Abstract

Aims

Nitrite (NO2−), now regarded as an endocrine reserve of nitric oxide (NO), is bioactivated by nitrite reductase enzymes to mediate physiological responses. In blood, haemoglobin (Hb) catalyses nitrite reduction through a reaction modulated by haem redox potential and oxygen saturation, resulting in maximal NO production around the Hb P50. Although physiological studies demonstrate that Hb-catalysed nitrite reduction mediates cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-dependent vasodilation, the NO-scavenging effects of Hb raise questions about how NO generated from this reaction escapes the Hb molecule to signal at distant targets. Here, we characterize the NO-generating properties of Hb using the cGMP-independent and NO-dependent inhibition of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase.

Methods and results

Using a novel technique to measure respiratory inhibition of isolated rat mitochondria, we provide evidence that the reduction of nitrite by intact red blood cells (RBCs) and Hb generates NO, which inhibits mitochondrial respiration. We show that allosteric modulators, which reduce the haem redox potential and stabilize the R state of Hb, regulate the ability of this reaction to inhibit respiration. Finally, we find that the rate of NO generation increases with the rate of Hb deoxygenation, explained by an increase in the proportion of partially deoxygenated R-state tetramers, which convert nitrite to NO more rapidly.

Conclusion

These data reveal redox and allosteric mechanisms that control Hb-mediated nitrite reduction and regulation of mitochondrial function, and support a role for Hb-catalysed nitrite reduction in hypoxic vasodilation.

Keywords: Haemoglobin, Nitrite, Mitochondria, Cytochrome c oxidase, Hypoxic vasodilation

1. Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) plays an integral role in sustaining vascular homeostasis on a number of levels including maintaining vascular tone, inhibiting thrombosis, and regulating the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules. For years, NO was considered to be strictly a paracrine signalling molecule whose short half-life, limited diffusibility, and rapid reaction rate with haem proteins made it an optimal signalling molecule for such pathways as the activation of soluble guanylate cyclase leading to cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-dependent vasodilation. However, accumulating evidence demonstrates that the molecule nitrite (NO2−) represents a circulating reservoir of endocrine NO that is responsible for mediating responses, such as hypoxic vasodilation.1–3

Nitrite, the one electron oxidation product of NO, is a dietary component and is present basally in red blood cells (RBC; 290 nM) and plasma (120 nM).4 In tissues, nitrite is reduced along a physiological oxygen and pH gradient by a number of enzymes to mediate responses such as the modulation of protein expression,5 angiogenesis,6 regulation of metabolism,7–9 and cytoprotection after ischaemia/reperfusion injury.10–17

In the blood, haemoglobin (Hb) is the predominant nitrite reductase and its reaction with nitrite has been proposed as a mechanism of hypoxic vasodilation.18–22 In this reaction, deoxygenated ferrous haemoglobin (deoxyHb) reduces nitrite in the presence of a proton, yielding NO and methaemoglobin (metHb) (Reaction 1)23,24:

| (1) |

The NO generated binds unreacted deoxyHb to form iron–nitrosyl Hb (Reaction 2):

| (2) |

Biochemical analysis of this reaction has demonstrated that Hb-catalysed nitrite reduction is regulated by oxygen and pH, as well as by the allosteric structural transition of the tetrameric Hb molecule.19,20,22 This allosteric regulation is driven by the balance of vacant-binding sites for nitrite on the Hb tetramer, which are maximal in the deoxygenated (T) state, vs. the ability of the haem to donate an electron to nitrite, which is optimal in the oxygenated (R) state.20 This results in maximal Hb-catalysed nitrite reduction occurring at the oxygen tension at which the Hb molecule is half-saturated with oxygen (P50).20 These biochemical observations are supported by in vitro aortic ring experiments in which physiological concentrations of nitrite vasodilate rings only in the presence of deoxyHb, and this vasodilation is initiated at the Hb P50.19 Despite accumulating evidence for the role of nitrite reduction in mediating hypoxic vasodilation, scepticism remains as to whether this reaction can generate NO that is able to leave the Hb molecule to signal at distant targets. Thus, a physiologically relevant, vessel-independent method is needed to measure NO generated from this reaction.

Mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) is responsible for 99% of oxygen consumption in the body and is the predominant target for NO within mitochondria. The active site of this enzyme, the binuclear centre, consists of haemea3 and copperB, to which oxygen binds and is reduced to water to act as the terminal electron acceptor in the respiratory chain. The binuclear centre is also a major position of respiratory regulation due to the ability of NO to bind a reduced catalytic intermediate of this site, precluding the binding of oxygen, and thus resulting in the inhibition of mitochondrial respiration.25,26 Importantly, this NO-dependent inhibition of respiration is more potent as oxygen concentration is decreased, such that nanomolar concentrations of NO elicit significant inhibition in hypoxia.27,28 Furthermore, this inhibition is completely reversible.26,28 Physiologically, this phenomenon is involved in a number of processes including the extension of tissue oxygen gradients,29,30 regulation of HIF-1α,31 and the modulation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation32 for signalling. However, the ability to measure respiratory inhibition in isolated mitochondria in vitro and the sensitivity of respiration to low levels of NO in hypoxia make it ideal for its use as an indicator of NO generation.

Herein, using NO-dependent mitochondrial inhibition as a unique NO biosensor, we demonstrate that RBC and Hb-catalysed nitrite reduction result in physiologically relevant levels of bioavailable NO. We describe two methods of measuring hypoxic mitochondrial respiratory inhibition, a deoxygenating kinetic system and an open-flow assay, and use these systems to demonstrate the modulation of this nitrite reductase activity by oxygen and allosteric modulators of Hb.

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

All reagents were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Mitochondrial isolation and respiration

Liver mitochondria were isolated as described previously9 from male Sprague Dawley rats (250–350 g) in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh and in compliance with the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23).

Respiration was measured using a Clark-type oxygen electrode (Instech, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA) mounted in a sealed chamber, which was stirred at 37°C as outlined in Supplementary material online, Methods.

2.3. Cardiac cGMP

Isolated rat hearts were perfused with nitrite or RBCs in hypoxic buffer (Krebs–Hanseleit bubbled with 5%CO2/94% N2/1% O2 gas). Hearts were perfused for 5 min and then flash-frozen and homogenized. cGMP levels were measured by competition ELISA using a kit (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

2.4. RBCs and Hb

Healthy human RBCs were acquired after informed consent in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of the NIH and the University of Pittsburgh and in compliance with the Helsinki Agreement. RBCs were washed with PBS at pH 7.4 and used immediately.

Hb was prepared by hypotonically lysing RBCs, discarding the membrane fraction, and then dialysing. Hb was treated with modulators as described previously20 and as outlined in Supplementary material online, Methods.

2.5. Statistics

All data are means ± SEM. Statistical differences between groups were determined by non-parametric Mann–Whitney analysis. Statistical significance was determined as P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Nitrite inhibits mitochondrial respiration in the presence of deoxygenated RBCs

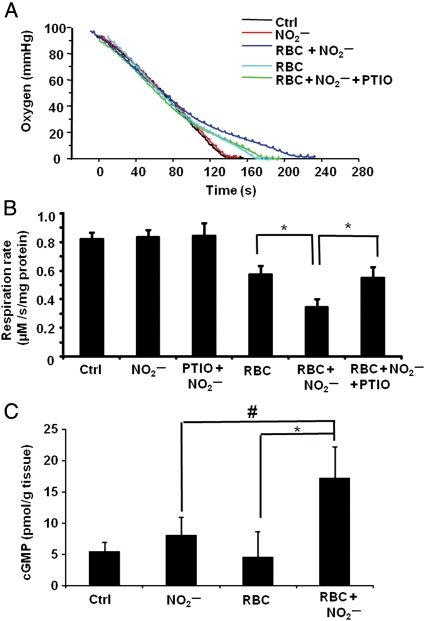

In experiments to determine whether nitrite could be reduced to NO by deoxygenated RBCs and subsequently inhibit respiration, mitochondria were incubated with RBCs and stimulated to respire. Mitochondria, alone or in the presence of nitrite (0–40 µM), consumed oxygen at a constant rate until the respiratory chamber became anoxic. In the presence of RBCs (0.3% haematocrit − 0.3% of the reaction mixture volume, resulting in ∼50 µM haem) alone, the rate of oxygen consumption appeared to decrease as the oxygen tension fell below 20% (40 mmHg) (Figure 1A). This effect is consistent with oxygen offloading from the RBCs as the cells become deoxygenated, and was absent when fully oxidized RBCs (metRBCs) were used (data not shown). In the presence of RBCs and nitrite (20 µM), the rate of mitochondrial oxygen consumption measured below 20 mmHg was significantly decreased (0.35 ± 0.05 µM O2/s/mg protein) compared with RBCs alone (0.58 ± 0.06 µM O2/s/mg protein), indicative of respiratory inhibition. This inhibition occurred only below 28 mmHg, consistent with a maximal rate of nitrite reduction and NO generation at the P50 of the RBCs. This nitrite-mediated inhibition of respiration was completely reversed by the NO scavenger C-PTIO (100 µM), confirming that the species generated was NO and that inhibition occurred through the reversible binding to cytochrome c oxidase (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1.

Deoxygenated RBCs reduce nitrite to NO and inhibit respiration. (A) Representative respiration trace of mitochondria (2 mg/mL) alone (black) or with RBCs (0.35% haematocrit), with nitrite added (20 µM; red), or with RBCs and nitrite (blue). Green trace shows mitochondria incubated with C-PTIO (100 µM) and RBCs with nitrite added. Nitrite was added at 70% oxygen tension. (B) Quantitation of the respiration rate at 20 mmHg O2. (C) Levels of cGMP in hearts perfused with hypoxic buffer (Ctrl), nitrite (30 µM), RBCs (0.3% haematocrit), or nitrite with RBCs. Data are means of five independent experiments ± SEM. *P < 0.001; #P < 0.05.

To validate this experimental model, another bioassay for NO production was used. Isolated rat hearts were perfused with hypoxic (1% O2) buffer containing nitrite, RBCs, or nitrite and RBCs together. Cardiac cGMP levels were measured as a marker of NO and showed a significant increase only after perfusion with nitrite and RBCs together, confirming that deoxygenated RBCs catalyse the reduction of nitrite to NO (Figure 1C).

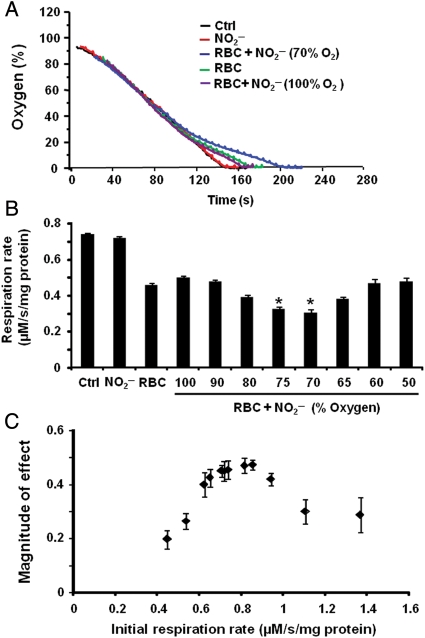

Characterization of the mitochondrial experimental system demonstrated that RBC-dependent, nitrite-mediated inhibition of respiration was dependent on the time of nitrite addition in relation to the rate of RBC and mitochondrial deoxygenation. The addition of nitrite (20 µM) to the chamber containing mitochondria and RBCs (0.3% haematocrit) at various stages of deoxygenation resulted in variable extents of inhibition. The introduction of nitrite in the system at 70% oxygen demonstrated a significant inhibition, whereas incubation of nitrite with RBCs from the beginning of the experiment failed to inhibit respiration (Figure 2A). The magnitude of effect was greatest when nitrite was introduced at 60–70% oxygen tension, and no significant effect on respiration was observed with nitrite addition above 75% or below 50% oxygen (Figure 2B). The lack of effect with early nitrite addition is likely due to the consumption of nitrite by its reaction with oxyhaemoglobin. This was confirmed by absorption spectra of the RBCs from the reaction mixture taken at the end of the experiment, which showed that the RBCs were completely oxidized (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Deoxygenation rate affects nitrite–RBC-dependent respiratory inhibition. (A) Respiratory traces of mitochondria (2.2 mg/mL) alone (black), treated with nitrite (20 µM; red) or incubated with RBCs (0.3% haematocrit; green). Mitochondria incubated with RBCs were incubated with nitrite from 100% oxygen (purple) or at 70% oxygen (blue). (B) Quantification of several traces like those in (A) in which nitrite was injected into the chamber at different oxygen tensions. (C) The magnitude of the inhibitory effect (the difference in rate at 20% oxygen of the mitochondria incubated with RBCs alone and those incubated with RBCs and treated with nitrite) in mitochondria with differing respiratory rates. Data in (B) and (C) are means of four independent experiments in each group ± SEM. *P < 0.01 with respect to RBC alone.

The importance of the rate of deoxygenation was corroborated by comparing nitrite–RBC-dependent inhibition of respiration in mitochondrial preparations with differing initial respiratory rates (measured before the addition of RBCs or treatment with nitrite). The magnitude of RBC–nitrite-mediated inhibition, quantified as the difference in rate between the mitochondria incubated with RBCs alone and RBCs in the presence of nitrite, was biphasic (Figure 2C).

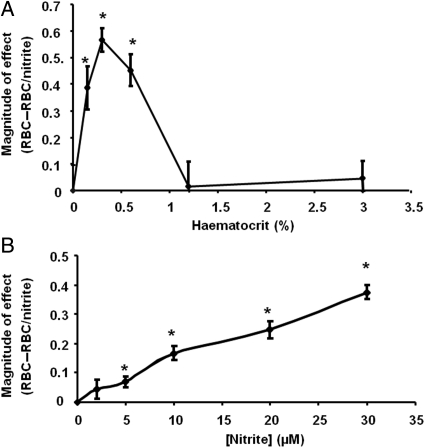

Next, the effect of haematocrit and nitrite concentration on the inhibition of respiration was tested. The effect of haematocrit was biphasic, showing an increase in effect at low haematocrits, and a peak at 0.35% haematocrit, after which the effect decreased (Figure 3A). This is consistent with an NO-scavenging effect at high haematocrits. The extent of inhibition in the presence of RBCs (0.35% haematocrit) was dependent on the concentration of nitrite between 2.5 and 30 µM nitrite (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of respiration is dependent on haematocrit and nitrite concentration. (A) The magnitude of inhibition in the presence of mitochondria (2 mg/mL), nitrite (20 µM), and increasing haematocrit (0.1–3%). (B) Inhibition of respiration of mitochondria (2 mg/mL) in the presence of RBCs (0.35% haematocrit) and varying concentrations of nitrite (2.5–30 µM). *P ≤ 0.01 compared with control condition [mitochondria without RBCs in (A) and without nitrite in (B)]. Data are means ± SEM of four (A) and five (B) independent experiments.

3.2. The open-flow model of hypoxic inhibition

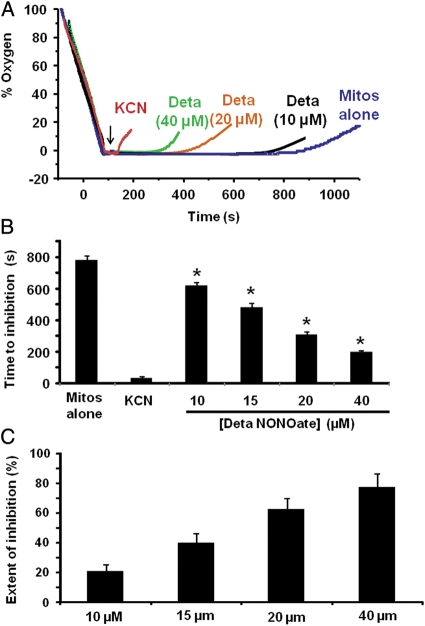

We next determined whether mitochondria could be used as a sensor for NO generated by nitrite reduction catalysed by free Hb. The assay described above was ineffective for measuring Hb-catalysed nitrite reduction because the much higher oxygen affinity of cell-free Hb (P50 ∼10 mmHg) rendered it impossible to collect data between the time of Hb deoxygenation and anoxia. To circumvent this problem, a new assay system was developed in which respiring mitochondria were allowed to make the chamber anoxic. At the point of anoxia, the chamber was opened and equilibrated with room air. Although oxygen diffusion from the air into the chamber was constant, no change was observed in the electrode trace due to the rapid respiratory rate of the mitochondria. In this ‘open flow' model, mitochondria maintained anoxia in the chamber until substrate was exhausted. Once respiratory substrate was exhausted, the chamber accumulated oxygen. When an irreversible respiratory inhibitor, cyanide, was added to completely inhibit respiration, oxygen diffusing into the chamber was not consumed and accumulated within the chamber immediately after the addition, causing the oxygen trace to deviate from zero (Figure 4A). The addition of an NO donor (DetaNONOate) showed a lag time before the accumulation of oxygen in the chamber. The time between the addition of the NO donor and the deviation of the trace from anoxia (‘time to inhibition') was representative of partial inhibition of respiration and inversely correlated with the concentration of NO donor (Figure 4A and B). To rule out the possibility that NO release by the donor was delayed in this system, NO release from the donor was measured polarographically in the absence of mitochondria. As expected, NO gradually accumulated in the chamber after the donor was added, consistent with the immediate decay of the donor (Supplementary material online, Figure S1). When the extent of inhibition was calculated based on the time to inhibition compared with cyanide-mediated inhibition (100% inhibition) and exhaustion of substrate (0% inhibition), NO showed a concentration-dependent inhibition curve (Figure 4C). It is important to note that although micromolar concentrations of the NO donor were used, the actual concentration of NO in the chamber was much lower due to the half-life of the donor (20 h at 37°C). Calculation of NO concentration from the half-life of the donor suggests that inhibition was detected by the oxygen electrode when ∼75–100 nM of NO accumulated in the chamber, consistent with the range of NO previously reported to inhibit respiration in isolated mitochondria.27,28,33

Figure 4.

Open-flow assay for hypoxic mitochondrial inhibition. Mitochondria were stimulated to, and allowed to, make the chamber anoxic. Increasing concentrations of DetaNONOate (0–40 µM) were injected into the chamber (denoted by arrow) and then the chamber lid was opened. (A) Representative mitochondrial respiratory traces with mitochondria alone, treated with potassium cyanide (100 µM; KCN), or DetaNONOate (concentration as labelled). (B) The time to inhibition (time from the removal of the chamber lid to the deviation of the oxygen trace from zero) of traces in (A). (C) The extent of inhibition with increasing concentrations of DetaNONOate for traces similar to those in (A), calculated from the measured time to inhibition. *P < 0.001 compared with mitos alone. Data are means of five independent experiments.

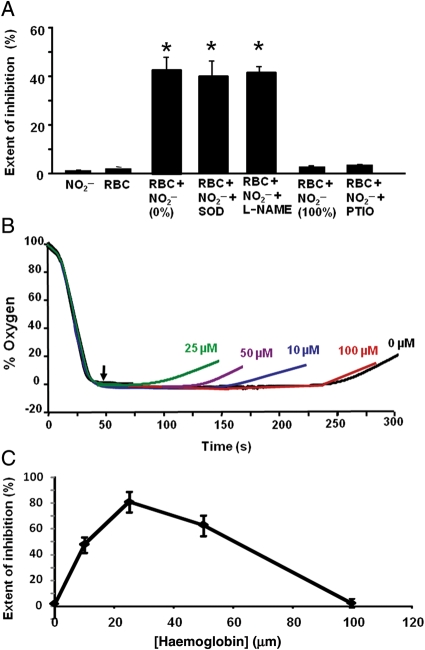

To further validate this assay system, isolated mitochondria were first incubated with RBCs. In this assay, nitrite (20 µM) or RBCs (0.35% haematocrit) alone had no significant effect on the time to mitochondrial inhibition. However, oxygen accumulation in the chamber occurred significantly earlier when mitochondria were incubated with RBCs and nitrite was added to the deoxygenated chamber, indicative of respiratory inhibition (Figure 5A). Similar results were observed when heart mitochondria respiring on pyruvate were used instead of liver mitochondria, demonstrating that the effect is not specific to liver mitochondria or a particular respiratory substrate (Supplementary material online, Figure S2). Interestingly, in the open-flow system, like the deoxygenation assay, nitrite was only effective in inhibiting respiration when added to the deoxygenated chamber, as the incubation of RBCs with nitrite from the beginning of the assay had no effect on respiration. Nitrite–RBC-mediated inhibition of respiration was not significantly changed by the presence of superoxide dismutase (100 µM) or treatment with the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor L-NAME (200 µM), ruling out a role for ROS or NOS in this effect. Addition of C-PTIO to the incubation prevented the inhibition of respiration (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Cell-free Hb catalyses nitrite reduction and respiratory inhibition. (A) Intact RBCs (0.35% haematocrit) were incubated with mitochondria (2.3 mg/mL), and in some cases with superoxide dismutase (SOD 100 µM) or L-NAME (L-NAME 200 µM). Nitrite was added either when the chamber was deoxygenated (0%) or in the initial incubation (100%). The extent of inhibition was calculated from the time of removal of the chamber lid to the deviation of the trace from zero oxygen. (B) Representative traces of mitochondria (2 mg/mL) incubated with varying concentrations of cell-free Hb and treated with nitrite (20 µM) once deoxygenated (denoted by arrow). (C) Quantification of the extent of inhibition of respiration from several traces similar to those shown in (B). *P < 0.001. Data are means of five independent experiments.

To determine whether deoxygenated free Hb could reduce nitrite to NO and subsequently inhibit mitochondrial respiration, purified Hb (10–200 µM) was incubated with mitochondria. The mitochondria showed no respiratory inhibition in the presence of nitrite or Hb alone. However, when nitrite was added to the incubation containing mitochondria and Hb, significant inhibition of respiration (79 ± 8%) was observed. Addition of nitrite to mitochondria incubated with varying concentrations of Hb demonstrated a biphasic response, with the greatest effect at 25 µM Hb (Figure 5B and C).

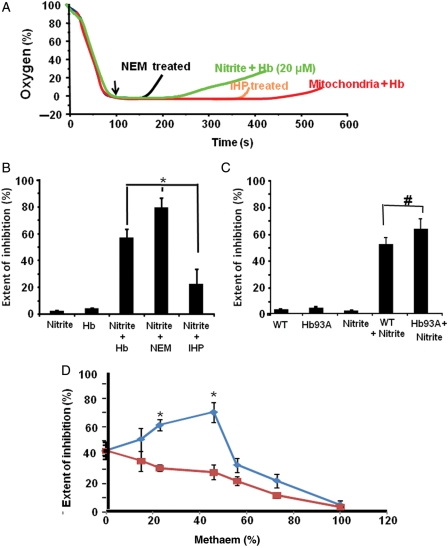

3.3. Allosteric modulators regulate Hb–nitrite-mediated respiratory inhibition

The rate of Hb's nitrite reductase activity is regulated by its allosteric structural transition between the deoxygenated (T) and oxygenated (R) state. This regulation is due to the balance between the necessity for nitrite-binding sites on the Hb tetramer, which are maximal in T state, vs. the ability of the haem to donate an electron to nitrite (a negative redox potential), which is maximal in the R-state tetramer.20,22 Hence, the reduction of nitrite with 100% deoxyHb (T state) is relatively slow (bimolecular rate constant: 0.17 vs. ∼6 M−1 s−1 in R state), but as the reaction proceeds, products of the reaction (met and iron–nitrosyl haem) stabilize the R-state tetramer and accelerate the rate of reaction.20,34

To determine whether allosteric modulation of the Hb molecule could alter the rate of deoxyHb-catalysed nitrite reduction and change the extent of mitochondrial inhibition, mitochondria were incubated with deoxyHb treated with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), which decreases the haem redox potential (E1/2 = 85 vs. 45 m/V for untreated Hb) and accelerates the Hb–nitrite reaction.19,20 Addition of nitrite to this incubation increased the extent of inhibition (80 ± 7%) in comparison with untreated Hb (57 ± 6%), consistent with an increased rate of nitrite reduction (Figure 6A and B). In contrast, inositol hexophosphate (IHP) increases the redox potential of Hb (E1/2 = 135 m/V) and thus decreases the rate of Hb-catalysed nitrite reduction.19,20 Consistent with this, nitrite elicited a decreased extent of inhibition (22 ± 11%) when mitochondria were incubated in the presence of IHP-treated Hb (Figure 6A and B).

Figure 6.

Allosteric modulation of the Hb molecule regulates mitochondrial inhibition. (A) Representative respiratory inhibition traces of mitochondria (2 mg/mL) incubated with either untreated, or NEM-treated, or IHP-treated Hb. Arrow denotes the time of nitrite (20 µM) addition. (B) The extent of inhibition calculated from traces similar to those shown in (A). (C) The extent of respiratory inhibition of mitochondria incubated with wildtype Hb or that in which the B93cys is replaced with alanine with and without the addition of nitrite (10 µM). (D) The extent of inhibition of mitochondria incubated with partially oxidized Hb tetramers (blue) or a mixture of deoxyHb and metHb made by mixing 100% deoxy and 100% metHb tetramers (red). *P < 0.001, #P < 0.05; data are means of four independent experiments.

The cysteine-93 residue on the beta chain of the Hb tetramer regulates haem redox potential. To test whether the β93cys is involved in hypoxic NO generation from nitrite, mitochondria were incubated with recombinant mouse Hb in which the β93cys was replaced with alanine.19,35 Addition of nitrite to the incubation containing the β93 alanine mutant Hb resulted in a greater extent of respiratory inhibition (66 ± 6%) than in the presence of wildtype Hb (54 ± 4%) (Figure 6C). These studies indicate that cysteine modification or mutation increases the NO production from nitrite, and indicates that an S-nitrosothiol is not a required intermediate in NO formation from nitrite.

To determine whether stabilization of R-state Hb could increase the rate of nitrite reduction and increase the extent of mitochondrial inhibition, fully oxygenated Hb was treated with low concentrations of the NO donor ProliNONOate to make partial methaem R-state tetramers (ferric Hb has R-state character). Addition of nitrite to mitochondria incubated with partially oxidized Hb showed a biphasic response in the extent of inhibition of respiration, with low concentrations of methaem (4–42%) increasing inhibition and concentrations >56% decreasing inhibition (Figure 6D). This is explained by the stabilization of R-state character by mixed hybrid tetramers containing both ferric and ferrous Hb, leading to an increased nitrite reduction rate at low methaem concentrations, whereas at higher concentrations of methaem, the rate of nitrite reduction was decreased by a lack of nitrite-binding sites. As a control, this experiment was repeated using partially oxidized Hb mixtures obtained by mixing different ratios of fully oxidized (100% met) Hb with fully deoxygenated and reduced Hb tetramers. Addition of nitrite to mitochondria incubated with these mixtures showed a significantly different result compared with the mixed tetramers. As methaem percentage was increased, the extent of inhibition was decreased. This was due to the fact that in this case, increasing the concentration of methaem results solely in a decrease in nitrite-binding sites (Figure 6D).

4. Discussion

Here, we have described two assay systems in which we utilize inhibition of mitochondrial respiration as a sensor for NO generated by Hb-catalysed nitrite reduction. We have exploited this biological response to demonstrate that (i) the Hb-catalysed nitrite reduction generates bioavailable NO that is able to modulate distant targets outside the RBC and (ii) the allosteric modulation of the Hb tetramer that increases the R-state character and increases the nitrite reductase reaction rate increases NO signalling.

The data presented here are the first to use a physiologically relevant, cGMP-independent method of confirming changes in NO production rates with allosteric modulation of Hb-catalysed nitrite reduction. This mitochondrial assay system provides several advantages over the detection of NO by intracellular cGMP. The major advantage of isolated mitochondria is their relative lack of endogenous nitrite reductase activity in comparison with cells which may contain several nitrite reductase enzymes (e.g. myoglobin in myocytes, xanthine oxidase in hepatocytes) that could confound the measurement of NO by Hb-mediated nitrite reduction. In addition, the ability of isolated mitochondria to rapidly and efficiently deoxygenate the experimental system lends to the ease of this assay and the ability to collect kinetic data compared with cell-based cGMP assays.

Although cytochrome c oxidase itself36,37 has been described as a nitrite reductase, this enzyme does not mediate nitrite reduction in the experiments presented here, based on the lack of effect of nitrite alone on mitochondrial respiration. However, it is important to note that at concentrations above 50 µM, a slight but significant inhibitory effect on respiration was observed in the presence of nitrite alone and in the absence of other nitrite reductases. This effect has previously been attributed to the direct binding of nitrite to cytochrome c oxidase, and it is possible that this binding leads to the production of NO. Indeed a similar method has been utilized to demonstrate that high micromolar concentrations of nitrite inhibit plant mitochondria during hypoxia.38

A major strength of this technique is its ability to detect low concentrations of NO due to the sensitivity of mitochondrial respiration to NO. In the open-flow method described here, significant inhibition of respiration is required to sufficiently alter the rate of oxygen accumulation in the chamber enough to detect respiratory inhibition. We used the NO donor DetaNONOate to calculate that in the conditions used, ∼75–100 nM of NO is required to alter respiratory rate to a sufficient level to detect inhibition. Based on the accepted IC50 of NO for cytochrome c oxidase (100 nM at 5–10 µM O2) in isolated mitochondria,27,28 we estimate that at this level of hypoxia, 100 nM of NO results in an ∼60–70% of respiratory inhibition. While this is a high percentage of respiratory inhibition, it is important to note that the ability to detect 100 nM NO renders this system relatively sensitive in comparison with other methods.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the infusion of nitrite into the human forearm or the nebulization of nitrite in hypoxic sheep results in the dilation of the systemic and pulmonary vasculature, respectively.18,39 Moreover, these studies demonstrate that this vasodilatory response is mediated through the reaction of nitrite with Hb. Despite these studies, a principal challenge to the model of Hb-catalysed nitrite reduction as a mediator of hypoxic vasodilation is that the rapid reaction of NO with vicinal deoxyHb would preclude the escape of NO from the RBC. In the current studies, nitrite reduction catalysed by both RBCs and Hb was able to inhibit respiration, suggesting that at least 100 nM NO was able to escape haem scavenging within the time scale of the experiment. Given that the concentration of NO required to activate soluble guanylate cyclase is an order of magnitude lower (EC50 = 5–10 nM), these data support the idea that sufficient NO is able to leave the RBC to mediate vasodilation.

Although focus has been placed on the role of RBC-catalysed nitrite reduction in hypoxic vasodilation, this reaction has implications for the regulation of tissue metabolism as well. Hypoxic vasodilation is a fundamental response to a condition in which the metabolic needs of the tissue are greater than the delivery of oxygen to the tissues.40,41 Whereas increased delivery of oxygen is a compensatory mechanism in these conditions, another mechanism may be the downregulation of tissue oxygen consumption. This type of ‘hibernation' response, in which metabolism is completely shut down during ischaemia, has been described in the heart.42,43 Similarly, in the vessel, during hypoxia, a small but significant decrease in oxygen consumption may prevent complete metabolic stress. Here, we have shown that nitrite–Hb-dependent inhibition of respiration can occur in both heart and liver mitochondria, suggesting that nitrite–Hb-dependent modulation of respiration may be a common mechanism in all organ systems. Consistent with the idea of downregulation of oxygen consumption without compromising energy production, it has been shown that NO can inhibit respiration by ∼35% without significantly altering energy production.33 Physiologically, an oxygen-sensing mechanism that not only leads to the delivery of more oxygen, but also decreases the necessity for oxygen may be an optimal method for hypoxic adaptation.

Beyond vasodilation and modulation of metabolism, NO mediates a number of vascular responses including inhibition of platelet aggregation. The major source of NO in the vessel is generally regarded to be the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). However, since oxygen is required for eNOS-dependent NO production, enzymatic NO generation becomes limited in hypoxic conditions.44 In these conditions, Hb-catalysed nitrite reduction may represent an integral source of NO for the maintenance of vessel homeostasis. We have shown previously that the plasma protein ceruloplasmin oxidizes NO to nitrite in the blood.45 Hence, a cycle may exist in which eNOS-generated NO is oxidized to nitrite in normoxia, and this nitrite reserve is reduced to NO by the RBC in hypoxia. This cycle may be particularly important in maintaining NO homeostasis for circulating cells such as platelets, which contain eNOS and also interact with RBCs.

In summary, we have described a new method of detecting NO generation from the reduction of nitrite using the inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase as a physiological biosensor. Using this method, we have demonstrated here that NO bioavailability from RBC and Hb-catalysed nitrite reduction is regulated by oxygen and allosteric modulation of the Hb molecule. As new data emerge about existing nitrite reductases and novel nitrite reductase systems are discovered, this method can serve as a valuable tool for the physiological detection of NO.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Conflict of interest: M.T.G. is listed as a co-inventor on a US Government Patent for the use of nitrite salts for cardiovascular indications.

Funding

This work was supported by the Institute of Transfusion Medicine (M.T.G.), the Haemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania (S.S. and M.T.G.), the National Institutes of Health (1R01HL096973 to S.S. and M.T.G.), and by the American Heart Association (09SDG2150066 to S.S.).

References

- 1.Lundberg JO, Gladwin MT, Ahluwalia A, Benjamin N, Bryan NS, Butler A, et al. Nitrate and nitrite in biology, nutrition and therapeutics. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:865–869. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:156–167. doi: 10.1038/nrd2466. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Faassen EE, Bahrami S, Feelisch M, Hogg N, Kelm M, Kim-Shapiro DB, et al. Nitrite as regulator of hypoxic signaling in mammalian physiology. Med Res Rev. 2009;29:683–741. doi: 10.1002/med.20151. doi:10.1080/02841860802247664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dejam A, Hunter CJ, Pelletier MM, Hsu LL, Machado RF, Shiva S, et al. Erythrocytes are the major intravascular storage sites of nitrite in human blood. Blood. 2005;106:734–739. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0567. doi:10.1001/jama.294.19.2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryan NS, Fernandez BO, Bauer SM, Garcia-Saura MF, Milsom AB, Rassaf T, et al. Nitrite is a signaling molecule and regulator of gene expression in mammalian tissues. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:290–297. doi: 10.1038/nchembio734. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar D, Branch BG, Pattillo CB, Hood J, Thoma S, Simpson S, et al. Chronic sodium nitrite therapy augments ischemia-induced angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7540–7545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711480105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsen FJ, Weitzberg E, Lundberg JO, Ekblom B. Effects of dietary nitrate on oxygen cost during exercise. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2007;191:59–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01713.x. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(01)02986-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen FJ, Weitzberg E, Lundberg JO, Ekblom B. Dietary nitrate reduces maximal oxygen consumption while maintaining work performance in maximal exercise. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.006. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiva S, Huang Z, Grubina R, Sun J, Ringwood LA, MacArthur PH, et al. Deoxymyoglobin is a nitrite reductase that generates nitric oxide and regulates mitochondrial respiration. Circ Res. 2007;100:654–661. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260171.52224.6b. doi:10.1007/s10552-008-9138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker JE, Su J, Fu X, Hsu A, Gross GJ, Tweddell JS, et al. Nitrite confers protection against myocardial infarction: role of xanthine oxidoreductase, NADPH oxidase and K(ATP) channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.07.057. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryan NS, Calvert JW, Elrod JW, Gundewar S, Ji SY, Lefer DJ. Dietary nitrite supplementation protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19144–19149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706579104. doi:10.1093/humrep/den271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dezfulian C, Raat N, Shiva S, Gladwin MT. Role of the anion nitrite in ischemia-reperfusion cytoprotection and therapeutics. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.001. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duranski MR, Greer JJ, Dejam A, Jaganmohan S, Hogg N, Langston W, et al. Cytoprotective effects of nitrite during in vivo ischemia-reperfusion of the heart and liver. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1232–1240. doi: 10.1172/JCI22493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez FM, Shiva S, Vincent PS, Ringwood LA, Hsu LY, Hon YY, et al. Nitrite anion provides potent cytoprotective and antiapoptotic effects as adjunctive therapy to reperfusion for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117:2986–2994. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.748814. doi:10.1677/ERC-07-0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiva S, Sack MN, Greer JJ, Duranski M, Ringwood LA, Burwell L, et al. Nitrite augments tolerance to ischemia/reperfusion injury via the modulation of mitochondrial electron transfer. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2089–2102. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070198. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinha SS, Shiva S, Gladwin MT. Myocardial protection by nitrite: evidence that this reperfusion therapeutic will not be lost in translation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2008.05.001. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webb A, Bond R, McLean P, Uppal R, Benjamin N, Ahluwalia A. Reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide during ischemia protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13683–13688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402927101. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4741.2008.00641.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cosby K, Partovi KS, Crawford JH, Patel RP, Reiter CD, Martyr S, et al. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1498–1505. doi: 10.1038/nm954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crawford JH, Isbell TS, Huang Z, Shiva S, Chacko BK, Schechter AN, et al. Hypoxia, red blood cells, and nitrite regulate NO-dependent hypoxic vasodilation. Blood. 2006;107:566–574. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2668. doi:10.1093/humrep/del411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Z, Shiva S, Kim-Shapiro DB, Patel RP, Ringwood LA, Irby CE, et al. Enzymatic function of hemoglobin as a nitrite reductase that produces NO under allosteric control. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2099–2107. doi: 10.1172/JCI24650. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1438.2003.13041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeffers A, Xu X, Huang KT, Cho M, Hogg N, Patel RP, et al. Hemoglobin mediated nitrite activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2005;142:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2005.04.016. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang KT, Keszler A, Patel N, Patel RP, Gladwin MT, Kim-Shapiro DB, et al. The reaction between nitrite and deoxyhemoglobin. Reassessment of reaction kinetics and stoichiometry. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31126–31131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501496200. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks J. The action of nitrite on haemoglobin in the absence of oxygen. Proc R Soc Med. 1937;123:368–382. doi:10.1002/cncr.11634. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doyle MP, Pickering RA, DeWeert TM, Hoekstra JW, Pater D. Kinetics and mechanism of the oxidation of human deoxyhemoglobin by nitrites. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:12393–12398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown GC, Cooper CE. Nanomolar concentrations of nitric oxide reversibly inhibit synaptosomal respiration by competing with oxygen at cytochrome oxidase. FEBS Lett. 1994;356:295–298. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01290-3. doi:10.1007/s10552-010-9524-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cleeter MW, Cooper JM, Darley-Usmar VM, Moncada S, Schapira AH. Reversible inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal enzyme of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, by nitric oxide. Implications for neurodegenerative diseases. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:50–54. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00424-2. doi:10.1080/00016340701446231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brookes PS, Kraus DW, Shiva S, Doeller JE, Barone MC, Patel RP, et al. Control of mitochondrial respiration by NO*, effects of low oxygen and respiratory state. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31603–31609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211784200. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiva S, Brookes PS, Patel RP, Anderson PG, Darley-Usmar VM. Nitric oxide partitioning into mitochondrial membranes and the control of respiration at cytochrome c oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7212–7217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131128898. doi:10.1245/s10434-007-9800-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas DD, Liu X, Kantrow SP, Lancaster JR., Jr. The biological lifetime of nitric oxide: implications for the perivascular dynamics of NO and O2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:355–360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011379598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Victor VM, Nunez C, D'Ocon P, Taylor CT, Esplugues JV, Moncada S. Regulation of oxygen distribution in tissues by endothelial nitric oxide. Circ Res. 2009;104:1178–1183. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197228. doi:10.1080/10937400701876095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mateo J, Garcia-Lecea M, Cadenas S, Hernandez C, Moncada S. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha by nitric oxide through mitochondria-dependent and -independent pathways. Biochem J. 2003;376:537–544. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031155. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brookes P, Darley-Usmar VM. Hypothesis: the mitochondrial NO(*) signaling pathway, and the transduction of nitrosative to oxidative cell signals: an alternative function for cytochrome c oxidase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:370–374. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00805-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brookes PS, Shiva S, Patel RP, Darley-Usmar VM. Measurement of mitochondrial respiratory thresholds and the control of respiration by nitric oxide. Methods Enzymol. 2002;359:305–319. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)59194-1. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grubina R, Huang Z, Shiva S, Joshi MS, Azarov I, Basu S, et al. Concerted nitric oxide formation and release from the simultaneous reactions of nitrite with deoxy- and oxyhemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12916–12927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700546200. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isbell TS, Sun CW, Wu LC, Teng X, Vitturi DA, Branch BG, et al. SNO-hemoglobin is not essential for red blood cell-dependent hypoxic vasodilation. Nat Med. 2008;14:773–777. doi: 10.1038/nm1771. doi:10.1007/s11864-009-0108-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castello PR, David PS, McClure T, Crook Z, Poyton RO. Mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase produces nitric oxide under hypoxic conditions: implications for oxygen sensing and hypoxic signaling in eukaryotes. Cell Metab. 2006;3:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.011. doi:10.1093/humrep/del132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castello PR, Woo DK, Ball K, Wojcik J, Liu L, Poyton RO. Oxygen-regulated isoforms of cytochrome c oxidase have differential effects on its nitric oxide production and on hypoxic signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8203–8208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709461105. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91687-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benamar A, Rolletschek H, Borisjuk L, Avelange-Macherel MH, Curien G, Mostefai HA, et al. Nitrite-nitric oxide control of mitochondrial respiration at the frontier of anoxia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:1268–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.06.002. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hunter CJ, Dejam A, Blood AB, Shields H, Kim-Shapiro DB, Machado RF, et al. Inhaled nebulized nitrite is a hypoxia-sensitive NO-dependent selective pulmonary vasodilator. Nat Med. 2004;10:1122–1127. doi: 10.1038/nm1109. doi:10.1006/gyno.2001.6209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross JM, Fairchild HM, Weldy J, Guyton AC. Autoregulation of blood flow by oxygen lack. Am J Physiol. 1962;202:21–24. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1962.202.1.21. doi:10.1016/S1521-6934(02)00128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tune JD, Gorman MW, Feigl EO. Matching coronary blood flow to myocardial oxygen consumption. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:404–415. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01345.2003. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heusch G, Schulz R, Rahimtoola SH. Myocardial hibernation: a delicate balance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H984–H999. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01109.2004. doi:10.1097/00001648-199907000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ross J., Jr. Myocardial perfusion-contraction matching. Implications for coronary heart disease and hibernation. Circulation. 1991;83:1076–1083. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.3.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dweik RA, Laskowski D, Abu-Soud HM, Kaneko F, Hutte R, Stuehr DJ, et al. Nitric oxide synthesis in the lung. Regulation by oxygen through a kinetic mechanism. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:660–666. doi: 10.1172/JCI1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiva S, Wang X, Ringwood LA, Xu X, Yuditskaya S, Annavajjhala V, et al. Ceruloplasmin is a NO oxidase and nitrite synthase that determines endocrine NO homeostasis. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:486–493. doi: 10.1038/nchembio813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.