Abstract

Flaviviruses require complementarity between the 5′ and 3′ ends of the genome for RNA replication. For mosquito-borne flaviviruses, the cyclization sequences (CS) and upstream of AUG region (UAR) elements at the genomic termini are necessary for viral RNA replication, and a third motif, the downstream of AUG region (DAR), was recently designated for dengue virus. The 3′ DAR sequence is also part of a hairpin (HP-3′SL), and both complementarity between 5′ and 3′ DAR motifs and formation of the HP-3′SL in the absence of the 5′ end are conserved among mosquito-borne flaviviruses. Using West Nile virus as a model, we demonstrate that 5′-3′ DAR complementarity and HP-3′SL formation are essential for viral RNA replication.

Flaviviruses have an approximately 11-kb-long RNA genome of positive polarity (see reference 10). The viral RNA encodes one open reading frame (ORF), and the resulting polyprotein is cleaved co- and posttranslationally into 3 structural (N-terminal) and 7 nonstructural (NS) (C-terminal) proteins. The ORF is flanked on both sites by untranslated regions (5′ and 3′ UTR), which contain several cis-acting RNA elements that regulate RNA translation and replication. A prerequisite for viral RNA replication is genome circularization, and two essential sequence motifs complementary between the 5′ and 3′ ends have been reported for mosquito-borne flaviviruses: the 5′-3′ cyclization sequences (CS) and 5′-3′ upstream of AUG region (UAR) elements (1-3, 8, 9, 14, 16-19, 22, 23). Recently, a third motif in the dengue virus (DENV) 5′ terminus, located downstream of the AUG region (DAR), was reported to be involved in RNA replication (7) and possibly genome circularization. The sequence at the 3′ genomic end complementary to the 5′ DAR motif (3′ DAR) also appeared to have a role in RNA replication, but the data were less conclusive than that for the 5′ DAR. Furthermore, the 3′ DAR sequence is involved in the formation of a small hairpin at the bottom of the 3′ stem-loop (HP-3′SL) in the absence of the 5′ end, and nucleotides within the loop of the HP-3′SL are further predicted to form a pseudoknot with nucleotides in the 3′SL (13). Although it has been implicated in DENV translation (4) and replication (1, 7, 21), the role of the HP-3′SL in flavivirus replication has not been definitely delineated.

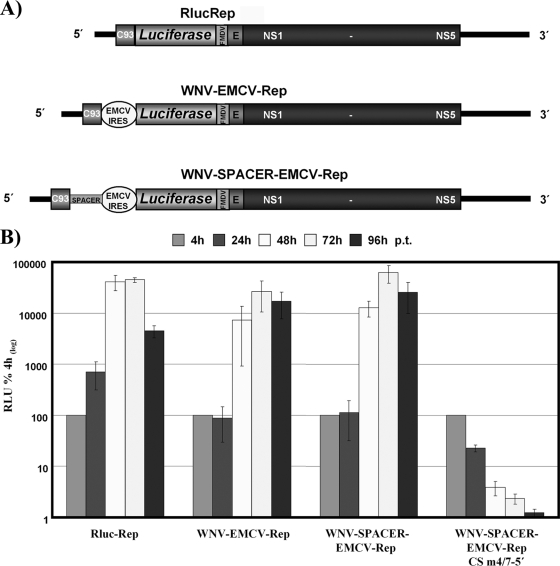

To further define the role of the DAR sequences and the HP-3′SL in RNA replication of mosquito-borne flaviviruses, we used West Nile virus (WNV) as a model, since to date nothing has been definitively determined about the impact of either of these motifs in WNV RNA replication. To study the effect of the 5′ DAR sequence on RNA replication, we modified a previously described WNV replicon (Fig. 1 A [RlucRep]) in which the structural proteins were replaced by the gene encoding Renilla luciferase (11). This resulted in WNV-EMCV-Rep and WNV-SPACER-EMCV-Rep (Fig. 1A), which have an overall design analogous to that of DENV replicons 5′UTR-Cap-tr and 5′UTR-Cap-tr-SPACER (7). In the case of WNV, the 5′ UTR and the first 93 capsid-coding nucleotides were present at the 5′ terminus, separated from an encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) internal ribosome entry site (IRES) by an engineered multiple cloning site or a multiple cloning site plus an ∼700-nucleotide-long sequence derived from the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene (Fig. 1A [WNV-EMCV-Rep and WNV-SPACER-EMCV-Rep]). This replicon design separates translational function from the WNV 5′ end, permitting analysis of the impact of the 5′ DAR sequence on RNA replication. The new replicons were tested for the ability to replicate in BHK cells over a time course of 96 h posttransfection (p.t.) as previously described (5, 7). Due to the slightly higher replication levels of WNV-SPACER-EMCV-Rep (Fig. 1B [compare WNV-EMCV-Rep to WNV-SPACER-EMCV-Rep]), we decided to use this backbone for all further analysis. To further demonstrate the functionality of the new replicon system, we tested a replicon with a mutation in the 5′ CS that was previously shown to abrogate RNA replication (Fig. 1B [WNV-SPACER-EMCV-Rep CS m4/7-5′]) (15) and confirmed inhibition of replication.

FIG. 1.

Characterization of WNV reporter replicon. (A) Schematic representation of the replicons used in this study. RlucRep has been described previously (11). In WNV-EMCV-Rep, the EMCV IRES is positioned downstream of the WNV 5′ end that contains the 5′ UTR and the first 93 nucleotides (nt) of the capsid coding region (C93), mediating translation of the Renilla luciferase (Luciferase) reporter gene and the viral ORF spanning the C-terminal sequence of E and NS1 to NS5. Luciferase is cleaved from the viral proteins by an engineered foot-and-mouth disease virus 2A (FMDV) cleavage site. 5′ and 3′ UTRs are indicated by black lines. In WNV-SPACER-EMCV-Rep, the WNV 5′ end and the EMCV IRES are separated by an approximately 700-nt-long spacer sequence derived from the GFP coding sequence (SPACER). (B) Replication competence of WNV reporter replicons over a time course of 96 h posttransfection (p.t.). Time points are indicated at the top of the panel, and relative light unit (RLU) values are expressed as percentages of the value measured 4 h p.t., which was set to 100%. The replicons RlucRep and WNV-SPACER-EMCV-Rep CS m4/7-5′ served as positive and negative controls, respectively. Results from at least three independent experiments are shown. Error bars reflect standard deviations.

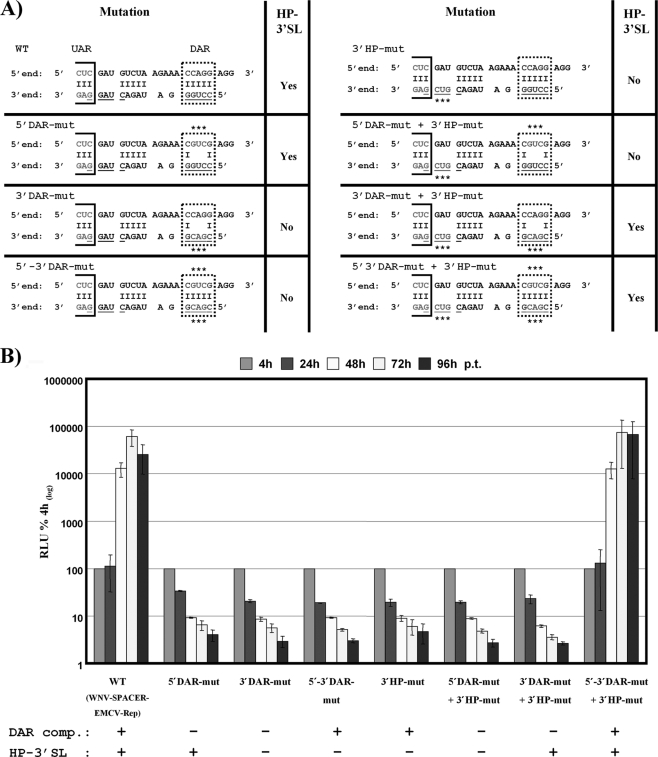

The positions of the DAR motifs in the 5′-3′ panhandle structure and the involvement of the 3′ DAR sequence in HP-3′SL formation were determined (see Fig. 4 [adapted from reference 6]). Mutations introduced in these RNA elements to disrupt or restore 5′-3′ DAR complementarity and/or formation of the HP-3′SL are summarized in Fig. 2 A. All mutants were tested in the WNV-SPACER-EMCV-Rep backbone for their ability to replicate in BHK cells over a time course of 96 h p.t. All mutations that eliminated 5′-3′ DAR complementarity and/or disrupted the HP-3′SL structure abrogated RNA replication (Fig. 2). However, restoring DAR complementarity and HP-3′SL formation restored RNA replication (Fig. 2A and B [5′-3′ DARmut + 3′HP-mut]), thus clearly demonstrating that both 5′-3′ DAR complementarity and the formation of the HP-3′SL are essential for WNV RNA replication. Replication levels were comparable to those of the parental WNV-SPACER-EMCV-Rep RNA, demonstrating that complementarity is more important than primary nucleotide sequence (Fig. 2B). Previous results derived using DENV replicons did not allow discrimination between effects of the primary sequence and nucleotide complementarity (7). Furthermore, no difference in translation efficiency at 4 h p.t. was detected (data not shown), indicating that the loss of RNA replication was not due to altered translation levels. Results that were similar but less conclusive regarding the role of the DENV DAR motifs and the HP-3′SL were recently reported (7).

FIG. 2.

Complementarity between the DAR sequences and the formation of the HP-3′SL are essential for WNV RNA replication. (A) Detailed overview of mutations introduced into the WNV-SPACER-EMCV-Rep replicon. The name of the mutant is indicated on the top left of each list of mutant data, and the positions and characters of the mutations are shown below on the predicted 5′-3′ interaction structure (a section between the UAR and the DAR sequences is shown). Complementary nucleotides between the 5′ and 3′ ends are indicated by a dash, and nucleotides at the 3′ end involved in HP-3′SL formation are underlined. The UAR motif is boxed, and the DAR motif is highlighted with a dashed frame. Mutations are indicated with an asterisk (*). A prediction with respect to formation of the HP-3′SL is included in the column with the heading “HP-3′SL” for each mutant. (B) Replication competence of variant WNV reporter replicons. Relative light unit (RLU) values were measured over a time course of 96 h after transfection of variant replicons harboring the mutations indicated below the graph. For more details, refer to the legend of Fig. 1B. Results from at least three independent experiments are shown. Error bars reflect standard deviations.

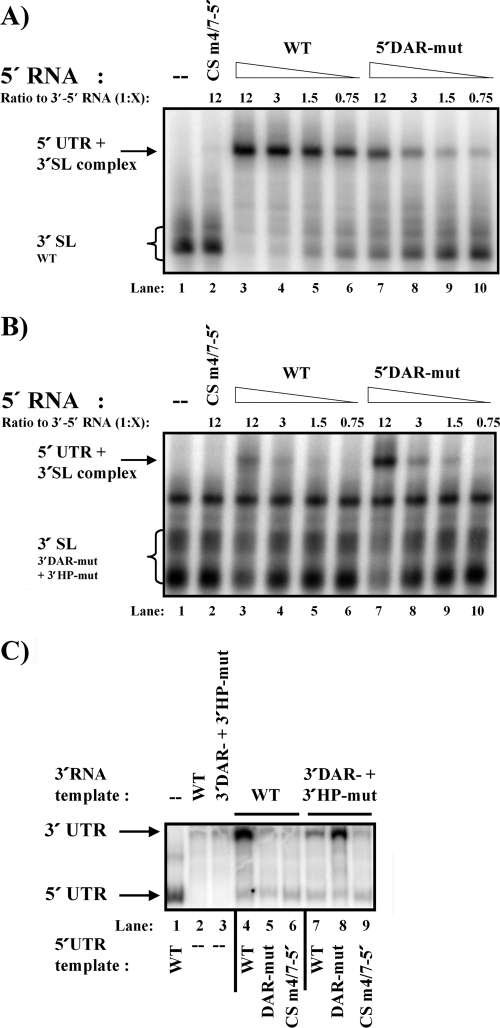

To analyze the direct impact of the WNV DAR motifs on 5′-3′ genome circularization, we used a previously described RNA binding assay in which interaction between two RNAs, one representing the 5′ end and the other the 3′ end, can be investigated (1, 3, 7, 22). For more details regarding the composition of RNAs used, please refer to the Fig. 3A and B legends. In vitro-transcribed RNAs (as described in reference 7) were subjected to heat denaturing and incubated alone or in combination, as indicated in Fig. 3, for 30 min at 37°C (7) in incubation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 μg freshly added tRNA). RNA complexes were analyzed by electrophoresis using 4.5% polyacrylamide gels supplemented with 5% glycerol as previously described (7). As previously shown (22), the 5′ wild-type (WT) RNA was able to form an RNA-RNA complex with the 3′ RNA, resulting in a shift of the radioactively labeled 3′ RNA (Fig. 3A, lane 3), whereas a 5′ RNA harboring a previously described mutation in the 5′ CS element abrogating RNA replication (CS m4/7-5′) (15) failed to shift the 3′ RNA (Fig. 3A, lane 2). Mutations in the 5′ DAR motif still resulted in an RNA-RNA interaction between the viral termini; however, the affinity was reduced 15- to 20-fold compared to the 5′-3′ WT RNA-RNA interaction (Fig. 3A; compare lane 6 [5′WT RNA with a 3′-to-5′ ratio of 1:0.75] to lane 7 [5′ DAR-mut RNA with a 3′-to-5′ ratio of 1:12]; the indicated bands were quantified as described previously [7]). Similarly, a mutation in the 3′ DAR (3′ DAR-mut + 3′HP-mut; Fig. 2A) disrupted the interaction with the WT 5′ RNA (Fig. 3B). Next, we restored DAR complementarity between the 5′ DAR-mut RNA and the 3′ RNA by the use of 3′ DAR-mut + 3′HP-mut; this restored the interaction between the RNAs derived from the viral termini (Fig. 3B; compare lanes 3 and 7). The band migrating between the 3′ SL and the 5′ UTR + 3′SL complex shown in the migration pattern in Fig. 3B might reflect the formation of a stable 3′SL RNA-RNA dimer formed under the conditions used, since when RNAs were electophoresed on a denaturing gel, only one RNA species was observed, indicating that the transcription reaction had proceeded as expected. Similar 3′ RNA-derived bands with a migration pattern unaffected by the addition of cold 5′ RNA have been previously reported for WNV and DENV (7, 22). To further analyze the impact of 5′-3′ DAR complementarity on genome cyclization and RNA replication, we performed an NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) in vitro activity assay as previously described (7) with purified WNV NS5 protein obtained from P.-Y. Shi et al. (6). The NS5 RdRp trans initiation assay reflected the RNA-RNA hybridization results in that the trans initiation activity of the WNV NS5 RdRp with respect to the 3′ UTR occurred efficiently only when DAR complementarity exists (Fig. 3C). Taken together, our results clearly show that 5′-3′ DAR complementarity is essential for WNV genome circularization, a prerequisite for RNA replication.

FIG. 3.

WNV 5′-3′ DAR complementarity is necessary for efficient RNA-RNA interaction and NS5 RdRp trans initiation in vitro. (A) RNA mobility shift analysis showing the effect of mutations within the 5′ DAR sequence on binding to the 3′ WT RNA. A detailed overview of mutations is presented in Fig. 2A. The 5′ RNA consists of the first 175 nt of the WNV genome, containing the mutations indicated along the top of the gel. The uniformly labeled 3′SL RNA includes the final 143 nt of the viral genome. The ratio between the 3′ and 5′ RNAs is indicated on top; “X” indicates the proportional amount by which the 5′ RNA exceeds the 3′ RNA. The mobility of the 3′SL alone or in complex with 5′ RNA is indicated on the left. The gel displayed is representative of the results of at least 3 independent experiments. (B) RNA mobility shift analysis showing the effect of mutations within the 3′ DAR sequence on binding to the indicated 5′ RNAs. The 5′ RNA consists of the first 160 nt of the WNV genome, containing the mutations indicated along the top of the gel. The uniformly labeled 3′SL RNA includes the final 113 nt of the viral genome, harboring the 3′ DAR-mut + 3′HP-mut mutation (Fig. 2A). (For more details, please refer to the panel A legend.) (C) Effects of 5′ and 3′ DAR mutations on RNA template usage and trans initiation of RNA synthesis by purified WNV NS5 (6). The gel displays the radiolabeled products from in vitro RdRp activity assays performed using recombinant WNV NS5. Mutations in the RNAs used as a template (0.5 μg each) are indicated above (3′ UTR RNA template, corresponding to the last 634 nt) and below (5′ UTR RNA template, corresponding to the first 160 nt) the gel. The migration patterns of the WNV 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR RNAs, as determined using the corresponding 5′ or 3′ in vitro-transcribed WT RNAs (not shown), are indicated on the left. Results displayed are representative of at least 5 independent experiments.

A recent publication indicated that NS5 binds to nucleotides in the 5′ DAR sequence and also protects nucleotides in the 3′ DAR in the 5′-3′ panhandle formation, indicating a role for the DAR elements in viral protein recruitment (6) and suggesting that complementarity between the viral termini might also be required for functions other than genome circularization.

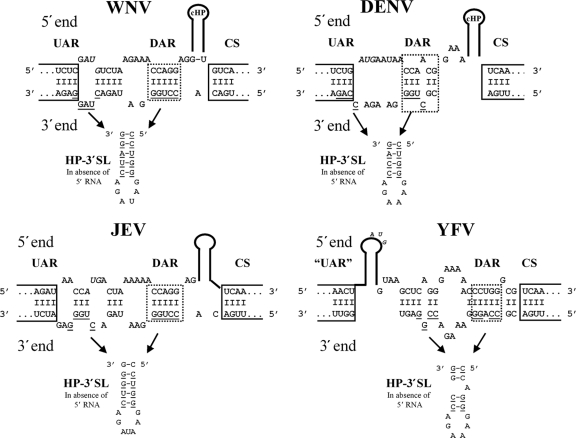

Since the DAR elements and the HP-3′SL, which includes sequences of the 3′ DAR motif, appear to be required for DENV (7) and WNV RNA replication, we compared published predictions of 5′-end-3′-end interactions as well as RNA structures of the 3′ genomic end in the absence of 5′ RNA in different mosquito-borne flaviviruses. A schematic overview of the predicted 5′-3′ panhandle and the HP-3′SL structure at the 3′ terminus of WNV (6), DENV (8, 9, 12, 13), yellow fever virus (YFV) (8, 9, 13), and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) (9, 20) is shown in Fig. 4. In all cases, the 5′ DAR is located downstream of the AUG and is predicted to base pair with the complementary 3′ DAR sequence, which forms part of the HP-3′SL in the absence of 5′ RNA. In WNV, DENV, and JEV, the 5′ DAR and 5′ CS elements are separated by a stem-loop structure, whereas for YFV, the 5′ DAR is predicted to be a direct extension of the 5′ CS element.

FIG. 4.

The DAR motif and the involvement of the 3′ DAR sequence in formation of the HP-3′SL are conserved among mosquito-borne flaviviruses. The predicted 5′-3′ RNA-RNA structures between the 5′-3′ UAR, 5′-3′ DAR, and 5′-3′ CS elements and the predicted HP-3′SL at the 3′ terminus in the absence of 5′ RNA for WNV (adapted from reference 6), DENV (adapted from references 8, 9, 12, and 13), JEV (adapted from references 9 and 20), and YFV (adapted from references 8, 9, and 13) are depicted. Sequences derived from the 5′ end are on top, and those from the 3′ end are on the bottom. RNA structures are indicated, the 5′-3′ UAR and 5′-3′ CS interactions are boxed, and the predicted DAR motif is highlighted with a dotted frame. Nucleotides involved in alternative stem formation at the 3′ end in the absence of 5′ RNA are underlined; the structure itself is displayed below in 3′-5′ orientation (“HP-3′SL In absence of 5′ RNA”). Complementarity between nucleotides is indicated by dashes.

The conservation of the HP-3′SL structure formation and the complementarity between the 5′ and 3′ DAR motifs in numerous mosquito-borne flavivirus serogroups, as well as our functional data derived using WNV, further support a model in which 5′-3′ circularization initiates between the 5′ and 3′ CS (12), after which the 5′-3′ DAR interaction extends the initial 5′-3′ CS end-to-end communication, thereby assisting the UAR elements, which also form a 5′-3′ duplex, to unwind the 3′SL (7). For DENV and WNV, one side of the HP-3′SL stem is composed of nucleotides derived from the 3′ DAR sequence, whereas the other stem side involves nucleotides that form part of the 3′ UAR motif (Fig. 4). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that once the 5′-3′ DAR interaction starts to form, the HP-3′SL melts and the 5′ region of the 3′ UAR sequence becomes accessible to the 5′ UAR. In turn, extension of the 5′-3′ UAR interaction stabilizes the 5′-3′ tertiary structure, resulting in a reorganization of the 3′SL. Although the 3′ UAR sequences are not part of the predicted HP-3′SL in the case of JEV and YFV, nucleotides involved in HP-3′SL formation are also predicted to interact with nucleotides in the 5′ end of the circularized genome and are likely to act similarly to the UAR sequences in DENV and WNV. We therefore propose that the 5′-3′ DAR motif and the HP-3′SL are important RNA elements required for RNA replication of mosquito-borne flaviviruses and that complementarity between the sequences is more important than the primary sequence, resulting in remodeling of the RNA structures at the 3′ end.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant AI052324.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarez, D. E., C. V. Filomatori, and A. V. Gamarnik. 2008. Functional analysis of dengue virus cyclization sequences located at the 5′ and 3′ UTRs. Virology 375:223-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez, D. E., et al. 2006. Structural and functional analysis of dengue virus RNA. Novartis Found. Symp. 277:120-132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez, D. E., M. F. Lodeiro, S. J. Luduena, L. I. Pietrasanta, and A. V. Gamarnik. 2005. Long-range RNA-RNA interactions circularize the dengue virus genome. J. Virol. 79:6631-6643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiu, W. W., R. M. Kinney, and T. W. Dreher. 2005. Control of translation by the 5′- and 3′-terminal regions of the dengue virus genome. J. Virol. 79:8303-8315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clyde, K., J. Barrera, and E. Harris. 2008. The capsid-coding region hairpin element (cHP) is a critical determinant of dengue virus and West Nile virus RNA synthesis. Virology 379:314-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong, H., B. Zhang, and P.-Y. Shi. 2008. Terminal structures of West Nile virus genomic RNA and their interactions with viral NS5 protein. Virology 381:123-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friebe, P., and E. Harris. 2010. Interplay of RNA elements in the dengue virus 5′ and 3′ ends required for viral RNA replication. J. Virol. 84:6103-6118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hahn, C. S., et al. 1987. Conserved elements in the 3′ untranslated region of flavivirus RNAs and potential cyclization sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 198:33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khromykh, A. A., H. Meka, K. J. Guyatt, and E. G. Westaway. 2001. Essential role of cyclization sequences in flavivirus RNA replication. J. Virol. 75:6719-6728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindenbach, B. D., H. J. Thiel, and C. M. Rice. 2007. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 1101-1152. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 11.Lo, M. K., M. Tilgner, K. A. Bernard, and P. Y. Shi. 2003. Functional analysis of mosquito-borne flavivirus conserved sequence elements within 3′ untranslated region of West Nile virus by use of a reporting replicon that differentiates between viral translation and RNA replication. J. Virol. 77:10004-10014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polacek, C., J. E. Foley, and E. Harris. 2009. Conformational changes in the solution structure of the dengue virus 5′ end in the presence and absence of the 3′ untranslated region. J. Virol. 83:1161-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi, P. Y., M. A. Brinton, J. M. Veal, Y. Y. Zhong, and W. D. Wilson. 1996. Evidence for the existence of a pseudoknot structure at the 3′ terminus of the flavivirus genomic RNA. Biochemistry 35:4222-4230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song, B. H., et al. 2008. A complex RNA motif defined by three discontinuous 5-nucleotide-long strands is essential for flavivirus RNA replication. RNA 14:1791-1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki, R., R. Fayzulin, I. Frolov, and P. W. Mason. 2008. Identification of mutated cyclization sequences that permit efficient replication of West Nile virus genomes: use in safer propagation of a novel vaccine candidate. J. Virol. 82:6942-6951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villordo, S. M., and A. V. Gamarnik. 2009. Genome cyclization as strategy for flavivirus RNA replication. Virus Res. 139:230-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoo, J. S., C. M. Kim, J. H. Kim, J. Y. Kim, and J. W. Oh. 2009. Inhibition of Japanese encephalitis virus replication by peptide nucleic acids targeting cis-acting elements on the plus- and minus-strands of viral RNA. Antiviral Res. 82:122-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.You, S., B. Falgout, L. Markoff, and R. Padmanabhan. 2001. In vitro RNA synthesis from exogenous dengue viral RNA templates requires long range interactions between 5′- and 3′-terminal regions that influence RNA structure. J. Biol. Chem. 276:15581-15591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.You, S., and R. Padmanabhan. 1999. A novel in vitro replication system for dengue virus. Initiation of RNA synthesis at the 3′-end of exogenous viral RNA templates requires 5′- and 3′-terminal complementary sequence motifs of the viral RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33714-33722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yun, S. I., Y. J. Choi, B. H. Song, and Y. M. Lee. 2009. 3′ cis-acting elements that contribute to the competence and efficiency of Japanese encephalitis virus genome replication: functional importance of sequence duplications, deletions, and substitutions. J. Virol. 83:7909-7930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng, L., B. Falgout, and L. Markoff. 1998. Identification of specific nucleotide sequences within the conserved 3′-SL in the dengue type 2 virus genome required for replication. J. Virol. 72:7510-7522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang, B., H. Dong, D. A. Stein, P. L. Iversen, and P. Y. Shi. 2008. West Nile virus genome cyclization and RNA replication require two pairs of long-distance RNA interactions. Virology 373:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang, B., H. Dong, D. A. Stein, and P. Y. Shi. 2008. Co-selection of West Nile virus nucleotides that confer resistance to an antisense oligomer while maintaining long-distance RNA/RNA base pairings. Virology 382:98-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]