Abstract

Moraxella catarrhalis is subjected to oxidative stress from both internal and environmental sources. A previous study (C. D. Pericone, K. Overweg, P. W. Hermans, and J. N. Weiser, Infect. Immun. 68:3990-3997, 2000) indicated that a wild-type strain of M. catarrhalis was very resistant to killing by exogenous hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). The gene encoding OxyR, a LysR family transcriptional regulator, was identified and inactivated in M. catarrhalis strain O35E, resulting in an increase in sensitivity to killing by H2O2 in disk diffusion assays and a concomitant aerobic serial dilution effect. Genes encoding a predicted catalase (KatA) and an alkyl hydroperoxidase (AhpCF) showed dose-dependent upregulation in wild-type cells exposed to H2O2. DNA microarray and real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analyses identified M. catarrhalis genes whose expression was affected by oxidative stress in an OxyR-dependent manner. Testing of M. catarrhalis O35E katA and ahpC mutants for their abilities to scavenge exogenous H2O2 showed that the KatA catalase was responsible for most of this activity in the wild-type parent strain. The introduction of the same mutations into M. catarrhalis strain ETSU-4 showed that the growth of a ETSU-4 katA mutant was markedly inhibited by the addition of 50 mM H2O2 but that this mutant could still form a biofilm equivalent to that produced by its wild-type parent strain.

Moraxella catarrhalis is an aerobic, Gram-negative coccobacillus that has been shown to be an important cause both of otitis media (i.e., middle ear disease) in infants and young children and of infectious exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in adults (18, 31, 46). The mucosa of the human nasopharynx is the niche normally colonized by M. catarrhalis. This colonization event provides M. catarrhalis with a foothold in the human body from which it can spread to other anatomic sites (i.e., the middle ear and lower respiratory tract) but also exposes this bacterium to negative selective pressures exerted both by the host (25, 32) and by the normal flora of the nasopharynx (38, 55). Among these, oxidative stress is a formidable obstacle both to initial colonization and to persistence in the respiratory tract (for reviews, see references 15 and 52).

While there are different types of reactive oxygen species (e.g., H2O2, O2−, peroxynitrite) that can cause oxidative stress (15, 29), the ability of bacterial pathogens to resist killing by H2O2 has been the subject of considerable attention for some years. The mechanisms by which H2O2 can kill bacteria include, but are not limited to, damage to proteins and DNA related to the Fenton reaction, peroxidation of membrane lipids, and oxidation of iron-sulfur clusters in proteins (15). The biologically relevant sources of H2O2 include phagocytic cells (40, 41), some members of the normal flora of the host (38, 54), and endogenous production by the bacterium itself during aerobic growth (i.e., from sources outside the bacterial respiratory chain) (44; for a review, see reference 15).

The ability of bacteria to respond to the presence of H2O2 and to increase their resistance to killing by this compound through the induction or upregulation of antioxidant proteins was first studied in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (6, 30) and then in Escherichia coli (58) more than 2 decades ago. These studies included the identification of OxyR as a LysR-like positive regulatory element that controlled the expression of some of these H2O2-inducible genes (6). The genes positively controlled by OxyR in E. coli include those encoding a catalase (katG), an alkyl hydroperoxide reductase system (ahpCF), glutathione reductase (gorA), glutaredoxin (grxA), and thioredoxin (trxC) (50). E. coli OxyR can exist in either an oxidized or a reduced state and can form an intramolecular disulfide bond between C199 and C208 that is eliminated (by reduction) when the source of oxidative stress is removed. While both the oxidized and the reduced forms of OxyR have DNA binding activity, the oxidized form of OxyR typically functions as a transcriptional activator in E. coli. In other bacteria, including Neisseria gonorrhoeae (56) and Pseudomonas putida (12), however, OxyR can function as a repressor for some target genes. Mutants lacking the ability to express OxyR are usually more susceptible to killing by H2O2 than are their wild-type parent strains (6, 11, 27), but there are exceptions to this rule (e.g., N. gonorrhoeae [56]).

Most previous studies on the interaction of M. catarrhalis with other bacteria that can colonize the mucosa of the human upper respiratory tract focused mainly on various alpha-hemolytic streptococci and their ability to affect either the growth or the viability of M. catarrhalis strains in vitro (4, 38, 54, 55). Two of these studies focused on the inhibitory effect of H2O2 produced by these streptococci (38, 54). One study showed that a wild-type M. catarrhalis strain was much more resistant to killing by exogenous H2O2 than the other bacteria tested (38), and another suggested that M. catarrhalis could somehow increase its resistance to killing by what was presumed to be H2O2 (55). In the present study, inactivation of the M. catarrhalis oxyR gene was shown to increase the sensitivity of this organism to killing by H2O2. DNA microarray analysis of M. catarrhalis gene products whose expression was upregulated under conditions of oxidative stress identified several genes encoding antioxidant proteins, including KatA and AhpCF. Inactivation of these different genes revealed that expression of the M. catarrhalis KatA catalase was essential for effective resistance to killing by exogenous H2O2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. M. catarrhalis strains were grown using brain heart infusion (BHI)-based broth (Difco/Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) or BHI agar (2); these media were supplemented with spectinomycin (15 μg/ml) or kanamycin (15 μg/ml) when appropriate. Escherichia coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium as described previously (42).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| M. catarrhalis | ||

| O35E | Wild-type disease isolate | 57 |

| O35EΔoxyR | oxyR deletion mutant; Kanr | This study |

| O35EΔoxyR (repaired) | ΔoxyR deletion mutant with wild-type oxyR gene | This study |

| O35EΔkatA | katA deletion mutant; Kanr | This study |

| O35EΔahpC | ahpC deletion mutant; Kanr | This study |

| ETSU-4 | Wild-type disease isolate | Steven Berk |

| ETSU-4ΔoxyR | oxyR deletion mutant; Kanr | This study |

| ETSU-4ΔkatA | katA deletion mutant; Kanr | This study |

| ETSU-4ΔahpC | ahpC deletion mutant; Kanr | This study |

| ETSU-9 | Wild-type disease isolate | Steven Berk |

| V1120 | Nasopharyngeal isolate | Frederick Henderson |

| 7169 | Wild-type disease isolate | 26 |

| ATCC 43617 | Wild-type disease isolate | American Type Culture Collection |

| E. coli M15(pREP4) | Host for pPROEX HTb-derived plasmids | Qiagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pWW115 | M. catarrhalis cloning vector; Specr Chlorr | 59 |

| pWL01 | pWW115 containing the M. catarrhalis O35E oxyR gene; Specr | This study |

| pTH61-1 | pWW115 containing the M. catarrhalis O35E katA gene; Specr | This study |

| pWL100E-KanC | Derivative of pACYC177 containing a nonpolar kanamycin resistance cartridge | 19 |

| pPROEX Htb | 6×His expression vector; Ampr | Invitrogen |

| pHIS-OxyR | pPROEX HTb expressing M. catarrhalis O35E OxyR; Ampr | This study |

Construction of M. catarrhalis oxyR, ahpC, and katA deletion mutants.

The overlapping extension PCR mixture (13) for each mutagenesis construct contained 3 separate amplicons mixed in equal amounts. For amplicon A, the primers (Table 2) were 162-p4 and 162-p3 (oxyR), TH287 and TH288 (ahpC), and katAP1 and katAP2 (katA). Amplicon B was the same for all three constructs and consisted of the nonpolar kan cartridge and its promoter as amplified from pWL100E-KanC (19) with primers KanPro-5′ and NPK3-3′. For amplicon C, the primers were 162-p2 and 162-p1 (oxyR), TH289 and TH286 (ahpC), and katAP3 and katAP4 (katA). The final overlapping extension PCR mixture contained equal amounts of amplicons A, B, and C together with the following primer pairs: 162-p4 and 162-p1 (oxyR), TH287 and TH286 (ahpC), and katAP1 and katAP4 (katA). The final amplicons were used to transform M. catarrhalis O35E via a plate-based transformation method (36). Kanamycin-resistant mutants were selected, and nucleotide sequence analysis confirmed the deletion of the oxyR, ahpC, or katA gene, respectively. The same strategy was utilized to generate oxyR and ahpC mutations in M. catarrhalis ETSU-4. The katA deletion mutant constructed in M. catarrhalis ETSU-4 required the usage of primers EU4KATAP3-1 and EU4KATAP4 for the generation of amplicon C.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers utilized in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| TH286 | GATACTAAAATCAGCCCACGCA |

| TH287 | GGATATGTTCATCATTTTTCA |

| TH288 | GGTCGACGGATCCGGGGGTATTTGATTATACACCATAAA |

| TH289 | TGGAGGGAATAATGCGACCCAAGCCAAGCTTGGATTTGGTA |

| kanPro-5′ | CCCCGGATCCGTCGACC |

| NPK3-3′ | GGGTCGCATTATTCCCTCCA |

| TH284 | ACGCGGATCCACTTTAATGGCGATGATGTa |

| TH285 | ACGCGGATCCCTGCACCAGAAGATTGTGAa |

| 162-p1 | TCACGCACATACTGAGCTGC |

| 162-p2 | AGGTCGACGGATCCGGGGTTGGCGTAGTGTGATCAT |

| 162-p3 | GAGGGAATAATGCGACCCCAAGCACTTGCATCCTCA |

| 162-P4 | ATCCATCAAGAAATACTCCAA |

| 162comp-5B | ATCGGATCCCATGAACTGTGTCATCTGa |

| 162comp-3B | CAGGATCCGATTAATAATTGCTGCCAa |

| HIS162-B5′ | ATCGGATCCATGATCACACTACGCCAAa |

| HIS162-B3′ | ATCGAAGCTTTTATGCTTCATTTTCTGAGGb |

| katAP1 | CGATGCTGATGCTAACAGGC |

| katAP2 | AGGTCGACGGATCCGGGGAGGGCATTTCATTTCACTCAT |

| katAP3 | GAGGGAATAATGCGACCCGCGTATGAGAGCGACCCT |

| katAP4 | AACCAGGCGATAAGATTACCG |

| EU4katAP3-1 | GAGGGAATAATGCGACCCGACCCTGCTCGCCAT |

| EU4katAP4 | TGTCATCTTATGTATTCAGCC |

| 1139rt1 | CCCACGCTGTCCTGTGTACTC |

| 1139rt2 | ACCGCCATAGTTATCGCCC |

| 163rt1 | GCGTCACCAGCCATTGGTA |

| 163rt2 | AAGCCACGAGTGATTTTGCC |

| 323fw | AAGAAGCCCAAGTGGCTGC |

| 323rv | CCATGATTGCCTGCTTTTTTG |

| 164fw | TCGTGAACTTATGACCAAACTCAAA |

| 164rv | AGGTGACGGGATCTTTTTCAAA |

| 880fw | GGGCTACAGCTACGATGCACT |

| 880rv | ATGGTGGCGTGAATGGTGA |

| 2fw | AACATGGTTGCCCCTGGTAC |

| 2rv | GCAGCATATCCCATTGCAAAA |

| 1249fw | CCAATCAATCTAACCGCCATG |

| 1249rv | GACCAAATTGAGCCAGTAAAGTCA |

| 400fw | CCGATACCAATGTGGATGCA |

| 400rv | GGGCGAGTGAATTTGTAAGCA |

| 1202fw | TGCCAAAATTGCCTATAAAACAAC |

| 1202rv | TCGTTACTATCATTTGGAATGATTGC |

| 425fw | CTGGAAGCGTGAGCCACAC |

| 425rv | GGTAAAGCGTGCATTGGCA |

| 1579fw | TTGGTTTATGGTGGTGGCAAT |

| 1579rv | CTTTTTCCACCATGTGCGATG |

| 1398fw | GTTAAGCCTGCCGCTGTCA |

| 1398rv | TTTTGGGAGCAGGGACGAC |

| 142fw | ACAGTGATAGCGGCCATTGTT |

| 142rv | CTGTTTTTGAGCATAGTTCACAGGTAC |

| 516fw | ACCCAGATTTGACACTGCCAG |

| 516rv | AAGGTCGTGCCTGAACCGT |

| 701fw | CGTTGTGCCAGGCATGC |

| 701rv | CGTGAGCTTCTTGCCCAAA |

| 165rt1 | ACACTGCGATGGCCCATTT |

| 165rt2 | CGCCTCAACACCTGAGTTACC |

| 1128fw | GAATTGATGGGCGTCTCTGC |

| 1128rv | AAAGGGATAAGCCCAGTGCTG |

| 1373fw | TTAGCAGCACAGGGCGAAG |

| 1373rv | GCTTGCTCAAACTGGGTCAAA |

| 1452rt3 | GCCTACTTTGGGTGAGCGTG |

| 1452rt4 | GGTAATTGGTGTACCGCCCTC |

| 903fw | TGCCTTATTGGATTTGGCTGT |

| 903rv | GGCGTTTGGCAATGTCTGA |

Underlining indicates a BamHI restriction site.

Underlining indicates a HindIII restriction site.

Repair of the oxyR mutation.

Primers 162-P1 and 162-P4 were used to PCR amplify a 2.3-kb fragment comprising the wild-type O35E oxyR open reading frame (ORF) together with ∼0.7 kb of both the upstream and downstream flanking regions. The amplicon was utilized to transform the O35EΔoxyR mutant. The repaired strain containing the wild-type oxyR gene was confirmed by nucleotide sequence analysis and was designated O35EΔoxyR (repaired).

Complementation of the oxyR and katA mutations.

Primers 162comp-3B and 162comp-5B were used to PCR amplify a 1.3-kb fragment of O35E chromosomal DNA containing the oxyR ORF and some flanking DNA. This amplicon was ligated into the BamHI site of the M. catarrhalis cloning vector pWW115 (59) and was used for the transformation of M. catarrhalis O35EΔoxyR. The recombinant plasmid containing the M. catarrhalis O35E oxyR ORF was designated pWL01. The wild-type katA gene from M. catarrhalis strain O35E was amplified with primers TH284 and TH285, ligated into pWW115, and used to transform M. catarrhalis O35EΔkatA so as to yield pTH61-1. The latter plasmid was also used to transform M. catarrhalis ETSU-4ΔkatA.

Determination of the MBC of H2O2 for M. catarrhalis.

Minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC) were determined by using a modification of the method described by Weiser and colleagues (38). Portions (1.0 ml) of mid-logarithmic-phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], ∼0.7) cultures were transferred to a 24-well polystyrene tissue culture plate, and H2O2 (8.8 M; Fisher Scientific) was added to each well to achieve the range of desired final concentrations. The suspension was incubated at 37°C for 15 min without shaking, and then the contents of the wells were serially diluted and plated onto BHI agar. The MBC was defined as the concentration of H2O2 required to cause at least a 99.9% reduction in the number of viable bacteria relative to the number for a control in which water was used instead of H2O2.

Disk diffusion assays.

Bacterial cells grown to mid-logarithmic phase (OD600, 0.7) were added (at a 1:1,000 ratio) to 25 ml of molten 1.5% (wt/vol) BHI agar at 45°C. This suspension was gently mixed with agitation for 30 s; then a 10-ml portion of this mixture was added on top of 20 ml of solidified BHI agar and was allowed to cool until solidified. A sterile disk (diameter, 6 mm) cut from thin chromatography paper was saturated with 10 μl of 88 mM H2O2 and was then applied to the top of the solidified agar. The final size of the zone of growth inhibition around each disk represents the mean of four axial measurements for each disk.

Use of growth curves to assess the response to exogenous H2O2.

M. catarrhalis strains ETSU-4, ETSU-4ΔoxyR, ETSU-4ΔkatA, ETSU-4ΔkatA(pTH61-1), ETSU-4ΔkatA(pWW115), and ETSU-4ΔahpC were grown in BHI broth to mid-logarithmic phase (OD600, 0.7). H2O2 was then added to a final concentration of 50 mM; the flask was incubated at 37°C with agitation; and turbidity measurements (OD600) were recorded over time.

Purification of a recombinant M. catarrhalis OxyR protein.

Primers HIS-162B5′ and HIS-162B3′ were used to PCR amplify the oxyR coding region from M. catarrhalis O35E genomic DNA. This amplicon was sequentially digested with BamHI and HindIII (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and was then ligated into the pPROEX HTb vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The reaction mixture was used to transform electrocompetent E. coli M15 cells, and transformants containing the oxyR gene were selected on LB agar containing ampicillin. The plasmid was designated pHIS-OxyR. The His-tagged OxyR protein was purified from sonicated lysates (cells induced according to the manufacturer's instructions) using Ni2+-chelate chromatography. This purified recombinant protein was used by Rockland Immunochemicals (Boyertown, PA) to develop a polyclonal rat OxyR antiserum. Western blot analysis was performed as described elsewhere using appropriate secondary antibodies (22).

Evaluation of the ability of M. catarrhalis O35EΔoxyR to form isolated colonies.

Strains O35E and O35EΔoxyR were grown to mid-logarithmic phase and were then serially diluted in BHI broth. A 2-μl portion of each dilution was spotted onto BHI agar alone or onto BHI agar containing bovine liver catalase (200 U/ml agar; Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ), and these plates were incubated overnight.

H2O2 scavenging assay.

The Amplex Red hydrogen peroxide/peroxidase assay kit (Invitrogen) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions to measure the rate of H2O2 degradation by bacterial cells. The standard assay mixture contained 25 μl of broth-grown bacterial cells (approximately 1.6 × 107 CFU per well), 25 μl of 40 μM H2O2 (final concentration, 10 μM), and 50 μl of the horseradish peroxidase-Amplex Red solution. Fluorescence was measured after 1 min by using an excitation wavelength of 530 nm and an emission wavelength of 595 nm in a SpectraFluor Plus microplate reader (Tecan, Research Triangle Park, NC).

RNA isolation for DNA microarray and real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analyses.

Bacterial cells were grown in BHI at 37°C with agitation to an OD600 of 0.7. A portion of this culture was diluted 1:100 in fresh BHI, and 2-ml portions of this suspension were added to each of four wells in a 24-well tissue culture plate (Corning, Corning, NY). The tissue culture plate was then placed at 37°C under an atmosphere of 95% air-5% CO2 without agitation for 19 h. After 19 h, H2O2 was added to a final concentration of 50 mM. The contents of each well were mixed and allowed to incubate at 37°C under 95% air-5% CO2 without agitation for 15 min. Total RNA was extracted from these cells with the RiboPure Bacteria kit (Ambion, Woodlands, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA samples were treated with DNase I by use of a Message Clean kit (GenHunter Corp., Nashville, TN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The integrity of the RNA samples was measured with the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). For the DNA microarray experiments involving (i) analysis of the M. catarrhalis O35E response to H2O2 and (ii) the evaluation of M. catarrhalis O35E versus M. catarrhalis O35EΔoxyR in the presence of 50 mM H2O2, three independent experiments and accompanying RNA isolations were performed.

cDNA preparation, DNA microarray hybridization, and data analysis.

cDNA was prepared by a method similar to that described previously (60). Briefly, 5 μg of each of the RNA samples mentioned above was mixed with 3 μg of M. catarrhalis genome-directed primers (60). The individual cDNA samples were labeled with either Cy3-dCTP or Cy5-dCTP as described previously (22). The M. catarrhalis DNA microarrays utilized in this study have been described previously (60). Equivalent amounts of the Cy3- and Cy5-labeled cDNAs were mixed thoroughly and were hybridized to the M. catarrhalis DNA microarray slides as described previously (60). After hybridization, the slides were washed, dried, and scanned as described previously (22). For both sets of conditions described immediately above, one “dye swap” experiment was performed. The Acuity 4.0 software package (Molecular Devices) was used to analyze the microarray data as described previously (22). To identify genes that exhibited altered expression profiles in the presence of H2O2, a threshold of 2-fold increased or decreased expression relative to expression by nonexposed cells was utilized. The gene of interest had to demonstrate the altered expression profile in at least three of the four microarray analyses, and the P value for the difference had to be ≤0.05 as calculated by the one-sample t test.

Real-time RT-PCR.

Oligonucleotide primer pairs were designed for use in real-time RT-PCR (Table 2) with PrimerExpress software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time RT-PCRs were prepared as described previously (60), and one-step relative real-time RT-PCR was performed on these samples utilizing the 7500 Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). DNA contamination and the presence of “primer dimers” were assessed as described previously (60). All of the relative real-time RT-PCR experiments involved the use of at least two independently isolated RNA samples. The endogenous control was MC1452, encoding a predicted gyrase B (60). The results were analyzed (by the ΔΔCT method) with Relative Quantification Study software (Applied Biosystems).

Crystal violet-based assay for biofilm measurements.

M. catarrhalis strains were evaluated for their abilities to form biofilms under in vitro conditions by utilizing a method adapted from that previously described (35). Briefly, M. catarrhalis cells were grown in BHI broth to an OD600 of 0.7. A 2-ml portion of this bacterial suspension was used to inoculate a 24-well tissue culture plate in triplicate. The tissue culture plate was incubated at 37°C in a 95% air-5% CO2 incubator for 24 h. The plate was then stained with crystal violet to detect biofilm formation as previously described (35).

Microarray data accession numbers.

The raw data from the DNA microarray experiments performed in this study have been deposited at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession numbers GSE24331 and GSE24351.

RESULTS

Sensitivities of wild-type M. catarrhalis strains to killing by H2O2.

A previous study that focused on the ability of Streptococcus pneumoniae to inhibit the growth of pathogens that colonize the upper respiratory tract indicated that a strain of M. catarrhalis (i.e., Bc1) was markedly more resistant to killing by H2O2 than were the other bacterial species tested (38). Using an assay similar to that described previously (38), the MBC of H2O2 for M. catarrhalis O35E was shown to be between 400 and 500 mM (data not shown). Subsequent testing of three additional wild-type M. catarrhalis strains (7169, V1120, and ETSU-4) in a disk diffusion-based system indicated that all three of these strains had essentially the same level of resistance to killing by H2O2 as O35E (data not shown). It was also determined that freshly prepared and filter-sterilized BHI medium was required in order to obtain reproducible and accurate results in these and all subsequent experiments.

Identification of the M. catarrhalis oxyR gene.

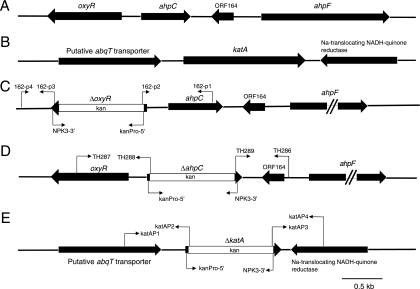

In other Gram-negative pathogens that can colonize the upper respiratory tract, including nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (9) and Neisseria meningitidis (14), the OxyR protein has been shown to be a global regulator of the oxidative stress response. Inspection of the nucleotide sequence of the genome of M. catarrhalis ATCC 43617 (60) indicated that MC162 encoded a LysR family transcriptional regulator that had been annotated as an OxyR protein in several different bacterial species. Located on the opposite strand (Fig. 1A) were two other ORFs (ahpC and ahpF) encoding a predicted peroxidase (AhpC) and its cognate flavoprotein disulfide reductase (AhpF). AhpF functions to reduce the AhpC protein, which can degrade both H2O2 and organic peroxides (for a review, see reference 39). Nucleotide sequence analysis of the oxyR ORF from four additional M. catarrhalis strains (i.e., O35E, ETSU-9, 7169, and ETSU-4) indicated that the oxyR genes in these strains were identical except for a single nucleotide change (G238A) in the ETSU-4 and ETSU-9 oxyR genes (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the M. catarrhalis oxyR, ahpC, ahpF, and katA loci in wild-type and mutant strains. (A) The oxyR, ahpC, and ahpF genes in wild-type M. catarrhalis O35E; (B) the katA locus in wild-type M. catarrhalis O35E; (C) the M. catarrhalis O35EΔoxyR mutant; (D) the O35EΔahpC mutant; (E) the O35EΔkatA mutant. Bent arrows represent relevant oligonucleotide primers.

Structure of the M. catarrhalis OxyR protein.

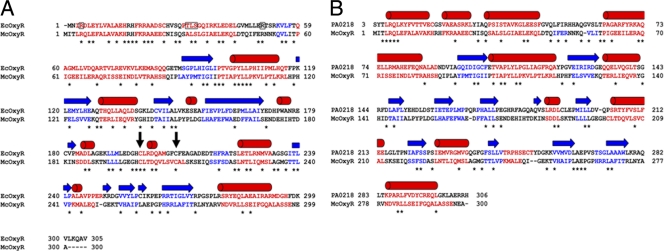

When a simple BLAST search (1) was limited to the E. coli genome, the E. coli OxyR protein was found to be fairly homologous to the M. catarrhalis OxyR protein (E value, 2 × 10−41). Alignment of these two sequences showed that these proteins share approximately 30% identity (Fig. 2A). There are two cysteine residues (C199 and C208 in E. coli OxyR) that are critical for the function of the protein. These two cysteines (C200 and C209 in M. catarrhalis OxyR) are conserved between these two proteins. The homology between these proteins is particularly pronounced in the N-terminal putative DNA-binding domain (Fig. 2A). In E. coli OxyR, residues T31, L32, and S33 have been shown to be important for DNA binding (21). The latter two residues are identical in the M. catarrhalis protein: L34 and S35. It is not known whether this implies that the M. catarrhalis protein binds to similar DNA targets or that these residues are important for the conformation of the N-terminal domain. Given the high overall sequence identity and the conservation of the critical cysteines, it is very likely that M. catarrhalis OxyR shares structure and function with E. coli OxyR (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Indeed, the structure is likely to be similar to that of the entire LysR family of proteins.

FIG. 2.

Structure-based sequence alignment of M. catarrhalis OxyR with OxyR proteins from both E. coli and P. aeruginosa. The numbering is given on each side of the sequences. Areas of predicted helices are shown in red, while areas of predicted β-strands are blue. (A) The secondary structural elements of E. coli OxyR, as assigned by DSSP (17) from PDB entry 1I69, are shown above the sequences as red cylinders (helices) and blue arrows (β-strands). Areas of identity between the two structures are marked with asterisks. Where no structural information is available, predictions from a separate PSIPRED (16) prediction are shown in the color code described above. Clustal W (23) was used for the DNA-binding domain alignment. PROMALS3D (37) was used for the remainder of the alignment. Residues shown to be important for DNA binding in E. coli OxyR are boxed. The vertical black arrows indicate the conserved cysteine residues critical to the function of E. coli OxyR. (B) Alignment with the PA0218 OxyR protein. PROMALS3D (37) was used for the entire alignment. All coloring and notation conventions are the same as for panel A.

No crystal structure is available for any full-length OxyR protein. Therefore, a hidden Markov model search (48, 49) was performed against the Protein Data Bank (PDB) for proteins of known structure that are similar in sequence to M. catarrhalis OxyR. A cluster of proteins was found with nearly identical statistics (match probability, 100%; E value, 0.0). M. catarrhalis OxyR was compared to the PA0218 protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (unpublished; PDB accession code 3FZV). A sequence alignment demonstrates that the proteins share approximately 21% sequence identity, with no major insertions or deletions (Fig. 2B). The N-terminal, DNA-binding domain is dominated by four α-helices (Fig. 2B), the third of which harbors residues critical for DNA binding. The C-terminal domain adopts a fold similar to that of E. coli OxyR (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). It should be noted that the relative positions of the DNA-binding domain and the regulatory domain for M. catarrhalis OxyR could be different from those shown here.

Construction and characterization of an M. catarrhalis oxyR mutant.

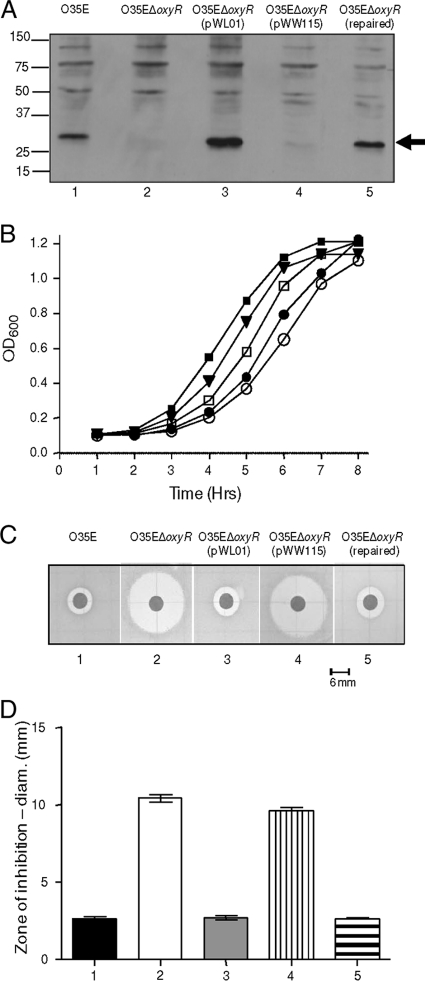

The majority of the M. catarrhalis O35E oxyR ORF was deleted and replaced with a kanamycin resistance cassette (Fig. 1C) as described in Materials and Methods. This oxyR mutant did not express any detectable OxyR protein as determined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3 A, lane 2). When grown in BHI broth, this oxyR mutant had a longer lag phase than its wild-type parent strain (Fig. 3B). Provision of a wild-type oxyR gene in trans in this oxyR mutant resulted in relatively high level expression of OxyR (Fig. 3A, lane 3), but this large amount of OxyR protein did not completely eliminate the mutant's growth defect (Fig. 3B). This inability of pWL01 to restore wild-type growth characteristics to the oxyR mutant may have been the result of the presence of the pWW115 plasmid backbone, because the presence of this vector alone in the oxyR mutant resulted in a slightly greater growth defect than that observed with the mutant alone (Fig. 3B). Alternatively, overexpression of OxyR may have had a negative effect on the growth profile. Replacement (i.e., repair) of the mutated oxyR gene with a wild-type oxyR gene resulted in wild-type expression of OxyR (Fig. 3A, lane 5) and a growth phenotype very similar to that of the wild-type parent strain (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Characterization of the M. catarrhalis O35EΔoxyR mutant and related strains. (A) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates of M. catarrhalis O35E (lane 1), O35EΔoxyR (lane 2), O35EΔoxyR(pWL01) (lane 3), O35EΔoxyR(pWW115) (lane 4), and O35EΔoxyR (repaired) (lane 5) using polyclonal rat OxyR antiserum as the primary antibody. The black arrow on the right indicates the position of the OxyR protein. (B) Comparison of the growth rates of M. catarrhalis O35E (▪), O35EΔoxyR (•), O35EΔoxyR(pWL01) (□), O35EΔoxyR(pWW115) (○), and O35EΔoxyR (repaired) (▾). Results of a representative experiment are shown. (C) Sensitivities of the five strains for which results are shown in panels A and B to 88 mM H2O2 in disk diffusion assays. (D) Diameter of the zone of growth inhibition for each strain for which results are shown in panel C. Statistical analysis utilizing two-way ANOVA was utilized to determine the significance of each strain's zone of growth inhibition relative to that of wild-type M. catarrhalis O35E. Significant differences from the diameter of the zone of growth inhibition of M. catarrhalis O35E (bar 1) were observed for the zones of growth inhibition obtained with M. catarrhalis O35EΔoxyR (bar 2) and O35EΔoxyR(pWW115) (bar 4).

Sensitivities of M. catarrhalis oxyR mutant constructs to H2O2.

The M. catarrhalis O35E oxyR mutant (Fig. 3C2) was more sensitive to killing by H2O2 than was the wild-type parent strain (Fig. 3C1), as determined by the disk diffusion method. Similarly, the oxyR mutant containing the empty plasmid vector (Fig. 3C4) was also more sensitive to killing by H2O2. These differences were significant as determined by two-way ANOVA (Fig. 3D) (P, ≤0.05). The zones of growth inhibition caused by H2O2 with the complemented oxyR mutant (Fig. 3C3) and the repaired mutant (Fig. 3C5) were very similar to that obtained with the wild-type parent strain; the differences were not significant.

Aerobic serial dilution defect of the M. catarrhalis O35EΔoxyR mutant.

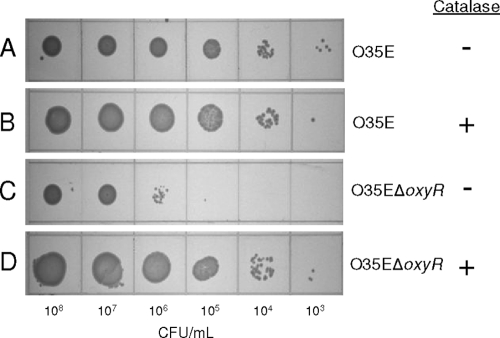

When spotted onto BHI agar, the M. catarrhalis O35EΔoxyR mutant was unable to form single colonies below a density of 106 CFU/ml (Fig. 4 C). In contrast, the wild-type M. catarrhalis strain O35E was capable of single-colony formation at a cellular density approximately 1,000-fold less (Fig. 4A). This serial dilution defect seen with the oxyR mutant was eliminated by the addition of exogenous catalase to the medium at the time of plating, such that oxyR mutant cells demonstrated the ability to form single colonies at a cellular density of 103 CFU/ml (Fig. 4D). The provision of catalase to wild-type cells (Fig. 4B) did not increase their ability to form individual colonies beyond that observed in the absence of exogenously supplied catalase (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Catalase reverses the aerobic serial dilution defect of the M. catarrhalis O35EΔoxyR mutant. Serial dilutions of the wild-type strain O35E (A and B) and the O35EΔoxyR mutant (C and D) were spotted onto BHI agar either lacking catalase (−) or containing catalase (+) and were then incubated overnight.

Transcriptional response of the M. catarrhalis O35E katA, ahpC, and ahpF genes to increasing concentrations of exogenous H2O2 as measured by real-time RT-PCR.

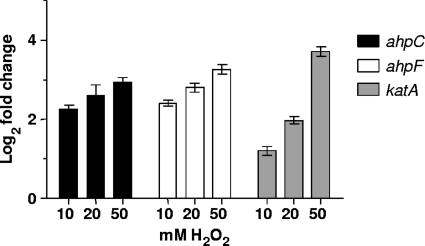

Inspection of the annotation of the M. catarrhalis ATCC 43617 genome (60) identified a gene (Fig. 1B) encoding a predicted protein that was 83% identical (E value, 0.0) to the KatA catalase (GenBank accession number YP_208798.1) of N. gonorrhoeae. Because bacterial catalases (e.g., KatA) and peroxidases (e.g., AhpCF) are involved in the ability to resist killing by H2O2, it was of interest to determine whether the expression of these genes in M. catarrhalis would be affected by exposure of the bacterium to exogenous H2O2. Wild-type M. catarrhalis O35E cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of H2O2, and the transcriptional responses of these three genes were measured by real-time RT-PCR. All three of the genes tested demonstrated a dose-dependent transcriptional response to the increasing concentrations of H2O2, with katA exhibiting the greatest response (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Transcriptional responses of the M. catarrhalis O35E ahpC, ahpF, and katA genes to increasing concentrations of exogenous H2O2 as measured by real-time RT-PCR. Cultures of wild-type M. catarrhalis O35E growing in BHI broth were exposed to increasing concentrations of H2O2 (10, 20, and 50 mM), and total RNA was extracted and utilized in real-time RT-PCRs with primer pairs specific for the M. catarrhalis ahpC (filled bars), ahpF (open bars), or katA (shaded bars) gene. These data are reported as the fold change in transcription from that of M. catarrhalis cells that were exposed to water instead of H2O2.

Oxidative stress response of M. catarrhalis O35E as measured by DNA microarray analysis.

DNA microarray analysis was utilized to measure the relative changes in the transcriptome of strain O35E after exposure to 50 mM H2O2. The 30 genes most up- or downregulated in response to H2O2 exposure are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Real-time RT-PCR was utilized to measure the expression patterns of a selected group of genes that DNA microarray analysis indicated were affected by exposure to H2O2 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). There was good correlation between the values obtained by DNA microarray analysis and those derived from real-time RT-PCR (R2, 0.93).

The genes most upregulated by H2O2 in these wild-type cells included those encoding a hypothetical protein (MC701), isocitrate lyase, and malate synthase, the KatA catalase, the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase CF, and aconitate hydratase (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Among those genes most downregulated by H2O2 were two encoding proteins involved in phosphate uptake, three encoding hypothetical proteins, and one encoding bacterioferritin (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

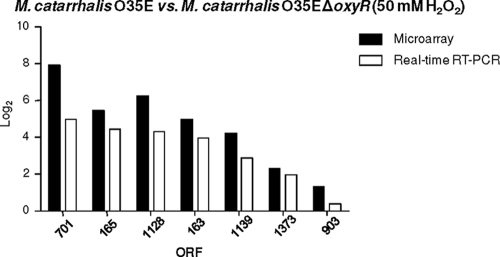

In an additional set of DNA microarray experiments, both the wild-type strain O35E and the O35EΔoxyR mutant were exposed to H2O2 in order to identify genes whose regulation was dependent on the presence of a functional OxyR protein. Expression of OxyR was found to be essential for the pronounced upregulation of genes (MC701 and MC1128) encoding two hypothetical proteins, as well as for that of the genes encoding ahpC, ahpF, and katA (Table 3). Real-time RT-PCR analysis of selected genes (Fig. 6) identified in this second set of DNA microarray experiments again showed good correlation between the two sets of data (R2, 0.92). Interestingly, no genes were found to be downregulated by OxyR under these oxidative stress conditions.

TABLE 3.

OxyR-dependent M. catarrhalis gene expression under conditions of oxidative stressa

| ORF | Description | Median log2 ratio of expression with/without oxyRb | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| MC701 | Hypothetical protein | 7.89 | 0.82 |

| MC1128 | Protein of unknown function | 6.25 | 0.07 |

| MC165 | Probable alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit F | 5.46 | 0.43 |

| MC163 | Putative alkyl hydroperoxide reductase, subunit C | 4.97 | 0.14 |

| MC1139 | KatA | 4.22 | 0.17 |

| MC702 | Adenosylmethionine-8-amino-7-oxononanoate aminotransferase | 3.01 | 0.12 |

| MC286 | Probable UDP-3-O-acyl N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase | 2.55 | 0.21 |

| MC1373 | Ferric uptake regulation protein | 2.33 | 0.13 |

| MC1390 | GTP diphosphokinase | 2.22 | 0.07 |

| MC351 | OsmC-like protein | 1.98 | 0.12 |

| MC1362 | Ferrochelatase | 1.54 | 0.18 |

| MC734 | Probable glutamyl-tRNA reductase | 1.48 | 0.09 |

| MC903 | Transcriptional regulator, BadM/Rrf2 family | 1.29 | 0.09 |

| MC1922 | Glutamate synthase (NADPH) | 1.26 | 0.10 |

| MC907 | Cochaperone Hsc20 | 1.26 | 0.09 |

| MC906 | Iron-sulfur cluster assembly protein IscA | 1.23 | 0.08 |

| MC905 | FeS cluster assembly scaffold IscU | 1.15 | 0.05 |

| MC904 | Cysteine desulfurase IscS | 1.15 | 0.10 |

This table includes all of the ORFs with altered expression after exposure to 50 mM H2O2.

Median log2 ratio of expression in M. catarrhalis O35E to expression in M. catarrhalis O35EΔoxyR when both strains were exposed to 50 mM H2O2. The data represent three independent experiments (P < 0.05).

FIG. 6.

Comparison of selected DNA microarray data with real-time RT-PCR results for gene expression as affected by the presence of H2O2 and OxyR. Shown are the effects of the presence of 50 mM H2O2 on the expression of selected genes by strain O35E in the presence and absence of the oxyR gene product, as measured by DNA microarray analysis (filled bars) and real-time RT-PCR (open bars).

Construction and characterization of mutations in ORFs MC701 and MC1128.

The very marked increase in the expression of MC701 and MC1128 under conditions of oxidative stress (Table 3) prompted the construction of O35E deletion mutants unable to express the proteins encoded by these two genes. However, when tested in the disk diffusion assay for their sensitivity to killing by H2O2, these two mutants exhibited levels of resistance equivalent to that of the wild-type O35E strain (data not shown).

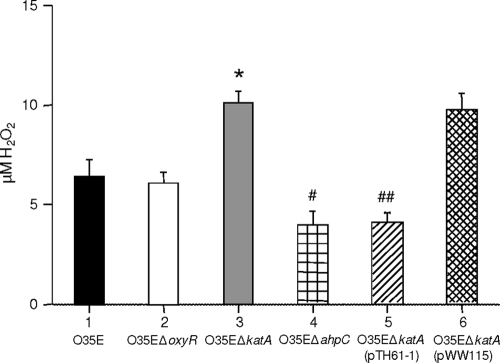

H2O2 decomposition by wild-type, mutant, and recombinant strains of M. catarrhalis.

Incubation of cell suspensions of wild-type M. catarrhalis O35E (Fig. 7, bar 1) and the O35EΔoxyR mutant (Fig. 7, bar 2) with 10 μM H2O2 resulted in degradation of H2O2 to levels that did not differ between these two strains. In contrast, the O35EΔkatA mutant (Fig. 7, bar 3) scavenged little or no H2O2 in the same time period. Provision of a wild-type katA gene in trans allowed the recombinant strain O35EΔkatA(pTH61-1) (Fig. 7, bar 5) to degrade H2O2 more rapidly (P, 0.05) than its wild-type parent strain (Fig. 7, bar 1). The presence of the pWW115 cloning vector in the O35EΔkatA mutant (Fig. 7, bar 6) did not significantly alter the ability of this mutant to scavenge H2O2. The O35EΔahpC mutant (Fig. 7, bar 4) exhibited an ability to scavenge H2O2 that was greater (P, 0.002) than that of the wild-type parent strain (Fig. 7, bar 1) and equivalent to that of the recombinant strain O35EΔkatA(pTH61-1) (Fig. 7, bar 5).

FIG. 7.

Abilities of different M. catarrhalis strains and constructs to scavenge H2O2. H2O2 was added to a final concentration of 10 μM to ∼1.6 × 107 CFU of bacteria and was incubated for 1 min at room temperature. A nonsignificant difference in the scavenging of H2O2 was seen between M. catarrhalis O35EΔoxyR (bar 2) and the wild-type strain O35E (bar 1). A statistically significant reduction in the scavenging of H2O2 was observed for O35EΔkatA (*, P = 0.01) (bar 3). Significant increases in the scavenging of H2O2 by O35EΔahpC (#, P = 0.002) (bar 4) and O35EΔkatA(pTH61-1) (bar 5) (##, P = 0.05) over that by the wild-type strain O35E were observed. O35EΔkatA(pWW115) (bar 6) degraded H2O2 to about the same extent as the ΔkatA mutant.

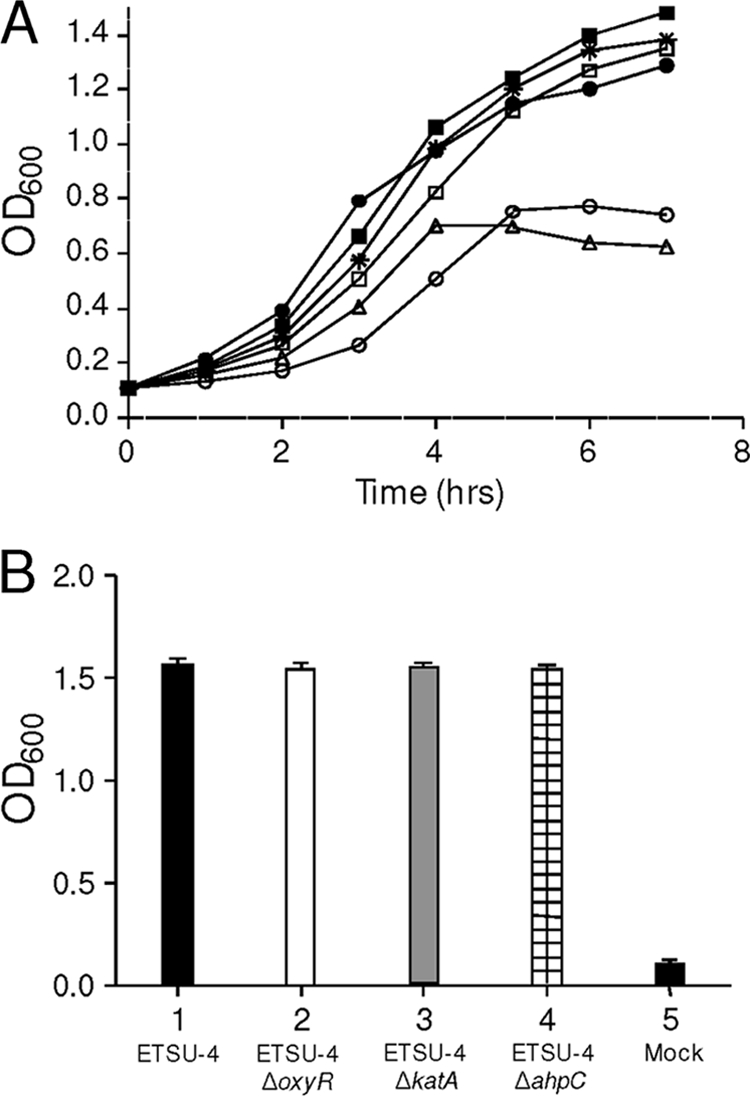

Effects of the oxyR, ahpC, and katA mutations on the growth response to exogenous H2O2 and on biofilm formation.

M. catarrhalis O35E forms very poor biofilms in a crystal violet-based biofilm assay system (36). To determine whether any of the mutations described above had an effect on biofilm development, ΔoxyR, ΔahpC, and ΔkatA mutants were constructed in M. catarrhalis ETSU-4, which exhibits robust biofilm development in this assay system. The effect of the addition of 50 mM H2O2 (final concentration) to cells of these strains growing in broth was examined first, and it was found that only the growth of the ETSU-4ΔkatA mutant (Fig. 8A) was markedly inhibited by this concentration of H2O2. After an additional 3.5 h of growth, a portion of this ETSU-4ΔkatA broth culture was plated on BHI agar; no viable cells were present (data not shown). Both the wild-type ETSU-4 strain and the ETSU-4ΔahpC mutant exhibited little or no change in the growth rate after the addition of H2O2, while the ETSU-4ΔoxyR mutant showed only a modest decrease in its rate of growth (Fig. 8A). Provision of a wild-type O35E katA gene (in pTH61-1) in trans in the ETSU-4ΔkatA mutant resulted in a wild-type-like response to H2O2, whereas the presence of the plasmid vector pWW115 in the same mutant did not change its response to H2O2 (Fig. 8A). When the ETSU-4 wild-type strain and its oxyR, katA, and ahpC mutants were used in the crystal violet-based biofilm system, there was no apparent difference between the wild-type strain and any of these three mutants (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

Effects of oxyR, ahpC, and katA mutations on the growth response to exogenous H2O2 and on biofilm formation. (A) Growth response of wild-type M. catarrhalis ETSU-4 (•), the ETSU-4ΔoxyR mutant (□), the ETSU-4ΔahpC mutant (*), the ETSU-4ΔkatA mutant (▵), ETSU-4ΔkatA(pTH61-1) (▪), and ETSU-4ΔkatA(pWW115) (○) after the addition of H2O2 to a final concentration of 50 mM. H2O2 was added to each culture when it reached an OD600 of 0.7. No viable M. catarrhalis ETSU-4ΔkatA cells were isolated from the culture at the end of the experiment. (B) Measurement of biofilm formation by wild-type M. catarrhalis ETSU-4 (bar 1), M. catarrhalis ETSU-4ΔoxyR (bar 2), M. catarrhalis ETSU-4ΔkatA (bar 3), and M. catarrhalis ETSU-4ΔahpC (bar 4) in the crystal violet-based biofilm assay. Bar 5 shows the result obtained from a mock (uninoculated) well.

DISCUSSION

Evaluation of the sensitivity of M. catarrhalis O35E to oxidative stress revealed remarkable resistance to killing by exogenous H2O2, a result reinforcing that reported by Weiser and colleagues (38), who indicated that an isolate of M. catarrhalis (strain Bc1) was more resistant to killing by H2O2 than either S. pneumoniae or H. influenzae. The levels of resistance to killing by H2O2 were very similar among the four M. catarrhalis wild-type strains tested in the present study, indicating that M. catarrhalis possesses a well-conserved and robust set of factors for dealing with oxidative stress. This relatively high innate level of resistance to exogenous oxidative stress may be a reflection of the environmental niche in which M. catarrhalis typically resides, specifically the nasopharyngeal mucosa and, during times of exacerbation, the lungs of adult patients with COPD. A recent study of patients with COPD demonstrated that at baseline, these patients exhaled a larger amount of H2O2 than healthy controls, and the level of exhaled H2O2 rose significantly at the time of an exacerbation (3). It should also be noted that freshly prepared BHI liquid medium was utilized for all of the experiments in the present study. Bacteriological media can undergo oxidation during storage, resulting in the endogenous production of 1 to 20 μM H2O2 (10, 15). This finding raises the possibility that H2O2 in the culture medium could induce the bacterial oxidative stress response prior to the addition of exogenous H2O2. This, in turn, could result in an artificially increased level of resistance to killing by H2O2.

This high level of H2O2 resistance among different M. catarrhalis strains led to genome-wide screening for gene products relevant to oxidative stress. BLAST analysis of the M. catarrhalis ATCC 43617 (60) genome first identified an ORF encoding a protein with similarity to OxyR, a LysR family transcriptional regulator first studied in E. coli (7, 51). In both this enteric organism and other Gram-negative bacterial pathogens, OxyR has been shown to be an important regulator of the bacterial response to oxidative stress (9, 11, 14, 24). OxyR is a redox-sensitive transcriptional regulator in E. coli that has two functional domains (28, 33). The N-terminal domain contains a helix-turn-helix motif that is responsible for binding DNA (21). The C-terminal domain (i.e., the “regulatory domain”) resembles periplasmic binding components of ABC transporters. In this part, there are two cysteine residues that are critical for the function of the protein. The sulfhydryl group of one of the cysteines (C199 in E. coli OxyR) is susceptible to oxidation under oxidative stress (61). Oxidation of this moiety precipitates the formation of a disulfide bridge between the oxidized residue and the side chain of the second cysteine (C208 in E. coli OxyR). This conformational rearrangement is presumably the structural signal that changes the DNA-binding characteristics of the protein (5, 61). The two cysteines (C200 and C209 in M. catarrhalis OxyR) are conserved between these two proteins.

Additional analysis of the oxyR locus in M. catarrhalis O35E revealed two genes with homology to ahpF and ahpC, in close proximity to oxyR (Fig. 1). In some other bacteria, these two genes encode proteins that constitute an alkyl hydroperoxide reductase system (39) shown to be important for the handling of oxidative stress (34, 43, 53). Finally, a gene (katA) encoding a catalase homolog was identified via genome screening, providing additional evidence that M. catarrhalis has the potential to mount an effective response to oxidative stress. The genome of M. catarrhalis strain RH4 was reported not to contain an oxyR homolog (8), but our BLAST analysis indicated that RH4 contains an ORF encoding a protein that is 99.6% identical to the O35E OxyR protein. The studies described here demonstrate that there is an OxyR protein encoded by all of the strains of M. catarrhalis utilized in this study and that it is involved in the regulation of a coordinated gene response to combat oxidative stress.

The growth defect seen with the M. catarrhalis oxyR mutant (Fig. 3B) indicates that OxyR is also important for the bacterial response to physiologic levels of H2O2 that are generated by the bacterium during normal aerobic growth. Rapid cellular metabolism occurs during logarithmic bacterial growth, and it is possible that significant amounts of endogenous oxidative stressors are generated, although the predominant source of these remains to be determined (44). It is likely that the growth of the oxyR mutant in broth (Fig. 3B) is diminished due to its decreased ability to deal with this endogenously generated oxidative stress. While it is likely that this growth defect is caused by the altered ability of the oxyR mutant to degrade H2O2, the studies reported here do not exclude the possibility that the lack of OxyR could have other deleterious effects on the growth of M. catarrhalis. Additionally, the increased susceptibility of the oxyR mutant to exogenously provided H2O2 in the disk diffusion studies (Fig. 3C) shows that the expression of oxyR is important for the bacterial response to exogenous H2O2.

The M. catarrhalis oxyR mutant was also unable to form individual, isolated colonies on agar medium when plated at a density less than 1 × 106 CFU/ml (Fig. 4). A similar phenotype has been reported for oxyR mutants of both P. aeruginosa (10) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (11). The addition of exogenous catalase to the medium allowed the M. catarrhalis oxyR mutant to form single colonies at levels equivalent to those obtained with the wild-type parent strain. While several theories have been proposed for this cellular density threshold effect (10, 11), the ability of exogenous catalase to abrogate this particular mutant phenotype indicates that the ability to increase expression of the KatA catalase (or other antioxidant factors) is necessary for individual colony formation by M. catarrhalis below a certain cell density. As suggested by Hassett et al. (10), catalase could be released from lysed bacteria and could then protect other bacterial cells from H2O2 in the growth environment.

Increasing levels of exogenous H2O2 resulted in an apparent dose-dependent increase in the transcription of three M. catarrhalis genes predicted to encode proteins involved in the decomposition of H2O2: katA, ahpC, and ahpF. The ability to modulate the expression of genes encoding products involved in resistance to oxidative stress is likely the result of a need for M. catarrhalis to respond to rapidly changing environmental conditions, including the influx of immune cells, increases in the numbers of competing bacteria that can produce H2O2, and elevated levels of exhaled oxidants in the lungs of COPD patients. While the genes described above are known to be important for the bacterial response to oxidative stress in other bacterial systems, it was reasonable to assume that M. catarrhalis encoded additional genes that are involved with the coordinated effort to resolve oxidative stress. Therefore, DNA microarray technology was utilized to evaluate the transcriptome of M. catarrhalis in response to exogenous H2O2. The use of H2O2 as a source of exogenous oxidative stress has been utilized previously to study the transcriptomes of E. coli (62), N. gonorrhoeae (45), and H. influenzae (9).

DNA microarray analysis indicated that several types of genes were upregulated by wild-type M. catarrhalis in the presence of oxidative stress. Two primary groups of genes were identified as being highly upregulated in the presence of a functional OxyR protein: (i) those encoding products involved with the direct breakdown of oxidative stress factors (e.g., ahpCF, katA, and MC2, encoding a probable organic hydroperoxide resistance protein) and (ii) those encoding products important for the regulation and uptake of iron and the subsequent bacterial management of iron stores (e.g., MC905 and MC906, encoding proteins involved in iron-sulfur cluster assembly; MC1362, encoding a ferrochelatase; and MC1373, encoding Fur). The upregulation of genes involved with oxidative stress metabolism and iron-sulfur handling has been seen previously in the oxidative stress responses of other bacteria, including H. influenzae (9), N. gonorrhoeae (45), and E. coli (62). In general, the degree of downregulation of genes by addition of H2O2 was not as pronounced as that seen with upregulated genes in the wild-type strain (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Interestingly, the M. catarrhalis ORFs encoding isocitrate lyase and malate synthase were among the genes most upregulated by oxidative stress (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). These two enzymes constitute the glyoxylate bypass of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (20), which functions in an anaplerotic manner. A recent study of the ability of Pseudomonas fluorescens to resist oxidative stress indicated that these two enzymes formed part of a metabolic network that produces NADPH at the expense of NADH, a prooxidant (47). Whether the increased transcription of these two genes in M. catarrhalis cells undergoing oxidative stress indicates similar roles for these enzymes in M. catarrhalis is not known. Additionally, two other unlinked genes (MC701 and MC1128) encoding hypothetical proteins were very highly upregulated, but inactivation of these two genes did not detectably affect the ability of M. catarrhalis to resist killing by exogenous H2O2 (data not shown).

The studies described above provide the first description of gene products involved in the robust ability of M. catarrhalis to deal with oxidative stress. Why M. catarrhalis is so much more resistant to killing by H2O2 than other pathogens that colonize the nasopharynx is not apparent but could involve either more catalytically active antioxidant enzymes or a much higher level of expression of one or more antioxidant enzymes. The clinical relevance of this finding is likely based on the need for this bacterium to colonize and survive in several hostile in vivo environments, including the nasopharynx and the respiratory tracts of adult patients with COPD. Further studies will be necessary to elucidate the extent of the OxyR regulon and to determine the molecular basis for the impressive ability of M. catarrhalis to resist killing by H2O2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants AI076365 to T.C.H. and AI36344 to E.J.H. S.N.J. was supported by U.S. Public Health Service training grant 5-T32-AI007520.

Editor: S. M. Payne

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 November 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attia, A. S., S. Ram, P. A. Rice, and E. J. Hansen. 2006. Binding of vitronectin by the Moraxella catarrhalis UspA2 protein interferes with late stages of the complement cascade. Infect. Immun. 74:1597-1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borrill, Z. L., K. Roy, and D. Singh. 2008. Exhaled breath condensate biomarkers in COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 32:472-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budhani, R. K., and J. K. Struthers. 1998. Interaction of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis: investigation of the indirect pathogenic role of beta-lactamase-producing moraxellae by use of a continuous-culture biofilm system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2521-2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi, H., et al. 2001. Structural basis of the redox switch in the OxyR transcription factor. Cell 105:103-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christman, M. F., R. W. Morgan, F. S. Jacobson, and B. N. Ames. 1985. Positive control of a regulon for defenses against oxidative stress and some heat-shock proteins in Salmonella typhimurium. Cell 41:753-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christman, M. F., G. Storz, and B. N. Ames. 1989. OxyR, a positive regulator of hydrogen peroxide-inducible genes in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, is homologous to a family of bacterial regulatory proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:3484-3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Vries, S. P., et al. 2010. Genome analysis of Moraxella catarrhalis strain RH4, a human respiratory tract pathogen. J. Bacteriol. 192:3574-3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison, A., et al. 2007. The OxyR regulon in nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 189:1004-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassett, D. J., et al. 2000. A protease-resistant catalase, KatA, released upon cell lysis during stationary phase is essential for aerobic survival of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa oxyR mutant at low cell densities. J. Bacteriol. 182:4557-4563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hennequin, C., and C. Forestier. 2009. oxyR, a LysR-type regulator involved in Klebsiella pneumoniae mucosal and abiotic colonization. Infect. Immun. 77:5449-5457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hishinuma, S., M. Yuki, M. Fujimura, and F. Fukumori. 2006. OxyR regulated the expression of two major catalases, KatA and KatB, along with peroxiredoxin, AhpC in Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. 8:2115-2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horton, R. M., Z. Cai, S. N. Ho, and L. R. Pease. 1990. Gene splicing by overlap extension: tailor-made genes using the polymerase chain reaction. Biotechniques 8:528-535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ieva, R., et al. 2008. OxyR tightly regulates catalase expression in Neisseria meningitidis through both repression and activation mechanisms. Mol. Microbiol. 70:1152-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imlay, J. A. 2008. Cellular defenses against superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77:755-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones, D. T. 1999. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 292:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabsch, W., and C. Sander. 1983. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22:2577-2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karalus, R., and A. Campagnari. 2000. Moraxella catarrhalis: a review of an important human mucosal pathogen. Microbes Infect. 2:547-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiss, K., W. Liu, J. F. Huntley, M. V. Norgard, and E. J. Hansen. 2008. Characterization of fig operon mutants of Francisella novicida U112. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 285:270-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kornberg, H. L., and H. A. Krebs. 1957. Synthesis of cell constituents from C2-units by a modified tricarboxylic acid cycle. Nature 179:988-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kullik, I., J. Stevens, M. B. Tolendano, and G. Storz. 1995. Mutational analysis of the redox-sensitive transcriptional regulator OxyR: regions important for DNA binding and multimerization. J. Bacteriol. 177:1285-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labandeira-Rey, M., J. R. Mock, and E. J. Hansen. 2009. Regulation of expression of the Haemophilus ducreyi LspB and LspA2 proteins by CpxR. Infect. Immun. 77:3402-3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larkin, M. A., et al. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947-2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau, G. W., B. E. Britigan, and D. J. Hassett. 2005. Pseudomonas aeruginosa OxyR is required for full virulence in rodent and insect models of infection and for resistance to human neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 73:2550-2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, H. Y., et al. 2004. Antimicrobial activity of innate immune molecules against Streptococcus pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. BMC Infect. Dis. 4:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luke, N. R., and A. A. Campagnari. 1999. Construction and characterization of Moraxella catarrhalis mutants defective in expression of transferrin receptors. Infect. Immun. 67:5815-5819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maciver, I., and E. J. Hansen. 1996. Lack of expression of the global regulator OxyR in Haemophilus influenzae has a profound effect on growth phenotype. Infect. Immun. 64:4618-4629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maddocks, S. E., and P. C. Oyston. 2008. Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology 154:3609-3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLean, S., L. A. Bowman, G. Sanguinetti, R. C. Read, and R. K. Poole. 2010. Peroxynitrite toxicity in Escherichia coli K12 elicits expression of oxidative stress responses and protein nitration and nitrosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 285:20724-20731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morgan, R. W., M. F. Christman, F. S. Jacobson, G. Storz, and B. N. Ames. 1986. Hydrogen peroxide-inducible proteins in Salmonella typhimurium overlap with heat shock and other stress proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83:8059-8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy, T. F., and G. I. Parameswaran. 2009. Moraxella catarrhalis, a human respiratory tract pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:124-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nochi, T., and H. Kiyono. 2006. Innate immunity in the mucosal immune system. Curr. Pharm. Des. 12:4203-4213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paget, M. S., and M. J. Buttner. 2003. Thiol-based regulatory switches. Annu. Rev. Genet. 37:91-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panmanee, W., and D. J. Hassett. 2009. Differential roles of OxyR-controlled antioxidant enzymes alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpCF) and catalase (KatB) in the protection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa against hydrogen peroxide in biofilm vs. planktonic culture. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 295:238-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pearson, M. M., and E. J. Hansen. 2007. Identification of gene products involved in biofilm production by Moraxella catarrhalis ETSU-9 in vitro. Infect. Immun. 75:4316-4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pearson, M. M., C. A. Laurence, S. E. Guinn, and E. J. Hansen. 2006. Biofilm formation by Moraxella catarrhalis in vitro: roles of the UspA1 adhesin and the Hag hemagglutinin. Infect. Immun. 74:1588-1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pei, J., B. H. Kim, and N. V. Grishin. 2008. PROMALS3D: a tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:2295-2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pericone, C. D., K. Overweg, P. W. Hermans, and J. N. Weiser. 2000. Inhibitory and bactericidal effects of hydrogen peroxide production by Streptococcus pneumoniae on other inhabitants of the upper respiratory tract. Infect. Immun. 68:3990-3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poole, L. B. 2005. Bacterial defenses against oxidants: mechanistic features of cysteine-based peroxidases and their flavoprotein reductases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 433:240-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rada, B., and T. L. Leto. 2008. Oxidative innate immune defenses by Nox/Duox family NADPH oxidases. Contrib. Microbiol. 15:164-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robinson, J. M. 2008. Reactive oxygen species in phagocytic leukocytes. Histochem. Cell Biol. 130:281-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 43.Seaver, L. C., and J. A. Imlay. 2001. Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase is the primary scavenger of endogenous hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:7173-7181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seaver, L. C., and J. A. Imlay. 2004. Are respiratory enzymes the primary sources of intracellular hydrogen peroxide? J. Biol. Chem. 279:48742-48750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seib, K. L., et al. 2007. Characterization of the OxyR regulon of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Microbiol. 63:54-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sethi, S., N. Evans, B. J. Grant, and T. F. Murphy. 2002. New strains of bacteria and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:465-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh, R., J. Lemire, R. J. Mailloux, and V. D. Appanna. 2008. A novel strategy involved in [corrected] anti-oxidative defense: the conversion of NADH into NADPH by a metabolic network. PLoS One 3:e2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Söding, J. 2005. Protein homology detection by HMM-HMM comparison. Bioinformatics 21:951-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Söding, J., A. Biegert, and A. N. Lupas. 2005. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:W244-W248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Storz, G., and M. Zheng. 2000. Oxidative stress, p. 47-59. In G. Storz and R. Hengge-Aronis (ed.), Bacterial stress responses. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 51.Storz, G., and S. Altuvia. 1994. OxyR regulon. Methods Enzymol. 234:217-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Storz, G., and J. A. Imlay. 1999. Oxidative stress. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:188-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Storz, G., et al. 1989. An alkyl hydroperoxide reductase induced by oxidative stress in Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli: genetic characterization and cloning of ahp. J. Bacteriol. 171:2049-2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tano, K., et al. 2003. Is hydrogen peroxide responsible for the inhibitory activity of alpha-haemolytic streptococci sampled from the nasopharynx? Acta Otolaryngol. 123:724-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tano, K., E. G. Hakansson, S. E. Holm, and S. Hellstrom. 2002. Bacterial interference between pathogens in otitis media and alpha-haemolytic streptococci analysed in an in vitro model. Acta Otolaryngol. 122:78-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tseng, H. J., A. G. McEwan, M. A. Apicella, and M. P. Jennings. 2003. OxyR acts as a repressor of catalase expression in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect. Immun. 71:550-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Unhanand, M., et al. 1992. Pulmonary clearance of Moraxella catarrhalis in an animal model. J. Infect. Dis. 165:644-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.VanBogelen, R. A., P. M. Kelley, and F. C. Neidhardt. 1987. Differential induction of heat shock, SOS, and oxidation stress regulons and accumulation of nucleotides in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169:26-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang, W., and E. J. Hansen. 2006. Plasmid pWW115, a cloning vector for use with Moraxella catarrhalis. Plasmid 56:133-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang, W., et al. 2007. Metabolic analysis of Moraxella catarrhalis and the effect of selected in vitro growth conditions on global gene expression. Infect. Immun. 75:4959-4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zheng, M., F. Aslund, and G. Storz. 1998. Activation of the OxyR transcription factor by reversible disulfide bond formation. Science 279:1718-1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng, M., et al. 2001. DNA microarray-mediated transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli response to hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 183:4562-4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.