Abstract

Context

Weight gain in young adults is an important public health problem and few interventions have been successful.

Background

This pilot study evaluated the preliminary efficacy of two self-regulation approaches to weight-gain prevention: Small Changes (changes in energy balance of roughly 200 kcal/day) and Large Changes (initial weight loss of 5–10 lbs to buffer against future weight gains).

Intervention

Participants were enrolled in 8-week programs teaching Small or Large Changes (SC; LC). Both approaches were presented in a self-regulation framework, emphasizing daily self-weighing.

Design

Randomized controlled pilot study.

Setting/participants

Young adults (N=52) aged 18–35 years (25.6±4.7 years, BMI of 26.7±2.4 kg/m2) were recruited in Providence RI and Chapel Hill NC.

Main outcome measures

Adherence to intervention, weight change, and satisfaction/confidence in approach assessed at 0, 8, and 16 weeks. Data were collected in 2008 and analyzed in 2008–2009.

Results

Participants attended 84% of sessions, and 86.5% and 84.5% of participants completed post-treatment and follow-up assessments, respectively. Participants adhered to their prescriptions. Daily weighing increased markedly in both groups, whereas the eating and exercise changes observed in the SC and LC reflected the specific approach taught. Weight changes were significantly different between groups at 8 weeks (SC= −0.68±1.5 kg, LC= −3.2±2.5 kg, p<0.001) and 16 weeks (SC = −1.5±1.8 kg, LC= −3.5±3.1 kg, p=0.006). Participants in both groups reported high levels of satisfaction and confidence in the efficacy of the approach they were taught.

Conclusions

Both Small and Large Change approaches hold promise for weight-gain prevention in young adults; a fully powered trial comparing the long-term efficacy of these approaches is warranted.

Introduction

Young adults experience the fastest weight gain, averaging 15 kg over 15 years.1–4 These weight gains have been related to the risk of developing a host of medical conditions. Yet, there have been few randomized trials9–12 targeting weight-gain prevention in young adults. Moreover, the two largest, longest prevention trials9,10 found no differences between intervention and control groups, with all groups gaining weight over 3 years.

Given that weight gain in young adults appears to be the typical response to an obesogenic environment, internal regulatory mechanisms do not seem sufficient. Thus, some type of external monitoring and behavioral control appear necessary. Findings suggest13 that daily self-weighing is a key component of self-regulation of weight and is associated with less weight gain over time. Teaching individuals to self-weigh regularly and to use the information to make changes in their behavior has been shown to effectively prevent weight regain14 and may help young adults prevent weight gain.

In using a self-regulation framework for prevention, a key question is what type of behavior changes should be prescribed. One approach is to recommend small daily changes in energy balance. Another approach is to encourage periodic large changes, resulting in modest weight losses to buffer against future weight gain. There is limited support for each approach and to date no study has directly compared them.

The Small Changes approach has been advanced primarily by Hill and colleagues,15–17 who have provided some evidence that small changes in energy balance should be sufficient to prevent weight gain. In one study,17 this approach prevented weight gain in intervention mothers. In another study16 both the small changes and control groups had small comparable weight losses at 6 months. Although the evidence base for this approach is still in its infancy, the concept itself has tremendous intuitive appeal and has been promoted in campaigns (e.g., America on the Move, SmallSteps.gov).

The Large Changes approach has stronger empirical support, coming from both epidemiologic studies18 and from a weight-gain prevention trial19,20 done with more than 500 premenopausal women. In this trial, women in the intervention group were helped to lose 5–15 lbs to offset the weight gain expected to occur with aging. At 5 years, intervention women remained 0.9 kg below baseline, whereas control women had gained 2.4 kg. Although this approach appears promising, it has not been tested in young adults.

To date, no study has directly compared the Small and Large Changes approaches to weight-gain prevention in young adults. The current pilot study was conducted in preparation for a large-scale trial and sought to determine the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of these approaches. Specifically, the goal was to determine whether the approaches would be distinct in implementation, acceptable to participants, and if, as expected, there would be differences in short-term weight losses.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited through advertisements, email blasts, and flyers. Eligible individuals were aged 18–35 years, with a BMI between 23 and 32 kg/m2, and could not have a history of an eating disorder or substance abuse, be in another weight control program, or have lost ≥5% of their body weight within 6 months.

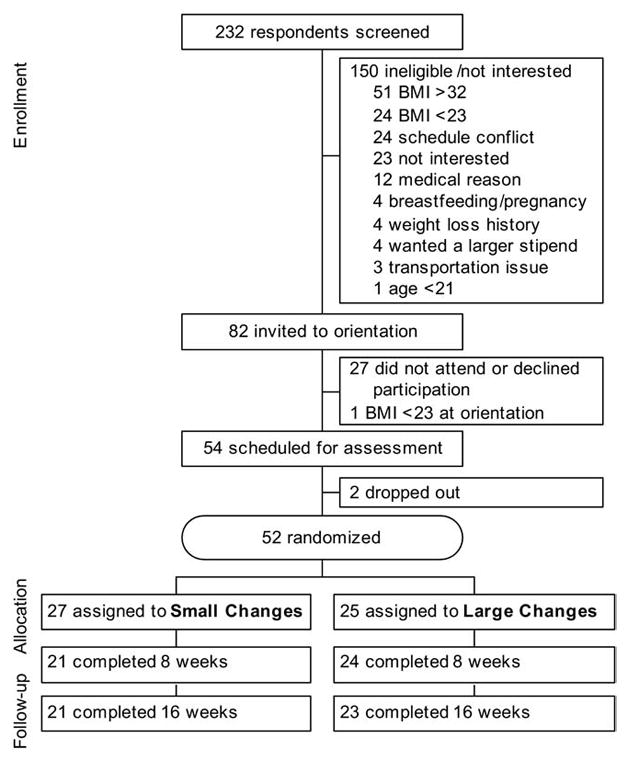

A total of 232 potential participants were screened by phone (Figure 1). Those who were eligible were invited to an orientation where study details were described and informed consent was obtained. Data were collected between January 2008 and June 2008 in Providence RI and Chapel Hill NC.

Figure 1.

Study enrollment and retention

Study Design

Participants were randomly assigned to groups: self-regulation with Large Changes or self-regulation with Small Changes (hereafter referred to as Large and Small Changes or LC and SC, respectively). Both groups attended eight weekly, then two monthly meetings, with assessments at 0, 8, and 16 weeks. Participants were paid $10 and $20 for the 8- and 16-week visits, respectively. The present study was approved by the IRBs at the Miriam Hospital on December 18, 2007, and at UNC at Chapel Hill on November 20, 2007.

Treatment components that were similar across groups

Groups were led by interventionists with master’s degrees in nutrition or health behavior and behavioral weight-loss experience. Participants were taught the core skills that form the basis of behavioral weight control programs (e.g., self-monitoring, stimulus control, problem solving). During the initial 8 weeks, both groups received education on the principles of self-regulation;21 they were taught to weigh themselves daily, to compare their current weight to their goal weight, and if they were above their goal weight, they were told to make changes within the context of their approach (see below). After the initial 8 weeks, participants were told to continue self-weighing daily, to report their weight weekly using an automated call-in system, and to evaluate their weekly weight using a color zone system similar to that used in STOP Regain.14 Participants were given personalized charts based on their weight at the end of the initial 8 weeks with the goal of staying in the “green zone”(i.e., not regaining weight). If weight gain was noted (i.e., “red zone”), they were taught to either resume key behavioral strategies or make additional behavior changes consistent with their approach (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of differences between treatment conditions

| Key concepts | Large changes | Small changes |

|---|---|---|

| Overall goal | Lose 5–10 lbs initially to buffer against future weight gain | Make daily changes in energy balance equal to approximately 200 calories/day to prevent weight gain |

| Time frame for behavior change | Periodically—8 weeks per year | Every day throughout the year |

| Diet | Cut 500–1000 calories from daily intake, and then gradually increase intake until maintaining weight, with a continued focus on consuming a low-calorie, low-fat diet | Instructed to make one small change in diet every day (e.g., diet soda instead of regular soda) |

| Physical activity | Instructed to exercise at least 5 days a week, for a total of 250 minutes/week and maintain this level | Given pedometers and instructed to increase steps by 2000 steps per day over baseline levels and maintain this level |

| Self-monitoring | Keep a daily food diary, including calories and fat, and track minutes of physical activity during weight-loss phase. Self-monitor weight daily | Record number of daily steps and check off whether or not a small change in diet was made every day; self-monitor weight daily |

| Strategies to deal with weight gain | Return to calorie-restricted diet, >250 minutes/week of activity, and self-monitoring of intake, activity, and weight | Add one additional change to diet and activity, and continue to use pedometer to track daily steps |

Treatment components that differed for small and large changes intervention

Table 1 presents an overview of the differences between conditions, including goals and prescriptions for each arm. Lessons reflected these different prescriptions. For example, in the SC group the diet lessons focused on small, discrete changes that could be made on a daily basis (e.g., reducing amount of salad dressing or substituting skim milk for milk with 2% milk fat). In contrast, in the LC group, the diet lessons emphasized self-monitoring of calories and fat and adherence to a specific calorie goal. Similarly the SC group was told to increase steps by 2000 steps/day and the LC group was told to get 50 minutes/day of structured activity.

Measures

Demographics

Participants were asked to report their age, gender, education, and weight history.

Weight

Height and weight were measured at baseline, and BMI was calculated to determine eligibility. Weight was measured at 8 and 16 weeks and before each meeting.

Frequency of weighing

Participants reported frequency of self-weighing at each time point. Analyses compared those who weighed at least daily versus those who weighed less frequently. At Weeks 8 and 16, participants reported on a Likert-type scale whether they found weighing daily to be very positive (1) or very negative (8).

Manipulation check questions

At 8 and 16 weeks, participants were asked to indicate (1=never to 8=always) how often they used a variety of strategies to control their weight over the past 8 weeks (e.g., increasing steps, keeping a food diary). They were asked how different their eating and activity had been from their usual behaviors (1=very similar to 8=very different) and how difficult it had been to make these changes (1=very easy to 8=very difficult).

Acceptability/satisfaction

At the end of the program, participants were asked to rate their satisfaction with their approach using a Likert-type rating scale (1=not satisfied to 8=very satisfied). At all time points, participants were asked which approach they thought would be most effective (LC or SC).

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square tests and one-way ANOVAs were used to compare groups at baseline. To assess the effects of treatment on weight, repeated measures ANCOVAs controlling for site were conducted with weight at 0, 8, and 16 weeks. Planned analyses were conducted using ANCOVAs to examine weight change separately from 0 to 8 weeks and 0 to 16 weeks, controlling for baseline weight and site. Intent-to-treat analyses were conducted, with baseline carried forward for missing data. ANOVA was used to compare the two groups on their reported behaviors and satisfaction. Chi-square tests were used to examine expectations of treatment effectiveness at entry and end of the program and the percentage of participants weighing daily. Analyses were conducted in 2008–2009 using general linear modeling in SPSS, version 14.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Fifty-two young adults were randomized to the two groups. On average, participants were aged 25.6±4.7 years with a BMI of 26.7±2.4 kg/m2 and a mean baseline weight of 71.9±8.7 kg; 98% of participants were female and 68.2% were non-Hispanic white. Baseline characteristics did not differ between arms.

Attendance and Retention

On average, participants attended 8.4 of ten sessions; SC participants attended slightly fewer sessions than LC participants (9.1±1.2 for LC and 7.7±3.1 for SC, p=0.05). A total of 86.5% of participants completed the 8-week visit and 84.6% completed the 16-week visit, with no differences between arms.

Distinctness of the Interventions

Adherence to the weighing prescription was excellent in both arms. At baseline, 11.5% of participants reported weighing at least daily, with no differences between groups (p=0.10); after the intervention the majority of participants reported weighing daily (91% in LC and 100% in SC at 8 weeks, p=0.16; and 61% in LC and 90% in SC at 16 weeks, p<0.05). Daily self-weighing was perceived positively in both groups at 8 weeks (8-point scale with 1=very positive and 8=very negative; LC=2.3±1.3 and SC=2.2±1.8, p=0.87) and 16 weeks (LC=3.0±2.5 and SC=2.4±2.1, p=0.40) with no group differences.

In contrast, eating and exercise behaviors differed markedly, in accordance with the behaviors prescribed to each arm. At 8 weeks, the LC group was more likely to report using food diaries and reducing intake by 500–1000 kcal/day, whereas the SC group reported greater use of pedometers, more focus on increasing daily steps, and making one or two small changes to their diet (p’s<0.01). Further, the LC group reported more difficulty making dietary changes and that their eating was more distinct from their usual eating (p’s<0.01).

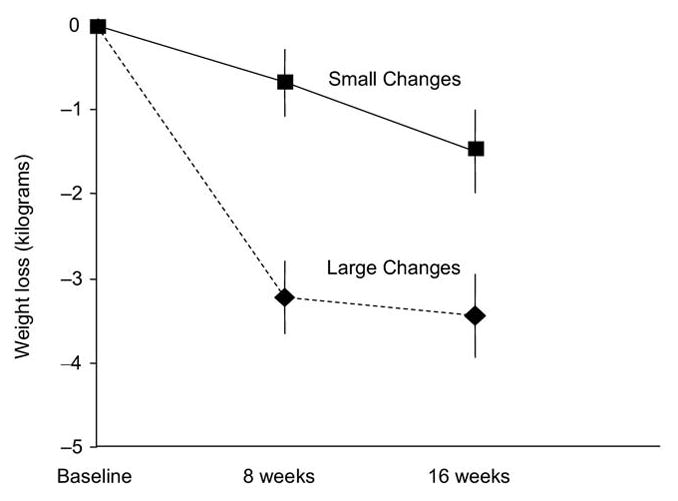

Weight Change

Weight change over the intervention was significantly different between groups (Figure 2). At Week 8, the LC group had lost 3.2±2.5 kg compared to 0.68±1.5 kg in SC (p<0.001); at Week 16, the LC group had an overall weight loss of 3.5±3.1 kg compared to 1.5±1.8 kg in SC (p=0.006).

Figure 2.

Weight changes (kg) for large changes and small changes groups at Week 8 and Week 16

Note: Differences between groups significant at both time points (p<0.01)

Satisfaction and Confidence in Approaches

All participants reported high levels of satisfaction with their approach (1 to 8 with 8=very satisfied; LC= 6.6±1.8; SC=6.3±1.9; p=0.61) and willingness to recommend the approach they were taught to others their age (1 to 8 with 8=very willing; LC=7.1±1.3; SC=7.2± 1.3; p=0.88).

Further, at baseline, participants felt that the LC approach would be more difficult to implement than SC (1 to 8 with 8=very difficult; 5.2±6.0 for LC and 3.3±3.0 for SC, p<0.001). At Week 8, those in the SC group continued to feel that the SC approach would be easier (5.6±2.1 for LC vs 3.3±2.3 for SC, p<0.01). However, those in the LC group had significantly reduced their ratings of the difficulty of the LC approach (4.3±1.6 for LC, p<0.05 compared to baseline).

Moreover, participants had increasing confidence in the approach they were taught. At baseline, >65% of participants in both groups felt that LC would be more effective. However, after the program, only 25% of those in the SC group felt the LC approach would be most effective and 75% now felt the SC approach would be more effective (p<0.01). Likewise, 72% of LC participants reported that the LC approach would be more effective and only 28% felt SC would be better (p<0.01). Findings were comparable at 16 weeks.

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrates the feasibility of using both the Small and Large Changes (SC, LC) approaches within a self-regulation framework for weight-gain prevention in young adults. Attendance and retention in both arms was quite good. Moreover, both groups were willing to self-weigh daily, a key component of a self-regulation approach. The self-report data indicate that the interventions were distinct in their presentation and implementation; participants reported using behavioral approaches during the program that fit with the SC or LC prescription. The marked differences in weight losses over the first 8 weeks clearly attest to differences in the magnitude of changes in energy balance in the two groups and indicate that participants were adhering to their prescriptions.

The study suggests that a self-regulation approach may be a useful framework for preventing weight gain in young adults. At baseline, few participants were weighing daily; however, most were willing to adopt this approach and viewed it positively. Recent studies suggest that daily weighing is related to prevention of weight gain.13,14 Thus, it is of interest and concern that participants in the LC group had decreased their adherence to this strategy by 16 weeks, suggesting that this group may have difficulty maintaining their weight loss in the long term.

Of note was the finding that at the beginning of the study, the majority of participants felt that the LC approach would be more difficult to implement but would be more effective. After treatment, those in the LC group had reduced their difficulty ratings for the LC approach and each group now felt that the approach they had been taught would be the most effective for them. In addition, both groups indicated that they were very satisfied with their approach and would recommend it to others. These findings are particularly encouraging for future studies.

This is the first study to directly compare Small and Large Changes approaches to weight-gain prevention, and the comparison was made in a high-risk group. Although the study is limited by its short duration and small sample, the weight losses from Week 8 to 16 are clearly of interest. The SC group, which was told to persist at making small changes, lost weight at the rate of roughly 0.09 kg (0.2 lb)/week from Week 1 to 8 and from Weeks 9 to 16. In contrast, the LC group initially lost 0.38 kg (0.84 lb)/week during Weeks 1–8, but the rate of weight loss decreased to 0.04 kg (0.09 lb)/week during Weeks 8–16. These weight losses are in keeping with their goal of losing 5–10 pounds initially to serve as a buffer over time. Whether these trajectories would have been maintained over longer follow-up is a critical question.

It is important to note that recruiting men for the present study proved particularly difficult. Given the current sample was 98% women, results cannot be generalized to men and it remains unclear if these approaches would be acceptable to them. Further studies are needed to determine how best to recruit young adults for weight control programs, how to communicate the message of prevention to this audience, and whether Small and Large Changes messages are appropriate across a variety of participant characteristics.

In sum, the present study suggests that the Small and Large Changes approaches may both be acceptable strategies to use within a self-regulation model for weight-gain prevention. A larger trial is needed to determine whether this approach is useful for the prevention of weight gain over a longer period of time and to determine which message—Small or Large Changes—is most effective.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by K23DK083440 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases to Dr. Jessica Gokee LaRose. The authors would like to express their gratitude to Karen E. Erickson, MPH, RD and Molly Grabow, MPH in Chapel Hill and Pamela R. Coward, MEd, RD in Providence, all of whom participated in study coordination and intervention delivery. A special thanks to the participants in the STOP Weight Gain program.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Williamson DF, Kahn HS, Remington PL, Anda RF. The 10-year incidence of overweight and major weight gain in U.S. adults. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(3):665–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Truesdale KP, Stevens J, Lewis CE, Schreiner PJ, Loria CM, Cai J. Changes in risk factors for cardiovascular disease by baseline weight status in young adults who maintain or gain weight over 15 years: the CARDIA study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30(9):1397–407. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hubert HB, Eaker ED, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. Life-style correlates of risk factor change in young adults: an eight-year study of coronary heart disease risk factors in the Framingham offspring. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;125(5):812–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ball K, Brown W, Crawford D. Who does not gain weight? Prevalence and predictors of weight maintenance in young women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(12):1570–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norman JE, Bild D, Lewis CE, Liu K, West DS. The impact of weight change on cardiovascular disease risk factors in young black and white adults: the CARDIA study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(3):369–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manson JE, Skerrett PJ, Willett WC. Obesity as a risk factor for major health outcomes. In: Bray GA, Bouchard C, editors. Handbook of obesity: etiology and pathophysiology. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2004. pp. 813–24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carnethon MR, Loria CM, Hill JO, Sidney S, Savage PJ, Liu K. Risk factors for the metabolic syndrome: the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study, 1985–2001. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(11):2707–15. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.11.2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lloyd-Jones DM, Liu K, Colangelo LA, et al. Consistently stable or decreased body mass index in young adulthood and longitudinal changes in metabolic syndrome components: the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Circulation. 2007;115(8):1004–11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.648642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeffery R, French S. Preventing weight gain in adults: the pound of prevention study. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(5):747–51. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.5.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine MD, Klem ML, Kalarchian MA, et al. Weight gain prevention among women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(5):1267–77. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hivert MF, Langlois MF, Berard P, Cuerrier JP, Carpentier AC. Prevention of weight gain in young adults through a seminar-based intervention program. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(8):1262–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eiben G, Lissner L. Health Hunters—an intervention to prevent overweight and obesity in young high-risk women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30(4):691–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linde JA, Jeffery RW, French SA, Pronk NP, Boyle RG. Self-weighing in weight gain prevention and weight loss trials. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30(3):210–6. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Fava JL. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1563–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Reed GW, Peters JC. Obesity and the environment: where do we go from here? Science. 2003;299:853–55. doi: 10.1126/science.1079857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodearmel SJ, Wyatt HR, Stroebele N, Smith SM, Ogden LG, Hill JO. Small changes in dietary sugar and physical activity as an approach to preventing excessive weight gain: the America on the Move family study. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e869–79. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodearmel SJ, Wyatt HR, Barry MJ, et al. A family-based approach to preventing excessive weight gain. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(8):1392–401. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Field AE, Wing RR, Manson JE, Spiegelman DL, Willett WC. Relationship of a large weight loss to long-term weight change among young and middle-aged U.S. women Int J Obes. 2001;25:1113–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuller LH, Simkin-Silverman LR, Wing RR, Meilahn EN, Ives DG. Women’s healthy lifestyle project: a randomized clinical trial: results at 54 months. Circulation. 2001;103(1):32–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simkin-Silverman LR, Wing RR, Boraz MA, Kuller LH. Lifestyle intervention can prevent weight gain during menopause: results from a 5-year randomized clinical trial. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(3):212–20. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2603_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanfer FH, Goldstein AP. Helping people change. New York: Pergamon Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]