Abstract

The present report concerns a patient who presented with a 4-day history of left-sided facial pain arising from a pre-existing dental infection and progressive shortness of breath. The patient had a previous diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and was being treated with methotrexate. The rapid development of a right eye proptosis necessitated urgent decompression with a lateral canthotomy and cantholysis. Imaging revealed a left facial abscess, cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST), bilateral internal jugular thrombosis and multiple lung abscesses. Blood cultures yielded Streptococcus constellatus, a member of the Peptostreptococcus family. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with respiratory failure and septic shock. She was treated with intravenous meropenem and clindamycin, and anticoagulated. Despite early intervention, the patient developed a middle cerebral artery infarct. Over a 3-week period she was gradually weaned from vasopressor and ventilatory support.

BACKGROUND

This case illustrates the importance of prompt assessment and treatment of dental infections in patients who are immunosuppressed. Cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) indirectly caused by mandibular dental infection is rare. Furthermore, the associated proptosis, pulmonary abscesses and late cerebral vascular accident (CVA) are unusual complications. CST, proptosis and CVA occur as a result of retrograde thrombophlebitic spread and relate directly to the anatomy of head and neck venous drainage. This highlights the frequently underestimated risks posed by facial and oropharyngeal infections.

CASE PRESENTATION

Our patient, a 54-year-old woman of Indian descent, presented to our Emergency Department with a 4-day history of left sided facial pain, exacerbated by mastication. Dental evaluation revealed a dental abscess and gross caries involving three teeth of the left mandible (molars 36, 37 and 38). She experienced increasing shortness of breath but denied other symptoms including haemoptysis and chest pain.

The patient’s medical history included hypertension and a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis for which she had been treated with methotrexate for the preceding 3 years. She had never smoked, did not consume alcohol or illicit drugs and had worked in administration. She had previously travelled to India four times in the last decade, but had no known tuberculosis contacts. There was no significant family history.

While being assessed in the Emergency Department she rapidly developed a right eye proptosis (contralateral to the dental abscess). Ophthalmological review confirmed a 4 mm right proptosis and mild abduction deficit on right gaze (fig 1). Right Snellen visual acuity was 6/12 with a raised intraocular pressure of 35 mm Hg. The left eye was normotensive with Snellen acuity of 6/6. Slit lamp biomicroscopy revealed conjunctival chemosis and dilated indirect fundoscopy was non-contributory. There was no ocular bruit. Optic nerve function was intact and an urgent decompressive lateral canthotomy and cantholysis were performed in order to avoid optic nerve compromise.

Figure 1.

Colour photograph showing proptosis of right eye.

The patient was afebrile on presentation, with a resting tachycardia of 110 beats/min and a blood pressure of 124/77 mm Hg. Capillary refill and peripheral perfusion were normal. No stigmata of infective endocarditis were found. Jugular venous pressure was not elevated and no murmurs were noted on auscultation. Respiratory rate was 28 breaths/min, saturating at 97% on room air, and fine inspiratory crepitations were heard at the lung bases. There was no evidence of deep venous thrombosis of the lower limbs.

Following incision and drainage of the dental abscess, the patient developed respiratory failure and septic shock resulting in admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

INVESTIGATIONS

A neutrophilia was present with a total white cell count of 17.1×109/litre and an elevated C-reactive protein level of 316 mg/litre. Blood gas analysis showed a compensated metabolic acidosis with a pH of 7.34 and a negative base excess of −12 mmol/litre. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody testing was unremarkable and a thrombophilia screen including lupus anticoagulant and anti-cardiolipin antibodies was normal. Blood cultures together with aspirates from the abscess grew Streptococcus constellatus, a member of the Peptostreptococcus family. Sputum cultures for Mycobacterium and Aspergillus were negative, as was sputum cytology. HIV testing was also negative.

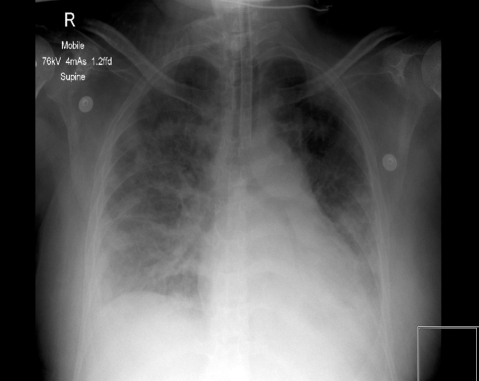

Chest x ray showed circular opacities throughout both lung fields (fig 2). A reticular interstitial pattern distributed throughout bilateral mid and lower zones was suggestive of a previously undiagnosed fibrotic lung disease, likely rheumatoid in nature or secondary to methotrexate use.

Figure 2.

Anteroposterior (AP) radiograph showing multiple bilateral circular opacities.

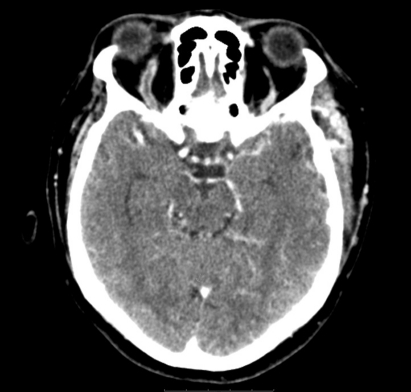

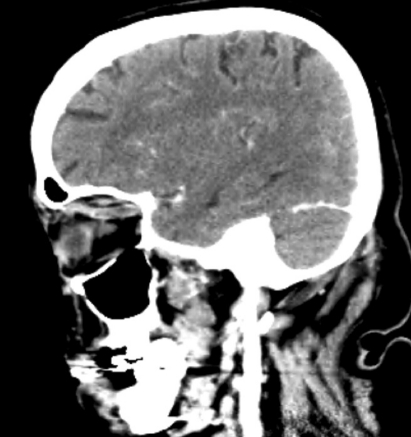

A 64-slice CT scan revealed a facial abscess involving the left pterygoid muscle and extending into the superficial, deep and infratemporal spaces. Thrombosis was seen in the cavernous sinus (CS), left retromandibular vein, bilateral internal jugular veins and right superior ophthalmic vein (figs 3 and 4). There were no orbital masses and paranasal sinuses were unremarkable. Multiple round, peripheral lung lesions were noted bilaterally, measuring up to 2 cm (fig 5).

Figure 3.

Post contrast venous phase CT scan of the head (axial view) showing an enlarged “S” shaped right superior ophthalmic vein with associated proptosis.

Figure 4.

Sagittal CT scan of the head demonstrating an enlarged, tubular right superior ophthalmic vein.

Figure 5.

Axial CT chest scan showing bilateral circular peripheral opacities.

Transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiography yielded no valvular pathology.

Doppler ultrasonography of the carotid arteries was unremarkable.

MRI scans were not performed following admission to the ICU owing to the critical nature of the patient’s illness and the lack of additional diagnostic information likely to be gained from this investigation.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Occult cancer with lung metastasis (and coexisting thrombophilia), rheumatoid nodules, cardiogenic septic emboli, vasculitis (eg, Wegener granulomatosis), internal carotid artery aneurysm.

TREATMENT

Right lateral canthotomy and cantholysis were performed to relieve pressure on the optic nerve and topical ocular antihypertensive drugs were given to reduce intraocular pressure.

Intravenous meropenem and clindamycin were used initially and later rationalised to clindamycin alone for a total of 6 weeks of treatment.

The patient was anticoagulated with subcutaneous enoxeparin and low dose aspirin prior to commencement of 6 months of treatment with warfarin.

Three offending molars were extracted and simultaneous intraoral incision and drainage of the left face fascial space was performed under general anaesthetic. Incision and drainage was repeated in order to achieve complete drainage.

Supportive treatment in the ICU included vasopressor and ventilatory support and a tracheostomy to facilitate weaning.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient was weaned from vasopressor and ventilatory support in the ICU. The lung lesions gradually resolved with antibiotic treatment, signifying an infective process as the most likely aetiology. The proptosis progressed from unilateral to bilateral before resolving over a 3-week period together with the ophthalmoplegia.

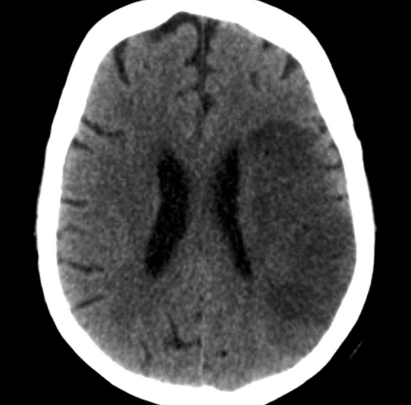

Despite early anticoagulation, the patient proceeded to develop a left middle cerebral artery infarct causing right-sided neglect, dysphasia, dysphagia, homonymous hemianopia and hemiplegia (fig 6).

Figure 6.

Axial CT scan of the head showing left middle cerebral artery territory infarct.

DISCUSSION

In the early antibiotic era, odontogenic infections accounted for less than 10% of CST cases.1–3 A literature search revealed that most cases of odontogenic septic CST cite a maxillary origin. Aside from our case, we were only able to find two other cases that claim a mandibular dental nidus.4,5 Our case is unusual in this respect and in its complication by proptosis, distal infective emboli causing lung abscesses and middle cerebral artery thrombosis.

This case highlights the clinical anatomy of facial and oropharyngeal venous drainage to the CS. Infections of these areas can induce local venous congestion and the creation of an inflammatory procoagulant cascade with subsequent thrombophlebitis.6 Retrograde proliferation of this process is facilitated by a paucity of valves in the veins of the head and neck. In our patient, we postulate that such spread occurred via the retromandibular vein and the pterygoid plexus, culminating in CST and superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis (with later middle cerebral artery thrombosis). Other suggested routes of spread in mandibular infections causing CST include direct spread to the pterygoid plexus from the alveolar ridge and spread to the carotid sheath via the parapharyngeal space.4,5 Superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis has also been documented in relation to maxillary dental infections.7 A similar case involving Streptococcus milleri of dental origin resulted in a comparable presentation and clinical picture (although, unlike our case, septic emboli caused intracerebral and intraorbital abscesses in addition to CST).8

Ophthalmological signs initially arise from venous congestion within orbital veins secondary to impaired drainage to a thrombosed CS. In all, 95% of CST cases (ours included) develop visible signs of chemosis, periorbital oedema and proptosis.9 In addition, the advancement from unilateral to bilateral proptosis is pathognomonic of CST.1,10 Compression of one or more of cranial nerves III, IV, VI, V1 and V2 results in impedance of extraocular movement as projections of these nerves lie within or against the CS (in this case, cranial nerve VI). Other structures passing through the CS include the internal carotid arteries, branches of which supply the cerebral hemispheres. Hemispheric infarction and ensuing hemiplegia is a recognised complication of septic CST.11 Further thrombophlebitic spread may give rise to meningitis or subdural empyema. Although efficacy remains undetermined, early adjunctive anticoagulation should be considered following radiological exclusion of haemorrhagic sequelae of CST.1

In our case, the degree of infection and rate of thrombophlebitic spread may relate to immunosuppression originating from pre-existing rheumatoid arthritis and/or its associated treatment with methotrexate. Staphylococcus aureus is the causative agent in more than half of septic CST cases,4,12,13 most of which arise from sphenoidal and ethmoidal sinus infections.10,13 Mixed organisms are usually found in odontogenic sources and these include streptococci (notably of the β haemolytic variety) and anaerobes.8,14 Early addition of meropenem and clindamycin was therapeutic for the initial infective focus and CST, and also the septic pulmonary deposits.

LEARNING POINTS

Dental and sinus sources of infections should not be overlooked in patients who are immunosuppressed.

Rapid onset of ocular signs (ophthalmoplegia, chemosis, proptosis and facial swelling), in the context of a dental, oropharyngeal, facial or sinus infection, should prompt the possible diagnosis of cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST).

While Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen causing CST, other organisms such as streptococci and anaerobes should be considered when selecting initial antibiotic therapy.

Treatment of CST includes high dose broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics, anticoagulation and drainage of unresolving suppurations.

Attention should be given to any associated complications, and multidisciplinary input is vital to optimise outcome.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhatia K, Jones NS. Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis secondary to sinusitis: are anticoagulants indicated? A review of the literature. J Laryn Otol 2002; 116: 667–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw RE. Cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis: a review. Br J Surg 1952; 40: 40–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harbour RC, Trobe JD, Ballinger WE. Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis associated with gingivitis and parapharyngeal abscess. Arch Ophthalmol 1984; 102: 94–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman DP, Picerno NA, Porubsky ES. Cavernous sinus thrombosis complicating odontogenic parapharyngeal space neck abscess: a case report and discussion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000; 123: 744–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzeo V. Cavernous sinus thrombosis. J Oral Med 1974; 29: 53–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esmon CT, Taylor FB, Jr, Snow TR. Inflammation and coagulation: linked processes potentially regulated through a common pathway mediated by protein C. Thromb Haemost 1991; 109: 582–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grassi MA, Lee AG, Kardon R, et al. A lot of clot. Surv Ophthalmol 2003; 48: 555–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Udaondo P, Garcia-Delpech S, Diaz-Llopis M, et al. Bilateral intraorbital abscesses and cavernous sinus thromboses secondary to Streptococcus milleri with favourable outcome. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2008; 24: 408–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Southwick FS, Richardson EP, Jr, Swartz MN. Septic thrombosis of the dural venous sinuses. Medicine 1986; 65: 82–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmmed A, Camilleri A, Small M. Cavernous sinus thrombosis following manipulation of fractured nasal bones. J Laryngol Otol 1996; 110: 69–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visudtibhan A, Visudhiphan P, Chiemchana S. Cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis in children. Pediatr Neurol 2001; 24: 123–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kriss T, Kriss V, Warf B. Cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis: case report. Neurosurgery 1996; 39: 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebright JR, Pace MT, Niazi AF. Septic thrombosis of the cavernous sinuses. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161: 2671–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogundiya DA, Keith DA, Mirowski J. Cavernous sinus thrombosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1984; 102: 94–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]