Abstract

It has been reported that herpes simplex virus type 1 UL3, UL4, and UL20.5 proteins are localized to small, dense nuclear bodies together with ICP22 in infected cells. In the present study, we comprehensively characterized these interactions by subcellular colocalization, coimmunoprecipitation, and bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays. For the first time, it was demonstrated that both UL3 and UL20.5 are targeted to small, dense nuclear bodies by a direct interaction with ICP22, whereas UL4 colocalizes with ICP22 through its interaction with UL3 but not UL20.5 or ICP22. There was no detectable interaction between UL3 and UL20.5.

Of the 84 open reading frames (ORFs) of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) known to be expressed, more than half are functionally poorly understood and identified as encoding dispensable proteins for viral replication at least in some cell lines (21, 22). However, these ORFs appear to be essential for viral survival in nature, since viruses lacking these genes have not been isolated. Because mutant viruses lacking these genes have no obvious phenotype in infected cells, it remains difficult to functionally characterize these genes.

As an immediate-early protein, ICP22 appears to be essential for viral replication (5, 19). It localizes in the nucleus of infected cells and functions as a transcriptional repressor for both viral and cellular genes (5). Furthermore, ICP22 associates with transcriptional complexes containing the viral trans-activator protein ICP4, RNA polymerase II (4, 9, 14, 16), and other host factors, including cdc25C (25, 26) and cdk9 (7). Previous studies have reported that both UL3 and UL4 are expressed late in infection and are dispensable for viral replication in cultured cells in vitro (2, 8, 12). As a novel identified ORF situated between genes encoding UL20 and UL21 of the HSV-1 genome, the UL20.5 gene is not essential for growth and belongs to the γ2 kinetic class (27). Nevertheless, although the proteins encoded by these genes are dispensable for growth in cell culture, their functions are still unknown.

ICP22 localizes to small, dense nuclear structures early in infection, followed by the transition to the more diffuse replication complexes with nascent DNA and RNA polymerase II, ICP4, and other proteins associated with late gene transcription after the onset of viral DNA synthesis (11, 14). During later infection, ICP22 aggregates with UL3, UL4, and UL20.5 proteins as discrete, dense spots in the nucleus (11, 18, 27). However, deletion of ICP22 resulted in a decreased accumulation of UL3 and UL4, and neither UL3 nor UL4 localizes to the dense nuclear structures. Furthermore, ICP22 by itself is sufficient to form small, dense nuclear bodies in transfection assays without other viral proteins (18). Consequently, it was suggested that ICP22 may direct UL3 and UL4 to the dense nuclear structure (18). However, the interactions among the proteins of the UL3, UL4, UL20.5, and ICP22 complex remain elusive (11, 18, 27).

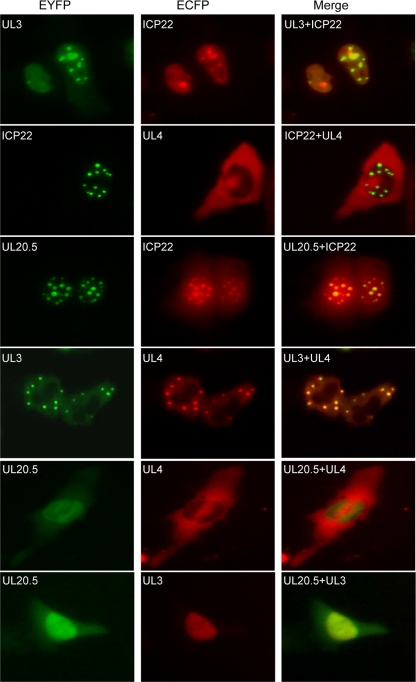

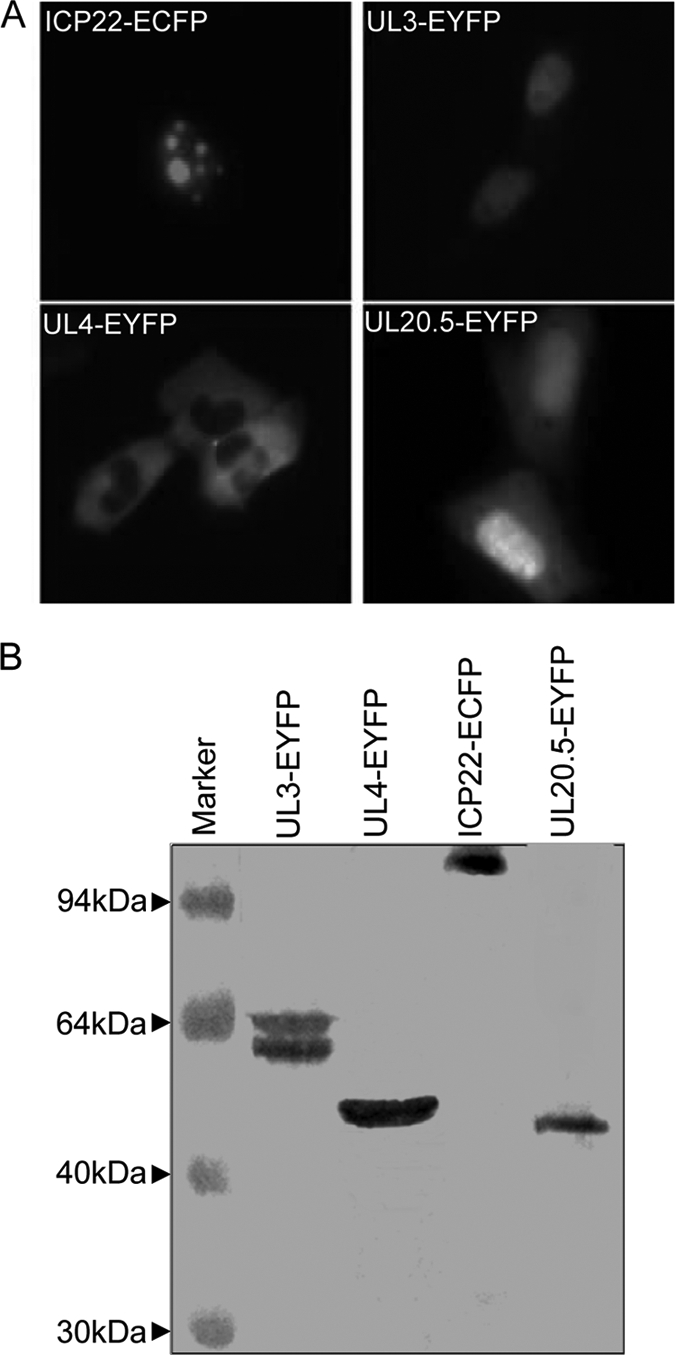

We first employed a subcellular colocalization assay to investigate the interactions of the four proteins in living cells. The plasmids encoding ICP22, UL3, UL4, and UL20.5 fused with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) or cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) were generated to examine their subcellular localizations. While expressed alone, ICP22-ECFP (enhanced CFP) targeted to small, dense nuclear structures (Fig. 1 A) similarly to its subcellular localization pattern during early and late HSV-1 infection (14). In contrast, UL3-EYFP (enhanced YFP) accumulated significantly in the nucleus, UL20.5-EYFP enriched in the nucleus with some diffuse distribution in the cytoplasm, and UL4-EYFP localized to subcytoplasmic structures (Fig. 1A). These fusion proteins were expressed at the expected size as confirmed by Western blot analysis using anti-YFP antibody (Santa Cruz) (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, coexpression of UL3-EYFP or UL20.5-EYFP with ICP22-ECFP displayed similar aggregation patterns, and UL3-EYFP or UL20.5-EYFP was redistributed to the nuclear foci with irregular shape and number and appeared to colocalize with ICP22-ECFP (Fig. 2), suggesting that both UL3 and UL20.5 might interact with ICP22. However, subcellular distribution of UL4 was not altered when it was coexpressed with ICP22 (Fig. 2). Similarly, neither UL3 nor UL20.5 was relocalized when coexpressed (Fig. 2). In addition, UL3 was relocated to the cytoplasm and colocalized with UL4 when coexpressed (Fig. 2), suggesting the possible interaction between UL3 and UL4.

FIG. 1.

Distinct subcellular localization of ICP22-ECFP, UL3-EYFP, UL4-EYFP, and UL20.5-EYFP fusion proteins in living cells. (A) Subcellular localization of the indicated fusion proteins. Representative images were taken under CFP and YFP filters in living COS-7 cells 24 h after transfection by fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss, Germany). Both fluorescent images of EYFP and ECFP fusion proteins were presented in pseudocolor, green and red, respectively. (B) Western blot analysis of the expressed fusion proteins using anti-YFP antibody.

FIG. 2.

Subcellular colocalization of ICP22, UL3, UL4, and UL20.5. COS-7 cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding the indicated fusion proteins. EYFP and ECFP fluorescence microscopy was performed in living cells 24 h after transfection. Both fluorescent images of EYFP and ECFP were presented in pseudocolor, green and red, respectively, and the merged images were shown to confirm the colocalization. Each image is a representative of the vast majority of the cells observed.

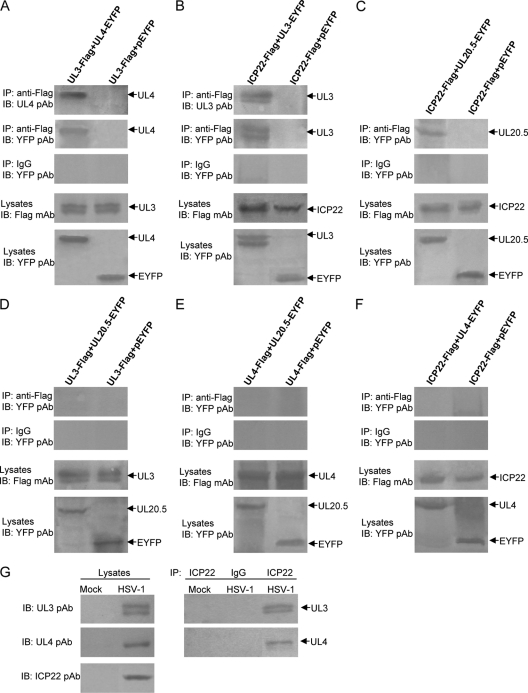

To further confirm the aforementioned interactions, a coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay was employed. Three Flag-tagged plasmids, namely, ICP22-Flag, UL3-Flag, and UL4-Flag, were constructed, and HEK293T cells were cotransfected with six pairs of plasmids, namely, UL3-Flag/UL4-EYFP, ICP22-Flag/UL3-EYFP, ICP22-Flag/UL20.5-EYFP, UL3-Flag/UL20.5-EYFP, UL4-Flag/UL20.5-EYFP, and ICP22-Flag/UL4-EYFP, for Co-IP analysis with anti-Flag monoclonal antibody (MAb). As expected, UL4-EYFP was successfully immunoprecipitated by anti-Flag MAb from cells expressing UL3-Flag and UL4-EYFP and was detected by both UL4 polyclonal antibody (pAb) (20) and YFP pAb. No detectable plasmid EYFP (pEYFP) was coimmunoprecipitated by anti-Flag MAb from cells coexpressing UL3-Flag and pEYFP (Fig. 3 A). As a negative control, mouse IgG failed to coimmunoprecipitate UL4-EYFP or EYFP. These results suggest that UL3 could interact with UL4 in vivo. Similarly, both UL3-EYFP and UL20.5-EYFP were efficiently coimmunoprecipitated from cells coexpressing ICP22-Flag/UL3-EYFP or ICP22-Flag/UL20.5-EYFP by anti-Flag MAb but not by nonspecific mouse IgG (Fig. 3B and C), suggesting that both UL3 and UL20.5 could interact with ICP22. In contrast, neither UL20.5-EYFP nor UL4-EYFP was coimmunoprecipitated from cells coexpressing UL3-Flag/UL20.5-EYFP, UL4-Flag/UL20.5-EYFP, and ICP22-Flag/UL4-EYFP by anti-Flag MAb or by nonspecific mouse IgG (Fig. 3D to F), suggesting that neither UL3 nor UL4 could interact with UL20.5 and that ICP22 may not interact with UL4 either. To determine whether the interaction complexes were present in HSV-1-infected cells, Vero cells were mock infected or infected with HSV-1(F) virus at a multiplicity of 5 PFU per cell. Twenty hours after infection, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblotting with rabbit anti-UL3 (15, 17), anti-UL4 (11, 20), and anti-ICP22 pAbs (1) or were immunoprecipitated with anti-ICP22 pAb followed by immunoblotting to detect UL3 and UL4 proteins. As expected, UL3, UL4, and ICP22 were expressed in cells infected with HSV-1(F) but were not detected in lysates of mock-infected cells (Fig. 3G). Importantly, both UL3 and UL4 proteins were coimmunoprecipitated with ICP22 (Fig. 3G). These results not only confirmed the interactions suggested by the subcellular colocalization analyses but also demonstrated that ICP22 may form interaction complexes with UL3 and UL4 in HSV-1-infected cells.

FIG. 3.

Confirmation of the interactions among HSV-1 ICP22, UL3, UL4, and UL20.5 by Co-IP assay. (A to F) HEK293T cells (2 × 106) were cotransfected with the indicated expression plasmids carrying a Flag or EYFP tag. Twenty-four hours after transfection, immunoprecipitation with anti-Flag monoclonal antibody (MAb) or nonspecific mouse antibody (IgG) was performed. (G) Vero cells were mock infected or infected with HSV-1(F) virus at a multiplicity of 5 PFU per cell. Twenty hours after infection, cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer, and coimmunoprecipitation was performed with rabbit anti-ICP22 polyclonal antibody (pAb) (1) or nonspecific rabbit antibody (IgG). Cell lysates and immunoprecipitated proteins were separated in denaturing 12% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The transferred proteins were probed with anti-YFP, anti-UL3 (15, 17), anti-UL4 (11, 20), or anti-ICP22 pAb. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblotting.

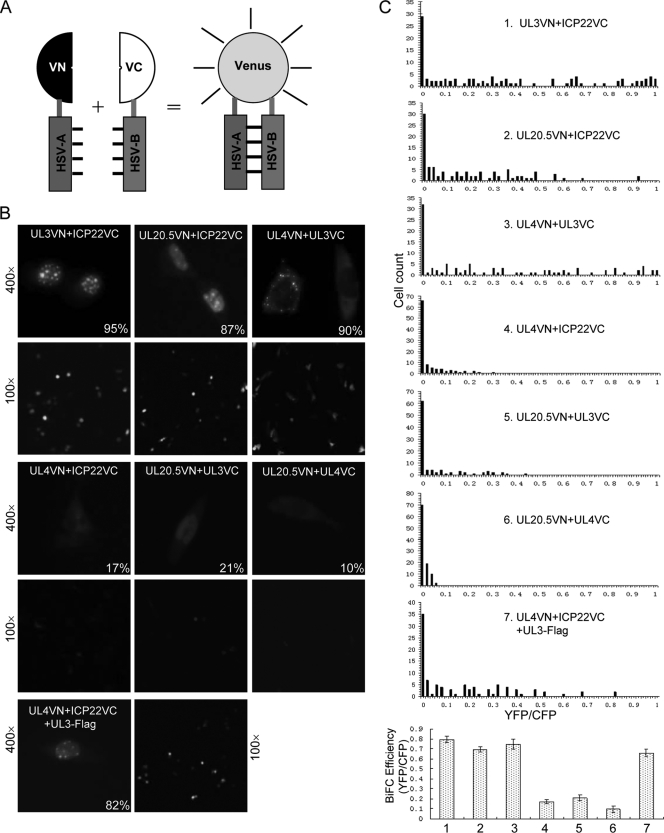

The bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay is a novel assay to visualize protein-protein interactions (10, 14, 23). The BiFC assay is based on the complementation between two nonfluorescent fragments of a fluorescent protein when they are brought close to each other by the interaction between proteins fused to the fragments (10, 13, 23) (Fig. 4A). One unique feature of the assay is to allow determination of subcellular locations of interacting complexes. To verify the subcellular localization of the interaction complex among ICP22, UL3, UL4, and UL20.5 in living cells, we coexpressed these proteins as fusions with either the N or C terminus of Venus (VN or VC, respectively) and performed BiFC analysis (23). Coexpression of UL3-VN and ICP22-VC, UL20.5-VN and ICP22-VC, or UL4-VN and UL3-VC resulted in a large number of cells with strong fluorescence (Fig. 4B and C). Importantly, the subcellular localization patterns of the fluorescence results were identical to those identified by the colocalization assay (Fig. 4B and 2), confirming that these interactions indeed relocalize the respective proteins to distinct locations. In contrast, only a small number of cells showed weak fluorescence when UL4-VN and ICP22-VC, UL20.5-VN and UL3-VC, or UL20.5-VN and UL4-VC were coexpressed (Fig. 4B and C). Additionally, the quantified BiFC efficiency data allowed for a direct comparison of BiFC efficiencies among seven experimental groups (Fig. 4C, bottom). The weak fluorescence that could result from the nonspecific association of VN and VC (23) (Fig. 4B and C) and the fact that these three pairs of proteins are not colocalized (Fig. 2) further confirm that these three pairs of proteins do not interact (Fig. 3).

FIG. 4.

Verification of the subcellular localization of the interaction complex among ICP22, UL3, UL4, and UL20.5 by BiFC analysis in living cells. (A) Schematic illustration of the BiFC assay for visualization of HSV protein interactions. HSV-A and HSV-B refer to two proteins encoded by HSV, and VN and VC are N- and C-terminal fragments of Venus, respectively. (B) Visualization of the subcellular localization of the interactions of ICP22, UL3, UL4, and UL20.5 in living cells by BiFC assay. COS-7 cells were cotransfected with 0.5 μg of each BiFC plasmid encoding the indicated fusion protein along with 0.1 μg of the pECFP plasmid. Eighteen hours after transfection, fluorescent images were taken using YFP and CFP filters under a magnification of ×400 and ×100, respectively. The numbers in the fluorescence images indicate the percentages of cells showing the representative subcellular localization. (C) Quantification of BiFC efficiency. BiFC efficiency was quantified from the transfected cells described in the legend to panel B by dividing the reconstituted Venus fluorescence (YFP) by the internal control CFP fluorescence for each individual cell. The number of fluorescent cells was plotted as a function of BiFC efficiency (YFP/CFP) as described previously (24). The quantified BiFC efficiency determined as the average of median values from three independent experiments is presented in the bottom chart.

Previous studies suggested that UL3 and UL4 targeted to the small, dense nuclear compartment late in infection with ICP22, which was dependent on their direct interaction with ICP22 (19). However, UL4 did not appear to interact with ICP22 based on our colocalization, Co-IP, and BiFC analyses, although UL4 could be coimmunoprecipitated with ICP22 from HSV-1-infected cells. Because UL4 and UL3 interact with each other, we speculated that UL3 may mediate the colocalization of ICP22 and UL4. To test this, we coexpressed UL4-VN and ICP22-VC in the presence of UL3-Flag. Indeed, we observed that strong fluorescence was accumulated in the nuclear dense bodies (Fig. 4B and C), demonstrating that UL4 accumulated in discrete patches in the nucleus through its interaction with UL3 but not direct interaction with ICP22.

Recently, the Us1.5 protein has been reported to be expressed from its own transcript, which initiates with the ICP22 ORF at codon 90 (6). Both ICP22 and Us1.5 localize to the nuclei of infected cells, and ICP22 localizes in small, dense nuclear structures early in infection (9). With the onset of viral DNA synthesis, these structures then shift to replication complexes containing nascent DNA, ICP4, and RNA polymerase II (11, 14). Late in infection, ICP22 distributes in the small, dense nuclear structures again along with three late proteins, namely, UL3, UL20.5, and UL4. Recently, it was demonstrated that the small, dense nuclear bodies containing ICP22 were VICE (virus-induced chaperone-enriched) domains, which also contain Hsc70, UL6, and components of the proteasome complex (3). Surprisingly, ICP22 and Hsc70 could not be coimmunoprecipitated (3). We speculate that Hsc70 may target to the VICE domain via interactions with other viral proteins (e.g., UL3 or UL20.5) and may play important roles in the formation of the interaction complex. Although the function of the small, dense nuclear bodies late in infection is less well understood, the observation that ICP22 relocates the newly synthesized UL3, UL20.5, and UL4 proteins directly or indirectly to such structures suggests that they may play a role in the viral replication cycle late in infection. Based on our analysis here, we suggest that ICP22 may act as a scaffold to assemble transcriptional regulatory proteins in the small, dense nuclear bodies to modulate gene expression of both host and viral genes. Taken together, these findings are of importance for further study of the function of the three late proteins and the small, dense nuclear compartments formed late in infection.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (grants 2010CB530105 and 2011CB504802), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 30900059, 30870120, and 81000736), and the Start-Up Fund of the Hundred Talents Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant 20071010-141).

We thank Bernard Roizman for his generous gifts of anti-UL3, anti-UL4, and anti-ICP22 polyclonal antibodies.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackermann, M., M. Sarmiento, and B. Roizman. 1985. Application of antibody to synthetic peptides for characterization of the intact and truncated alpha 22 protein specified by herpes simplex virus 1 and the R325 alpha 22 deletion mutant. J. Virol. 56:207-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baines, J. D., and B. Roizman. 1991. The open reading frames UL3, UL4, UL10, and UL16 are dispensable for the replication of herpes simplex virus 1 in cell culture. J. Virol. 65:938-944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastian, T. W., C. M. Livingston, S. K. Weller, and S. A. Rice. 2010. Herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein ICP22 is required for VICE domain formation during productive viral infection. J. Virol. 84:2384-2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bastian, T. W., and S. A. Rice. 2009. Identification of sequences in herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP22 that influence RNA polymerase II modification and viral late gene expression. J. Virol. 83:128-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowman, J. J., J. S. Orlando, D. J. Davido, A. S. Kushnir, and P. A. Schaffer. 2009. Transient expression of herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP22 represses viral promoter activity and complements the replication of an ICP22 null virus. J. Virol. 83:8733-8743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowman, J. J., and P. A. Schaffer. 2009. Origin of expression of the herpes simplex virus type 1 protein U(S)1.5. J. Virol. 83:9183-9194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durand, L. O., and B. Roizman. 2008. Role of cdk9 in the optimization of expression of the genes regulated by ICP22 of herpes simplex virus 1. J. Virol. 82:10591-10599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eide, T., et al. 1998. Identification of the UL4 protein of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Gen. Virol. 79(Pt. 12):3033-3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser, K. A., and S. A. Rice. 2007. Herpes simplex virus immediate-early protein ICP22 triggers loss of serine 2-phosphorylated RNA polymerase II. J. Virol. 81:5091-5101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu, C. D., Y. Chinenov, and T. K. Kerppola. 2002. Visualization of interactions among bZIP and Rel family proteins in living cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Mol. Cell 9:789-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jahedi, S., N. S. Markovitz, F. Filatov, and B. Roizman. 1999. Colocalization of the herpes simplex virus 1 UL4 protein with infected cell protein 22 in small, dense nuclear structures formed prior to onset of DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 73:5132-5138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jun, P. Y., et al. 1998. The UL4 gene of herpes simplex virus type 1 is dispensable for latency, reactivation and pathogenesis in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 79(Pt. 7):1603-1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerppola, T. K. 2006. Design and implementation of bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays for the visualization of protein interactions in living cells. Nat. Protoc. 1:1278-1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leopardi, R., P. L. Ward, W. O. Ogle, and B. Roizman. 1997. Association of herpes simplex virus regulatory protein ICP22 with transcriptional complexes containing EAP, ICP4, RNA polymerase II, and viral DNA requires posttranslational modification by the U(L)13 proteinkinase. J. Virol. 71:1133-1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin, F., X. Ren, H. Guo, Q. Ding, and A. C. Zheng. 2010. Expression, purification of the UL3 protein of herpes simplex virus type 1, and production of UL3 polyclonal antibody. J. Virol. Methods 166:72-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long, M. C., V. Leong, P. A. Schaffer, C. A. Spencer, and S. A. Rice. 1999. ICP22 and the UL13 protein kinase are both required for herpes simplex virus-induced modification of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II. J. Virol. 73:5593-5604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markovitz, N. S., F. Filatov, and B. Roizman. 1999. The U(L)3 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 is translated predominantly from the second in-frame methionine codon and is subject to at least two posttranslational modifications. J. Virol. 73:8010-8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markovitz, N. S., and B. Roizman. 2000. Small dense nuclear bodies are the site of localization of herpes simplex virus 1 U(L)3 and U(L)4 proteins and of ICP22 only when the latter protein is present. J. Virol. 74:523-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orlando, J. S., et al. 2006. ICP22 is required for wild-type composition and infectivity of herpes simplex virus type 1 virions. J. Virol. 80:9381-9390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan, W., X. Ren, H. Guo, Q. Ding, and A. C. Zheng. 2010. Expression, purification of herpes simplex virus type 1 UL4 protein, and production and characterization of UL4 polyclonal antibody. J. Virol. Methods 163:465-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roizman, B. 1996. The function of herpes simplex virus genes: a primer for genetic engineering of novel vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:11307-11312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roizman, B., D. M. Knipe, and R. J. Whitley. 2007. Herpes simplex virus, p. 2501-2601. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 23.Shyu, Y. J., and C. D. Hu. 2008. Fluorescence complementation: an emerging tool for biological research. Trends Biotechnol. 26:622-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shyu, Y. J., C. D. Suarez, and C. D. Hu. 2008. Visualization of AP-1 NF-kappaB ternary complexes in living cells by using a BiFC-based FRET. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:151-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith-Donald, B. A., L. O. Durand, and B. Roizman. 2008. Role of cellular phosphatase cdc25C in herpes simplex virus 1 replication. J. Virol. 82:4527-4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith-Donald, B. A., and B. Roizman. 2008. The interaction of herpes simplex virus 1 regulatory protein ICP22 with the cdc25C phosphatase is enabled in vitro by viral protein kinases US3 and UL13. J. Virol. 82:4533-4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ward, P. L., B. Taddeo, N. S. Markovitz, and B. Roizman. 2000. Identification of a novel expressed open reading frame situated between genes U(L)20 and U(L)21 of the herpes simplex virus 1 genome. Virology 266:275-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]