Abstract

The virulence of the dental caries pathogen Streptococcus mutans relies in part on the sucrose-dependent synthesis of and interaction with glucan, a major component of the extracellular matrix of tooth biofilms. However, the mechanisms by which secreted and/or cell-associated glucan-binding proteins (Gbps) produced by S. mutans participate in biofilm growth remain to be elucidated. In this study, we further investigate GbpB, an essential immunodominant protein with similarity to murein hydrolases. A conditional knockdown mutant that expressed gbpB antisense RNA under the control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter was constructed in strain UA159 (UACA2) and used to investigate the effects of GbpB depletion on biofilm formation and cell surface-associated characteristics. Additionally, regulation of gbpB by the two-component system VicRK was investigated, and phenotypic analysis of a vicK mutant (UAvicK) was performed. GbpB was directly regulated by VicR, and several phenotypic changes were comparable between UACA2 and UAvicK, although differences between these strains existed. It was established that GbpB depletion impaired initial phases of sucrose-dependent biofilm formation, while exogenous native GbpB partially restored the biofilm phenotype. Several cellular traits were significantly affected by GbpB depletion, including altered cell shape, decreased autolysis, increased cell hydrophobicity, and sensitivity to antibiotics and osmotic and oxidative stresses. These data provide the first experimental evidence for GbpB participation in sucrose-dependent biofilm formation and in cell surface properties.

The virulence of Streptococcus mutans, the major pathogen of dental caries, depends in part on the expression of surface proteins involved in the synthesis of and interaction with an extracellular glucan matrix. This process might influence several factors that modulate biofilm ecology, such as population density, nutrient availability, diffusion of metabolites, and evasion of host immune components. Among these proteins, glucosyltransferases (GtfB, GtfC, and GtfD) synthesize glucan from sucrose. Additionally, it has been suggested that other surface proteins with affinity for glucan, i.e., glucan-binding proteins (Gbps), contribute to S. mutans biofilm growth, and hence virulence, by mediating bacterial interaction with extracellular glucan (reviewed in reference 4). S. mutans expresses at least four Gbps (GbpA, GbpB, GbpC, and GbpD), but apart from their affinity for glucan, these proteins differ in structure, function, and immunological properties (4, 24).

GbpB has unique immunodominant properties in children and adults (45, 46) and induces protective antibody responses to experimental caries in animal models (48). In addition, strong natural salivary IgA responses to GbpB during the initial phases of S. mutans challenge were associated with low susceptibility to S. mutans colonization in young children (34, 35). For a large number of strains with different biofilm phenotypes, production of GbpB was associated positively with the amounts of biofilms formed in vitro (28, 29). Formally, GbpB expression appeared essential for viability in several S. mutans strains, since bona fide gbpB mutants could not be isolated (30), except for a mutant with limited viability recovered for strain GS5 (12), a strain with several mutations in its genome (18, 41).

GbpB orthologues have been found in several Gram-positive species (28), including proteins, designated PcsB (protein required for cell separation of GBS), expressed by Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococci [GBS]) (38) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (32). PcsB/GbpB proteins differ in a central variable domain (120 amino acid residues), and there is evidence that PcsB/GbpB-like proteins have species-specific functions (31). For GBS, pcsB could be deleted in one strain under conditions of osmotic protection (38), while for S. pneumoniae strains R6 and D29, it was not possible to isolate pcsB null mutants (5, 31). Downregulation of pcsB in S. pneumoniae strain R6 provided evidence that PcsB functions in cell wall growth and septum division (31). For S. mutans GS5, the gbpB null mutant exhibited aberrant cell shape and slow growth (12), but because of its limited viability, further investigation of the role of GbpB in biofilm growth could not be performed. However, there is no experimental evidence that GbpB functions directly in cell wall biogenesis or division. Therefore, in the present study, we used an antisense RNA strategy to downregulate gbpB to explore protein function in S. mutans. We analyzed the effects of gbpB downregulation on the biofilm phenotype and on several traits associated with a role in cell surface properties. Because of evidence suggesting that gbpB is regulated by the two-component system (TCS) VicRK (43), we also investigated whether gbpB is directly regulated by this system and compared the phenotypes of gbpB knockdown and vicK mutant strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, growth conditions, and reagents.

Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study are shown in Table 1. All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless specified otherwise. A vicK mutant strain of UA159 (UAvicK) was obtained by double-crossover recombination with a null allele constructed by PCR-ligation (22), using the primers listed in Table 1, such that vicK was replaced by an erythromycin resistance gene. Streptococcus gordonii strain Challis and Escherichia coli DH5α were used for plasmid propagation. Streptococcal strains were cultivated in brain heart infusion broth (BHI; Difco) or tryptic soy agar (TSA) at 37°C and 10% CO2. Erythromycin (5 μg/ml) was added to media for selection and maintenance of conditional mutant or plasmid-containing strains. The Tet promoter was induced by doxycycline (dox) at 50, 100, 150, and 200 ng/ml. Purified native GbpB (pGbpB) was obtained by high-pressure liquid chromatography from S. mutans culture fluids as described elsewhere (45). Purified protein was stored in aliquots at −70°C in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8).

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or oligonucleotide | Relevant characteristics or sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Reference, source, 5′ position, product size, or restriction site |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. mutans strains | ||

| UA159 | Erms | ATCC |

| UACA2 | UA159/ptetASgbpB; Ermr | This study |

| UA223 | UA159/pMM223; Ermr | This study |

| UAvicK | UA159 ΔvicK::Ermr | This study |

| S. gordonii strains | ||

| Challis | Erms | H. K. Kuramitsu |

| Challis CA2 | Propagation of ptetASgbpB; ermr | This study |

| E. coli strain | ||

| DH5α | General cloning and plasmid propagation | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pVA838 | Ermr cassette source | 26 |

| pMM223 | 8 kb; Ermr; ori of E. coli, Streptococcus | H. K. Kuramitsu (52) |

| pALC2073 | 6.41 kb, with TetO/TetR sequence | Ambrose L. Cheung (6) |

| ptetASGbpB | 8.8 kb; Ermr; pMM223 with a 220-bp sequence of gbpB (positions 19 to 260) in the antisense orientation under the control of the TetO/TetR promoter | This study |

| Primers | ||

| Ptet-5 | GGAATTCAAGCTTGCATCCCTGCAG | EcoRI (53) |

| Ptet-6 | GAAGATCTATTCGAGCTCGGTACCC | BglII (53) |

| TetF | TGT TTT TCT GTA GGC CGT GT | Position 19 of TetO/TetR promoter |

| ASGbpBF | TCAGCAGTTTTAGTGAGTGGTG | Position 18 of gbpB |

| ASGbpBR | TTGGTACCCCCAAAGTAGCAGACTGAGCTT | Position 259 of gbpB; KpnI |

| CGbpBF | CAACAGAAGCACAACCATCA | Position 920 of gbpB |

| CGbpBR | TGTCCACCATTACCCCAGT | Position 1070 of gbpB |

| 16SRNA-F | CGGCAAGCTAATCTCTGAAA | |

| 16SRNA-R | GCCCCTAAAAGGTTACCTCA | 49 |

| E1-AscI | TTGGCGCGCCTGGCGGAAACGTAAAAGAAG | Ermr cassette from pVA838 |

| E2-XhoI | TTCTCGAGGGCTCCTTGGAAGCTGTCAGT | |

| vicKP1 | TTACCAGATGCTTTTGTTGCT | Position 268 upstream of vicK to bp 288 of vicK |

| vicKP2-AscI | TTGGCGCGCCTACAGACGGTTTTTCTCCTGTG | Position 268 upstream of vicK to bp 288 of vicK |

| vicKP3-XhoI | TTCTCGAGGTGACCGTTTTTATCGTGTTG | Position 1156 of vicK to bp 421 downstream of vicK |

| vicKP4 | CTCTTGCCGTCTTTCATCAG | Position 1156 of vicK to bp 421 downstream of vicK |

| vicRHisF-NcoI | AACCATGGAGAAAATTCTAATCGTTGACGA | 717-bp vicR ORF for His tag fusion |

| vicRHisR-XhoI | AACTCGAGGTCATATGATTTCATGTAATAAC | 717-bp vicR ORF for His tag fusion |

| SMU.22 (gbpB) | TTGACAGCTTATCCTTTAAATG | 223 bp upstream to position 87 |

| TTTACAGCTGATAATGTTGTCG | 223 bp upstream to position 87 | |

| SMU.1005 (gtfC) | GATGCTAACTCTGGAGAACGA | 231 bp upstream to position 99 |

| TCCTGAAAGAGAGGTCAAAGTC | 231 bp upstream to position 99 | |

| SMU.1924 (covR) | AGATGTCCTCTACCCATTGAAAAATGG | 269 bp upstream to position 87 (9) |

| AACCTCATATCCTTCATGTTGTAATTCTAAAG | 269 bp upstream to position 87 (9) |

Restriction sites are underlined. Erm, erythromycin.

Construction of inducible gbpB RNA antisense system.

A shuttle vector was constructed to express the gbpB antisense sequence under the control of the inducible TetO/TetR promoter, as previously described (53). The promoter sequence was obtained by PCR from plasmid pACL2073, kindly provided by Ambrose L. Cheung (Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, NH), by use of primers pTet5 and pTet6 (53). This sequence was cloned into pMM223 at EcoRII and BglII sites, generating plasmid pTet. The TetO/TetR fragment obtained from digestion of pTet with EcoRI and BglII was cloned into pMM223 at EcoRI-BglII sites, resulting in pTetE. A 242-bp amplicon corresponding to the N-terminal sequence of GbpB (ASGbpB fragment) was obtained by PCR with primers ASGbpBF and -R. The amplicon was digested with KpnI and cloned in the antisense orientation into pTetE, generating plasmid ptetASGbpB, which was transformed into S. gordonii strain Challis. This vector was amplified in one of the transformed Challis strains (CA2) selected in TSA with erythromycin. The correct insertion of the antisense gbpB sequence in relation to the TetO/TetR promoter was verified by PCR using primers TetF and ASGbpbF, and amplicons of the expected sizes were validated by sequencing. Plasmid ptetASGbpB was purified from CA2 by alkaline lysis and transformed into S. mutans UA159, as described elsewhere (36). Transformants were selected and maintained in BHI with erythromycin. The clone carrying the correct ptetASGbpB plasmid was designated UACA2. A UA159 strain containing the pMM223 empty plasmid was designated UA223. Strains UA159 and UA223 were used as controls.

Induction of antisense gbpB RNA.

Optimal conditions for gbpB downregulation were determined by quantifying cell-associated and secreted GbpB in strains UACA2, UA223, and UA159 by Western blotting. Cultures of each strain (A550, 0.4) were treated with 0, 100, 150, and 200 ng/ml dox for 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 h of antisense induction at 37°C (10% CO2, 90% air). Reductions in growth yield were observed previously for 18-h cultures of UA159 in BHI with 200 ng/ml dox (mean A550, 0.82; standard deviation [SD], 0.03) compared to cultures in BHI only (mean A550, 0.93; SD, 0.06); these results were similar in extent to those reported in a previous study with S. mutans LT11 (53). The greatest reductions in cell-associated and secreted GbpB were obtained after 2 h of induction of ASgbpB with 200 ng/ml dox. These reductions were sustained for up to 3 to 4 h of dox exposure, but some variability was observed at later time points. Thus, in all further experiments, conditional mutant strain UACA2 was grown in BHI with erythromycin for 18 h, and then cultures were diluted in fresh medium (1:100) and incubated to an A550 of 0.4, at which point dox (200 ng/ml) was added and incubation was continued for 2 h. Samples of 1.5 to 3.0 ml of culture suspension were centrifuged (10,000 × g), and cell pellets as well as culture fluids were collected. Protein and RNA were extracted to quantify cell-associated GbpB and gbpB transcripts, respectively. Secreted GbpB was quantified in culture fluids. Cultures of control strains (UA159 and UA223) were also exposed to dox under the same conditions, and cells and culture fluids were collected and analyzed similarly.

Analysis of gbpB regulation by the VicRK TCS.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) to investigate direct regulation of gbpB by VicRK were performed as described previously (43), with some modifications. Briefly, to obtain a recombinant VicR (rVicR)-His fusion protein, the vicR open reading frame (ORF) was amplified with primers vicRHisF-NcoI and vicRHisR-XhoI (Table 1). The PCR fragment was digested with NcoI and XhoI, purified, and cloned into NcoI-XhoI-digested pET-22b(+) (Novagen) to yield pET-vicR. The plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21, and recombinant protein was isolated from 1 liter of culture (optical density at 550 nm [OD550], 0.8) after 3 h of induction with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). After cell lysis, recombinant protein was purified by affinity chromatography on Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen), eluted rVicR was dialyzed, and its purity and integrity were visualized by Coomassie blue staining. Purified protein was stored at −20°C. For EMSA, PCR amplicons obtained with the primers listed in Table 1 included putative promoter regions of gbpB and positive- and negative-control genes (gtfC and covR, respectively) end labeled with a DIG Gel Shift kit (Roche) and stored at −20°C. Promoter fragments (0.12 ng; ∼0.6 fmol) and increasing amounts of rVicR (0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 pmol) were incubated in reaction volumes of 25 μl (60 min, 25°C) in binding buffer [20 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.2% Tween 20 (wt/vol), 30 mM KCl, pH 7.6] (Roche). As nonspecific competitors, 1 μg poly(dC-dG), 1 μg poly(dA-dT), and 0.1 μg poly-l-lysine were included in each reaction mix, as recommended by the manufacturer. Protein-DNA complexes were separated by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis on 6% DNA retardation gels (Invitrogen) at 70 V for 3 h. Gels were electrotransferred to positively charged nylon membranes, and probes were cross-linked under UV light. Chemiluminescent signals were detected using digoxigenin (DIG) wash and block buffers according to the manufacturer's protocol (Roche). Specificity of binding was evaluated in competition assays with a 200-fold excess of the respective unlabeled probe.

Because there is a conserved VicR-binding sequence among Gram-positive species (TGTWAHNNNNNTGTWAH, where W is A or T and H is A, T, or C) (16), we examined gbpB promoter regions to identify a putative VicR box, with the help of Gibbs Motif Sampler (50) and AlignACE (21, 40).

Protein and RNA extraction.

Protein extracts were prepared from cells previously exposed to dox as described above. After being harvested (10,000 × g, 5 min), cells were washed twice in cold saline, suspended in 220 μl of 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0 (TE), and stored at −70°C until use. Mechanical disruption of frozen cells (in 350 μl of water) was carried out in a Mini-Bead Beater apparatus (Biospec) at maximum power (4 cycles of 60 s, with 1-min intervals on ice). Extracts were centrifuged (7,000 × g, 30 s), and supernatants containing cell proteins were stored at −70°C until use. Samples of culture fluids (1.0 ml) were also collected after centrifugation of cultures (10,000 × g, 4°C, 5 min), treated with 10 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and frozen at −70°C. Protein concentrations were determined using Bradford assay reagents (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA extraction was carried out using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), and samples were stored at −70°C until use. Purity and integrity of the RNA samples were determined by spectroscopy (A260/280), and the samples were analyzed in formaldehyde agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

Determination of GbpB production.

The effects of ASgbpB RNA induction on the expression of cell-associated and secreted GbpB were analyzed using Western blot assays. Proteins from cell extracts (8 μg) or culture fluids (15 μl) were resolved in 6% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as previously described (35). The amounts of GbpB in the volumes of culture fluids were within the linear range for GbpB detection by Western blotting, determined as described elsewhere (28). Membranes were washed, blocked overnight at 4°C in TBST, pH 7.6 (100 mM Tris-HCl, 0.25% Tween, 5.0% nonfat milk [Nestlé, Brazil]), and probed with rat antisera specific to GbpB or with sham-immunized sera (48), diluted (1:4,000) in the same buffer. After several washes in TBST, membranes were incubated with mouse anti-rat IgG conjugated with peroxidase (1:2,000). GbpB was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system (GE, Amersham Bioscience, United Kingdom). Digital images of the autographs were analyzed with a densitometer (Bio-Rad GS-700 imaging densitometer), and relative amounts of GbpB are expressed as arbitrary units for band intensities detected within a linear range of GbpB concentrations (28).

Transcriptional analysis.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) was used to quantify gbpB transcripts, expressed either as antisense RNA (ASgbpB) or as a sequence corresponding to the 3′ end of the ORF (CgbpB), i.e., transcribed from the chromosomal copy of the gene. GbpB transcripts were also determined for UAvicK by use of primers CGbpBF and -R (Table 1). Reverse transcription of experimental samples together with negative controls was carried out with 1 μg RNA, using Superscript III RT (Invitrogen) and a pool of cDNA obtained with random primers as described elsewhere (49). SYBR green PCR assays were performed with an iCycler system (Bio-Rad). Standard amplification and melting point product curves were obtained for each set of primers (ASGbpB, CGbpB, and 16S RNA primers). Expression levels of the genes tested were normalized to expression of the 16S rRNA gene of S. mutans (49). Assays were performed in duplicate with at least three independent RNA samples.

Electron microscopic analysis of cell morphology and biofilm formation phenotypes.

The effects of gbpB downregulation on cell morphology and the initial phases of biofilm formation were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Briefly, overnight cultures of mutant and control strains were cultured in BHI with or without erythromycin, diluted 100-fold in fresh medium, and incubated to an A550 of 0.4. All cultures were treated with 200 ng/ml dox for 2 h (37°C, 10% CO2). Cells were harvested by centrifugation as described above, washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and processed in microcentrifuge tubes for SEM analysis. To analyze cells in biofilms, 1.0-ml cultures at an A550 of 0.4 were transferred to 24-well culture plates containing sterile glass slides, followed by addition of 200 ng/ml dox. Plates were gently mixed and incubated under the same conditions for 2 h for biofilm formation during downregulation of gbpB. Biofilms were washed three times with PBS to remove nonadherent cells and then processed for SEM analysis. Similar experiments were performed with medium containing 1.0% sucrose. For SEM processing, bacteria adhering to slides were fixed with paraformaldehyde (3% in PBS, 1 h, 4°C). After three PBS washes, samples were incubated with 1% osmium tetroxide at room temperature (1 h) and then washed and dehydrated in ethanol. Dried samples were sputter coated with gold and analyzed with a scanning electron microscope (JSM 5600LV; JEOL, Japan).

Complementation of biofilm formation phenotypes with purified native GbpB.

Biofilm assays were performed during GbpB downregulation in medium supplemented with native GbpB purified from S. mutans culture fluids (pGbpB). The amount of exogenously added GbpB (20 μg/ml) was comparable to that secreted by wild-type strain UA159 grown to an approximately equivalent cell density under similar conditions. Thus, after UACA2 was grown in BHI with erythromycin for 18 h, cultures were diluted (1:100) in fresh medium containing erythromycin and dox (200 ng/ml), with or without pGbpB, and incubated for 2 h (37°C, 10% CO2) for bacterial adherence and biofilm growth. Control cells harvested from 3.0-ml planktonic cultures and biofilm cells were processed for SEM. Nonadherent cells from biofilm culture fluids were also processed and analyzed by SEM.

Cell hydrophobicity assays.

Cell surface hydrophobicities were determined using a previously described assay (19). Briefly, cultures of UA159, UA223, UACA2, and UAvicK were grown to an A550 of 0.4, exposed to dox as previously described, harvested (10,000 × g, 5 min), washed twice with PUM buffer (22.2 g K2HPO4·3H2O, 7.26 g KH2PO4, 1.8 g urea, 0.2 g MgSO4·7H2O per liter, pH 7.1), and resuspended in the same buffer to an A550 of 0.900. Bacterial suspensions (3 ml) were mixed with 400 μl of hexadecane and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. Suspensions were mixed twice for 30 s by vortexing, with intervals of 5 s, and allowed to stand for complete separation of inferior aqueous from hexadecane phases. Aqueous phases were removed for determination of the A550. Percentages of cells retained in the aqueous phase (in relation to the A550 values of respective suspensions without hexadecane, but treated similarly) were subtracted from 100% to express the percentage of hydrophobic cells. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate.

Autolysis assay.

The autolytic activities of strains were analyzed using a previously described assay (2), with some modifications. Briefly, cultures of strains UA159, UA223, UACA2, and UAvicK were grown to an A550 of 0.4 and exposed to dox for 2 h, as described above. Cells were centrifuged (10,000 × g, 5 min) and washed twice with PBS. Cell pellets were resuspended in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5, with 1 M KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 0.4% sodium azide) to an A550 of 0.4. Cell suspensions were incubated at 44°C to activate autolysins expressed by UA159, and autolysis was monitored spectrophotometrically (A550) for 12, 24, and 48 h. Because of the variability observed in these assays, especially with UAvicK, at least 5 independent experiments were performed for strain comparisons.

Sensitivity to antibiotics.

We investigated the sensitivity of UACA2 to antibiotics that affect cell wall synthesis (penicillin G), protein synthesis (thiostrepton and streptomycin), and DNA replication (ciprofloxacin) during gbpB downregulation in comparison with strains UA159, UA223, and UAvicK. The MIC of each antibiotic was measured for the parent strain UA159 grown on BHI agar with 0.0004 μg/ml to 1 mg/ml of each antibiotic after 48 h of incubation. MICs of penicillin G, thiostrepton, streptomycin, and ciprofloxacin were 0.035, 0.04, 60, and 1.4 μg/ml, respectively. Respective sublethal concentrations used for these antibiotics (0.02, 0.02, 40, and 1.2 μg/ml) were defined as the maximum concentrations below the MICs that supported growth of wild-type strain UA159 and were used to test the sensitivities of strains UACA2, UA159, UA223, and UAvicK. Overnight cultures in BHI or BHI-erythromycin were diluted 100-fold in fresh medium and incubated to an A550 of 0.4 before the addition of dox (200 ng/ml) and a sublethal concentration of each antibiotic. Incubation continued for an additional 2 h, and serial dilutions of cultures were plated on BHI agar containing the respective antibiotics at the same concentration as that of dox (200 ng/ml). Plates were incubated for 48 h (37°C, 10% CO2) to determine the CFU/ml. Cultures not exposed to antibiotics were used as controls.

Viability under osmotic and oxidative stress.

Osmotic stress conditions previously shown to induce gbpB expression in GS5 and UA159 (13, 30) were used to investigate the effects of gbpB downregulation on cell viability. Similar experiments were performed with UAvicK. Briefly, cultures of test and control strains were exposed to dox for 2 h, followed by addition of NaCl (0.5 M) and further incubation for 30 min. Serial dilutions of cultures were plated on BHI agar supplemented with and without dox to determine cell viability.

Because the VicRK system has been implicated in oxidative stress responses in S. mutans (43), the sensitivities of the conditional mutant UACA2, UAvicK, and control strains to hydrogen peroxide were tested as described elsewhere (20), with some modifications. Briefly, strains were grown and exposed to dox for 2 h, as described above, before addition of H2O2 (10 μM) and incubation for 1 h. A lethal dose of H2O2 (100 μM) was then added, and incubation was continued for another 30 min. Serial dilutions of cells were plated on BHI agar with 200 ng/ml of dox for determination of the CFU/ml. At least three independent experiments were performed.

Data analysis.

Cell morphologies were analyzed visually in SEM digital images obtained at magnifications of ×800, ×9,000, and ×13,000. Biofilm growth in the presence of sucrose was analyzed in SEM digital images at a magnification of ×1,300 for 32 predetermined areas (63 to 97 μm) equally distributed on each glass slide. Using ImageJ image processing and analysis software in Java (NIH [http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/index.html]), cell lengths were determined by linear measurement of cells from isolated chains in which division was at the stage where equatorial width was equal to or greater than cell length. Numbers of cells and/or microcolonies per field were also determined for biofilm images. Parametric analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by pairwise multiple comparisons (Tukey test) was used to compare gbpB expression levels (transcript levels and densitometric measurements of GbpB levels in Western blots). Biofilm formation, cell length, cell hydrophobicity, autolysis, and stress sensitivity were compared between UACA2, control strains, and/or strains complemented with pGbpB, using a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis or Mann-Whitney test.

RESULTS

Induction of gbpB antisense RNA leads to reduced expression of GbpB.

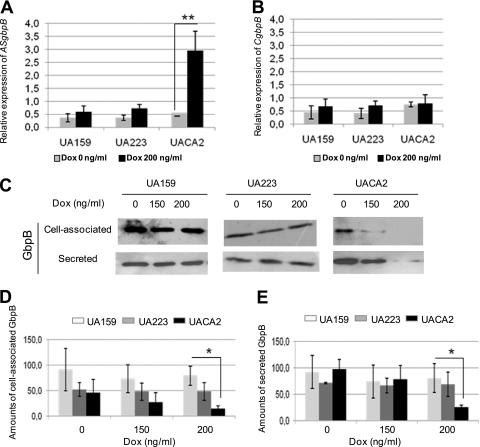

Induction of the TetO/TetR promoter in UACA2 grown with increasing concentrations of dox (0, 150, and 200 ng/ml) led to significant dose-dependent increases in the levels of ASgbpB transcripts. A 4.9-fold relative increase in ASgbpB was observed in conditional mutant strain UACA2 after a 2-h exposure to 200 ng/ml dox (UACA2-dox) compared to the same mutant (UACA2) grown in the absence of dox (Fig. 1A). Amounts of ASgbpB transcripts were significantly higher in UACA2-dox than in the UA159-dox or UA223-dox negative control (ANOVA) (P < 0.01). To confirm that these increases were not due to increased transcription of the chromosomal gene, we performed RT-PCR assays with the same samples, using primers for CgbpB, from the 3′ terminus of gbpB. Levels of CgbpB did not change significantly in UACA2-dox (Fig. 1B), confirming that high levels of ASgbpB transcripts in UACA2-dox resulted from induction of the TetO/TetR promoter in vector CA2. In addition, levels of ASgbpB transcripts in UA159-dox and UA223-dox were similar to those detected in UACA2 grown in the absence of dox (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Effects of expression of gbpB antisense RNA (ASgbpB) on suppression of GbpB production. (A) Relative expression of ASgbpB in conditional mutant UACA2 in response to 2 h of dox induction, determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Controls included wild-type strain UA159 and UA159 carrying an empty plasmid (UA223). **, P < 0.01 (ANOVA). (B) Relative levels of gbpB transcripts of chromosomal origin (CgbpB) after treatment with or without dox. (C) Representative Western blot analysis of levels of cell-associated and secreted GbpB in strains treated with increasing concentrations of dox. (D and E) Quantitative analysis of GbpB production in response to dox. Columns indicate means for three independent experiments, and error bars represent standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 (ANOVA).

Induction of ASgbpB transcription in UACA2-dox led to consistent reductions in the amounts of GbpB produced. Maximum reductions in cell-associated and secreted GbpB were obtained after a 2-h induction of UACA2 with 200 ng/ml of dox (Fig. 1C). Densitometric determination of the amount of GbpB revealed 5.5- to 3.2-fold reductions in the mean levels of cell-associated and secreted protein, respectively, in UACA2 compared to the parental strain (Fig. 1C, D, and E). In addition, total amounts of GbpB (the sum of densitometric measurements of cell-associated and secreted protein) in UACA2 were significantly lower than those produced by UA159 or UA223 (ANOVA and Tukey test; P < 0.05). GbpB production remained low after 3 and 4 h of dox exposure but increased progressively after 5 to 8 h of incubation in the presence of dox (data not shown).

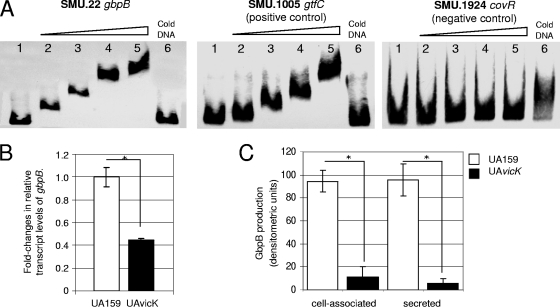

GbpB is regulated directly by the VicRK TCS.

Previously, it was shown that VicR binds to gtfB, gtfC, and ftf promoters in vitro and that expression of these genes and gbpB was reduced in a vicK mutant (43). Direct binding of VicR to the promoter of gbpB was not previously shown; by using EMSA (Fig. 2A), we established that recombinant VicR binds to gbpB promoter regions, leading to a shift in migration of similar extent to that observed for gtfC, a gene previously shown to bind VicR (43). Consistently, transcript levels of gbpB in UAvicK were approximately 60% lower than that in UA159 at the same growth phase (Fig. 2B), and amounts of cell surface and secreted GbpB were approximately 10-fold lower in UAvicK than in the wild-type strain (Fig. 2C), as revealed by the densitometry of GbpB bands detected by Western blotting. Thus, our data show that gbpB is regulated directly and positively by the VicRK TCS and that UAvicK expresses low levels of GbpB. Additionally, a putative VicR-binding sequence was identified in the gbpB promoter region (TGTAATAATGAcGTAAT [the lowercase letter indicates a mismatch]), which is located 7 bp upstream from the transcriptional start site.

FIG. 2.

(A) EMSA. Twenty-five-microliter DNA-binding reaction mixtures were prepared with end-labeled DNA fragments (∼0.6 fmol) from the 5′-proximal region of gbpB, gtfC, or covR and with purified His-tagged VicR. Lanes 1, no protein; lanes 2, 30 pmol of VicR; lanes 3, 60 pmol; lanes 4, 90 pmol; lanes 5, 120 pmol. Specific competitions were performed with 120 pmol VicR and a 200-fold excess of unlabeled DNA (lanes 6). The promoters of gtfC (known target of VicR) and covR (not regulated by VicR) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. (B) Reduction in gbpB transcript level in UAvicK relative to that in the wild-type strain. (C) Reductions in production of cell-associated and secreted GbpB in UAvicK relative to that in the wild-type strain. Amounts of protein are expressed as densitometric units of GbpB bands detected in Western blot assays. Columns represent means for three independent experiments, and error bars indicate standard deviations. *, P < 0.01 (ANOVA).

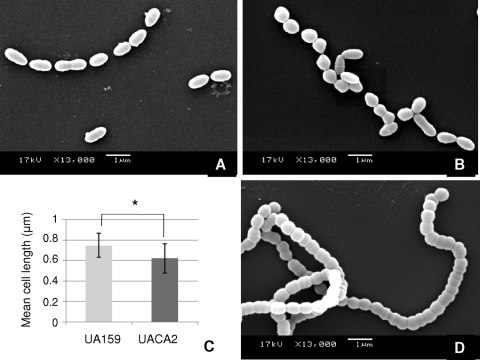

Different cell morphologies result from GbpB depletion and vicK mutation.

We examined the morphology of mid-log-phase cells (A550, 0.4) after exposure to dox (2 h) in BHI without sucrose. As depicted in Fig. 3 B, downregulation of GbpB in UACA2 promoted alterations in cell shape compared to control strains (Fig. 3A). These morphological analyses were repeated several times, and the results presented are representative of six independent experiments. Typically, the wild-type strain showed chains of cocci with a rod-like shape (Fig. 3A), while UACA2 formed chains of shorter cocci (Fig. 3B). To substantiate this qualitative analysis, we measured cell lengths of 200 cells from randomly selected isolated chains, determining mean cell lengths of 0.75 μm (SD, 0.11 μm) and 0.62 μm (SD, 0.14 μm) for strains UA159 and UACA2, respectively, following dox exposure (Fig. 3C); the median cell length of UA159-dox (0.75 μm; lower and upper quartiles, 0.67 and 0.81 μm, respectively) was significantly longer than the median cell length of UACA2-dox (0.63 μm; lower and upper quartiles, 0.52 and 0.70 μm, respectively) (Mann-Whitney test; P < 0.01). The differences in these two-dimensional measures between strains, although small, were observed consistently. No significant differences were observed when UACA2 grown in the absence of dox was compared with the wild-type strain (data not shown). Although the coccal morphology of UACA2-dox resembled that of the UAvicK mutant (Fig. 3D), the latter strain also formed extremely long chains (Fig. 3D) that were not observed in UACA2. These results indicated that depletion of GbpB expression (about 5-fold) influenced cellular morphology but did not affect chain formation as in UAvicK. Additionally, medium supplementation with exogenous pGbpB did not significantly restore the wild-type phenotype (data not shown), suggesting that GbpB may have to be cell associated in order to participate in cell wall morphogenesis.

FIG. 3.

Scanning electron microscopic analysis of cell morphology. Wild-type strain UA159 and UACA2 at mid-log phase (A550, 0.4) were exposed to dox (200 ng/ml) for 2 h before being processed. UAvicK was not exposed to dox. (A) Wild-type UA159. (B) UACA2. (C) Comparison of mean cell lengths. *, P < 0.01 (Mann-Whitney test). (D) UAvicK.

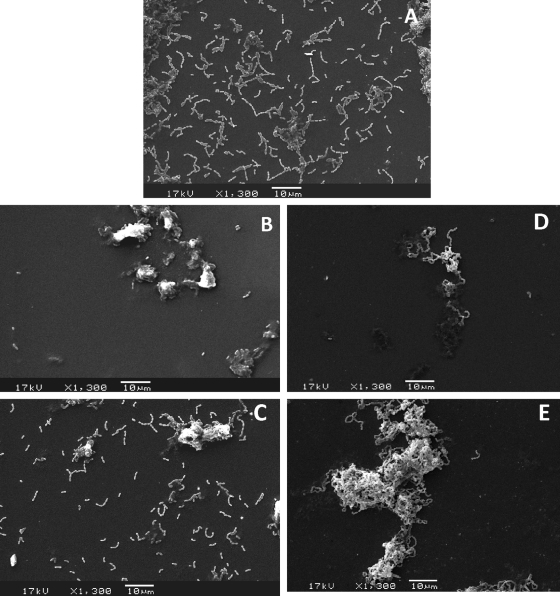

Downregulation of gbpB impairs sucrose-dependent biofilm formation.

Visual inspection of initial stages of biofilm growth in BHI containing 1.0% sucrose revealed that UA159-dox and UA223-dox or UACA2 grown in the absence of dox clearly formed homogeneous biofilm layers. In contrast, UACA2-dox and UAvicK were not able to cover slides but formed sparse compacted microcolonies that detached from the slides during rinsing. Analysis of SEM digital images of the initial stages of biofilm formation confirmed these visual observations; the levels of adhered cells or microcolonies determined for 32 predefined areas of each slide could be compared consistently between strains (total of 128 images analyzed per experiment). As depicted in Fig. 4 A, UA159 formed a homogeneous layer of primarily diplococcal chains or microcolonies on the glass surfaces (mean, 129.94 per area; SD, 30.4; median, 133), in that a continuous extracellular matrix could clearly be detected in intimate contact with cells. With a contrasting phenotype, UACA2 formed few microcolonies (mean, 33.75 per area; SD, 16.21; median, 32) that were distributed heterogeneously on the slides (Fig. 4B). These microcolonies contained an extracellular matrix but were of atypical structure. To confirm the effects of GbpB depletion on the biofilm growth phenotype, we performed experiments in which gbpB was downregulated in medium supplemented with native GbpB purified from S. mutans culture fluids (pGbpB). Addition of pGbpB to the medium partially restored biofilm formation (Fig. 4C), and biofilms acquired a wild-type phenotype. The number of cells or microcolonies per area for UACA2-dox with pGbpB (mean, 59.00; SD, 22.12; median, 67) was significantly higher than that observed for UACA2-dox (Kruskal-Wallis test; P < 0.01). In the UA159 strain background, inactivation of vicK altered the structure of 18-h mature biofilms in S. mutans (43), so we examined the initial phases of UAvicK biofilm formation in the presence of sucrose. Few microcolonies of UAvicK were observed per area (mean, 4.97; SD, 3.51; median, 4) compared to the other strains, but these were distinct from the UACA2-dox microcolonies in that they were formed by extremely long chains and were apparently devoid of extracellular matrix (Fig. 4D). Addition of exogenous pGbpB promoted a 2.1-fold increase in the number of microcolonies (mean, 10.44; SD, 5.80; median, 9) formed by UAvicK in comparison to UAvicK without pGbpB (Mann-Whitney U test; P < 0.01), and the size of microcolonies was apparently larger (Fig. 4E).

FIG. 4.

Scanning electron microscopic analysis of initial stages of biofilm formation (2 h) on the surfaces of glass slides in BHI with 1.0% sucrose. (A) Strain UA159 under exposure to dox. (B) Conditional mutant UACA2 under exposure to dox. (C) Same as in panel B, but in medium supplemented with native pGbpB. (D) Representative microcolony formed by UAvicK. (E) Representative microcolony formed by UAvicK in the presence of native pGbpB, showing the tendency of increasing sizes. This experiment is representative of at least four independent experiments.

GbpB downregulation affects S. mutans autolytic activity and hydrophobicity.

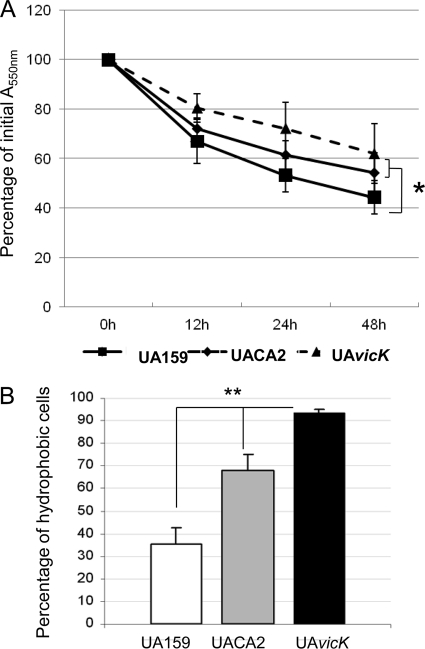

GbpB shares extensive similarity with murein hydrolases, including a CHAP domain commonly identified in autolysins which are important for cell surface biogenesis and adaptation during growth and, possibly, biofilm formation (2, 10). Therefore, we investigated the effects of gbpB downregulation on cell autolysis at high temperature and on cell hydrophobicity. The autolytic activities of strains, expressed as percentages of final A550 values with respect to initial A550 values, are shown in Fig. 5 A. Following incubation at 44°C, mean percentages of cells resistant to autolysis were 62.0, 54.4, 44.3, and 40.4% for strains UAvicK, UACA2-dox, UA159-dox, and UA223-dox, respectively. No significant difference in susceptibility to autolysis was observed between control strains UA159 and UA223 (Mann-Whitney test; P > 0.05). UAvicK and UACA2-dox were significantly more resistant to autolysis than the wild-type strain (Mann-Whitney test; P < 0.05). UAvicK was the most resistant to autolysis, although no significant difference in autolytic activities was observed between UAvicK and UACA2-dox (Mann-Whitney test; P > 0.05). Thus, inactivation of vicK and downregulation of gbpB increase resistance to autolysis.

FIG. 5.

(A) Autolysis of strains after 2 h of exposure to dox (200 ng/ml). Values represent means for five independent experiments, and error bars represent standard deviations. At 48 h of incubation, UACA2 and UAvicK showed lower reductions in initial absorbances than UA159. No significant difference was observed between UAvicK and UACA2. *, P < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney test). (B) Percentages of cells retained in the hydrophobic hexadecane phase in strains after exposure to dox. Columns represent means for three independent experiments, and error bars indicate standard deviations. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001 (Mann-Whitney test).

The results of hydrophobicity assays (Fig. 5B) indicated that depletion of GbpB caused a significant increase in hydrophobicity and that UAvicK was the most hydrophobic strain. After dox exposure, mean percentages of hydrophobic cells were 35.6% (SD, 0.07%) and 38.4% (SD, 0.09%) for UA159 and UA223, respectively; significantly higher percentages of UACA2 (mean, 67.8%; SD, 0.07%) and UAvicK (mean, 93.4%; SD, 0.02%) cells were retained in the hydrophobic phases.

GbpB depletion and vicK inactivation result in different sensitivities to antibiotics and osmotic and oxidative stresses.

The pcsB mutant of S. agalactiae is highly sensitive to antibiotics that affect different cellular functions (37, 38). Thus, the sensitivities of UACA2, UA223, UA159, and UAvicK to several antimicrobial agents were determined (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Reductions in the numbers of viable UACA2-dox cells exposed to drugs that target intracellular components (ciprofloxacin, streptomycin, and thiostrepton) were low and of similar magnitudes (1.18 to 1.53 log CFU/ml) to those for untreated controls (Mann-Whitney test; P < 0.001 to 0.05). A reduction of only 0.67 log CFU/ml was observed for UACA2 exposed to penicillin relative to the control level, and this difference did not achieve statistical significance. UAvicK was significantly more sensitive to ciprofloxacin (a reduction of 5.32 log CFU/ml of viable cells), and modest reductions in cell viability were observed for streptomycin, thiostrepton, and penicillin compared to the control levels (reductions of 0.42 and 0.71 log CFU/ml) (see Table S2). UA159 and UA223 also showed small reductions in cell viability in response to sublethal levels of each antibiotic.

Previously, gbpB was identified in a screen for genes that were upregulated in response to osmotic and acidic stresses (13); however, we did not observe consistent gbpB upregulation in response to these conditions in three strains tested (30). VicK has a conserved PAS domain that is typically involved in oxidative stress responses (43); therefore, we compared the sensitivities of UACA2, UAvicK, and control strains to osmotic and oxidative stresses. A 1.1-log reduction in the number of viable cells of UACA2 compared to control cells was observed after a 30-min exposure to 0.5 M NaCl (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The reduction in the number of viable cells of UACA2-dox following treatment with H2O2 (10 to 100 μM) was of a greater magnitude (2.72-log reduction in induced UACA2 exposed to oxidative stress compared to the control strain; P < 0.05 [Mann-Whitney test]). In general, UACA2 that was not stressed behaved similarly to control strains UA159 and UA223. Although UAvicK was sensitive to oxidative stress (reduction of 1.95 log CFU/ml compared to the control), the numbers were not statistically significant (Mann-Whitney test; P = 0.080) due to great variability between independent experiments. This variability might be explained in part by the formation of long chains by UAvicK, because fewer CFU were recovered from UAvicK cultures than from similar cultures of UACA2, which makes shorter chains. UAvicK showed a 1.09-log reduction in CFU/ml compared to the control after exposure to osmotic stress, and this difference was statistically significant (Mann-Whitney test; P < 0.01). Under the same experimental conditions, UA159-dox and UA223-dox were essentially unaffected by osmotic or oxidative stress.

DISCUSSION

Based on its affinity for polysaccharides, it was hypothesized that GbpB plays a role in virulence through biofilm development (28, 48), although the affinity of GbpB for glucans with alpha-1,6 glucosidic linkages is modest (47). gbpB is essential in several strains (30), and a gbpB mutant obtained from S. mutans strain GS5 was too fragile for further cultivation and study (J. S. Chia, personal communication), so the function of GbpB in S. mutans biofilm growth and/or virulence remains unexplored. A viable gbpB knockout mutant (designated BD1) was reported for strain MT8148 (17). However, Western blot analysis of strain BD1 and the parent strain MT8148 (kindly provided by Takashi Ooshima, Osaka University Graduate School of Dentistry, Osaka, Japan) revealed that expression of GbpB in BD1 was similar to that of MT8148 (data not shown). Furthermore, the gene product knocked out in BD1 was 100 kDa (27), while GbpB is 59 kDa (28, 45). Thus, we concluded that BD1 is not a bona fide gbpB knockout mutant.

In this study, we showed that downregulation of gbpB clearly altered the initial steps of sucrose-dependent biofilm formation (Fig. 4). These steps involve cell division and other physiological processes required for the transition from planktonic to biofilm growth (54). In S. mutans, extracellular polysaccharides derived from sucrose are essential for development and structure of microcolonies during the initial steps (2 to 8 h) of biofilm growth in vitro (55). The biofilm phenotype of the knockdown mutant UACA2 was partially restored by exogenous pGbpB (Fig. 4), suggesting that GbpB plays an extracellular function in biofilm formation. This limited restoration of biofilm growth by pGbpB may reflect reduced protein function under experimental conditions. For example, exogenous protein likely functions only during the initial steps of biofilm growth, because preformed polysaccharides might prevent pGbpB from gaining access to bacterial cell surfaces. While GbpB and PcsB are expressed in secreted and cell-associated forms (5, 28, 38), the functional relevance of expression in both forms is still unclear. The GbpB precursor protein has a 21-amino-acid signal peptide, but it does not have the LPTXG cell wall anchor motif (28). GbpB does not contain glucan-binding domains typical of Gtfs, GbpA, or GbpD and is not homologous to GbpC, a cell wall protein with glucan-binding properties (4, 41). However, GbpB has a conserved N-terminal domain containing a leucine zipper typically involved in protein-protein interactions and a C-terminal domain containing a CHAP motif associated with murein hydrolases (23, 28, 31).

The production of GbpB correlated positively with sucrose-dependent biofilm growth in vitro at 18 h of growth (28); similar associations were also observed for GtfB and GtfC but not for GtfD or GbpA (28, 29). In this study, we could not verify the effects of GbpB downregulation on mature 18-h biofilms, since gbpB downregulation could not be sustained for more than 5 to 8 h. Because of the apparently essential function of gbpB, unknown transcriptional and/or posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms might be activated to restore GbpB expression in the knockdown mutant (37). GbpB expression may also be controlled by posttranscriptional events, since increased expression of GbpB and other proteins involved in glucan-dependent virulence, e.g., GtfB, was observed in a mutant defective in HtrA protease (8), a protein which modulates adaptation to environmental stresses and expression of virulence factors (25, 39).

In the present study, we established that gbpB is part of the regulon of the VicRK TCS; VicR binds to the gbpB promoter region, possibly in the VicR box (5′-TGTAATAATGACGTAAT-3′), and deletion of vicK impairs GbpB expression at the RNA and protein levels (Fig. 2). Previously, it was shown that VicR directly regulates gtfB, gtfC, and ftf genes, implying the importance of this TCS in sucrose-dependent biofilm growth (43). VicR is an essential response regulator in several Gram-positive bacteria, including S. mutans (15, 43), and thus it is expected that vicR is still expressed in vicK mutants. Using Western blot assays, we observed that amounts of VicR produced by UAvicK were only about 10% of that produced by the wild-type strain UA159 (data not shown); thus, the role of VicK in the expression of its own cognate response regulator warrants further investigation. Here we observed that inactivation of vicK in UA159 impaired GbpB expression and altered biofilm formation, cell morphology, and different cell surface properties in a manner comparable to that observed when gbpB was downregulated, apart from some differences discussed below. UAvicK showed a poor ability to form biofilms on glass surfaces in the presence of sucrose, but the biofilm phenotype was different from that of UACA2-dox (Fig. 4). It was previously reported for an S. mutans vicK mutant that mature biofilms (grown for 16 h in sucrose medium) comprised long cell chains that detached at cellular junctions (43). Interestingly, in this study, we observed that addition of native pGbpB to the medium of UAvicK increased the number and size of microcolonies (Fig. 4), suggesting that extracellular GbpB may participate in cell-to-cell interactions.

In S. pneumoniae strain R6, 3- to 4-fold downregulation of pcsB transcripts promoted severe alterations in morphology and formation of long chains of ovoid cells (31), a phenotype that resembled the phenotype of the vicRKX conditional mutant, and it was proposed that the essentiality of the VicRK system was due to its role as a positive regulator of PcsB (31-33). In this study, we observed that UAvicK typically forms long chains of short spherical cells (Fig. 3D), as also observed for an S. mutans vicK mutant grown in biofilms (43). Although downregulation of gbpB promoted cells of spherical shape (Fig. 3B), long chains were not observed. Interestingly, the chain length phenotype associated with pcsB downregulation is strain dependent in S. pneumoniae (5), and pcsB depletion in encapsulated strain D39 leads to shortening of chains and spherical cells (5), a phenotype that resembles that of UACA2-dox. The effects of PcsB on S. pneumoniae morphogenesis were dependent on expression of capsular polysaccharide, controlled by the cps locus, since downregulation of pcsB in D39Δcps promoted a long-chain phenotype similar to that of the unencapsulated strain R6 (5). The influence of GbpB or PcsB depletion on phenotypes that are dependent on glucan or capsular polysaccharides might be reconciled by a model whereby synthesis of extracellular polysaccharides is coordinated with cell growth and cell surface biogenesis. Our working hypothesis is that GbpB participates in a glucan-dependent process of biofilm formation in which cell surface biogenesis, cell growth, and interaction with glucan are coordinated.

Despite a high similarity to murein hydrolases, such activity has not been detected with GbpB (28) or with purified PcsB proteins (5, 38). Murein hydrolases are an extensive group of enzymes with different specificities and redundant or complementary activities that frequently have more than one function (reviewed in reference 51). Most bacteria express murein hydrolases which participate in physiological processes that include cell wall turnover, cell separation, autolysis, competence, assembly of cell surface structures, and biofilm formation (51). In several bacterial species, VicRK regulates functions implicated in cell wall metabolism and synthesis of autolysins (15), and we are currently characterizing new genes directly regulated by the VicRK system whose products have putative roles in cell wall biogenesis in S. mutans (R. N. Stipp et al., unpublished data). The changes in autolytic activity and hydrophobicity observed in the gbpB knockdown mutant are further compatible with its protein homology with murein hydrolases and occurred in a mode similar to that of UAvicK, although to a lesser extent. S. mutans produces autolysins, which include AtlA and SmaA (SMU.609) (1, 11). AtlA also appears to be regulated by VicRK (3) and is involved in cell surface biogenesis and biofilm formation (1, 10). Thus, VicRK apparently regulates functions implicated in cell surface biogenesis in S. mutans, which may explain, in part, the more severe alterations in UAvicK phenotypes than in gbpB knockdown mutant phenotypes. The large increase in cell hydrophobicity promoted by vicK inactivation might account for the formation of cell aggregates previously reported for biofilms and broth cultures of a vicK mutant of UA159 (43). The aggregation of long chains likely accounts for the poor ability of UAvicK to initiate biofilms (Fig. 4). Although hydrophobicity was also promoted in UACA2-dox, this occurred to a lesser extent than that with UAvicK, and no aggregation of UACA2-dox short chains was detected (data not shown).

In GBS, inactivation of pcsB increases sensitivity to antibiotics which affect cytoplasmic and extracytoplasmic functions (37, 38), suggesting an increase in cell permeability. In S. pneumoniae, pcsB downregulation does not affect sensitivity to penicillin (5). GbpB downregulation for 2 h slightly increased the sensitivity of S. mutans to different antibiotics, promoting reductions in numbers of viable cells of 1 to 1.5 log. Differences exist in antibiotic and stress sensitivity phenotypes between UACA-dox and UAvicK. Unlike UACA2, UAvicK was clearly sensitive to ciprofloxacin. On the other hand, UACA2-dox was sensitive to oxidative stress, while reductions in cell viability under this stress were less evident for UAvicK. Antibiotic and oxidative stress sensitivity phenotypes of S. mutans vicK mutants are not consistent among studies, likely due to different experimental conditions (7, 14, 42-44). Given the essential function of GbpB, we cannot exclude the possibility that downregulation of GbpB in UACA2 and UAvicK promotes indirect effects on S. mutans physiology, thus accounting for the observed phenotypic changes.

In this study, we present experimental evidence that depletion of GbpB affects glucan-dependent biofilm formation and several cell surface properties. Some of these changes are similar to those observed in UAvicK, in accord with the role of VicRK as a direct regulator of gbpB. Further studies will be necessary to define the functional domains of GbpB and their role(s) in cell surface biogenesis and biofilm growth.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP; grants 07/56100-2 and 02/07156-1). C.D. was supported by FAPESP (grant 05/55775-0). R.N.S. was supported by FAPESP (06/55933-8). M.J.D. was supported by grants R01 DE15931 and R37 DE06153. D.J.S. was supported by grant R37 DE06153.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 November 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, S. J., and R. A. Burne. 2006. The atlA operon of Streptococcus mutans: role in autolysin maturation and cell surface biogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 188:6877-6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn, S. J., and R. A. Burne. 2007. Effects of oxygen on biofilm formation and the AtlA autolysin of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 189:6293-6302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn, S. J., Z. T. Wen, and R. A. Burne. 2007. Effects of oxygen on virulence traits of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 189:8519-8527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banas, J. A., and M. M. Vickerman. 2003. Glucan-binding proteins of the oral streptococci. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 14:89-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barendt, S. M., et al. 2009. Influences of capsule on cell shape and chain formation of wild-type and pcsB mutants of serotype 2 Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 191:3024-3040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bateman, B. T., N. P. Donegan, T. M. Jarry, M. Palma, and A. L. Cheung. 2001. Evaluation of a tetracycline-inducible promoter in Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and in vivo and its application in demonstrating the role of sigB in microcolony formation. Infect. Immun. 69:7851-7857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biswas, I., L. Drake, D. Erkina, and S. Biswas. 2008. Involvement of sensor kinases in the stress tolerance response of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 190:68-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biswas, S., and I. Biswas. 2005. Role of HtrA in surface protein expression and biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 73:6923-6934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biswas, S., and I. Biswas. 2006. Regulation of the glucosyltransferase (gtfBC) operon by CovR in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 188:988-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown, T. A., Jr., et al. 2005. A hypothetical protein of Streptococcus mutans is critical for biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 73:3147-3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catt, D. M., and R. L. Gregory. 2005. Streptococcus mutans murein hydrolase. J. Bacteriol. 187:7863-7865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chia, J. S., et al. 2001. A 60-kilodalton immunodominant glycoprotein is essential for cell wall integrity and the maintenance of cell shape in Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 69:6987-6998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chia, J. S., Y. Y. Lee, P. T. Huang, and J. Y. Chen. 2001. Identification of stress-responsive genes in Streptococcus mutans by differential display reverse transcription-PCR. Infect. Immun. 69:2493-2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng, D. M., M. J. Liu, J. M. Ten Cate, and W. Crielaard. 2007. The VicRK system of Streptococcus mutans responds to oxidative stress. J. Dent. Res. 86:606-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubrac, S., P. Bisicchia, K. M. Devine, and T. Msadek. 2008. A matter of life and death: cell wall homeostasis and the WalKR (YycGF) essential signal transduction pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 70:1307-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubrac, S., and T. Msadek. 2004. Identification of genes controlled by the essential YycG/YycF two-component system of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 186:1175-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujita, K., M. Matsumoto-Nakano, S. Inagaki, and T. Ooshima. 2007. Biological functions of glucan-binding protein B of Streptococcus mutans. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 22:289-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujiwara, T., et al. 1998. Molecular analyses of glucosyltransferase genes among strains of Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 161:331-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbons, R. J., and I. Etherden. 1983. Comparative hydrophobicities of oral bacteria and their adherence to salivary pellicles. Infect. Immun. 41:1190-1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higuchi, M., et al. 1999. Functions of two types of NADH oxidases in energy metabolism and oxidative stress of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 181:5940-5947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes, J. D., P. W. Estep, S. Tavazoie, and G. M. Church. 2000. Computational identification of cis-regulatory elements associated with groups of functionally related genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Mol. Biol. 296:1205-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lau, P. C., C. K. Sung, J. H. Lee, D. A. Morrison, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2002. PCR ligation mutagenesis in transformable streptococci: application and efficiency. J. Microbiol. Methods 49:193-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Layec, S., B. Decaris, and N. Leblond-Bourget. 2008. Characterization of proteins belonging to the CHAP-related superfamily within the Firmicutes. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 14:31-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynch, D. J., T. L. Fountain, J. E. Mazurkiewicz, and J. A. Banas. 2007. Glucan-binding proteins are essential for shaping Streptococcus mutans biofilm architecture. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 268:158-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyon, W. R., and M. G. Caparon. 2004. Role for serine protease HtrA (DegP) of Streptococcus pyogenes in the biogenesis of virulence factors SpeB and the hemolysin streptolysin S. Infect. Immun. 72:1618-1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macrina, F. L., J. A. Tobian, K. R. Jones, R. P. Evans, and D. B. Clewell. 1982. A cloning vector able to replicate in Escherichia coli and Streptococcus sanguis. Gene 19:345-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto-Nakano, M., K. Fujita, and T. Ooshima. 2007. Comparison of glucan-binding proteins in cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 22:30-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mattos-Graner, R. O., et al. 2001. Cloning of the Streptococcus mutans gene encoding glucan binding protein B and analysis of genetic diversity and protein production in clinical isolates. Infect. Immun. 69:6931-6941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mattos-Graner, R. O., M. H. Napimoga, K. Fukushima, M. J. Duncan, and D. J. Smith. 2004. Comparative analysis of Gtf isozyme production and diversity in isolates of Streptococcus mutans with different biofilm growth phenotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4586-4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattos-Graner, R. O., K. A. Porter, D. J. Smith, Y. Hosogi, and M. J. Duncan. 2006. Functional analysis of glucan binding protein B from Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 188:3813-3825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ng, W. L., K. M. Kazmierczak, and M. E. Winkler. 2004. Defective cell wall synthesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae R6 depleted for the essential PcsB putative murein hydrolase or the VicR (YycF) response regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1161-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng, W. L., et al. 2003. Constitutive expression of PcsB suppresses the requirement for the essential VicR (YycF) response regulator in Streptococcus pneumoniae R6. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1647-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng, W. L., H. C. Tsui, and M. E. Winkler. 2005. Regulation of the pspA virulence factor and essential pcsB murein biosynthetic genes by the phosphorylated VicR (YycF) response regulator in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 187:7444-7459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nogueira, R. D., et al. 2007. Age-specific salivary immunoglobulin A response to Streptococcus mutans GbpB. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14:804-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nogueira, R. D., A. C. Alves, M. H. Napimoga, D. J. Smith, and R. O. Mattos-Graner. 2005. Characterization of salivary immunoglobulin A responses in children heavily exposed to the oral bacterium Streptococcus mutans: influence of specific antigen recognition in infection. Infect. Immun. 73:5675-5684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perry, D., and H. K. Kuramitsu. 1981. Genetic transformation of Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 32:1295-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reinscheid, D. J., K. Ehlert, G. S. Chhatwal, and B. J. Eikmanns. 2003. Functional analysis of a PcsB-deficient mutant of group B streptococcus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 221:73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinscheid, D. J., B. Gottschalk, A. Schubert, B. J. Eikmanns, and G. S. Chhatwal. 2001. Identification and molecular analysis of PcsB, a protein required for cell wall separation of group B streptococcus. J. Bacteriol. 183:1175-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rigoulay, C., et al. 2005. Comparative analysis of the roles of HtrA-like surface proteases in two virulent Staphylococcus aureus strains. Infect. Immun. 73:563-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roth, F. P., J. D. Hughes, P. W. Estep, and G. M. Church. 1998. Finding DNA regulatory motifs within unaligned noncoding sequences clustered by whole-genome mRNA quantitation. Nat. Biotechnol. 16:939-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato, Y., Y. Yamamoto, and H. Kizaki. 1997. Cloning and sequence analysis of the gbpC gene encoding a novel glucan-binding protein of Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 65:668-675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Senadheera, D., et al. 2009. Inactivation of VicK affects acid production and acid survival of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 191:6415-6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Senadheera, M. D., et al. 2005. A VicRK signal transduction system in Streptococcus mutans affects gtfBCD, gbpB, and ftf expression, biofilm formation, and genetic competence development. J. Bacteriol. 187:4064-4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senadheera, M. D., et al. 2007. The Streptococcus mutans vicX gene product modulates gtfB/C expression, biofilm formation, genetic competence, and oxidative stress tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 189:1451-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith, D. J., H. Akita, W. F. King, and M. A. Taubman. 1994. Purification and antigenicity of a novel glucan-binding protein of Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 62:2545-2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith, D. J., W. F. King, H. Akita, and M. A. Taubman. 1998. Association of salivary immunoglobulin A antibody and initial mutans streptococcal infection. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 13:278-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith, D. J., W. F. King, and M. A. Taubman. 1995. Synthesis, cellular distribution and immunogenicity of S. mutans glucan-binding protein (GbpB59). J. Dent. Res. 74:123.

- 48.Smith, D. J., and M. A. Taubman. 1996. Experimental immunization of rats with a Streptococcus mutans 59-kilodalton glucan-binding protein protects against dental caries. Infect. Immun. 64:3069-3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stipp, R. N., R. B. Goncalves, J. F. Hofling, D. J. Smith, and R. O. Mattos-Graner. 2008. Transcriptional analysis of gtfB, gtfC, and gbpB and their putative response regulators in several isolates of Streptococcus mutans. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 23:466-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson, W., E. C. Rouchka, and C. E. Lawrence. 2003. Gibbs Recursive Sampler: finding transcription factor binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3580-3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vollmer, W., B. Joris, P. Charlier, and S. Foster. 2008. Bacterial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:259-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vriesema, A. J., R. Brinkman, J. Kok, J. Dankert, and S. A. Zaat. 2000. Broad-host-range shuttle vectors for screening of regulated promoter activity in viridans group streptococci: isolation of a pH-regulated promoter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:535-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang, B., and H. K. Kuramitsu. 2005. Inducible antisense RNA expression in the characterization of gene functions in Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 73:3568-3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Welin, J., J. C. Wilkins, D. Beighton, and G. Svensater. 2004. Protein expression by Streptococcus mutans during initial stage of biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3736-3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiao, J., and H. Koo. 2010. Structural organization and dynamics of exopolysaccharide matrix and microcolonies formation by Streptococcus mutans in biofilms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 108:2103-2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.