Abstract

A 54-year-old man with a past history of splenectomy some 20 years previously presented with a hepatic mass. Subsequent histopathology revealed that the mass was due to intrahepatic splenosis. The presentation of this case is discussed together with a literature review of splenosis.

BACKGROUND

Splenosis represents the heterotopic autotransplantation of splenic tissue after either splenic trauma or surgery, which is an uncommon finding in clinical practice. Here we report a case of a patient with solitary intrahepatic splenosis, a rare condition that may be misdiagnosed as hepatic hepatoma. However, its frequency is likely underestimated because most splenic implants are asymptomatic and are only found either incidentally or after symptomatic complications.

Splenosis therefore is an important differential diagnosis of abdominal masses in patients with the history of splenic surgery or trauma.

CASE PRESENTATION

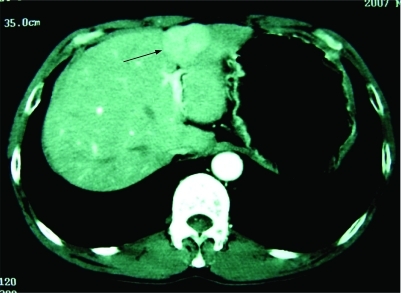

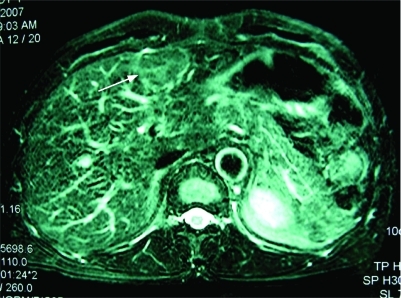

A 54-year-old man was admitted to our hospital because of a hepatic mass. His medical history was unremarkable except for splenectomy and simultaneous blood transfusion following a vehicle accident about 20 years ago. His family history was also non-specific. In May 2007, during a routine surveillance programme, ultrasonography revealed a 40 mm isoechoic lesion in his liver, with Doppler evidence of arterial hypervascularisation, located in the left hepatic lobe near the capsule. Computed tomography (CT) confirmed one well circumscribed focal bulging mass in the left lobe of the liver, with strong and slightly inhomogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase (fig 1) and diminished enhancement in the portal venous phase. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed the mass to be slightly hyperintense on T2 weighted images (fig 2) and relative hypointense on T1 weighted images. No central scar was identified within the mass. On admission, the patient denied abdominal pain, fatigue, nausea, fever, or weight loss. Physical examination revealed no hepatomegaly and no signs of liver decompensation. The results of a complete blood count and the serum concentrations of aminotransferases were all within the normal range, as were the values of α-fetoprotein(2.6 ng/ml), carcinoembryonic antigen (1.98 ng/ml) and carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (9.0 U/ml). The serum biomarkers of hepatitis B virus infection were negative and the Child–Pugh grade was A (score 5). Because of the uncertainty of the diagnosis of the mass, the patient underwent a partial resection of the liver.

Figure 1. Computed tomography showing a mass in the left lobe of the liver (arrowheads).

Computed tomography of the abdomen shows one focal bulging mass in the left lobe of the liver, with early inhomogeneous enhancement during the arterial phase.

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging showing the mass to be slightly hyperintense (arrowheads).

T2 weighted fast spin echo MR sequence shows the mass to be slightly hyperintense on T2 weighted images.

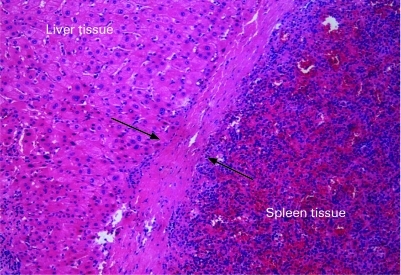

During surgery, the mass was noted to be in the left lobe near the phrenic surface and no other similar masses were found in the abdominal cavity. The splenosis mass was completely embedded in the liver tissue. The section of the mass specimen appeared dark red, with a clear border surrounded by a capsule. Histopathology of the specimen demonstrated the intrahepatic splenosis (fig 3). The pathologic examination revealed sinusoidal structures and lymphoid follicular aggregates distributed around the central arterioles, denoting red and white pulp, respectively, which proved that the lesion consisted of healthy splenic tissue. The patient made a quick recovery after surgery and he was in good condition during the close follow-up of 6 successive months.

Figure 3. Histology showing splenosis.

A capsule separates the liver and spleen parenchymas (arrowheads). On the left is liver tissue, on the right spleen with lymphoid follicular aggregates and sinusoidal structures. A capsule separates the two parenchymas. Haematoxylin and eosin ×200.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

By standard imaging techniques, such as ultrasonography, CT or MRI, the radiological characteristics of the intrahepatic splenosis are usually indistinguishable from liver tumours.

Hepatic splenosis may mimic hepatic adenoma, focal nodular hyperplasia, hepatocellular carcinoma, or metastatic liver neoplasms.

Particularly in patients with liver cirrhosis, aberrant α-fetoprotein values and a background of hepatitis virus infection, it is more difficult to make a correct differential diagnosis of hepatic splenosis from hepatocellular carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

The term splenosis, first used in the medical literature in 1939, refers to the autotransplantation and implantation of splenic tissue in a heterotopic location after splenic trauma or surgery.1 Splenosis may form when viable splenic cells and pulp spill and implant.2 Although splenosis can occur anywhere, the implants are found most commonly in the peritoneal cavity, such as mesentery, omentum and other peritoneal surfaces.3 If splenic rupture is associated with a diaphragmatic tear, the implants may seed the pleural cavity or pericardium, which causes intrathoracic splenosis.4 Splenosis implants are generally numerous, supplied by arteries from the surrounding tissue rather than a hilar artery. In addition, splenosis implants usually have no particular shape and have neither hilus nor normal capsule. However, the case we reported here demonstrated an intrahepatic splenosis with clear fibrous capsule.

Splenosis should be distinguished from accessory spleens, which represent failure of the splenic anlagen to fuse during embryogenesis and can be found in 10–40% of patients at autopsy and rarely exceed 1.5 cm in diameter. Accessory spleens are usually solitary, rarely exceed six in number, and are most commonly located on the left side of the dorsal mesogastrium in the region of the splenopancreatic or gastrosplenic ligaments. Histologically, accessory spleens resemble the normal spleen which contain a hilus, a capsule, parenchyma with normal pulp and always receive blood supply from branches of the splenic artery.5

Review of the relevant literature reveals splenosis of viscera organs is rarely reported. Intrahepatic splenosis is the heterotopic autotransplantation of splenic tissue in the liver and fewer than 20 cases of intrahepatic splenosis have been reported until now. Isolated hepatic splenosis is more rarely reported. The pathogenesis of intrahepatic splenosis is still unclear. Except for the direct seeding power of viable splenic cells and pulp into the liver during splenic trauma, intrahepatic splenosis may also result from a rare condition of ectopic erythropoiesis in the liver. Based on the susceptibility of the splenic erythropoiesis response to hypoxia and the inevitability of hypoxia caused by aging or pathological changes, the two events–the migration of the erythrocytic progenitor cells via the portal vein following traumatic splenic rupture, and the induction of erythropoiesis by local hypoxia of liver–might cause the occurrence of the intrahepatic splenosis.6

Although splenosis is usually asymptomatic, as in the patient reported here, complications of splenosis have been reported. These complications include abdominal and flank pain,7 spontaneous rupture leading to peritoneal haemorrhage,8 erosion through the bowel wall resulting in gastrointestinal haemorrhage,9 relapse of haematologic diseases by residual splenosis,10 mass effect upon normal organs and bowel obstruction secondary to adhesive bands of splenic implants, or associated with infarction of the implants.11 Since splenosis implants are usually asymptomatic, they are mostly discovered accidentally during imaging procedures. Herein the imaging characteristics of these lesions are summarised as follows.

Ultrasonography usually reveals hepatic splenosis to be a hypoechoic or isoechoic lesion, with Doppler evidence of arterial hypervascularisation.12 Splenosis is usually hypodense compared with the surrounding liver parenchyma on unenhanced helical CT examination. On contrast enhanced CT scanning, hepatic splenosis usually shows strong and slightly inhomogeneous enhancement during the arterial phase, with diminished enhancement in the portal venous phase, becoming hypodense compared with the surrounding parenchyma.13 Splenosis is mostly hypointense on images obtained with the T1 weighted gradient echo MR sequence and hyperintense on images obtained with the T2 weighted fast spin echo MR sequence. Heterogeneous or homogeneous enhancement of the lesion is also present during the arterial phase of the dynamic gradient echo MR sequence, with diminished enhancement in the portal phase.14 On both CT and MRI, intrahepatic splenosis lesions usually appear to indent the surface of the liver. By standard imaging techniques, such as ultrasonography, CT, or MRI, the radiological characteristics of the intrahepatic splenosis are usually indistinguishable from liver tumours. Hepatic splenosis may mimic hepatic adenoma, focal nodular hyperplasia, hepatocellular carcinoma, or metastatic liver neoplasms.15–18 Particularly in patients with liver cirrhosis, aberrant α-fetoprotein level and background of hepatitis virus infection, it is more difficult to make a correct differential diagnosis of hepatic splenosis from hepatocellular carcinoma.19

The confusion between intrahepatic splenosis and other hepatomas often leads to unnecessary biopsy or surgical exploration. Sometimes hepatic splenosis may be pointlessly treated with chemotherapy or chemoembolisation.20 Because splenosis is not a pathologic and aggressive process and is usually innocuous, it should not be electively removed in general. Furthermore, it appears to be immunologically functional, probably representing an attempt by the body to regain splenic activity. It is necessary to develop more specific methods to diagnose intrahepatic splenosis. So far radionuclide scintigraphy specific for functioning splenic tissue is considered the method of choice to differentiate splenosis from other masses. Technetium-99m (99mTc) sulfur colloid scintigraphy is able to reveal a 2 cm or larger nodule of splenic tissue. The normal liver takes up most of the sulfur colloid whereas the spleen receives only 10% of this radiotracer.21 Small splenosis nodules in the upper abdomen may be obscured by normal hepatic uptake of the sulfur colloid. However, because functioning splenic tissue will trap approximately 90% of damaged erythrocytes, technetium-99m (99mTc) labelled heat denatured erythrocytes are reported to be more sensitive than sulfur colloid in the identification of splenosis, demonstrating an increased uptake of the radioactive isotope in ectopic splenic tissue and reduced uptake of 99mTc in otherwise normal liver tissue.22 MRI contrast agents composed of super-paramagnetic iron oxide particles, that show a tissue specific biodistribution to phagocytic reticuloendothelial cells of liver and spleen after intravenous injection, have also been used in patients with splenosis.23 These agents produce local inhomogeneities in the magnetic field causing rapid dephasing of transverse magnetisation, resulting in a loss of signal intensities on MRI of both ectopic splenic tissue and normal spleen.

Once considered a rare condition, splenosis is now estimated to occur in up to 67% of patients with splenic rupture.24 Splenosis therefore is an important differential diagnosis of abdominal masses in patients with the history of splenic surgery or trauma. So, awareness of this condition, combined with a history of splenic trauma or surgery, may prevent both pointless surgical interventions of splenosis and resultant asplenia. If splenosis is suspected, either clinically or radiographically, radionuclide scintigraphy can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

LEARNING POINTS

Two events–the migration of the erythrocytic progenitor cells via the portal vein following traumatic splenic rupture, and the induction of erythropoiesis by local hypoxia of the liver–might cause the occurrence of the intrahepatic splenosis.

The high incidence of pointless surgical interventions in patients with splenosis may remind us of the importance and necessity to be aware of splenosis during the differential diagnosis of abdominal masses in patients with a history of splenic surgery or trauma.

If splenosis is suspected, either clinically or radiographically, radionuclide scintigraphy can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Buchbinder JH, Lipkoff CJ. Splenosis: Multiple peritoneal splenic implants following abdominal injury. Surgery 1939; 6: 927–34 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brewster DC. Splenosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg 1973; 126: 14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turkmen C, Yormaz E. Incidental detection of multiple abdominopelvic splenosis sites during Tc-99m HMPAO-labeled leukocyte scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med 2006; 31: 572–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amy HH, Kitt S. Case 93: Thoracic Splenosis. Radiology 2006; 239: 293–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiand G, Mangold G. Accessory spleen in the pancreatic tail – a neglected entity? A contribution to embryology, topography and pathology of ectopic splenic tissue. Chirurg 2003; 74: 1170–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwok CM, Chen YT, Lin HT, et al. Portal vein entrance of splenic erythrocytic progenitor cells and local hypoxia of liver, two events cause intrahepatic splenosis. Med Hypotheses 2006; 67: 1330–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heider J, Winter P, Kreft B. Symptomatic heterotopic splenic tissue in the adrenal gland area. Aktuelle Radiol 1998; 8: 135–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuckow P. Spontaneous rupture: a new complication of splenosis. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1991; 36: 186–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basile RM, Morales JM, Zupanec R. Splenosis. A cause of massive gastrointesti- nal hemorrhage. Arch Surg 1989; 124: 1087–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gigot JF, Jamar F, Ferrant A, et al. Inadequate detection of accessory spleens and splenosis with laparoscopic splenectomy. A shortcoming of the laparoscopic approach in hematologic diseases. Surg Endosc 1998; 12: 101–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato M, Motohiro T, Seto S, et al. A case of splenosis after laparoscopic splenectomy. Pediatr Surg Int 2007; 23: 1019–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferraioli G, Di Sarno A, Coppola C, et al. Contrast-enhanced low-mechanical–index ultrasonography in hepatic splenosis. J Ultrasound Med 2006; 25: 133–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horger M, Eschmann SM, Lengerke C, et al. Improved detection of splenosis in patients with haematological disorders: the role of combined transmission emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2003; 30: 316–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brancatelli G, Vilgrain V, Zappa M, et al. Case 80: Splenosis. Radiology 2005; 234: 728–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim KA, Park CM, Kim CH, et al. An interesting hepatic mass:splenosis mimicking a hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur Radiol 2003; 13: 2713–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gruen DR, Gollub MJ. Intrahepatic splenosis mimicking hepatic adenoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997; 168: 725–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foroudi F, Ahern V, Peduto A. Splenosis mimicking metastases from breast carcinoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1999; 11: 190–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gamulin A, Oberholzer J, Rubbia-Brandt L, et al. An unusual, presumably hepatic mass. Lancet 2002; 360: 2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Costanzo GG, Picciotto FP, Marsilia GM, et al. Hepatic splenosis misinterpreted as hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients referred for liver transplantation: report of two cases. Liver Transpl 2004; 10: 706–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JB, Ryu KW, Song TJ, et al. Hepatic splenosis diagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma: report of a case. Surg Today 2002; 32: 180–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yammine JN, Yatim A, Barbari A. Radionuclide imaging in thoracic splenosis and a review of the literature. Clin Nucl Med 2003; 28: 121–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagan I, Hopkins R, Lyburn I. Superior demonstration of splenosis by heat-denatured Tc-99m red blood cell scintigraphy compared with Tc-99m sulfur colloid scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med 2006; 31: 463–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berman AJ, Zahalsky MP, Okon SA, et al. Distinguishing splenosis from renal masses using ferumoxide-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Urology 2003; 62: 748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hospital Case records of the Massachusetts General. Weekly clinicopathological exercises: case 29–1995. A 65-year old man with mediastenal Hodgkin’s disease and a pelvic mass. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 784–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]