Abstract

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is currently the leading cause of death worldwide and together with diabetes, poses a serious health threat, particularly in the Indian Asian population. Risk factor management has evolved considerably with the continued emergence of new and thought-provoking evidence. The stream of laboratory- and population-based research findings as well as unresolved controversies may pose dilemmas and conflicting impulses in most clinicians, and even in our more well-informed patients. As results of the most recent clinical trials on glycaemic control for macrovascular risk reduction are woven into concrete clinical practice guidelines, this paper seeks to sort through unwieldy evidence, keeping these findings in perspective, to deliver a clearer message for the context of South Asia and cardio-metabolic risk management.

Keywords: Coronary heart disease, diabetes, glycaemic control, hypertension, lipid, risk factors

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD), comprising coronary heart (CHD) and cerebro-vascular diseases, are currently the leading cause of death globally, accounting for 21.9 per cent of total deaths, and are projected to increase to 26.3 per cent by 20301. The factors that coalesce to increase the risk of developing atherosclerotic CHD were demonstrated in Framingham in the mid-20th century2 and have subsequently been shown to be pervasive across ethnicities and regions of the world3. These are not new risks, but the ubiquity of smoking, dyslipidaemia, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension has been gradually escalating4, and is thought to be the driving influence behind the epidemic of heart disease faced today.

Of the risk factors, diabetes, and its predominant form, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), has a distinctive association with CHD. Those with diabetes have two- to four-fold higher risk of developing coronary disease than people without diabetes5, and CVD accounts for an overwhelming 65-75 per cent of deaths in people with diabetes6,7. More significantly however, the age- and sex-adjusted mortality risk in diabetic patients without pre-existing coronary artery disease was found to be equal to that of non-diabetic individuals with prior myocardial infarction (MI)8. These remarkable findings regarding higher risk of mortality9–11 have led to suspicion that common precursors predispose to diabetes and CHD12,13, with subsequent implications that insulin resistance, visceral adiposity, and excess inflammation14–16 underlie the pathophysiology of thrombogenesis. In addition, a complex mix of mechanistic processes such as oxidative stress, enhanced atherogenecity of cholesterol particles, abnormal vascular reactivity, augmented haemostatic activation, and renal dysfunction have been proposed as features characteristic of T2DM that may confer excess risk of CHD17.

People of Indian Asian descent make up over a fifth of the world’s population, combining inhabitants of the subcontinent and the Indian diaspora living elsewhere. The so-called “Asian Indian Phenotype” refers to an amalgamation of clinical (larger waist-to-hip and waist-to-height ratios signalling excess visceral adiposity), biochemical (insulin resistance, lower adiponectin, and higher C-reactive protein levels) and metabolic abnormalities [raised triglycerides, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol] that are more prevalent in individuals of South Asian origin and predispose this group to developing diabetes and premature CHD18–20. It is expected that individuals of Indian Asian ethnicity will account for between 40-60 per cent of global CVD burden within the next 10-15 years21. The astonishingly higher risk in this particular ethnic group has been attributed to underlying genetic susceptibility22,23 unmasked by environmental factors (permeation of contemporary lifestyle practices)24 or intrauterine programming which predisposes to asymmetric energy metabolism and rapid, excess accumulation of visceral body fat in adult life25–27.

In terms of absolute numbers of individuals with diabetes, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh make up three of the top ten countries globally28 and together, the region with the highest number of diabetes-related deaths currently29. India alone is estimated to have 50.8 million inhabitants with diabetes, the most of any country worldwide29. Propelled by socio-economic transformation, population ageing, burgeoning levels of overweight30 and proliferation of individuals and children with pre-diabetes (impaired glucose regulation)31, increase in T2DM29,32,33 and CHD4 will result in even greater future burdens.

The proportion of coronary disease patients with diabetes varies across countries, but approximately one-fifth of clinical trial (18%)34 and registry patients (15.1-21.4%)35 are documented as known diabetes patients. India stands out as an anomaly with 30.4 per cent36 and 39.1 per cent35 of CHD patients reporting known diabetes in national and international prospective registries. These proportions may be deemed the result of high background prevalence of glucose abnormalities in India. However, given that South Asians have higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors37,38, higher prevalence of T2DM, and earlier onset of CHD despite a normal body mass index (BMI) by international standards18,37,39,40, the premise that this population is more susceptible to diabetes and CVD19,20, and that these conditions are interlinked, is plausible.

Though previously CHD and T2DM were considered mainly diseases of affluence, reversal of socio-economic gradient in these diseases is starting as lower socio-economic groups in South Asia are exhibiting ever-increasing risk41,42. In addition, characteristic disparities (rural-urban split, public-private health care and low awareness) that are pervasive across the region, combined with chronicity and asymptomatic nature (silent killer) of non-communicable risk factors and diseases, perpetuate delays in diagnosis, inertia to seek care, and effective self-management of risks.

Risk factor control in cardiovascular disease reduction

Broadly speaking, established CVD risk factors most often do not occur in isolation, and addition of associated morbidities results in multiplicative, rather than additive, amplification of risk10. Once any individual factor is identified, systematic, comprehensive, and regular assessments should be undertaken to identify the development of co-existing risks or target organ complications, and treatment plus monitoring should be diligently instituted43. Driven by physician eagerness, haste, and to some extent, pharmaceutical sector interests44,45 and persuasion46, there has been strong emphasis on medication usage in managing dyslipidaemia, hypertension, and diabetes. This has detracted somewhat from the significant benefits that can be gleaned from alteration in lifestyle (nutrition47, weight, physical activity and tobacco use48) that occurs upstream of metabolic disturbances.

There is robust evidence that lifestyle modification (regular, moderate physical activity and healthy dietary habits) has a sustained effect on reducing incidence of diabetes49–51, and helps reduce the occurrence and mortality of CVD events in people with and without established CHD52. Iestra and colleagues53 have shown relative risk of mortality is reduced in the general population that stop smoking (up to 50% reduction), engage in moderate physical activity (20-30%), and adopt a combination of healthy dietary habits (limited intake of saturated fats, regular fish consumption, sufficient fruit and vegetable intake, and limited salt consumption - together, 15-40% reduction).

Randomized clinical trials evaluating individual risk factor control with pharmaceutical agents in patients with diabetes have also demonstrated reduction in surrogate markers, which translated into lower incidence of cardiovascular events and mortality. These findings have been utilized to institute clinical practice guidelines and standards of care based on strength of evidence and cost-effectiveness of interventions Table I.

Table I.

Evidence-based cardiovascular risk management targets in diabetes

| Target risk factor | Class of recommendation & level of evidence | Recommended targets |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESC | ADA | |||

| Glycaemia | Glycosylated haemoglobin | Normoglycaemia reduces risk of microvascular complications (Level A, Class I) | < 6.5 % | ≤ 7.0 %; individualize based on patient profile |

| Fasting plasma glucose | Metformin = first line for overweight T2DM (Level C, Class IIb) | < 6.0 mmol (108 mg/dl) | 3.9–7.2 mmol/l (70–130 mg/dl) | |

| Post-prandial glucose | Early stepwise increases in therapy improves morbidity & mortality (Level B, Class IIa) | T2DM < 7.5 mmol (135mg/dl); T1DM 7.5-9.0 mmol (135-160 mg/dl) | 10.0 mmol/l (180 mg/dl) | |

| Lipids | Total cholesterol | Measure fasting lipid profile annually to every 2 yr (Level B/C, Class IIb) depending on risk | < 4.5 mmol (175 mg/dl); If TC>3.5 mmol, aim for 30-40% LDL↓ | |

| LDL-cholesterol | Add statin to lifestyle therapy where overt CVD or no CVD, but >40 yr of age with ≥1 risk factor (Level A, Class I); If LDL targets not met despite maximal drug dose, aim for 30-40% reduction from baseline (Level A) | ≤ 1.8 mmol (70 mg/dl) | <2.6 mmol/l (100 mg/dl); <1.8 mmol/l (70 mg/dl) if overt CVD | |

| HDL-cholesterol | ↑HDL & ↓Triglyc. desirable (Level C, Class IIb) | Men: >1.0 mmol (40 mg/dl) Women: >1.2 mmol (46 mg/dl) | Men: >1.0 mmol (40 mg/dl) Women: >1.3 mmol (50 mg/dl) | |

| Triglycerides | Combining statins with other lipid-altering agents may be considered (Level C, Class III) | <1.7 mmol (150 mg/dl) | <1.7 mmol (150 mg/dl) | |

| BP | BP control | BP targets & monitoring at every visit (level B-C) | <130/80 mmHg | <130/80 mmHg |

| (& use of RAS-modifying agent) | Pharmacologic therapy if >140/90 (Level A, Class I); multiple therapies often required for achieving targets (Level B) | <125/75 mmHg (if renal impairment) | ||

| Medication | Anti-platelet agents | Aspirin use in patients with history of CVD (Level A, Class I); if male >50 yr or female >60 yr with 1 additional risk factor (Level C) | ASA 75 mg/day | ASA 75-162 mg/day |

| Clopidogrel (Level C, Class IIa) if severe CVD; combine with aspirin in 1st yr after MI (Level B) | ||||

| ACE-inhibitor use | Where additional risk factors exist: To delay renal complications (Class I, Level A) | |||

| To reduce CV events (Level B) | ||||

| Vaccinations | Annual influenza – Level C One lifetime pneumococcal vaccine (for >65 yr, renal disease/post-transplant patients) – Level C | |||

| Lifestyle | Smoking | Advise cessation (Level A) Utilize counselling & therapies (Level B) | Cessation | Cessation |

| Regular physical activity | Level A, Class I | 30-45 min/day | 150 min/wk of moderate intensity aerobic activity (+/- resistance training 3 times/wk) | |

| Weight control | Either low-carbohydrate or low-fat calorierestricted diet may be effective (up to 1 yr)-Level of evidence A | BMI<25.0 kg/m2* 10 % weight reduction (if already overweight) | Especially in overweight or obese individuals with insulin resistance | |

| Assimilated from Task Force on DM & CVD (ESC, European Society of Cardiology and European Association for Study of Diabetes, 2007)83 & American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes - 201084 | ||||

Values for glucose & lipids presented as mmol/l (mg/dl)

Lower BMI targets applicable to Indian Asian and Chinese Asian populations; RAS, renin-angiotensin system; ACE-inhibitor, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin)

-

Level of evidence A:Data derived from multiple, well-conducted, adequately powered randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses

-

Level of evidence B:Data derived from a single randomized clinical trial or large non-randomized studies (cohort, registries, meta-analysis of cohort studies)

-

Level of evidence C:Consensus of opinion of experts and/or small studies, retrospective or observational studies (+/- methodological flaws, biases)

Classes of Recommendation

-

Class I:Evidence &/or general agreement that a given diagnostic procedure/treatment is beneficial, useful, and effective

-

Class II:Conflicting evidence and/or a divergence of opinion about the usefulness/efficacy of the treatment or procedure

-

Class IIa:Weight of evidence/opinion is in favour of usefulness/efficacy

-

Class IIb:Usefulness/efficacy is less well established by evidence/opinion

-

Class III:Evidence or general agreement that the treatment or procedure is not useful/effective and in some cases may be harmful

Dyslipidaemia is a significant predictor of CVD events and mortality in diabetes patients55,56. Attentive management of low-density lipoprotein (LDL-), high-density lipoprotein (HDL-) and total cholesterol, but also triglyceride subfractions, is vital. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) in particular, have indisputable proven efficacy, demonstrating 27-40 per cent reductions in LDL-cholesterol in all placebo-controlled trials (Table II), and subsequent decreases in occurrence of cardiovascular events and mortality by 25 to 42 per cent57,58 in persons with and without diabetes or previous acute coronary syndrome (ACS). This benefit extends to those with already controlled LDL-cholesterol fractions59.

Table II.

Intermediate and end point effect size estimates for drug-based interventions

| Trial (DM sample size) | Patient characteristics | Intervention | Intermediate outcome | CVD risk reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDL lowering | ||||

| HPS-DM (5,963)57 | DM without CHD | Simvastatin 40 mg | 31%↓ in LDL | 22-26%↓ composite end points |

| CARDS (2,838)58 | T2DMwith≥ 1 RF | Atorvastatin 10 mg | 40%↓ in LDL | 37%↓ in events, 27%↓ CV mortality |

| 4S-DM (483, IFG=678)85 | DM subgroup & IFG | Simvastatin 20-40 mg | 36%↓ in LDL | 42%↓ in CHD events, 28%↓ CV mortality |

| CARE-DM(586)86 | DM subgroup | Pravastatin 40 mg | 27% ↓ in LDL | 25%↓ in events, 32%↓ revascularization |

| HDL & Triglycerides | ||||

| VA-HIT (2,531)60 | CHD with normal LDL | Gemfibrozil | 6%↑HDL; 31%↓Tg | 24%↓ in CV events, 32%↓ composite |

| FIELD (9,795)62 | T2DM, age 50-75, ↑chol | Fenofibrate 200 mg | 7%↓TC; 22%↓Tg | 24%↓ in non-fatal MI, 11%↓ CV events |

| BP Control | ||||

| HDS-UKPDS(1,148)69 | DM subjects | Aggressive BP Rx | ↓BP (144/82) | 32%↓ in DM-related deaths |

| HOT-DM (1,501)70 | DM subjects | dBP≤80 vs ≤90mmHg | ↓dBP 20.3-24.3 | 51%↓ in CV end points |

| ADVANCE-BP71 | T2DMwith≥1 RF/TOD | Add ACEi / Indap. | ↓sBP 5.6, ↓dBP2.2 | 8%↓ in CVD events, 18%↓ CV mortality |

| ABCD (950)87 | T2DM | dBP≤75 vs ≤90mmHg | 128/75 vs. 137/81 | BP↓ stabilized Cr Cl & ↓ micro vase. TOD |

| ABCD (470)88 | T2DM with HTN | ACEi vs CCB | Similar BP ↓ | ACEi 9.5 times ↓ composite outcomes |

| Syst-EUR (492)72 | Systolic HTN & DM | CCB ± ACE/Thi | ↓sBP8.6, ↓dBP3.9 | 63%↓ in CV events |

| ALLHAT-DM(13,101)74 | DM, IFG (1,399) | ACEi / CCB / thiazide | ↓sBP: Thi>CCB>ACE | No difference in CV events; thiaz ↑ FBG |

| BPLTTC-DM (33,395)89 | DM patients from BP trials | meta-analysis:27 trials | Similar efficacy of drug regimens | Comparable ↓ in CV events in DM/non; limited evidence for lower BP target in DM |

| HAS (ACE/ARB)modifier | ||||

| RENAAL(1,513)78 | T2DM with nephropathy | Losartan (ARB) | ↓BP | 16-28%↓ (or 2 yr) delay in dialysis/Tx |

| HOPE (3,577)80 | DM with ≥ 1 RF | Ramipril (ACEi) | Adjusted for Δ in BP | 25%↓ in composite endpoint |

| ABCD-2 (129)77 | T2DM & normotensive | Valsartan (ARB) | 118/75 vs. 124/80 | ↓ in urinary albumin & possibly CVD91 |

| Anti-platelet therapy | ||||

| ATC (4,500)91 | Meta-analysis (high-risk) | Aspirin | 18%↓ incidence of CV events | |

| HOT-DM (1,501)71 | DM subjects | Aspirin | 15%↓ in events, 36%↓ in mortality | |

| CAPRIE (3,866)92,93 | DM subjects | Clopidogrel vs ASA | 9-12% less events in Clopidogrel arm |

*Composite outcomes most often include: non-fatal MI, stroke, revascularization &/or cardiovascular mortality

CV, cardiovascular; RF, risk factor; HTN, hypertension; Cr Cl, creatinine clearance; TOD, target organ damage; Tx, transplant; Δ, change; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin); ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; Indap., indapamide; ↓, decrease; ↑, increase; sBP, systolic BP; dBP, diastolic BP HPS, Heart Protection Study; CARDS, Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study; 4S, Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study; CARE, Cholesterol and Recurrent Events study; VA-HIT, Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention Trial; FIELD, Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes; HDS-UKPDS, Hypertension in Diabetes Study - United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study; HOT, Hypertension Optimal Treatment study; ADVANCE-BP, Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation trial, BP-lowering arm; ABCD, Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in Diabetes; SystEUR, Systolic Hypertension in Europe trial; BPLTTC, Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration; ALLHAT, Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial; HOPE, Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation; RENAAL, Reduction of Endpoints in NIDDM with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan; ABCD2-Valsartan, Appropriate Blood Pressure Control In Hypertensive and Normotensive Type 2 DM - Valsartan; ATC, Antiplatelet Trialists Collaboration; CAPRIE, Clopidogrel versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischaemic Events

There is ambiguity concerning the role of gemfibrozil, nicotinic acid, and fibrates in CVD risk reduction. At least modest improvements in HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides have been postulated, but significant concrete translation into lower composites of CVD have not been exhibited in studies60–63. Since the evidence in favour of lowering LDL is so overwhelming59 and similar findings are awaited for triglyceride management and elevating HDL64,65, the primary emphasis of lipid management tends to focus on LDL. Dietary modification66 and addition of statins are, therefore, recommended as first-line management guidelines for lipid control in diagnosed diabetes patients or those with confirmed CVD.

Hypertension co-exists in a significant proportion of people with diabetes67. Lowering blood pressure (BP) produces dramatic benefits in these subjects and BP targets have been modified specifically to avert disabling and fatal complications in the form of nephropathy, retinopathy, and vascular events68. Several large randomized trials, sub-studies69–74, and meta-analyses75,76 which include patients with diabetes have shown benefit in reducing non-fatal myocardial infarction, chronic kidney disease77,78, and remarkable reductions in cardiovascular (51%)70 and all-cause mortality. The use of renin-angiotensin system (RAS) modifying agents [angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARB)] provide ancillary benefits in forestalling renal complications78 on top of BP control, and have additionally demonstrated lower composite CVD outcomes in numerous randomized trials, even after adjustment for changes in BP79–81. These cardio- and reno-protective effects (anti-atherosclerotic, reducing arterial stiffness, and improving endothelial function)73,82 are motivating more extensive application of RAS-modifier agents in patients with diabetes.

Previous evidence has also demonstrated the efficacy of low-dose daily aspirin use in preventing CVD events, especially as secondary prevention in those that have already suffered previous events94,95. However, a recent large meta-analysis96 cautions that ubiquitous use of low-dose aspirin for primary prevention may only be justified where net benefits of preventing coronary events in high-risk patients outweigh the increased risk of gastrointestinal and extra-cranial bleeds. As such, this study showed no significant effects on preventing first onset of stroke. The addition of clopidogrel is currently also recommended only for prevention of recurrent events92,93.

Glycaemic Control in Cardiovascular Risk Reduction: An Actively Evolving Paradigm

In patients with diabetes, where excess CVD risk has already been demonstrated, the relationship between glycaemia itself and CVD should not, theoretically, be in doubt. Even studies in non-diabetic subjects97,98, including a meta-regression analysis combining data from >95000 participants99, have shown an association between fasting blood glucose and CVD. Another meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies100 examined glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c a more stable, accurate, less error-prone measure of long-term glycaemic levels) and CVD in persons with diabetes and found 18 per cent (pooled RR 1.18; 95% CI 1.10 to 1.26) and 15 per cent (pooled RR 1.15; 95% CI 0.92 to 1.43) greater relative risk per 1 per cent increase in HbA1c in T2DM and T1DM, respectively. However, the converse of this association, whether reducing glucose levels to near-normal targets results in lower CVD events, is still a controversial topic.

Despite impressive reduction in microvascular complications69,101–103 and retrospective cohort data showing lower risk of strokes (21%) and MI (23%)104 with lower levels of glycaemia, the early prospective trial data evaluating macrovascular outcomes classically provided equivocal results [e.g. 16% (P=0.052) non-significant reduction in MI in United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)], citing reasons of inadequate power, follow-up101,102 or design deficiencies. More recent multi-centre trials sought to conclusively evaluate the influence of achieving lower therapeutic targets for glycaemic control on the incidence of CVD endpoints. Since a variety of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments are established, cost-effective, and safe interventions for glycaemic control106,107, the more contemporary theme of what level of glycaemia to achieve holds topical interest, requiring more in-depth discussion.

Three large prospective randomized trials attempted to definitively address the glycaemia and CVD debate. The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD)108, Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE)109, and Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial (VADT)110 studies randomized 10251, 11140, and 1791 T2DM patients, respectively, with co-existing risk factors and/or history of diabetic complications (including previous CVD events) into intensive (aiming for bold “near-normal” glycaemic targets) or conventional therapy groups, using different treatment regimens. After a 1.1 per cent relative difference in median HbA1c between the groups (6.4 vs. 7.5%) and 3.5 years of follow-up, ACCORD was prematurely discontinued due to 54 excess deaths in the intensive therapy arm. The ADVANCE trial achieved a 0.8 per cent lower median HbA1c (6.5%) in the intensive therapy arm compared to the standard group over a 5 year follow-up period and demonstrated a 10 per cent reduction in composite of major micro- and macro-vascular events (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.98; P=0.01), which did not remain significant after adjustment for reduction in nephropathy (21% reduction in intensive therapy group; HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.93; P=0.006). From a baseline median HbA1c level of 9.4 per cent, the VADT achieved A1c levels of 6.9 and 8.4 per cent in the intensive and standard groups, respectively109. However, there was no significant between-group difference in the composite primary outcome (HR 0.88; 95% CI, 0.75 to1.05; P=0.14), nor in the number of new, or progression of, microvascular complications. Across these three studies, the intensive therapy arms all reported higher incidence of hypoglycaemia requiring medical assistance and weight gain among participants.

Despite seemingly negative results, there are several points from these study results that should be kept in perspective, especially as outcomes of ongoing trials will continue to emerge at regular intervals in the future (Table III)111. Firstly, diabetes is still the leading cause of adult-onset blindness, end-stage renal disease, and non-traumatic lower-extremity amputations worldwide32,112,113, and glycaemic control overwhelmingly reduces these microvascular complications69,101,102. Therefore, blood glucose management remains a vital component of preventing disabling and fatal target organ damage in both T1DM and T2DM. Secondly, optimal glycaemic targets have been chosen based on this evidence from microvascular risk reduction and should at least be deemed appropriate considering the increased risks of hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and hyperhomocysteinaemia - themselves strong risks for CVD - which are associated with renal insufficiency. However, in the broader context of CVD prevention and considering the severity of chronic kidney disease, these targets may need to be customized according to individual risk114.

Table III.

Summary of trials assessing glycaemic control targets & alternative therapies

| Trial (sample size) | Patient characteristics | Intervention (F/up) | Results | CVD risk changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluating glycaemic target | ||||

| VADT (1,791)110 | DM & > 40 yr of age | Sequential therapy intensification vs. standard care PLUS education & management of RFs to both groups (6.25 yr) | Baseline: mean age 60, 40% previous events, most ≥ 1 RF Mean HbA1c (6.9 vs. 8.4%) | No significant difference in CVS events (235 vs 264, NS), microvascular complications or death between intensive & standard groups; Baseline coronary calcium was strongest predictor of CVD outcomes |

| ACCORD (10,251)108 | T2DM with previous CVD or ≥ 2 RF or albuminuria, atherosclerosis or LVH | Intensive glycaemic control (HbA1c ≤ 6) vs. standard therapy (A1c 7.0-7.9) -(discontinued after 3.5 yr) | Baseline: mean age 62, 35% prev. CVD; Median HbA1c Δ 1.1% (6.4 vs. 7.5%) | 20%↑ in death of any cause (including CVD / CHF / fatal procedures) |

| ADVANCE (11,140)109 | T2DM & history of complications or co-existing RF (200 centers) | Intensive glycaemic control (HbA1c ≤ 6.5) with gliclazide MR vs. conventional therapy (median 5 yr) | Baseline: mean age 66, 32% prev.CVD & 10% prev. microvascular TOD; Median HbA1c Δ 0.8% (6.5 vs. 7.3%) | 10%↓ composite of micro- & macro-vascular outcomes (NS after adjustment for 21%↓ in nephropathy) |

| Ray & colleagues Meta-analysis (33,040)117 | 5 trials – random effects meta-analysis | Intensive glycaemic control versus standard control; 163,000 person yr of follow up | Mean 0.9% lower A1c in intensive arms | 17% ↓ non-fatal MI 15% ↓ in CHD events No difference in stroke (HR 0.93; 0.81-1.06) and all-cause mortality (HR 1.02; 0.87-1.19) |

| CONTROL Meta-analysis (27,049)118 | 4 prospective trials including T2DM pts; mean age=62yr; median duration of DM=9 yr; | Intensive versus less-intensive glucose control over 4.4 yr | Mean 0.88% lower A1c in intensive arms | 9% ↓ in CVD events (as high as 16% benefit in those without pre-existing macrovascular disease) No difference in all-cause mortality (HR 1.04) and CVD-mortality (HR 1.10) |

| Trials evaluating alternative therapies | ||||

| ORIGIN (~10,000) | IFG, IGT, DM with CVD risk factors | Omega fatty-acid consumption | Do unsaturated fats have cardio-protective properties in patients with dysglycaemia? | |

| LookAHEAD (~5,000) | T2DM aged 45-74 with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 4 yr intensive weight-loss (11.5 yr planned f/up) | Only 10.1% achieved targets – sociodemographic & compliance factors | Powered for 90% probability of detecting 18% Δ in major CVD events |

| ASCEND (~10,000)127 | DM | Omega-3 fatty acids & Aspirin 100 mg/day (2×2 design) | Are Omega-3 FA & Aspirin of benefit independently & together in DM patients? | |

| SEARCH (9,000) | Youths (<20 yr) with DM (T1DM) | Cohort | Document prevalence of T1DM & follow service utilization, quality of care & development of complications | |

| HPS2-THRIVE (20,000)128 | Previous CVD (China, UK, Scandinavia); DM sub-population 7,500 | Niacin & MK-0524A | Does increasing HDL lower CVD event rate? | |

Source: Refs 111,114,129, and individual trail information websites: (http://www.searchfordiabetes.org/; http://www.lookaheadtrial.org/; http://www.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/ascend/; http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00069784; http://www.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/projects/hps2-thrive)

DM, diabetes mellitus; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; f/up, follow up; yr, year; Δ, change/difference; CHF, congestive heart failure; Omega-3 FA, omega-3 fatty acids; Gliclazide MR, modified-release preparation; UK, United Kingdom; RF, risk factor; TOD, target organ damage; NS, non-significant; prev, previous; VADT, Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial; ACCORD, Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes study; ADVANCE, Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation trial; CONTROL, Collaborators on Trials of Lowering Glucose; ORIGIN, Outcome Reduction with Initial Glargine Intervention trial; LookAHEAD, Action for Health in Diabetes study; ASCEND, A Study of Cardiovascular Events iN Diabetes; SEARCH, SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study; HPS2-THRIVE, Heart Protection Study 2 - Treatment of HDL to Reduce the Incidence of Vascular Events study

Other important considerations include the fact that participants in these large trials were high-risk patients with poor baseline control, high pre-existing use of insulin (among 35-50% of subjects), and a third (32-40%) already had pre-existing heart disease. Indeed, the average duration of diabetes (8.5-11 yr) must also weigh in as a factor, which motivates the assertion that either earlier17, or more sustained intervention is required to reduce the risk of prolonged metabolic disturbance. This was confirmed in the 17 yr follow-up of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)115 where the intensively treated type 1 diabetes patients had 42 and 57 per cent lower risk of CVD events and death from CVD, respectively, despite no difference found at earlier follow-up. The UKPDS ten-year follow-up116 also demonstrated delayed beneficial effects of early initiation of glycaemic control on macrovascular outcomes, a “metabolic memory” of sorts.

In addition to greater frequency of hypoglycaemia and weight gain in the intensive group participants, it has been postulated that serious adverse events and mortality may be attributable to more aggressive and rapid (e.g., ACCORD and VADT permitted any drug combination with rapid glucose-lowering) than measured (e.g., ADVANCE used sulphonylureas with gradual between-group differences in glycaemia) glucose-lowering; however, there are currently no data to support this assertion.

Recently published meta-analyses117,118 (Table III) have sought to examine the data in its entirety, pooling data and performing several pre-specified sub-analyses. The findings seem to conclude that intensive glucose lowering may have significant benefits in preventing coronary events, especially in those without pre-existing established atherosclerotic vascular disease; however, there is seemingly no mortality-reducing benefit from targeted glucose management. Based on the totality of evidence available, the American Diabetes Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Heart Association jointly issued recommendations119 to assuage uncertainty and confusion that emerged among clinicians and scientists following the release of these trial results. Broadly, current guidelines support customizing the intensity of glucose management depending on individual patient characteristics and co-morbidities.

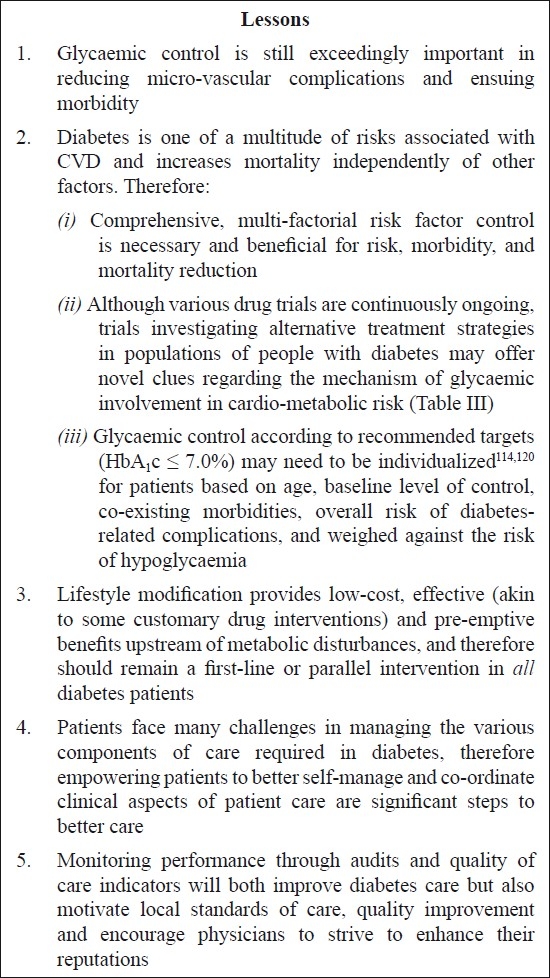

A final and very convincing point is that glycaemia is not the sole consideration in CVD risk, but rather plays a role in the confluence of multi-factorial influences120. Therefore, exclusively concentrating on glucose control may be a key limitation of these focused randomized trials. A meta-analysis which presented a substantial 27 per cent greater risk for CVD between the highest (8.3-10.8 mmol/l) and lowest (3.8-5.9 mmol/l) post-challenge blood glucose levels, subsequently also revealed significant attenuation of risk (to 19%) when adjustment was made for co-existing CVD risk factors121. Progression of carotid atherosclerosis in diabetes patients showed analogous attenuation upon controlling for other CVD risks122. By aggressively managing all modifiable risk factors (blood pressure and lipid control)57,58,123 and implementing evidence-based guidelines94,124 vascular events and mortality can be reduced considerably125,126. Also, within these large trials of glycemic control, embedded trials were conducted to examine the effect of targeted, rigorous treatment of co-morbid risk factors on event rates; results from these trials are eagerly anticipated. A good example of comprehensive risk factor control is the Steno-II study investigated integrated, comprehensive, intensified risk factor control in a randomized fashion in Danish T2DM patients with microalbuminuria. They demonstrated declines in metabolic parameters (including HbA1c values) which translated into sizeable gains in prevention of CVD (53%) over 7.8 yr125 and lower mortality from cardiovascular events (59%) over 13.3 yr of follow-up126. The case for concerted multiple risk factor modification and drawing well-informed lessons Fig. from the literature is therefore compelling16,67,114,125.

Fig.

Themes and lessons emerging from recent trial evidence

Interpretation of findings is influenced by qualitative and quantitative heterogeneity across trials and publication biases noted in most meta-analyses. It should also be noted that some studies compare 10-year risk scores, others measure actual events and mortality, and the differences are mainly a function of duration of follow up. Other noteworthy dissimilarities in studies evaluated are in characteristics of patients enrolled, particularly demographic characteristics, socio-economic status, baseline level of control and risk factor duration prior to participation in the study, as well as enduring motivation of participants. There is also a crucial distinction between reporting relative reductions of biochemical parameters versus standard therapy as in some studies, and actually achieving recommended optimal targets in others.

Conclusions

Glycaemic and CVD risk factors control can be challenging in any context, not least in the sub-continent. Evidence-based recommendations for diabetes care, mainly based on trials in Anglo-Caucasian populations, are available, but there is no indication of how well these guidelines are implemented in South Asia, nor any randomized trial evidence is available from this particular population group. The Delhi Diabetes Community (DEDICOM)130 and DiabCare Asia131 surveys suggest that quality of diabetes care is sub-optimal (participants reported low frequency of self-monitoring and poor glycaemic control (HbA1c >8%) amongst 42-50 per cent of diabetes patients, only 17.5 per cent were taking aspirin while lipid and BP targets were not met in almost half the subjects surveyed) in a region where dedicated, diligent follow up of diabetes patients should be a priority, given the amplified risks. Poor clinical practices such as these132 help explain the remarkable proportion (54%) that reported severe late-stage complications. Focused, context-specific research133 and careful analyses that integrate medication therapy and preventative lifestyle choices may pave the way for alignment of resources with needs, health systems development, and consequent reductions in morbidity and mortality.

References

- 1.Department of Measurement & Health Information Systems of the Information, Evidence and Research Cluster. Geneva: WHO Press; 2008. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics; pp. 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannel WB. Some lessons in cardiovascular epidemiology from Framingham. Am J Cardiol. 1976;37:269–82. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta R, Joshi P, Mohan V, Reddy KS, Yusuf S. Epidemiology and causation of coronary heart disease and stroke in India. Heart. 2008;94:16–26. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.132951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham study. JAMA. 1979;241:2035–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.241.19.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BE. Cause-specific mortality in a population-based study of diabetes. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:1158–62. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.9.1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geiss LS, Herman WM, Smith PJ. Diabetes in America. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: NIH & NIDDK: National Diabetes Information Clearing house; 1995. Mortality in non-insulin-dependent diabetes; pp. 233–55. In: National Diabetes Data Group, editor. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:229–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donahoe SM, Stewart GC, McCabe CH, Mohanavelu S, Murphy SA, Cannon CP, et al. Diabetes and mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2007;298:765–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.7.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton JD, Wentworth D. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:434–44. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.2.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franco OH, Steyerberg EW, Hu FB, Mackenbach J, Nusselder W. Associations of diabetes mellitus wth total life expectancy and life expectancy with and without cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1145–51. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laakso M, Kuusisto J. Epidemiological evidence for the association of hyperglycaemia and atherosclerotic vascular disease in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Ann Med. 1996;28:415–8. doi: 10.3109/07853899608999101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haffner SM. Epidemiology of insulin resistance and its relation to coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:11J–14J. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plutzky J, Viberti G, Haffner S. Atherosclerosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance: mechanistic links and therapeutic targets. J Diabetes Complications. 2002;16:401–15. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(02)00202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haffner SM. Abdominal adiposity and cardiometabolic risk: do we have all the answers? Am J Med. 2007;120(9 Suppl 1):S10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnett AH. The importance of treating cardiometabolic risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2008;5:9–14. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2008.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deedwania PC, Fonseca VA. Diabetes, prediabetes, and cardiovascular risk: shifting the paradigm. Am J Med. 2005;118:939–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohan V, Sandeep S, Deepa R, Shah B, Varghese C. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes: Indian scenario. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:217–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKeigue PM, Ferrie JE, Pierpoint T, Marmot MG. Association of early-onset coronary heart disease in South Asian men with glucose intolerance and hyperinsulinemia. Circulation. 1993;87:152–61. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enas EA, Mehta J. Malignant coronary artery disease in young Asian Indians: thoughts on pathogenesis, prevention, and therapy. Coronary Artery Disease in Asian Indians (CADI) Study. Clin Cardiol. 1995;18:131–5. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960180305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaziano TA, Reddy KS, Paccaud F, Horton S, Chaturvedi V. Cardiovascular Disease. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, et al., editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 645–62. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radha V, Mohan V. Genetic predisposition to type 2 diabetes among Asian Indians. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:259–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chambers JC, Elliott P, Zabaneh D, Zhang W, Li Y, Froguel P, et al. Common genetic variation near MC4R is associated with waist circumference and insulin resistance. Nat Genet. 2008;40:716–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta M, Brister S. Is South Asian ethnicity an independent cardiovascular risk factor? Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:193–7. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70895-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yajnik CS. Early life origins of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in India and other Asian countries. J Nutr. 2004;134:205–10. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramachandran A. Epidemiology of diabetes in India - three decades of research. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:34–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lev-Ran A. Human obesity: an evolutionary approach to understanding our bulging waistline. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2001;17:347–62. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diabetes atlas. 4th ed. 2009. International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Available at: www.diabetesatlas.org. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta R, Misra A, Pais P, Rastogi P, Gupta VP. Correlation of regional cardiovascular disease mortality in India with lifestyle and nutritional factors. Int J Cardiol. 2006;108:291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohan V, Jaydip R, Deepa R. Type 2 diabetes in Asian Indian youth. Pediatr Diabetes. 2007;8(Suppl 9):28–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The silent epidemic: An economic study of diabetes in developed and developing countries. New York, London, Hong Kong: 2007. Economic Intelligence Unit. The Economist, June. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta R, Kumar P. Global diabetes landscape - Type 2 diabetes mellitus in south Asia: Epidemiology, risk factors, and control. Insulin. 2008;3:78–94. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGuire DK, Emanuelsson H, Granger CB, Magnus Ohmn E, Moliterno DJ, White HD, et al. Influence of diabetes mellitus on clinical outcomes across the spectrum of acute coronary syndromes. Findings from the GUSTO-IIb study. GUSTO IIb Investigators. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1750–8. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prabhakaran D, Yusuf S, Mehta S, Pogue J, Avezum A, Budaj A, et al. Two-year outcomes in patients admitted with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome: results of the OASIS registry 1 and 2. Indian Heart J. 2005;57:217–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xavier D, Pais P, Devereaux PJ, Xie C, Prabhakaran D, Reddy KS, et al. Treatment and outcomes of acute coronary syndromes in India (CREATE): a prospective analysis of registry data. Lancet. 2008;371:1435–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60623-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joshi P, Islam S, Pais P, Reddy S, Dorairaj P, Kazmi K, et al. Risk factors for early myocardial infarction in South Asians compared with individuals in other countries. JAMA. 2007;297:286–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Latha E, Satyavani K, Vijay V. Clustering of cardiovascular risk factors in urban Asian Indians. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:967–71. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.6.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diaz VA, Mainous AG, 3rd, Baker R, Carnemolla M, Majeed A. How does ethnicity affect the association between obesity and diabetes? Diabet Med. 2007;24:1199–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghaffar A, Reddy KS, Singhi M. Burden of non-communicable diseases in South Asia. BMJ. 2004;328:807–10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Misra A, Pandey RM, Devi JR, Sharma R, Vikram NK, Khanna N. High prevalence of diabetes, obesity and dyslipidaemia in urban slum population in northern India. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1722–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta R, Gupta VP, Sarna M, Prakash H, Rastogi S, Gupta KD. Serial epidemiological surveys in an urban Indian population demonstrate increasing coronary risk factors among the lower socioeconomic strata. J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:470–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vijan S, Stevens DL, Herman WH, Funnell MM, Standiford CJ. Screening, prevention, counseling, and treatment for the complications of type II diabetes mellitus putting evidence into practice. J Gen Int Med. 1997;12:567–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herper M, Kang P. Forbes Inc.: Pharmaceuticals. The world’s ten best-selling drugs. Forbes Inc. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/2006/03/21/pfizer-merck-amgen-cx_mh_pk_0321topdrugs.html accessed on June 24, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang TJ, Ausiello JC, Stafford RS. Trends in antihypertensive drug advertising, 1985-1996. Circulation. 1999;99:2055–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.15.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Avorn J. Torcetrapib and atorvastatin--should marketing drive the research agenda? N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2573–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kris-Etherton P, Eckel RH, Howard BV, St, Jeor S, Bazzarre TL. Lyon Diet Heart Study : Benefits of a Mediterranean-Style, National Cholesterol Education Program/American Heart Association Step I Dietary Pattern on Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2001;103:1823–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Critchley JA, Capewell S. Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: A systematic review. JAMA. 2003;290:86–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Christophi CA, Hoffman HJ, Brenneman AT, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009;374:1677–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, Gregg EW, Yang W, Gong Q, et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371:1783–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60766-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lindstrom J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, Aunola S, Eriksson JG, Hemio K, et al. Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet. 2006;368:1673–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mozaffarian D, Wilson PWF, Kannel WB. Beyond established and novel risk factors: Lifestyle risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;117:3031–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.738732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iestra JA, Kromhout D, van der Schouw YT, Grobbee DE, Boshuizen HC, van Staveren WA. Effect size estimates of lifestyle and dietary changes on all-cause mortality in coronary artery disease patients: a systematic review. Circulation. 2005;112:924–34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.503995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980-2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Laakso M. Dyslipidemia, morbidity, and mortality in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Lipoproteins and coronary heart disease in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 1997;11:137–41. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(96)00092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Haffner SM, Pyorala K, Kallio V, Laakso M. Dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia predict coronary heart disease events in middle-aged patients with NIDDM. Diabetes. 1997;46:1354–9. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.8.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Collins R, Armitage J, Parish S, Sleigh P, Peto R. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin in 5963 people with diabetes: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:2005–16. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13636-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, Hitman GA, Neil HA, Livingstone SJ, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:685–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16895-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rubins HB, Robins SJ, Collins D, Fye CL, Anderson JW, Elam MB, et al. Gemfibrozil for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in men with low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Intervention Trial Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:410–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908053410604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frick MH, Elo O, Haapa K, Heinonen OP, Heinsalmi P, Helo P, et al. Helsinki Heart Study: primary-prevention trial with gemfibrozil in middle-aged men with dyslipidemia. Safety of treatment, changes in risk factors, and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1237–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711123172001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Keech A, Simes RJ, Barter P, Best J, Scott R, Taskinen MR, et al. Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1849–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67667-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Canner PL, Berge KG, Wenger NK, Stamler J, Friedman L, Prineas RJ, et al. Fifteen year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245–55. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singh IM, Shishehbor MH, Ansell BJ. High-density lipoprotein as a therapeutic target: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:786–98. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.7.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ginsberg HN, Bonds DE, Lovato LC, Crouse JR, Elam MB, Linz PE, et al. Evolution of the Lipid Trial Protocol of the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) Trial. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99(Suppl 1):S56–S67. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Manley SE, Stratton IM, Cull CA, Frighi V, Eeley EA, Matthews DR, et al. Effects of three months’ diet after diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes on plasma lipids and lipoproteins (UKPDS 45). UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Diabet Med. 2000;17:518–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kempler P. Learning from large cardiovascular clinical trials: classical cardiovascular risk factors. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;68(Suppl 1):S43–7. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Adler AI, Stratton IM, Neil HA, Yudkin JS, Matthews DR, Cull CA, et al. Association of systolic blood pressure with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 36): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321:412–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. BMJ. 1998;317:703–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlof B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet. 1998;351:1755–62. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Woodward M, Billot L, et al. Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:829–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tuomilehto J, Rastenyte D, Birkenhager WH, Thijs L, Antikainenn R, Bulpitt CJ, et al. Effects of calcium-channel blockade in older patients with diabetes and systolic hypertension. Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:677–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cockcroft JR. ACE inhibition in hypertension: focus on perindopril. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2007;7:303–17. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200707050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Whelton PK, Barzilay J, Cushman WC, Davis BR, Iiamathi E, Kostis JB, et al. Clinical outcomes in antihypertensive treatment of type 2 diabetes, impaired fasting glucose concentration, and normoglycemia: antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT) Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1401–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Collins R, Peto R, MacMahon S, Hebert P, Fiebach NH, Eberlein KA, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 2, Short-term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet. 1990;335:827–38. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90944-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Turnbull F, Neal B, Algert C, Chalmers J, Chapman N, Cutler J, et al. Effects of different blood pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events in individuals with and without diabetes mellitus: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1410–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Estacio RO, Coll JR, Tran ZV, Schrier RW. Effect of intensive blood pressure control with valsartan on urinary albumin excretion in normotensive patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:1241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pahor M, Psaty BM, Alderman MH, Applegate WB, Williamson JD, Furberg CD. Therapeutic benefits of ACE inhibitors and other antihypertensive drugs in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:888–92. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. Lancet. 2000;355:253–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chalmers J, Joshi R, Patel A. Advances in reducing the burden of vascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:434–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.04892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vijayaraghavan K, Deedwania PC. The renin angiotensin system as a therapeutic target to prevent diabetes and its complications. Cardiol Clin. 2005;23:165–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Authors/Task Force Members, Ryden L, Standl E, Bartnik M, Van den Berghe G, Betteridge J, et al. Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases: executive summary: The Task Force on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Eur Heart J. 2007;28:88–136. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Suppl 1):S11–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haffner SM, Alexander CM, Cook TJ, Boccuzzi SJ, Musliner TA, Pedersen TR, et al. Reduced coronary events in simvastatin-treated patients with coronary heart disease and diabetes or impaired fasting glucose levels: subgroup analyses in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2661–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.22.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Goldberg RB, Mellies MJ, Sacks FM, Moye LA, Howard BV, Howard WJ, et al. Cardiovascular events and their reduction with pravastatin in diabetic and glucose-intolerant myocardial infarction survivors with average cholesterol levels: subgroup analyses in the cholesterol and recurrent events (CARE) trial. The Care Investigators. Circulation. 1998;98:2513–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.23.2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Estacio RO, Schrier RW. Antihypertensive therapy in type 2 diabetes: implications of the appropriate blood pressure control in diabetes (ABCD) trial. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:9R–14R. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00750-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Estacio RO, Jeffers BW, Hiatt WR, Biggerstaff SL, Gifford N, Schrier RW. The effect of nisoldipine as compared with enalapril on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:645–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803053381003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists C. Effects of Different Blood Pressure-Lowering Regimens on Major Cardiovascular Events in Individuals With and Without Diabetes Mellitus: Results of Prospectively Designed Overviews of Randomized Trials. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1410–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nobakhthaghighi N, Kamgar M, Bekheirnia MR, McFann K, Estacio R, Schrier RW. Relationship between urinary albumin excretion and left ventricular mass with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1187–90. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00750306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy-II: Maintenance of vascular graft or arterial patency by antiplatelet therapy. Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Bmj. 0 19;4; 308:159–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee. Lancet. 1996;348:1329–39. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)09457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bhatt DL, Marso SP, Hirsch AT, Ringleb PA, Hacke W, Topol EJ. Amplified benefit of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardio. 2002;90:625–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02567-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Antithrombotic Trialists Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Final report on the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians’ Health Study. Steering Committee of the Physicians’ Health Study Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:129–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907203210301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1849–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fuller JH, Shipley MJ, Rose G, Jarrett RJ, Keen H. Mortality from coronary heart disease and stroke in relation to degree of glycaemia: the Whitehall study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;287:867–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6396.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dilley J, Ganesan A, Deepa R, Deepa M, Sharada G, Williams OD, et al. Association of A1C with cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome in Asian Indians with normal glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1527–32. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Coutinho M, Gerstein HC, Wang Y, Yusuf S. The relationship between glucose and incident cardiovascular events. A metaregression analysis of published data from 20 studies of 95,783 individuals followed for 12.4 years. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:233–40. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Selvin E, Marinopoulos S, Berkenblit G, Rami T, Brancati FL, Powe NR, et al. Meta-analysis: glycosylated hemoglobin and cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:421–31. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-6-200409210-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.[No author listed]. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352:837–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Reichard P, Nilsson BY, Rosenqvist U. The effect of long-term intensified insulin treatment on the development of microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:304–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307293290502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lawes CM, Parag V, Bennett DA, Suh I, Lam TH, Whitlock G, et al. Blood glucose and risk of cardiovascular disease in the Asia Pacific region. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2836–42. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Skyler JS. Effects of glycaemic control on diabetes complications and on the prevention of diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2004;22:162–66. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Narayan KMV, Zhang P, Kanaya AM, Williams DE, Engelgau MM, Imperatore G, et al. Diabetes: The Pandemic and Potential Solutions. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, et al., editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. tables 30.33 and 30.34. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Turner R, Cull C, Holman R. United Kingdom prospective diabetes study 17: a 9-year update of a randomized, controlled trial on the effect of improved metabolic control on complications in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:136–45. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-1_part_2-199601011-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, Goff DC, Jr, Bigger JT, Buse JB, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2545–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Billot L, Woodward M, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2560–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, Reda D, Emanuele N, Reaven PD, et al. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:129–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Buse JB, Rosenstock J. Prevention of cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus: trials on the horizon. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2005;34:221–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Facts & Figures: The costs of diabetes. International Diabetes Federation. The human, social & economic impact of diabetes. Available at: http://www.idf.org/home/index.cfm?node=41, accessed on February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Vinik AI, Vinik E. Prevention of the complications of diabetes. Am J Managed Care. 2003;9(3 Suppl):S63–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Srikanth S, Deedwania P. Comprehensive risk reduction of cardiovascular risk factors in the diabetic patient: an integrated approach. Cardiol Clin. 2005;23:193–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, Genuth SM, Lachin JM, Orchard TJ, et al. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2643–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1577–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ray KK, Seshasai SR, Wijesuriya S, Sivakumaran R, Nethercott S, Preiss D, et al. Effect of intensive control of glucose on cardiovascular outcomes and death in patients with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1765–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60697-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Turnbull F, Abraira C, Anderson R, Byington R, Chalmers J, Duckworth W, et al. Intensive glucose control and macrovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2288–98. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Skyler JS, Bergenstal R, Bonow RO, Buse J, Deedwania P, Gale EA, et al. Intensive glycemic control and the prevention of cardiovascular events: implications of the ACCORD, ADVANCE, and VA diabetes trials: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and a scientific statement of the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:187–92. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Haffner SJ, Cassells H. Hyperglycemia as a cardiovascular risk factor. Am J Med. 2003;115(Suppl 8A):6S–11S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Levitan EB, Song Y, Ford ES, Liu S. Is nondiabetic hyperglycemia a risk factor for cardiovascular disease? A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2147–55. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.19.2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wagenknecht LE, Zaccaro D, Espeland MA, Karter AJ, O’Leary DH, Haffner SM. Diabetes and progression of carotid atherosclerosis: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1035–41. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000072273.67342.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Vijan S, Hayward RA. Treatment of Hypertension in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Blood Pressure Goals, Choice of Agents, and Setting Priorities in Diabetes Care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:593–602. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-7-200304010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.American Diabetes A. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes--2008. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 1):S12–54. doi: 10.2337/dc08-S012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gaede P, Vedel P, Larsen N, Jensen GV, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Multifactorial intervention and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:383–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Clinical Trial Service Unit & Epidemiological Studies Unit. HPS2-THRIVE Press Release: Launch of major international study to test new drug combination to cut cardiovascular disease. University of Oxford. [May 31, 2006; http://www.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/pressreleases/2006-05-31/hps2-thrive-press-release Accessed June 30, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Deedwania PC. Diabetes and hypertension, the deadly duet: importance, therapeutic strategy, and selection of drug therapy. Cardiol Clin. 2005;23:139–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Nagpal J, Bhartia A. Quality of diabetes care in the middle- and high-income group populace: the Delhi Diabetes Community (DEDICOM) survey. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2341–8. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Raheja BS, Kapur A, Bhoraskar A, Sathe SR, Jorgensen LN, Moorthi SR, et al. DiabCare Asia - India Study: diabetes care in India--current status. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:717–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Brown JB, Nichols GA, Perry A. The burden of treatment failure in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1535–40. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.7.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Stanton MW. Improving care for diabetes patients through intensive therapy and a team approach Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality November 2001. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/ research/diabria/diabria2.htm, accessed on July 5, 2008. [Google Scholar]