Abstract

The present report concerns an unusual case of extranodal Rosai–Dorfman disease involving the epicardium, mesenterium, pleural cavity and lung. All involved lesions showed characteristics of S100-positive histiocytes exhibiting emperipolesis. The patient was a 51-year-old woman with a 2-year evolution of chest distress, dyspnoea and oedema. Pathological examination indicated that heart failure, which resulted from constrictive pericarditis, led to the fatal outcome of this case. Interference from severe hydropericardium prevented timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Therefore it is recommend that, despite being a rare condition, pericardium-involved Rosai–Dorfman disease should be taken into consideration in differential diagnoses, especially in cases of severe hydropericardium.

BACKGROUND

Although there have been hundreds of case reports of Rosai–Dorfman disease, an idiopathic and benign histiocytic proliferative disorder, this case was confusing from the initial diagnosis by clinical residents to the final pathological examination by us. The clinical diagnosis, even with the assistance of positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, varied from tuberculosis to connective tissue disease and lymphoma, and this variation prevented the appropriate treatment from being administered. Moreover, in the course of the autopsy examination we assumed erroneously that the condition was tuberculosis or lymphoma because of the pulmonary miliary foci, renal and splenic necrosis lesions and mass in the mesentery, until a diagnosis of Rosai–Dorfman disease was made by morphology and immunochemistry. Ironically, despite the clinical presentations of the patient such as chest distress, dyspnoea, increasing oedema and autopsy findings such as the nutmeg liver indicating heart failure, no significant alteration of the myocardial cells, coronary arteries and valves of the heart were observed macroscopically or microscopically. Heart failure, the fatal consequence of this rare case, might have resulted from Rosai–Dorfman disease-affected pericardium adhering and encapsidating the heart (constrictive pericarditis).

Therefore we recommend clinical residents be aware of the incidence of atypical Rosai–Dorfman disease, which could be involved with multiple systems without massive lymphadenopathy and result in a poor prognosis rather than the benign disorder usually presented.

CASE PRESENTATION

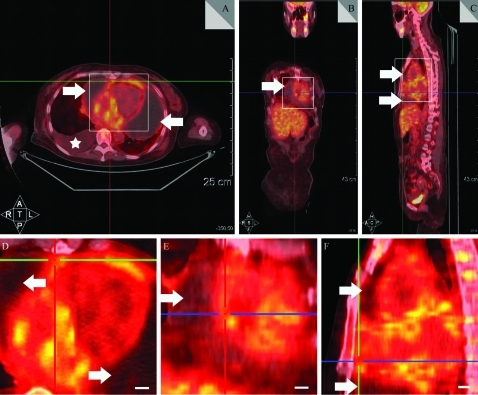

A 51-year-old woman was admitted to hospital with a 2-year history of chest distress, dyspnoea, and oedema of both legs and eyelids. No such signs and symptoms were found in any other lineal relation in her family. On admission, severe hydropericardium and hydrothorax, and thickened pleura were confirmed by physical examination, PET/CT (fig 1) and B-ultrasonography. Her white cell count was 13.2×109/litre (normal range 4–10×109/litre), platelet count was 63×109/litre (normal range 100–300×109/litre), serum Na+ was 123 mmol/litre (normal range 135–147 mmol/litre) and Cl− was 88 mmol/litre (normal range 95–105 mmol/litre). Urea Na+ was 24 mmol/litre (normal range 40–200 mmol/litre) and Cl− was 27 mmol/litre (normal range 110–250 mmol/litre). Total serum bilirubin was 68 μmol/litre (normal range 2–24 μmol/litre). Total serum protein was 47 g/litre (normal range 64–83 g/litre). Consecutive drainage, diuresis, appropriate anti-infection treatment and corresponding nutritional support treatment were given. Her symptoms deteriorated with aggravation of chest distress, dyspnoea and generalised oedema. Blood pressure and heart rate descend to 0 gradually over 2 days, and the patient died after a 2-year evolution of the condition.

Figure 1.

Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT presentations of the hydropericardium and hydrothorax. A. Horizontal plane. B. Coronal plane. C. Sagittal plane. D. Amplified focus of square region in (A). E. Amplified focus of square region in (B). F. Amplified focus of square region in (C). Arrows indicate significant effusion in the pericardial sac and asterisks indicated significant effusion in the right thoracic cavity. Scale bar 1 cm.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Tuberculosis, connective tissue disease and lymphoma

TREATMENT

Consecutive drainage, diuresis, appropriate anti-infection treatment and corresponding nutrition support treatment were given.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient’s blood pressure and heart rate descended to 0 gradually over 2 days, and the patient died after a 2-year evolution of the condition.

Autopsy was carried out on the second day after death. Skin cyanosis had taken place on the lips and nail beds. The degree of anasarca was serious, demonstrating high-tension skin on eyelids, face, all fingers and toes, and pitting oedema on the hands, feet, upper and lower limbs.

Under the anterior chest wall, effusions with rich protein in the pericardial sac and thoracic cavity had reached nearly 1000 ml and 1200 ml, respectively. The pericardium had formed scar tissue on the cardiac surface, causing the external surface of the cardium to become incrassate, rough and stiff, encapsulating the cardium like a bread crust (fig 2A). The cut surface of five lung lobes were all scattered with small white miliary foci (1 mm), mainly along the thickened pleural cavity, which resembled miliary pulmonary tuberculosis from the distribution and shape of miliary foci (fig 2B). There was a 15×10×5 cm3 volume, 284 g weight mass on the radicle of the mesentery, presenting as a well defined yellow–grey capsule with an uneven surface, hard texture and heterogeneous yellow–grey cut surface, without significant blood vessels or necrotic foci (fig 2C,D).

Figure 2.

Autopsy findings. A. Constrictive pericarditis; the right section is scar tissue cut from the very front of the heart. B. Numerous small white miliary foci (1 mm) scattering on the cut surface of lung lobes and thickened pleural cavity. C. The mass in situ on the radicle of the mesentery. D. The mass in the mesentery.

Other lesions included one 6 cm obstructive embolus in the splenic artery (fig 3A) and several mural thrombi in the ascending aorta (fig 3B). A splenic anaemia infarction formed, occupying more than 60% of the area of the cut surface (fig 3C). There was one anaemia infarction focus in the right kidney and several fused infarction foci in the left kidney. The whole liver presented as typical nutmeg liver (fig 3D).

Figure 3.

Other autopsy findings. A. The obstructive embolus in the splenic artery. B. Arrows indicate several mural thrombi in the ascending aorta. C. Splenic anaemia infarction. D. Nutmeg liver.

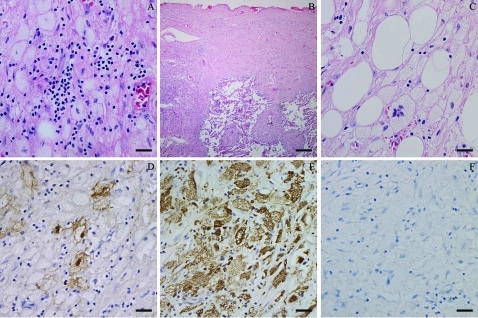

The epicardium was remarkably thickened and consisted of four layers. First, a cell layer, which mainly included large histiocytic cells with lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils adjacent to the normal myocardial cells; second, a young granulation tissue layer, which was composed of proliferating fibrous tissue and new capillaries; third, a scar tissue layer; and fourth protein exudated on the most external layer. These histiocytes possessed a distinct cell membrane, abundant, pale or vacuolated cytoplasm, flat, reniform nuclei with smooth nuclear membrane, fine chromatin and distinct nucleoli (fig 4A). Some of them were multinucleate, engulfing lymphocytes and plasma cells (emperipolesis). These histiocytes were strongly positive for S100 and CD68 protein, but negative for CD1a on immunohistochemistry (fig 4D–F). The manifestation of lesions in the pleural cavity under microscopy was similar to that in the epicardium. Moreover, individual lesions spreading along the lobular arteries of the lungs were either microscopic or small, visible foci of white consolidation scattered through the lung parenchyma (fig 4B), which could be detected as small white miliary foci on the cut surface of the five lung lobes with the naked eye. These histiocytes in the visceral pleural cavity and along the lung arteries were also positive for S100 and CD68, but negative for CD1a. Sections from several different parts of the mass on the radicle of the mesentery showed almost the same characteristics of morphology and immunohistochemistry as the lesion in the epicardium, despite disorganised layers between the large histiocytes and granulation tissue (fig 4C).

Figure 4.

Lesions related to Rosai–Dorfman disease. A. Lesions of the pericardium. B. Lesions of the pleural cavity and lung. C. Lesions of the mass on the radicle of the mesentery. D. S100 positive. E. CD68 positive. F. CD1a negative. Scale bar 50 μm, except for (B) 400 μm.

Therefore, a diagnosis of Rosai–Dorfman disease (RDD) involving the epicardium, pleural cavity, lung and mesentery was made. Other results of the pathological examination are detailed in the Discussion.

DISCUSSION

Destombes/Rosai–Dorfman disease (RDD) or sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (SHML) is a rare disease first described by Destombes1 in 1965, and recognised and specified as a new clinicopathological entity by Rosai and Dorfman in 19692 and 1972.3 RDD in its classic form is an idiopathic, benign histiocytic proliferative disorder characterised by massive lymphadenopathy. The clinical sign is chronic, painless, massive cervical lymphadenopathy. Extranodal RDD has been reported in approximately 40% of cases, either alone or in association with lymphadenopathy; the most common sites of extranodal involvement are the skin, upper respiratory tract and bone. RDD can also occur in a variety of other sites, including the genitourinary system, lower respiratory tract, oral cavity and soft tissues.4

A review of the literature reveals there have been few specific reports concerning extranodal involvement of the epicardium in RDD; one involving the heart has been reported in English5 and one involving the heart in the German literature.6 There have also been no previous reports on mesenterium involvement in RDD. Four reports exist on pleural cavity involvement in RDD.7–10 Involvement of the lower respiratory tract by RDD is relatively rare and comprises 3% of extranodal RDD cases.11 Involvement of the kidney, lower respiratory tract, or liver was found to be a poor prognostic sign; prognosis has been found to correlate with the number of nodal groups and with the number of extranodal systems involved in RDD.4

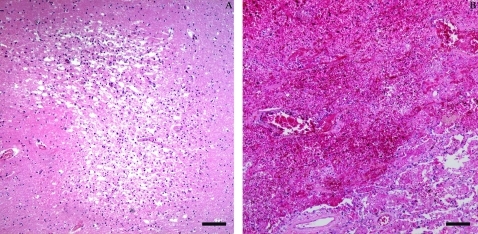

There were two main complications from haemodynamic disorders found on pathological examination of this case, correlating with each other: one was thrombosis, systemic thromboembolism and infarction, the other was oedema. There were several mural thrombi in the ascending aorta, and one 6 cm obstructive embolus in the splenic artery, causing splenic and renal anaemia infarction. Besides splenic and renal infarction, one infarct focus was found in the basal ganglia under microscopy (fig 5A) and a pulmonary infarction (fig 5B) in the lower right lobe indicated systemic thromboembolism. Oedema had two different forms, anasarca, a severe and generalised oedema with profound subcutaneous tissue swelling, involving the eyelids (periorbital oedema), face, hands, feet, upper, lower limbs (pitting oedema) and effusion in the body cavities, pericardial sac (hydropericardium) and thoracic cavity (hydrothorax).

Figure 5.

A. The infarction lesion in the brain. B. The infarction lesion in the lung. Scale bar 200 μm.

The interference from severe hydropericardium prevented timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment for constrictive pericarditis resulting from an inflammation response to Rosai–Dorfman disease, originally an idiopathic, benign histiocytic proliferative disorder characterised by massive lymphadenopathy that resulted in a fatal outcome in this case. Clinical methods including electrocardiogram, PET/CT and B-ultrasonography could not detect significant abnormality of the heart, and neither could pathological examination; signs and presentations of this case indicated an obvious heart failure, which can be caused and furthered by hydropericardium and constrictive pericarditis, the latter being a crucial factor. In summary, we recommend that, despite being rare, pericardium-involved Rosai–Dorfman disease should be taken into consideration in differential diagnoses, especially in cases of severe hydropericardium.

LEARNING POINTS

There can be extranodal involvement of epicardium in Rosai–Dorfman disease.

Heart failure should be taken into consideration when symptoms of chest distress, dyspnoea and oedema emerge.

Hydropericardium and constrictive pericarditis can exist simultaneously and both are capable of causing and furthering heart failure.

Acknowledgments

The family of the patient gave their consent for the medical records to be reviewed for research and publication. We thank them for their support.

The funding source had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Destombes P. Adenitis with lipid excess, in children or young adults, seen in the Antilles and in Mali. (4 cases) [in French]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales 1965; 58: 1169–75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. A newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol 1969; 87: 63–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a pseudolymphomatous benign disorder. Analysis of 34 cases. Cancer 1972; 30: 1174–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai–Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol 1990; 7: 19–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchino JJ, Byrd RP, Kmetz DR. Disseminated sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: its pathologic aspects. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1982; 106: 13–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheffel H, Vogt P, Alkadhi H. Cardiac manifestation of Rosai–Dorfman Disease [in German]. Herz 2006; 31: 715–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zagdańska J, Krakówka P, Polowiec Z. Sinus histiocytosis with generalized lymphadenopathy - Rosai–Dorfman disease [in Polish]. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 1992; 60:55–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petschner F, Walker UA, Schmitt-Gräff A, et al. “Catastrophic systemic lupus erythematosus” with Rosai–Dorfman sinus histiocytosis. Successful treatment with anti-CD20/rutuximab [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2001; 126: 998–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohori NP, Yu J, Landreneau RJ, et al. Rosai–Dorfman disease of the pleura: a rare extranodal presentation. Hum Pathol 2003; 34: 1210–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherif J, Toujani S, Mehiri N, et al. Rosai and Dorfman disease with pleural involvement: case report. Sci World J 2008; 8: 845–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Travis WD, Colby TV, Koss MN, et al. Non-neoplastic disorders of the lower respiratory tract. King DW. ed. Atlas of nontumor pathology. 1st series, Fascicle 2 Washington, DC, USA: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 2002: 144–7 [Google Scholar]