Abstract

Tuberculosis is a ubiquitous disease and a public health problem of major importance in almost all developing and underdeveloped countries. It can involve any part of the body, including the eye. We report a case of a young child presenting with a painful blind eye with leucocoria, where a misdiagnosis of retinoblastoma was made clinically. The eye was enucleated, and subsequent pathological examination led to a final diagnosis of ocular tuberculosis. The patient was put on anti-tubercular treatment, and responded well.

BACKGROUND

Despite wide ranging efforts, tuberculosis continues to persist as a public health problem, particularly in the developing regions of the world. The worldwide spread of AIDS has ensured that developing as well as the developed nations continues to be vary of it. Pulmonary tuberculosis with ocular involvement is an uncommon disease with a possible incidence of 1.4–18% according to different diagnostic criteria.1 Although rare, tubercular involvement of eye may occur and may sometimes masquerade as a malignancy clinically. The purpose of this case is to highlight one such confusing scenario.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 6-year-old girl was admitted with complaint of redness, swelling and pain in her right eye for the previous 6 months, and lacrimation and photophobia for the last 3 months. None of family members had a similar history. She had not received any immunisation. On general examination, she had a poor physique with mild pallor, with no significant lymphadenopathy or any other important finding on complete systemic examination.

Ocular examination revealed oedematous lids, conjunctival and deep ciliary congestion, associated with a yellowish-white pupillary reflex, fixed mid dilated pupil, loss of vision and hypotony (Shoitz 5 mm Hg) in the right eye. Biomicroscopy demonstrated stromal and epithelial oedema with numerous keratic precipitates. A clinical diagnosis of retinoblastoma was made. Enucleation of the eye was performed because of suspicion of retinoblastoma in an otherwise painful blind eye. The left eye was unremarkable with visual acuity 6/6.

Routine investigations were mostly non-specific, with mild anaemia, raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), negative Mantoux test, only mild hilar lymphadenopathy on chest x ray, and normal skull skiagraphy. As the patient was very poor, she was not able to afford a CT/USG scan.

Pathologic examination

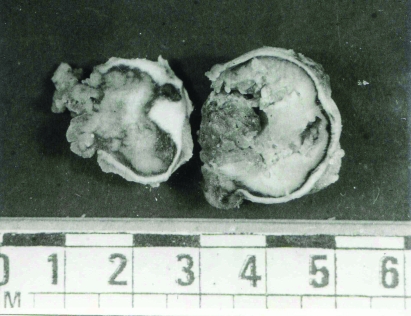

The right eyeball (2 cm in diameter) together with the optic nerve (5 mm long) was examined. Cut section revealed that the entire vitreous was filled with a yellowish necrotic mass, with some material in the anterior chamber (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Eyeball showing yellowish necrotic mass in posterior chamber.

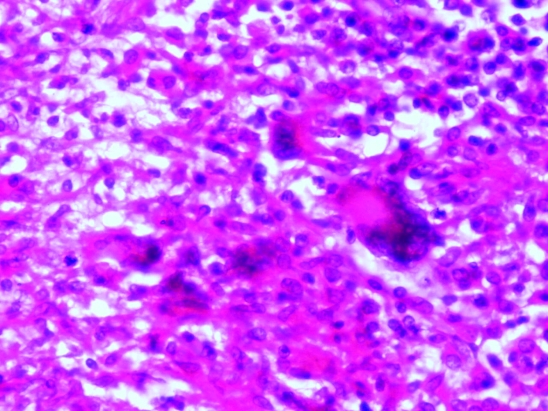

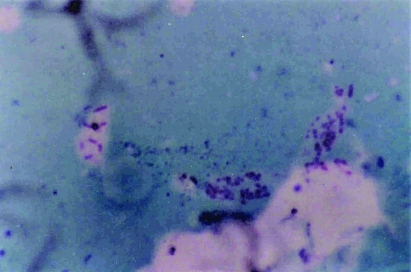

Microscopically, large granulomatous lesions involving the choroid, retina, iris and ciliary body were seen. Areas of caseous necrosis surrounded by lymphocytes, plasma cells, Langhans giant cells and epithelioid cells were present in the chorioretinal area (fig 2). The vitreous showed inflammatory reaction and caseous necrosis. There was no evidence of calcification. Period acid–Schiff staining for fungal organisms was negative. However, acid fast bacilli were identified in the necrotic retina on a modified Ziehl–Neelsen stain (fig 3). A pathologic diagnosis of ocular tuberculosis was thus made, which was further confirmed by a positive culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Figure 2.

Tuberculous eye: caseating granulomas with Langhans giant cells, lymphocytes and epithelioid cells, seen in the chorioretinal area. Haematoxylin and eosin ×500.

Figure 3.

Smear from necrotic retina showing acid fast bacilli. Modified Ziehl–Neelsen stain ×1250.

Postoperatively the patient was given anti-tubercular treatment comprising a triple drug regimen. She responded well to therapy, but did not return for follow-up after 6 months. Her HIV test was negative.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of ocular tuberculosis has been the subject of controversy due to difficulties in ocular sampling for microbiology and inexact diagnostic criteria.2 Studies conducted in the period before AIDS reported an incidence of 1–2% for ocular disease,3,4 while surveys conducted in the AIDS era have found incidence rates varying from 2.8%5 to 18%.6

Miliary dissemination may appear in eyes concomitant with the tubercular focus in the lungs, long bones, spine and kidneys; or by direct extension from adjacent structures. The optic nerve or its sheath may be the source of infection; or a posterior tuberculous abscess of the cornea may cause disseminated infection requiring enucleation.7 Clinical presentation of intraocular tuberculosis includes subretinal abscess, granulomatous anterior uveitis with scleral perforation, exudative mass in anterior chamber, and choroidal mass with panuveitis.8

Intraocular tuberculosis masquerading as ocular tumours is uncommon. The differential diagnosis with retinoblastoma is important when the disease presents as an inflamed eye, with decreased vision or blindness, leucocoria and vitreous mass with foci of calcification on CT scan and ultrasound.9 In such cases, diagnosis of tuberculosis infection is difficult; and it begins with a complete physical examination, including a sputum smear and culture, purified protein derivative (PPD) test, and chest radiograph. The presence of a systemic tuberculosis infection strongly indicates but does not prove that tuberculosis is the cause of the ocular findings. Additionally, an initial workup that yields negative results should not eliminate tuberculosis from the differential diagnosis.10

The use of complementary tests is not definitive but may help in achieving a presumptive diagnosis. Fluorescein angiography of choroidal active lesions shows early phase hyperfluorescence with late leakage. Cicatricial lesions show early phase blockage with late staining. Indocyanine green angiography shows early and late phase blockage by choroidal tuberculomas. The number of lesions observed in the indocyanine green angiography is greater than in the fluorescein test. The ultrasound is highly variable; the lesions show low internal reflectivity and a rich vascular bed.9

A definitive diagnosis is possible when M tuberculosis can be visualised in, cultured from, or its DNA amplified from the involved tissue.10 Whereas cultures may easily be obtained in patients with external disease, in most ocular tuberculosis cases, culture and biopsy of the involved tissues is not practical. When performed, aqueous and vitreous paracentesis have generally failed to yield positive bacterial culture results. Diagnosis based on detection of mycobacterial DNA through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is becoming the method of choice. Advantages of PCR include rapid test results and the ability to test a very small sample. By comparison, cultures may require several weeks for a positive result. Mycobacterial DNA has been detected via PCR in a variety of tissues, including eyelid skin, the conjunctiva, aqueous and vitreous humour, fixed choroidal tissue, subretinal fluid, epiretinal membranes, and several non-ocular tissues. There have also been reports of testing for tuberculosis antigens, such as cord factor antigen, via enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Although further investigations are needed to determine the sensitivity and specificity of PCR and ELISA testing for tuberculosis in ocular tissues, these techniques have added a valuable alternative for the diagnosis of intraocular tuberculosis infection.10

In our case, apart from a raised ESR and hilar lymphadenopathy, both rather non-specific in an Indian scenario, there was no definite clinical or radiological evidence of tuberculosis, suggesting this case to be extrapulmonary ocular tuberculosis. However, as tuberculosis is so prevalent in India, with the majority of the population being exposed to tubercular bacilli, the possibility of a remote asymptomatic tubercular infection leading to development of a quiescent extraocular/ocular focus with recent reactivation cannot be entirely ruled out. Some authors have also proposed that choroidal tuberculosis may represent an allergic response, wherein intermittent bacillaemia or tuberculo-proteinaemia has excited a reaction in previously hypersensitised tissue.11 Such reactivation is possible by exposure to tuberculin or protein such as milk/casein.8,11

It may be concluded that although intraocular malignancy, developmental anomalies and parasitic lesions are more likely causes of leucocoria in children, an ophthalmologist should be aware of the possibility of intraocular tuberculosis; a tuberculin test or, if possible, a PCR test should be included among the investigations in order to prevent unnecessary enucleation due to a mistaken diagnosis of retinoblastoma.

LEARNING POINTS

Incidence of ocular tuberculosis has increased since the spread of AIDS.

An ophthalmologist should always be aware of the possibility of intraocular tuberculosis.

Ocular examination should be routinely performed in patients with proven or suspected tuberculosis.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupta V, Gupta A, Rao NA. Intraocular tuberculosis – an update. Surv Ophthalmol 2007; 52: 561–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helm CJ, Holland GN. Ocular tuberculosis. Surv Ophthalmol 1993; 38: 229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donahue, HC Ophthalmologic experience in a tuberculosis sanatorium. Am J Ophthalmol 1967; 64: 742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldenburg M, Fabricant ND. The eye in the tuberculous patient. Trans Sect Ophthalmol Am Med Assn 1930: 135 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beare NA, Kublin JG, Lewis DK, et al. Ocular disease in patients with tuberculosis and HIV presenting with fever in Africa. Br J Ophthalmol 2002; 86: 1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouza E, Merino P, Munoz P, et al. Ocular tuberculosis. A prospective study in a general hospital. Medicine (Baltimore) 1997; 76: 53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mortada A. Tuberculoma of the orbit and lacrimal gland. Br J Ophthalmol 1971; 55: 565–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biswas J, Madhavan HN, Gopal L, et al. Intraocular tuberculosis. Clinicopathologic study of five cases. Retina 1995; 15: 461–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonfioli Adriana A, de Miranda Silvana S, Campos Wesley R, et al. Tuberculosis. Seminars in Ophthalmology 2005; 20: 169–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson JM, Albert DM. Ocular Tuberculosis. Arch Ophthalmol 2005; 123: 844–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal PK, Nath J, Jain BS. Orbital involvement in tuberculosis. Ind J Ophthalmol 1977; 25: 12–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]