount gastric immune responses of both the Th1 and Th17 types concurrently in these animals. Elevated levels of these cytokines in the stomach mucosae of H. pylori-infected patients have also been reported (12, 18, 19). Although reciprocal inhibition between Th1 and Th17 cells has been reported (11, 22), a simultaneous induction of Th1 and Th17 responses is necessary under certain circumstances for either of the cell populations to exert its functions. For instance, in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis, autoreactive Th17 cells have been shown to be dependent on Th1 cells to enter the central nervous system (24), while conversely, protective Th1 responses induced by Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination have been shown to be dependent on the presence of memory Th17 cells (14). There is also the possibility that IFN-γ and IL-17, the signature cytokines of Th1 and Th17 responses, respectively, are produced by the same cells in the stomach mucosa, since such a subpopulation of T cells has been observed in both mice and humans (1, 37).

To our knowledge, the current study is the first where the contributions of both IL-17 and IFN-γ to protection against H. pylori have been addressed. In agreement with earlier reports, we found IL-17 to be of importance for vaccine-induced protection (6, 41). Our study shows that IL-17 neutralization results in an increase in H. pylori colonization, both in immunized and in unimmunized infected mice. This is in contrast to the decreased H. pylori colonization recently observed in unimmunized IL-17−/− mice (34, 35). Apart from the different challenge strains used, the increased contribution of compensatory protective mechanisms in knockout mice compared to animals treated with neutralizing antibodies postchallenge might explain the discrepancy in the results. IFN-γ has also, based on experiments conducted with knockout mice, been suggested to play a role in immune protection against H. pylori infection (3, 33); such a role for IFN-γ could not be validated in our study by neutralizing the cytokine during the effector phase. It should be noted, however, that studies using IFN-γ−/− mice have generated conflicting data with regard to the role of IFN-γ in vaccine-induced protection against H. pylori (3, 9, 31-33). Protection in immunized mice has been shown in the different studies to be totally, partially, or not dependent on IFN-γ, which is puzzling since identical or very similar animal models were used. In addition, the in vivo neutralization of IL-17 in the present study tends to further question IFN-γ as a key player in protection against H. pylori infection, since the ability to fight the infection was significantly dampened in these animals even though the local Th1 response was enhanced. However, this does not rule out the possibility that IFN-γ responses are needed during the priming and/or early effector phase in order to achieve efficient Th17 responses that eventually lead to reduction of H. pylori burden.

In conclusion, although a strong correlation between protection against H. pylori infection and enhanced expression of several proinflammatory cytokines locally in the stomach was seen, our study specifically identifies IL-17 as a crucial effector cytokine for the vaccine-induced immune responses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation and the Swedish Research Council (Medicine) (project K2000-06X-03382). The Mucosal Immunobiology and Vaccine Center (MIVAC) at the University of Gothenburg is supported by The Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research.

We thank Barbara Matsuoka, Sylvia Kwan, and Janet Wagner (MRL, PA) for their expert assistance in purification of the anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibody.

Editor: R. P. Morrison

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acosta-Rodriguez, E. V., et al. 2007. Surface phenotype and antigenic specificity of human interleukin 17-producing T helper memory cells. Nat. Immunol. 8:639-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aebischer, T., et al. 2008. A vaccine against Helicobacter pylori: towards understanding the mechanism of protection. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 298:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akhiani, A. A., et al. 2002. Protection against Helicobacter pylori infection following immunization is IL-12-dependent and mediated by Th1 cells. J. Immunol. 169:6977-6984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akhiani, A. A., K. Schon, and N. Lycke. 2004. Vaccine-induced immunity against Helicobacter pylori infection is impaired in IL-18-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 173:3348-3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buonocore, S., et al. 2010. Innate lymphoid cells drive interleukin-23-dependent innate intestinal pathology. Nature 464:1371-1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLyria, E. S., R. W. Redline, and T. G. Blanchard. 2009. Vaccination of mice against H. pylori induces a strong Th-17 response and immunity that is neutrophil dependent. Gastroenterology 136:247-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ermak, T. H., et al. 1998. Immunization of mice with urease vaccine affords protection against Helicobacter pylori infection in the absence of antibodies and is mediated by MHC class II-restricted responses. J. Exp. Med. 188:2277-2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Futagami, S., et al. 2006. γδ T cells increase with gastric mucosal interleukin (IL)-7, IL-1β, and Helicobacter pylori urease specific immunoglobulin levels via CCR2 upregulation in Helicobacter pylori gastritis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21:32-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garhart, C. A., F. P. Heinzel, S. J. Czinn, and J. G. Nedrud. 2003. Vaccine-induced reduction of Helicobacter pylori colonization in mice is interleukin-12 dependent but gamma interferon and inducible nitric oxide synthase independent. Infect. Immun. 71:910-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garhart, C. A., R. W. Redline, J. G. Nedrud, and S. J. Czinn. 2002. Clearance of Helicobacter pylori infection and resolution of postimmunization gastritis in a kinetic study of prophylactically immunized mice. Infect. Immun. 70:3529-3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrington, L. E., et al. 2005. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat. Immunol. 6:1123-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karttunen, R., T. Karttunen, H. P. Ekre, and T. T. MacDonald. 1995. Interferon gamma and interleukin 4 secreting cells in the gastric antrum in Helicobacter pylori positive and negative gastritis. Gut 36:341-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasuga-Aoki, H., et al. 1999. Tumour necrosis factor and interferon-γ are required in host resistance against virulent Rhodococcus equi infection in mice: cytokine production depends on the virulence levels of R. equi. Immunology 96:122-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khader, S. A., et al. 2007. IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4+ T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat. Immunol. 8:369-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi, M., et al. 2004. Induction of peripheral lymph node addressin in human gastric mucosa infected by Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:17807-17812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komiyama, Y., et al. 2006. IL-17 plays an important role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 177:566-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kusters, J. G., A. H. van Vliet, and E. J. Kuipers. 2006. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19:449-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindholm, C., M. Quiding-Jarbrink, H. Lonroth, A. Hamlet, and A. M. Svennerholm. 1998. Local cytokine response in Helicobacter pylori-infected subjects. Infect. Immun. 66:5964-5971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luzza, F., et al. 2000. Up-regulation of IL-17 is associated with bioactive IL-8 expression in Helicobacter pylori-infected human gastric mucosa. J. Immunol. 165:5332-5337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattsson, A., H. Lonroth, M. Quiding-Jarbrink, and A. M. Svennerholm. 1998. Induction of B cell responses in the stomach of Helicobacter pylori-infected subjects after oral cholera vaccination. J. Clin. Invest. 102:51-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moorchung, N., et al. 2006. The role of mast cells and eosinophils in chronic gastritis. Clin. Exp. Med. 6:107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakae, S., Y. Iwakura, H. Suto, and S. J. Galli. 2007. Phenotypic differences between Th1 and Th17 cells and negative regulation of Th1 cell differentiation by IL-17. J. Leukoc. Biol. 81:1258-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niv, Y., and R. Hazazi. 2008. Helicobacter pylori recurrence in developed and developing countries: meta-analysis of 13C-urea breath test follow-up after eradication. Helicobacter 13:56-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Connor, R. A., et al. 2008. Th1 cells facilitate the entry of Th17 cells to the central nervous system during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 181:3750-3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogawa, A., A. Andoh, Y. Araki, T. Bamba, and Y. Fujiyama. 2004. Neutralization of interleukin-17 aggravates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Clin. Immunol. 110:55-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pappo, J., et al. 1999. Helicobacter pylori infection in immunized mice lacking major histocompatibility complex class I and class II functions. Infect. Immun. 67:337-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plessner, H. L., et al. 2007. Neutralization of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) by antibody but not TNF receptor fusion molecule exacerbates chronic murine tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 195:1643-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raghavan, S., M. Hjulstrom, J. Holmgren, and A. M. Svennerholm. 2002. Protection against experimental Helicobacter pylori infection after immunization with inactivated H. pylori whole-cell vaccines. Infect. Immun. 70:6383-6388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raghavan, S., et al. 2010. Sublingual immunization protects against Helicobacter pylori infection and induces T and B cell responses in the stomach. Infect. Immun. 78:4251-4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raghavan, S., A. M. Svennerholm, and J. Holmgren. 2002. Effects of oral vaccination and immunomodulation by cholera toxin on experimental Helicobacter pylori infection, reinfection, and gastritis. Infect. Immun. 70:4621-4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawai, N., et al. 1999. Role of gamma interferon in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammatory responses in a mouse model. Infect. Immun. 67:279-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sayi, A., et al. 2009. The CD4+ T cell-mediated IFN-γ response to Helicobacter infection is essential for clearance and determines gastric cancer risk. J. Immunol. 182:7085-7101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi, T., W. Z. Liu, F. Gao, G. Y. Shi, and S. D. Xiao. 2005. Intranasal CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide is a potent adjuvant of vaccine against Helicobacter pylori, and T helper 1 type response and interferon-γ correlate with the protection. Helicobacter 10:71-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi, Y., et al. 2010. Helicobacter pylori-induced Th17 responses modulate Th1 cell responses, benefit bacterial growth, and contribute to pathology in mice. J. Immunol. 184:5121-5129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiomi, S., et al. 2008. IL-17 is involved in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammatory responses in a mouse model. Helicobacter 13:518-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suerbaum, S., and P. Michetti. 2002. Helicobacter pylori infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:1175-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suryani, S., and I. Sutton. 2007. An interferon-γ-producing Th1 subset is the major source of IL-17 in experimental autoimmune encephalitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 183:96-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutton, C. E., et al. 2009. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from γδ T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity 31:331-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutton, P., et al. 2007. Effectiveness of vaccination with recombinant HpaA from Helicobacter pylori is influenced by host genetic background. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 50:213-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Svennerholm, A. M., and A. Lundgren. 2007. Progress in vaccine development against Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 50:146-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Velin, D., et al. 2009. Interleukin-17 is a critical mediator of vaccine-induced reduction of Helicobacter infection in the mouse model. Gastroenterology 136:2237-2246 e2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamamoto, T., et al. 2004. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma in Helicobacter pylori infection. Microbiol. Immunol. 48:647-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]