Abstract

Buerger disease (thromboangiitis obliterans) is a non-atherosclerotic segmental inflammatory disease strongly associated with tobacco use, and it affects small and medium-sized blood vessels in the upper and lower extremities. The only known treatment for this disease is complete discontinuation of tobacco use. This report describes the case history of a woman with Buerger disease treated with the oral dual endothelin receptor antagonist bosentan. It is believed that this is the first description in the literature of this use for bosentan.

BACKGROUND

Buerger disease, or thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO), is a non-atherosclerotic segmental inflammatory disease strongly associated with tobacco use.1 It generally affects the small and medium-sized arteries, veins and nerves in the upper and lower extremities, including the palmar, plantar, tibial, peroneal, radial, cubital and digital arteries of the hands and feet. Symptoms generally begin with coldness of the fingers and toes and intermittent claudication, then progress to pain at rest and ulcerous lesions on the extremities that can necessitate amputation.

There is no well-established treatment for this disease. Aspirin is often prescribed; however, its benefits (and those of other antiplatelet aggregation agents) have not been confirmed in a controlled study. Surgical techniques are limited in scope and usefulness,1,2 although omentum autografts have shown encouraging results in some groups.3 Cessation of tobacco use is the only proven method of preventing disease progression and reducing amputation rates.4

Bosentan, an oral dual endothelin-1 (ET-1) receptor antagonist, has demonstrated efficacy, with a favourable safety profile, in two randomised controlled clinical trials (RAPIDS-1 and RAPIDS-2) for the treatment of digital ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis,5 and it may be beneficial to the treatment of Raynaud phenomenon.6 Bosentan exhibits anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic properties and may exert a selective vasodilatory effect on the vascular bed affected by TAO, comparable to the effects observed in systemic sclerosis patients with digital ulcers.

Here we present a case history of a female patient with TAO treated with bosentan.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 36-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with a 6-month history of the insidious onset of a necrotic skin lesion on the inside surface of her left great toe. She had signs of perilesional inflammation, ischaemic cyanotic lesions in the pads of the third and fourth toes of the right foot and pinpoint necrotic lesions around the toenails (fig 1). The patient experienced pain at rest and had paraesthesia in the toes of both feet. Symptoms had appeared 8 months previously, with pain on walking, pallor and dysaesthesia in both feet. The patient had smoked 30–40 cigarettes per day since puberty. She had suffered a superficial venous thrombophlebitis in the area of the internal saphenous vein 10 years previously and had chronic phlebostasis, but no other cardiovascular risk factors.

Figure 1.

Digital ulcers before treatment with bosentan.

INVESTIGATIONS

There was no previous history of Raynaud phenomenon, mouth ulcers, skin problems affecting other areas, or notable axial or peripheral joint symptoms. On physical examination, reduced intensity was detected on palpation of pedal pulses in both feet. She had palpable radial and ulnar pulses and Allen’s test was positive in both upper extremities. Magnetic resonance angiography of the lower limbs revealed a normal tibioperoneal trifurcation and a lack of continuation into the foot of the right dorsal pedia and peroneal and the left dorsal pedia, plantar and peroneal arteries (fig 2). The ankle–arm index was normal in both lower limbs (right 1.18, and left 1.12), with loss of the triphasic flow pattern in the right lower limb pedal artery and the left posterior tibial artery.

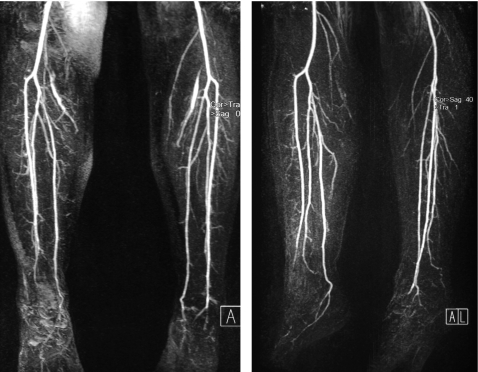

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance angiography of the lower limbs. Segmental occlusions of the pedal arteries and corkscrew collateral arteries were found.

Results of standard laboratory blood tests were within the normal range. Tests for C-reactive protein, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, anti-DNA antibodies, antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, anti-Ro antibodies, anti-Sm antibodies, anti-Jo-1 antibodies and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. Levels of complement C3 and C4, and thyroid stimulating hormone, were normal. Creatinine clearance was 103 ml/min with no proteinuria in a 24 h period. Tests for anticardiolipin antibodies were negative, as were tests for syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B and C. Diagnoses of cardiogenic or aortic embolism, early-onset occlusive atherosclerotic disease, collagen disease, and hypercoagulable state were excluded. The patient therefore satisfied clinical criteria for diagnosis of TAO.1,7

TREATMENT

While an inpatient, the patient stopped smoking and was treated with intravenous iloprost for 21 days, and this resulted in diminished pain and reduced swelling in the distal areas of her toes, although ischaemic lesions persisted. Two months after iloprost treatment, and despite not smoking, a dry necrotic lesion persisted around the nail of the patient’s left great toe. Following recurrence of pain at rest in the pads of the toes on both feet, accompanied by marked cyanosis and paresthesia for 2 weeks, the patient started treatment with bosentan on a compassionate use basis for which the patient gave informed, written consent.

Bosentan was administered at 62.5 mg twice daily for the first 4 weeks and uptitrated to 125 mg twice daily for a further 5 months, with monthly monitoring of alanine and aspartate aminotransferase levels. No clinical nor biochemical abnormalities were detected, and no adverse reactions were observed.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

One month after starting treatment, the pain at rest and paraesthesia had subsided, and cyanosis of the pads of the toes had disappeared. The patient recovered the triphasic flow pattern in the right lower limb pedal artery and the left posterior tibial artery. After 2 months of treatment, the trophic lesions had healed completely (fig 3) and after 6 months of therapy, the patient was asymptomatic. She remained asymptomatic for 4 months after finishing treatment.

Figure 3.

Trophic lesions healed completely after treatment with dual endothelin-1 receptor antagonist.

DISCUSSION

Although the aetiology of TAO is poorly understood, the role of tobacco use in its origin and progression is well established. Changes in endothelium-dependent vasodilatation8 and inflammatory processes affecting the elastic lamina9 are two processes reported to underlie TAO pathology. TAO is characterised histopathologically by highly cellular vessel wall inflammation, giant cell foci, and hypercellular thrombi coexisting with microabscesses and leucocytes, neutrophils and multinucleated giant cells. While endothelium-dependent peripheral vasodilatation is affected in patients with TAO, the endothelium-independent dilatation mechanisms may remain intact.8

The most effective therapeutic strategy in TAO is immediate cessation of tobacco use, as even modest tobacco use (including nicotine patches) can impair healing.10,11 Patients may continue to present with claudication or Raynaud phenomenon after smoking cessation.1 Intravenous iloprost has been observed to be a superior treatment to aspirin in terms of pain relief at rest and healing of trophic lesions. Iloprost may also reduce the risk of amputation.12

In this patient, intravenous iloprost and complete cessation of tobacco use were insufficient to alleviate pain at rest or improve trophic lesions. Surgery was not a viable option because the lesions were so distal.

This case is, as far as we know, the first to report the treatment of TAO with bosentan, a dual ET-1 receptor antagonist. Recent studies have suggested that endothelial damage caused by the vasoconstrictive, pro-inflammatory and fibrotic effects of ET-1 may trigger peripheral arterial occlusive disease (unpublished observation). The anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic and selective vasodilatory properties of bosentan have been shown to alleviate pain at rest and reduce the size of ischaemic ulcers caused by damage to the microcirculation.5

This patient experienced no adverse effects during 6 months of bosentan treatment or during follow-up. A substantial reduction in ulcer size and complete relief of ischaemic pain at rest was observed following 1 month of treatment. After 2 months of treatment, the ulcers were completely healed. The patient was asymptomatic at the end of therapy and remained so at the time of writing (4 months after the cessation of bosentan treatment).

This report has a limitation in that there is no diagnostic test to confirm the cessation of smoking, though the patient stated firmly that this was the case. It is very unlikely, but some patients with Buerger disease improve spontaneously even if they continue to smoke.

LEARNING POINTS

Bosentan may represent a future therapeutic option for treatment of thromboangiitis obliterans, and merits further evaluation in larger controlled, randomised clinical studies.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Xavier Lloria for his help with the English version of the article.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Olin JW, Young JR, Graor RA, et al. The changing clinical spectrum of thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). Circulation 1990; 82(5 Suppl): IV3–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasajima T, Kubo Y, Inaba M, et al. Role of infrainguinal bypass in Buerger’s disease: an eighteen-year experience. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1997; 13: 186–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal VK. Long-term results of omental transplantation in chronic occlusive arterial disease (Buerger’s disease) and retinal avascular diseases (retinitis pigmentosa). Int Surg 2007; 92: 174–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olin JW. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 864–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korn JH, Mayes M, Matucci Cerinic M, et al. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: prevention by treatment with bosentan, an oral endothelin receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50: 3985–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Nardi N, et al. Successful treatment of severe Raynaud’s phenomenon with bosentan in four patients with systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004; 43: 1454–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shionoya S. Diagnostic criteria of Buerger’s disease. Int J Cardiol 1998; 66(Suppl 1): S243–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makita S, Nakamura M, Murakami H, et al. Impaired endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in peripheral vasculature of patients with thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). Circulation 1996; 94(9 Suppl): II211–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi M, Ito M, Nakagawa A, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of arterial wall cellular infiltration in Buerger’s disease (endarteritis obliterans). J Vasc Surg 1999; 29: 451–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joyce JW. Buerger’s disease (thromboangiitis obliterans). Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1990; 16: 463–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lie JT. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum 1988; 31: 812–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiessinger JN, Schafer M. Trial of iloprost versus aspirin treatment for critical limb ischaemia of thromboangiitis obliterans. The TAO Study. Lancet 1990; 335: 555–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]