Abstract

Introduction:

Spontaneous haemoperitoneum due to rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a surgical emergency and may have catastrophic outcomes.

Clinical picture:

A 62-year-old male presented with nausea, dizziness and low back pain. There was no history of malignancy. Physical examination revealed a surgical abdominal emergency, but there was no physical finding that pointed towards a specific diagnosis. Laboratory studies revealed decreased haematocrit (27.6%) and increased INR (2.8) levels. A computed tomography scan showed a tumoral lesion within the fourth segment of the liver and fluid collection (haemoperitoneum) with normal vascular and intra-abdominal structures.

Treatment:

Exploratory laparotomy was performed; the appearance of the liver was cirrhotic and nodular. Actively bleeding tumoral lesion was confirmed in fourth segment of the liver, “packing” applied with sponges to stop bleeding. On the post-operative day 22, the patient was discharged.

Conclusions:

Spontaneous rupture of HCC is rare and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of non-traumatic spontaneous haemoperitoneum.

BACKGROUND

Spontaneous haemoperitoneum may be extremely difficult to diagnose and may have a catastrophic outcome. It most commonly presents as acute abdominal pain, which may be accompanied by abdominal distension, hypotension and tachycardia.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is common in areas with endemic hepatitis B or C. The incidence of spontaneous rupture of HCC is about 10%.1,2 It is a true life-threatening emergency condition that causes spontaneous haemoperitoneum and development of shock. It may occur as a terminal event in patients with advanced disease or may present in an otherwise healthy individual.3 Most of these patients have been seen in an emergency department (ED). The hospital mortality rate of ruptured HCC has been high, ranging from 33% to 67%.3,4 The diagnosis is missed or delayed because of lack of familiarity with the disease, especially in countries where its incidence is low. Also, variations in clinical presentation pose a challenge to the clinician in view of the need for rapid diagnosis and management.

In the case presented below an active male presented to our ED with low back pain and vertigo, but his clinical status progressed and needed immediate fluid resuscitation and, later, emergency surgery was required due to the development of hypovolaemic shock.

CASE PRESENTATION

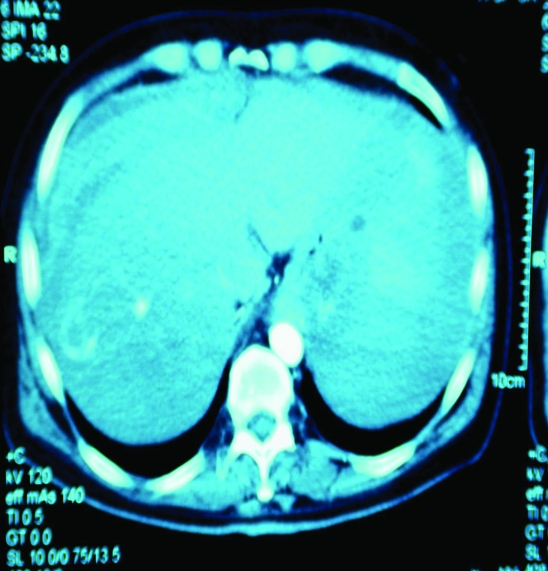

A 62-year-old male was brought by ambulance to the ED at 11.05 a.m. with a blood pressure (BP) of 115/70 mmHg, pulse rate (PR) of 137 beats/min and respiratory rate (RR) of 26 breaths/min. The patient had a normal mental status and was able to give a reliable history. The patient denied any significant past medical or surgical history except that he was hepatitis B carrier. He denied trauma. He also denied any history of recent travel. He stated that at about 08.00 a.m. he woke up with a complaint of nausea and vertigo. He felt a sharp low back pain and experienced a presyncope when he tried to stand up. After waiting a short time, the patient’s back pain worsened so he called for an ambulance. He denied loss of consciousness and head trauma associated with the event. On arrival in the ED, two large bore IV lines were established and fluid resuscitation was begun. His routine blood tests were sent. Supplemental oxygen 100% was administered by a non-rebreather mask. Five units of packed red blood cells were ordered for type and cross-match. On physical examination, the patient had abdominal distension with diffuse tenderness. There were no stigmata of liver disease. His vital signs did not improve, yielding a BP of 80/40 mmHg and PR of 150 beats/min. Two units of packed red blood cells were given via a central jugular catheter. An abdominal ultrasound was rapidly performed with a presumptive diagnosis of aortic dissection. The aorta was normal but there was free intraperitoneal fluid in the abdomen that looked like a haemorrhage. Surgery consultation was obtained along with a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen (see fig 1). The CT scan showed a tumoral lesion within the fourth segment of the liver and fluid collection (haemoperitoneum) with normal vascular and intra-abdominal structures.

Figure 1.

The computed tomography image shows high attenuation fluid (peritoneal blood) and possible tumoral lesion.

Following the CT scan, the patient underwent an emergency exploratory laparotomy; the appearance of the liver was cirrhotic and nodular. An actively bleeding tumoral lesion was confirmed in the fourth segment of the liver; to control the bleeding, the liver was gauze packed and the abdomen closed. This procedure was successful in arresting blood loss, after which the patient stabilised. No resection was performed. During the surgery, 2 units of packed red blood cells and 4 units of fresh frozen plasma were given. On post-operative day 22 the patient was discharged.

The initial laboratory findings later revealed: haematocrit: 19.2, prothrombin time: 17.8 s (reference range, 11–13), INR: 1.60; serum alanine aminotransferase, 57 U/l (10–37); aspartate aminotransferase, 93 U/l (10–40); alkaline phosphatase, 238 U/l (0–270); γ-glutamyltransferase, 55 U/l (7–49); amylase, 75 U/l (0–220); total bilirubin, 0.54 mg/dl (0.2–1.0); direct bilirubin, 0.06 mg/dl (0–0.3); and albumin, 3.1 mg/dl (3.5–5.4).

DISCUSSION

The incidence of HCC is increasing in Western countries. Spontaneous rupture is a life-threatening presentation and is associated with an overall mortality rate of 50% and poor long-term survival rates.5 Typically, HCC is a hypervascular tumour and is composed of abnormal blood vessels; any small increase in vascular load owing to portal hypertension or mechanical injury results in tears in the vessel wall producing haematoma. Vascular invasion with venous obstruction is likely to contribute to increased pressure within the tumour. Because the overlying hepatic parenchyma is frequently cirrhotic, the haemorrhage may further extend into the intraperitoneal space.6

The clinical presentation of spontaneous rupture of HCC has been variable; therefore, in some cases, there were delays, misdiagnoses or incidental discovery.7 Symptoms may be abdominal pain, syncope, hypotension or abdominal fullness. In our patient low back pain and orthostatic symptoms were marked. Hepatocellular rupture may result in haemoperitoneum and development of shock. Although poor prognosis has been reported in the past with more than three-quarters of patients dying within 1 month, recent reports have shown a significant decrease in mortality rate (32%, 30-day mortality rate).8 The reasons are thought multiple. First early recognition of this complication has been facilitated by the use of imaging with CT and ultrasound. CT rather than angiography is the first-line modality for detection of rupture. CT can confirm the diagnosis of ruptured HCC and can also help in assessing other organs if the diagnosis is not clear prior to imaging. Also it allows for an assessment of the entire liver, including the portal vein, which aids in determining the feasibility of embolisation and resection.9 Also, an emergency physician’s presumptive diagnosis and recognition of the importance of aggressive initial resuscitation to correct hypovolaemic shock is a factor of decreased mortality.

LEARNING POINTS

In populations at high risk for HCC, emergency physicians should be alert to this fatal entity.

Spontaneous rupture of HCC should be considered in the differential diagnosis of non-traumatic intra-abdominal haemorrhage when a patient presents to the ED with shock and abdominal, low back pain.

The primary objective in the management of these patients is to achieve haemodynamic stabilisation by non-surgical, surgical or conservative methods.

The mortality and morbidity rate is high because these patients usually have poor reserve and advanced disease. However, spontaneous rupture of HCC is a potentially salvageable complication of HCC.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miyamoto M, Sudo T, Kuyama T. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review of 172 Japanese cases. Am J Gastroenterol 1991; 86: 67–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee CC, Kim SH, Crupi RS. Emergency department presentation of spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Emerg Med 2002; 23: 83–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen CY, Lin XZ, Shin JS, et al. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review of 141 Taiwanese cases and comparison with nonrupture cases. J Clin Gastroenterol 1995; 21: 238–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. Management of spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: single center experience. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 3725–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Battula N, Srinivasan P, Madanur M, et al. Ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma following chemoembolization: a western experience. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2007; 6: 49–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim PT, Su JC, Buczkowski AK, et al. Computed tomography and angiographic ınterventional features of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma: pictorial essay. Can Assoc Radiol J 2006; 57: 159–68 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen WK, Chang YT, Chung YT, et al. Outcomes of emergency treatment in ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2005; 23: 730–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan FL, Tan YM, Chung AY, et al. Factors affecting early mortality in spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. ANZ J Surg 2006; 76: 448–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanematsu M, Imaeda T, Yamawaki Y, et al. Rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: predictive value of CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; 158: 1247–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]