Abstract

Pontine structures are critical for the generation of rapid eye movement sleep but there are only a few reports of the effects of focal pontine lesions on sleep patterns in humans. We report the case of an 81-year-old man admitted for the acute onset of disordered speech and motor deficit in the upper right arm who developed hypersomnia within a week. A 24-hour polysomnographic study revealed a very severe disruption of both circadian rhythm and sleep organisation, and a brain MRI documented an ischaemic lesion of the anterior left paramedian portion of the pons. Our observation suggests that even small, paramedian pontine ischaemic lesions can acutely induce a very severe sleep disorder.

BACKGROUND

A hypersomnolent state is a hallmark of paramedian thalamic strokes in which sleep needs are markedly increased and the patient’s ability to maintain attention is reduced.1–3 Sleep studies have shown an increased sleep duration with predominance of superficial sleep stages, increased sleep fragmentation and decreased sleep spindles.2–4 Hypersomnia has been considered the result of the disruption of thalamic sleep-generating and arousal-maintaining mechanisms.2 Several electrophysiological data suggest that pontine structures are also critical for the generation of sleep phenomena, especially network organisation in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.5 Pontogeniculo-occipital waves generated or propagated in the ponto-mesencephalic tegmentum are a feature of human REM sleep and are proposed to mediate a wide variety of sleep-related neural processes.6 Yet, only a few reports of the effects of focal brainstem lesions on sleep patterns in humans are available in the literature.7

CASE PRESENTATION

An 81-year-old man with a hypertension and diabetes mellitus was admitted to our hospital for the acute onset of neurological signs. He was currently being treated with ramipril 5 mg once daily, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg once daily, aspirin 100 mg once daily, glibenclamide/metformin 400/2.5 mg twice daily and omeprazole 20 mg once daily, and his clinical history was totally unremarkable.

INVESTIGATIONS

On admission, blood pressure was 140/70 mmHg, pulse rate was regular at 86 bpm, body temperature was 36.8°C and oxygen saturation was 94%. The neurological examination revealed disordered speech and a motor deficit in the upper right arm. Acutely, he did not show any vigilance impairment: the patient was fully awake and well-oriented; cranial nerves and sensory examination were normal. Other physical examinations were unremarkable. Laboratory tests revealed a normal blood cell count; serum electrolytes levels were within the normal range. Fasting serum glucose was 155 mg/dl, haemoglobin A1c was 6.9%; serum creatinine was 1.4 mg/dl with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 44 ml/min (Cockroft-Gault formula).

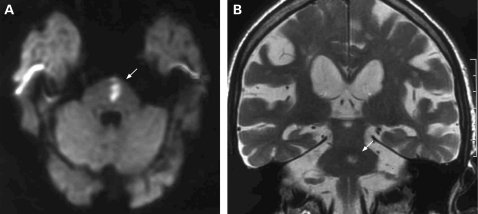

A brain CT scan performed 4–6 hours after symptoms onset showed no evidence of acute haemorrhage, but rather non-specific white-matter vascular lesions. A brain MRI study, performed within 72 hours of the onset of symptoms, revealed an area of hyperintense signal in long TR and diffusion-weighted image (DWI) sequences, located in the anterior, left paramedian portion of the pons (fig 1), without contrast enhancement. This finding was consistent with a subacute ischaemic lesion.

Figure 1.

Brain MRI performed 72 hours after the onset of symptoms. (A) Diffusion-weighted images (DWI) showing the area of acute cytotoxic oedema (arrow) in the left paramedian portion of the pons. (B) T2-weighted images, coronal plan, showing the same lesion (arrow).

In the following week, the patient progressively developed a hypersomnolent state characterised by repeated sudden episodes of daytime sleep accompanied by severe nocturnal sleep fragmentation.

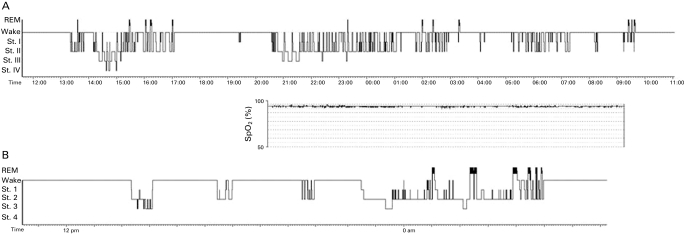

A 24-hours polysomnographic (PSG) study was performed following adaptation and the results are shown in fig 2. No central or obstructive phases of apnoea or other respiratory abnormalities were detected. The patient did not show any significant nocturnal desaturation. PSG revealed a very severe disruption of both circadian rhythm and sleep organisation. The study revealed an irregular succession of episodes of sleep and wakefulness over the 24 hours. Sleep appeared superficial and fragmented with repeated awakenings; there was a very low prevalence of slow wave sleep (stages 3 and 4 non-rapid eye movement (NREM)) and an almost total absence of REM sleep.

Figure 2.

(A) Twenty-four hours sleep hypnogram, recorded 10 days after the onset of symptoms. St. I, II, III and IV = stage I, II, III and IV non-rapid eye movement. (B) Hypnogram obtained 3 months later. An episode of nocturnal sleep is evident, with increased duration of rapid eye movement sleep. Daytime sleep duration appears to be decreased, but three episodes of sleep can still be observed during the daytime. No further recording of sleep could be performed during follow-up.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

By day 10, the patient was in stable clinical conditions and was discharged to a rehabilitation facility. One month later, a residual motor deficit was still present but speech had greatly improved; hypersomnia was also still present. While hypersomnia did recover to a large extent at 3 months after the stroke, sleep architecture remained abnormal.

DISCUSSION

The most relevant finding in this patient with a small paramedian pontine ischaemic lesion was the simultaneous presence of a disruption of the circadian rhythm (with nocturnal insomnia and a daytime hypersomnolent state) and a severe alteration of the NREM-REM sleep mechanisms. There have been rare reports of REM sleep disorders in association with lesions within or near the pontine tegmentum. Recently, Landau et al described a decreased percentage of REM sleep in four out of eight patients with isolated brainstem lesions.8 A parasomnia characterised by intermittent loss of electromyographic atonia during REM sleep with elaborate and violent behaviour has been reported with unilateral pontine vascular lesions.9,10 The current view on REM sleep generation indicate that the REM-on region is medial to the locus ceruleus at the lower/mid level of the pons. In analogy to animal models,11 it is possible that in our case a lesion to the precoeruleus region was implicated in the REM sleep disorder. To our knowledge, there has been only a single report of sleep-waking cycle and NREM sleep alterations associated with pontine ischaemia. Indeed, Tamura et al observed a clinical syndrome characterised by alteration of the circadian rhythm, absence of REM phases and severely disorganised NREM phases. However, the patients in this series presented extensive pontine vascular lesions involving the pontine tegmentum.12

In conclusion, our observation suggests that a relatively small, paramedian pontine ischaemic lesion can acutely induce a very severe sleep disorder. This can present clinically as an excessive daytime sleepiness affecting not only REM but also NREM phases. Such impairment in sleep regulation may result in a global disruption of the circadian sleep-waking rhythm.

Although no medications were used in our case, some of the alterations described might be amenable to pharmacological treatment with modafinil, tricyclic antidepressants and even melatonin.

LEARNING POINTS

There have been rare reports of sleep disorders in association with extensive lesions within or near the pontine tegmentum.

Even small paramedian pontine ischaemic lesions can acutely induce sleep disorders with a very severe disruption of both circadian rhythm and sleep organisation.

Hypersomnolent state tends to recover within 3 months, but sleep architecture appears to remain abnormal more persistently.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lovblad KO, Bassetti C, Mathis J, et al. MRI of paramedian thalamic stroke with sleep disturbance. Neuroradiology 1997; 39: 693–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassetti CL, Mathis J, Gugger M, et al. Hypersomnia following paramedian thalamic stroke: a report of 12 patients. Ann Neurol 1996; 39: 471–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermann DM, Siccoli M, Brigger P, et al. Evolution of neurological, neuropsychological and sleep-wake disturbances after paramedian thalamic stroke. Stroke 2008; 39: 62–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santamaria J, Pujol M, Orteu N, et al. Unilateral thalamic stroke does not ddecrease ipsilateral sleep spindles. Sleep 2000; 23: 333–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amzica F, Steriade M. Progressive cortical synchronizatrion of ponto-geniculo.occipital potentials during rapid eye movement sleep. Neuroscience 1996; 72: 209–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim AS, Lozano AM, Moro E, et al. Characterization of REM-sleep associated ponto-geniculo-occipital waves in the human pons. Sleep 2008; 30: 823–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Autret A, Lucas B, Mondon K, et al. Sleep and brain lesions: a critical review of the literature and additional new cases. Neurophysiol Clin 2001; 31: 356–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landau ME, Maldonado JY, Jabbari B. The effects of isolated brainstem lesions on human REM sleep. Sleep Med 2005; 6: 37–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura K, Tachibana N, Kohymana J, et al. A discrete pontine ischemic lesion could cause REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology 2000; 55: 894–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xi Z, Luning W. REM sleep behavior disorder in a patient with pontine stroke. Sleep Med 2009; 10: 143–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel J. The stuff dreams are made of: anatomical substrates of REM sleep. Nat Neurosci 2006; 9: 721–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamura K, Karacan I, Williams RL, et al. Disturbances of the sleep-waking cycle in patients with vascular brain stem lesions. Clin Electroencephalogr 1983; 14: 35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]