Abstract

The world has experienced a marked shift in the global BMI distribution towards reduced undernutrition and increased obesity. The collision between human biology, shaped over the millennia and modern technology, globalization, government policies and food industry practices have worked to create far-reaching energy imbalance across the globe. A prime example is the clash between our drinking habits and our biology. The shift from water and breast milk as the only beverages available, to a vast array of caloric beverages was very rapid, shaped both by our tastes and aggressive marketing of the beverage industry. Our biology, shaped over millennia by daily consumption of water and seasonal availability of food, was not ready to compensate for the liquid energies. Other dietary changes were similarly significant, particularly the shift towards increased frequency of eating and larger portions. The roles of the food and beverage production, distribution and marketing sectors in not only shaping our diet but also accelerating these changes must be understood. Apart from the role of beverages, there is much less consensus about the role of various components of our diet in energy imbalance. Understanding the determinants of change in the key components of our diet through an array of research provides insights into some of the options we face in attempting to attain a great balance between energy intake and expenditures while creating an overall healthier dietary pattern. A few countries are systematically addressing the causes of poor dietary and physical activity patterns and high energy imbalance.

Keywords: Nutrition transition, Obesity, Sugar-sweetened beverages

The shifts in global dietary patterns in terms of food sources, modes of processing and distribution over the past several decades have led to a world dominated by highly processed foods and drink. The concomitant shifts in the frequency of eating, the preparation of food and beverages and overall energy imbalance are being explored by scholars. The disappearance of water and milk from the diets of children and its replacement with an array of sugar-sweetened beverages are just one example of these shifts.

These changes, which decades ago began to emerge in higher-income countries, today reach billions of individuals across the globe. There are a few countries where major shifts towards increased overweight among adults are not documented, while undernutrition is slowly being reduced in many countries.

Although many shifts towards great energy imbalance were partially linked with reduced activity in physical activity in all phases of work (e.g. the effects of reduced activity in home production, transport, market activity and leisure have all been documented for China(1-4)), the greatest potential for reducing the current energy imbalances will be found in increased physical activity.

A few countries have begun to systematically search for ways to enhance our understanding and use of more basic food stuffs. This is why the UK has instituted cooking classes for all youth(5-7). This is why there is a greater push towards increasing incentives for low-income consumers to consume fruits and vegetables purchased in local farmers markets in the USA(8). However, the majority of individuals in many countries have moved to a point where food preparation requires less than 30 min per day and processed foods represent the bulk of consumption(9).

The levels of overweight have increased across the globe, diets are changing at a most rapid pace and apart from major actions by a few governments nothing is standing between these changes and a globe where increasing proportions of the population are overweight. With it has come a large increase in nutrition-related noncommunicable diseases(10-14).

Dietary changes

In the last 20–30 years, the world has reduced its water intake, shifted towards sugar-sweetened beverages, increased its proportion of food that is sweetened and ultra processed and reduced its intake of many health components of our diet, including legumes, fruits and vegetables(10,14-17). The speed of change is astounding.

The clash of biology, shaped over tens of thousands of years, with modern marketing is personified in the beverage area(18).

We are what we drink

The field of nutrition does not fully understand the reasons why when we drink a beverage based on fat, carbohydrates or protein, we do not compensate by reducing food intake; however, when we eat that same food (e.g. watermelon, coconut and cheese), we reduce our intake of other food(19). Beginning with the research by Mattes and his colleagues(20-22) and followed by extensive work by scholars across the globe, it is apparent that we do not compensate for beverage energies(21-32). These studies argue that any type of sweetener with energies in liquid beverages may not suppress intake of solid foods to help maintain energy balance. This may occur week to week as in the 6-week DellaValle et al. study of meal to meal or day to day(30). The reduced compensation occurs in both men and women(32). The quantity of calorically sweetened beverages also increases as the portion size increases(32). Many other studies demonstrate this lack of compensation(24-29). See also the review by Mattes(33).

Based on this, we looked at the evolution of beverage consumption patterns(18). A consideration of our evolutionary history may help us to explain our poor compensatory response to energies from fluids. We reviewed the history of eight important beverages: milk, beer, wine, tea, coffee, distilled alcoholic beverages, juice and soft drinks. We arrived at two hypotheses. First, human subjects may lack a physiological basis for processing carbohydrate or alcoholic energies in beverage because only breast milk and water were available for the vast majority of our evolutionary history. Alternatives to those two beverages appeared in the human diet no more than 11 000 years ago, but Homo sapiens evolved between 100 000 and 200 000 years ago. Second, carbohydrate and alcohol-containing beverages may produce an incomplete satiation sequence that prevents us from becoming satiated on these beverages(18). However, for alcohol-containing beverages, the picture is far more complex than that for other beverages(34).

A large number of meta-analyses seem to confirm in free-living human subjects that adding sugar-sweetened beverages to the diet, increasing the amount consumed or replacing water or other non-energetic beverages with these beverages increases energy intake and weight(35-38). There are differences when these beverage studies have been funded by the beverage or sugar industries(35,39); however, a consensus has emerged that we do not compensate when we consume any caloric beverage and reducing the intake of these beverages via regulations and taxation has become a major public policy focus(40).

The reasons for concern with beverages with energy: the consumption perspective

The shift away from water and milk to an array of energetically sweetened, often caffeinated, drinks has occurred on a global level. We drink juices that are essentially water combined with one of many concentrates of fructose and some fruit flavorings. In Mexico, the USA, the UK and many major countries, energy from sugar-sweetened beverages and other energetic beverages increased to about 17–25% of total energy intake in all age groups(41-45). This is a transformation that has occurred over the last 2–3 decades and for some countries over just a few years. Consider some of the results of the changes underway:

Mexicans aged 2 years and older appear to have doubled their energy intake from beverages between 1999 and 2006 according to two national representative surveys that used somewhat different dietary intake methods(43,46,47).

Between 1989 and 2002 all US adults increased their intake of fluids by 21 ounces (612 ml). One hundred percent of these changes were in the form of sugar-sweetened beverages(48). Did they become more active and more dehydrated over this time or did marketing get them to just drink more?

School children in many countries across the globe in the period between 1990 and the present day have had water fountains removed from their schools and replaced by vending machines(13).

Results from national dietary intake surveys in the UK shows that all age groups consume over 17% if their energy intake from beverages and juices, alcohol and sugar-sweetened beverages represent key components of the diet of these individuals(41).

Sweetening of our food supply

Apart from sugar-sweetened beverages, there is surprisingly little documentation of the large proportion of processed foods that contain added sugar(16). Partly this is the result of our ability to keep up with the nutrient contents of the modern food supply. For example, there are over 1·3 million unique Universal Product Codes for food. In the US food composition table, we measure about 20–30 000 foods. For measurement of added sugar, the number is much less. We have very poor measures often of what is added sugar and total sugar. The US food composition table, despite being developed and updated to measure key shifts in composition of many basic foods, is just unable to measure or even systematically collect data on all these new foods(49). I have provided elsewhere with colleagues some rather indirect documentation of the increasing sugar use across the globe(16). The array of caloric sweeteners is in itself quite startling, but even more so is this subtle long-term shift in the content of our processed foods.

Animal source foods are subsidized to replace other components of our diet

Most of the increases in animal source food intake come from the low- and middle-income countries in this new millennia(50,51). However, over the post World War II period, the USA and the European Economic Union provided billions of dollars and euros of subsidy to reduce the costs of animal source foods (see section ‘Underlying major economic, marketing and social changes’)(13,52,53). From 1970 to 1994, on a global letter Delgado and other scholars from the International Food Policy Research Institute showed that global prices for 100 kg of beef declined from over $500 to under $200. Beef, pork and other animal source foods have very high price elasticities such that consumers are quite sensitive to price declines and increase significantly their purchases of these products(50,54). In addition, as income increases in low- and middle-income countries, a disproportionate increase in animal food consumption occurs(55,56).

Salt in our food supply abounds!

The issue of salt and its role in the global food supply is only recently coming under greater scrutiny(57-60). There are actually two camps of thought. There is one that states we need a certain amount of salt and if there is reduced salt in our food supply we might eat more food to obtain the same level of salt intake(61). The other side of the question is to assume that salt enhances appetite. There are dozens of home remedies and cookbooks based on the need to enhance appetite and use selected salts to assist. However, the science behind these assertions is lacking.

It is unclear how salt affects total food consumption and if it has a role in energy imbalance(60,62-68). A few scholars have speculated on a salt–soft drink linkage(69,70), an MSG-obesity linkage (MSG is a sodium salt of the non-essential amino acid glutamic acid)(71) and related a role of MSG in stimulating appetite and energy intake(72-74), and others but this is indeed a very understudied topic. One interesting study from the 1980s examined how a low-salt diet accompanied by an ad libitum salt shaker use would affect the total salt compensation but not overall food intake. This study found that there was no compensation(75). In a personal note, this same author argued it appears that salt consumption was remarkably stable across thousands of years but I do not know the basis for this assertion (Beauchamp, personal communication).

The major concern was the role of salt in hypertension and not obesity. Because of the role of salt in so many energy dense foods that are increasingly consumed as snacks, this is an important understudied topic(76,77).

Increasing frying of food and use of vegetable oils

The total fat intake is another area where our biology seems to clash with modern technology. The ability to taste fat could hold evolutionary advantages in the ability to absorb essential fatty acids from food(78-81). An argument was made that preferences for dietary fats are also either innate or learned in infancy of childhood(82). References to the desirable qualities of milk and honey (i.e. fat and sugar), cream, butter and animal fats are found throughout recorded history. All societies, irrespective of their income, price foods containing fat. Scientists have come to believe that physiological mechanisms that regulate fat intake are so imprecise that fat consumption is largely determined by the amount of fat available in the food supply(83,84). Another way to view the trend towards higher fat is the desire for a more diverse diet. Diets that incorporate meat and dairy products in addition to vegetables and grains tend to be higher in sugar and fat.

There was a large increase in the consumption of an array of vegetable-based oils and fats(85,86). Modern food technology provided the basis for cheap removal of corn, soyabean, cottonseed, rapeseed and dozens of other oils from their oilseed products. This was followed by plant breeding efforts to increase the oil content of all these plants and a revolution half a century ago in higher-income countries related to the use of vegetable oils. Across the globe, transfats were one component of this much larger shift, but in general what these reduced prices for vegetable oils has done is to have made it much cheaper for low-income households and poor countries to increase markedly their fat and oils intake. In Asia and the Middle East, the shifts were remarkable in terms of the consumption levels of vegetable oil of 1250–2100 kJ per individual. Frying of food is replacing baking, steaming and boiling in some countries(87-89).

Losing many healthful components: fibre, legumes, fruits and vegetables and coarse grains

There is much weaker documentation across the globe of the adverse changes in other components of the human diet. For selected countries, it was shown that legume, coarse grain and whole grain products, in general, were reduced in absolute and relative terms(90-94). The impact of these changes on health are clear; however, what they mean for obesity and energy imbalance is less understood and there is less consensus on that topic(12,95-101).

Cooking and eating behaviours: snacking up, eating events increased

We do not know a great deal about the effect of increased meal frequency on the total energy intake, weight dynamics, insulin resistance and lipid profile. The epidemiological literature is conflicting and often based on less than ideal study design(102-108). There is related literature on fasting and energy restriction suggesting potentially important benefits in terms of health and longevity(109,110), and a few studies suggest that frequent nibbling (defined as five or more times per day) has some health benefits, but this literature is small, conducted in diverse populations and lacks consensus(109-112). With respect to diabetes, there is an unofficial consensus in clinical care that consuming on evenly spaced eating occasions throughout the day is better than major binging episodes, but little formal research to back these recommendations.

A series of new papers of my group shows a major shift upwards in snacking and the total eating event behaviour in each of the last two decades(76,77,113-115). Other work in China has found a similar shift upwards in snacking(116,117).

In fact snacking and meal consumption are beginning to meld together and we might need to just discuss eating occasions in the future(113). The amount of eating has increased over the past 30 years among all ages in the USA to an average of over five for all those aged 2 years and older. The change from 1977 to 2006 was greatest for those in the 75th and 90th percentiles for both groups, although the mean number increased across all percentiles(113). Energy intake, particularly from snacking, increased for both children and adults at all percentiles of the distribution. Over this period, the time between the start of each eating occasion decreased by an hour for both children and adults (to 3·0 for children and 3·5 h for adults in 2003–6). Overwhelmingly, meals consisted of both foods and beverages, but the percent of snacking occasions in which only beverages were consumed increased considerably among children(76).

Underlying major economic, marketing and social changes

Economic changes, infrastructure, pricing and farm policies

Elsewhere I have written about the ways that farm policies, economic changes, shifts in transportation and other infrastructures and overall food price structures have affected dietary intake(13,55,56,118,119). We have created a food price structure that favours relatively animal source foods, sweets and fats. Furthermore, our infrastructure was designed in general around these same concerns.

Food distribution: supermarkets

Probably the most massive shift across the globe in terms of food supply in the last decade or two was the rise of supermarkets in all countries of the globe. Reardon and other economists have been documenting these shifts(120-126). Essentially they have shown that across all of Latin America, over 80% of all expenditures on food in cash and kind goes today for food purchased in supermarkets, that these changes have increased exponentially now across urban areas in Africa, all of the Middle East and most of Asia and the Caribbean and the Pacific.

There are many benefits: a safer food supply solving the cold chain for dairy and all meats, poultry, fish/seafood and produce. The costs are cheaper and the access to a ready to purchase food supply is much better. But there are costs: oils, highly processed, salty, sweet and fatty foods are cheaper and more plentiful. We do not understand yet the implications of these shifts as little has been done and the literature is anecdotal except for one cross-sectional paper(127).

Marketing, media

One of the least discussed and least understood areas of change affecting dietary and physical activity patterns is the role of the modern mass media in the low- and middle-income world(128). Throughout the developing world, there was a profound increase in the ownership of television (TV) sets, cell phones, computers and the penetration of modern media into the lives of all individuals. This was accompanied by a proliferation of modern magazines and ready access to DVDs of Western movies. Apart from higher-income countries, there is little documentation of the health effects of these changes. Examples from China are used to illustrate this set of changes. Many scholars accuse TV viewing as being directly responsible for child obesity, due both to its effect on energy expenditure as well as to the direct marketing of food on the TV and increased snacking(129,130). This remains to be studied in most developing countries in a rigorous causal manner. Similar increases in television ownership and viewership are noted throughout the developing world.

TV set ownership and modern TV programming are recent phenomena in China. In China, less than two-thirds (63%) of households owned a TV in 1989, and most (49%) owned a black and white set. By 2006, more than 99% of Chinese households owned a TV, with most (85%) owning a colour set.

Programming and advertisements were rapidly shifting towards more modern and Western content. For instance, the first TV advertisements began with one advertisement in 1979 on a Shanghai TV station and only began in earnest with a large increase in the 1990s. Today, China is considered the world’s fastest-growing advertising market(131).

Speed of change

We do not fully understand the role of each of these broad changes on the transformation of eating and movement. However, what is clear is the dietary changes that have occurred in a few countries like China in just a few years match earlier changes that occurred in Japan or South Korea in a decade or more(87). It took coca cola more than a century to achieve worldwide penetration of its products, whereas Red Bull did the same in 5 years. Today similar newly introduced products reach global markets much faster(13).

Body composition dynamics

Prevalence of overweight and obesity

There are over twenty larger countries with half of the adults overweight and obese and a large number of smaller islands that also fit in this category. At the upper level of overweight and obesity are the UK, Australia and the USA among high-income countries and Mexico, Egypt and South Africa among lower- and middle-income countries. Elsewhere I have provided detailed maps and data on overall patterns of overweight across the globe based on nationally representative samples(13,132-136).

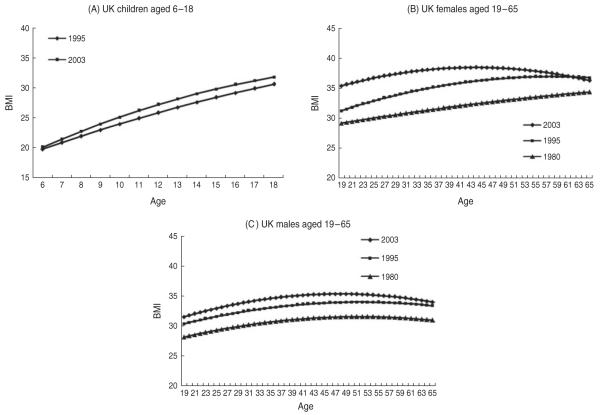

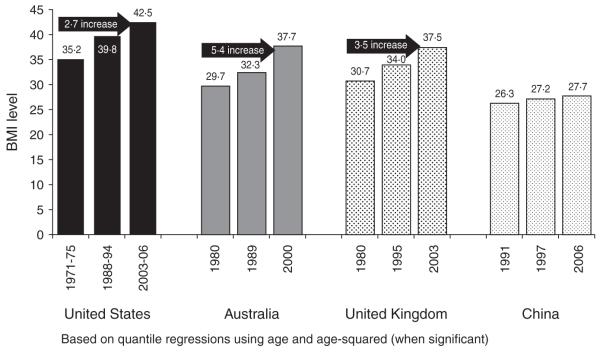

In the past, it has always been shown that the USA had the largest proportion of adults at the very high end with BMI above 40. This is changing. In a recent paper, I have shown that both Australian and UK women are shifting upwards the 95th centile mean BMI such that soon they will equal the USA(132). In Figs. 1 and 2, we present the basic data for the UK and then the differences between the USA, Australia and the UK.

Fig. 1.

Trends in the BMI level at the 95th centile in the UK.

Fig. 2.

The shift in BMI levels at the 95th centile for females aged 30.

Fig. 1 provides the three nationally representative surveys used for adults and the two available for children that had weight, height and demographic data. The National Heights and Weight Survey, 1980; The Dietary and Nutritional Survey of British, 1986–1987; The Health Survey for England, 1995 and 2003; The National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Adults aged 19–64 years, 2000–2001 were utilized. All the surveys were national representative, with multi-stage stratified random samples. In the survey of 1995 and 2003, data of children were available(137). The quantile regressions used to create at the 95th centile these age patterns are described in detail elsewhere (132). What we have found in the 1995–2003 period is a much greater increase in BMI for younger adult women than older ones in the UK.

In Fig. 2, we compare for the age of 30 the BMI across four countries. Among adults women display higher BMI levels for the 95th centile. Although the US women show much higher levels, the increase in the 1988–2006 18-year period in the 95th centile BMI level was only 2·7 BMI units for women aged 30. In contrast, the increases over much shorter periods in Australia of 1989–2000 11-year period (32·3–37·7) and the UK of 1995–2003 8-year period (34·0–37·5) were greater. Men in the UK did not display major increases in the 95th centile BMI.

Trends

It is very hard to create a clear picture of trends in child and adult overweight. A few countries have repeated nationally representative samples of all individuals aged 2 years and older where weight, height, age and date of birth are collected. The largest concentration of such surveys are for women of child-bearing age in the Demographic and Health Surveys of Demographic and Health Survey-Measure(133). We have also obtained for a number of lower- and higher-income countries nationally representative surveys of weight and height(134). We have two papers under review on this topic(135,136):

Across the low- and middle-income world adult over-weight prevalence is growing by about 0.·9–1·4 percentage points per year.

Across higher-income countries, the rate of growth for adults in overweight and obesity population prevalence points is about 0·8–1·0.

Across all countries, the rate of increase for child overweight and obesity using International Obesity Task Force standards is about 0·4–0·7 percentage points per year.

This means that we are seeing an increase in absolute numbers of a minimum of 67 million individuals each year right now. This is based on about 2·47 billion children and 5·4 billion adults in the world.

Shifts by social class

The general thinking for many years was that the burden of obesity and all other chronic diseases in higher-income countries was greater for low-income and low-education individuals, whereas for developing countries, it was the opposite, the rich bore the brunt of obesity(138). For low- and middle-income countries, this assertion was based on very little data. In the past decade, with many nationally representative cross-sectional surveys available for women and a few for men, more systematic research has taken place among both higher- and lower-income countries. The pattern for lower-income countries is becoming clearer with the burden shifting for women to the lower socioeconomic status groups but not for men(139-141). At the same time, in higher-income countries, in some cases the gap between rich and poor has widened and in others narrowed. Furthermore, these patterns do not hold for children and adolescents.

How do we proceed?

There are two global models for countries to take on the global obesity burden. One focuses on societal changes and the other on individual changes. I believe the UK is a global leader in the former approach and compare and contrast that with the US approach.

The UK and its Sociological Perspective

Although in the UK obesity prevention programmes of a large array have existed for a long time, the Foresight Obesity Project represented a milestone in national systematic efforts to produce a sustainable response to obesity(5-7). This systematic government effort began with quantitative modelling of the growth of obesity, the economic effect of this and the effect on the national health system(142). It then created a fairly complex systems-map of the causes of energy imbalance which laid out societal as well as individual causes of food consumption and activity. Out of this came a broad examination of all potential leverage points with weighting of the causal linkages. Of course, the new UK government might undo some of the initiatives underway with the previous government and move to a less confrontational more cooperative approach to the food and beverage industry.

Similar efforts were undertaken by the Institute of Medicine and others. The major difference was that the Foresight project was a government initiative and led directly to a vast dialogue with all the major stakeholders and policy-makers in the UK. A strong case was made for environmental changes necessary to support individual change. They created a goal of being the first major nation to reverse the rising tide of obesity. They also focused attention and action on the environmental causes.

While there is extensive decentralization in the UK and some efforts have only taken place in England, there were also systematic efforts underway across the entire UK. Actions taken provide some sense of the process and, significantly, funding that went with all activities and actions:

Vending machines banned in schools and drinking water promoted; schools record annual assessments of all activities and changes.

Advertisers banned from advertising to children and banned from advertising unhealthy foods in media.

Children aged 6 to 8 years are required to receive weekly cooking classes to learn about food, its preparation and handling.

Government accountability created across all agencies.

Set of initiatives and coalitions created, focused on Change4Life, Coalition for Better Health and the Healthy Food Code (e.g. traffic light system).

Power to restrict fast-food restaurants near schools and parks.

Project to provide fresh fruits and vegetables to small stores in deprived areas.

Putting in systematic surveillance and monitoring.

There were just so many more actions related to children. These began with midwife and nursery training, school workforce and nurse training, parent support advisers, training of school caterers, an array of people linked to supporting youth activity in and out of the schools, and many private sector activities. They continue to study causes and solutions and remain most active in addressing obesity across the life cycle. They did not see this as one action but a long series of actions, evaluations, studies and new actions.

United States and its Psychological Perspective

The Institute of Medicine and many others have discussed similar causal networks. Members of Congress have discussed the needs to regulate beverages and vending in the schools, and many other issues have been discussed. However, there has been no systematic approach that involves any environmental changes on any major levels. To date, here are some of the US actions:

Dozens of states have mandated more physical education classes, but only a few have provided funding (e.g. the state of Illinois has created fully funded mandates).

Neither state nor federal government has banned vending and promoted water.

No national or other media bans or controls exist as they relate to children.

Minimal federal funding has been linked with improved school nutrition.

A number of state and local governments have implemented subsidies to provide supermarkets to food deserts (namely communities with limited access to affordable, healthy food); however, the research backing these activities is limited.

One or two municipalities have supported providing education and improved facilities and food supplies to food stores in poor areas.

Sustainable agriculture, promoted by upper-class intellectuals, has led to major funding for an unproven area of fresh open farmers markets for the poor; the government has jumped into this also.

Many US actions were based on politics without proven success, others were taken and done with minimal funding, and there is no systematic attack on any age group or across the life cycle. On the other hand, the media has repeatedly reported on a few issues such as sugar-sweetened beverages and the beverage industry has shifted to marketing ‘healthy function sugar-sweetened waters, etc.,’ as well as juices to counter this. Again unlike the systematic banning of vending in schools in the UK, even the US Institute of Medicine reports and analyses focus on allowing some sugary beverages but just limiting them.

Finally, the environment in the USA has not changed amid a decade of discussion about child obesity; only rather small, unsystematic efforts have been established. This campaign is unlike decades of work which got the USA to see seat belt regulations, fluoridation and tobacco prevention solutions as societal issues that require regulations, taxes and very systematic efforts(143). Michelle Obama is leading an effort to place greater emphasis on prevention of child obesity; however, all efforts are based on a model of cooperation with minimal focus on legislative and other larger-scale regulatory options. The author feels if history taught us any lessons from some of these successful public health campaigns, a combination of taxation, regulation and norm changes are needed to successfully address the issue of obesity prevention in the modern world.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health (R01-HD30880, DK056350 and R01-HD38700). The author thanks Frances Dancy for administrative support.

Abbreviations

- TV

television

Footnotes

The Summer Meeting of the Nutrition Society hosted by the Scottish Section was held at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh on 28 June–1 July 2010

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Monda KL, Adair LS, Zhai F. Longitudinal relationships between occupational and domestic physical activity patterns and body weight in China. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;62:1318–1325. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell AC, Ge K, Popkin BM. Weight gain and its predictors in Chinese adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1079–1086. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell AC, Ge K, Popkin BM. The road to obesity or the path to prevention: motorized transportation and obesity in China. Obes Res. 2002;10:277–283. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng SW, Norton EC, Popkin BM. Why have physical activity levels declined among Chinese adults? Findings from the 1991–2006 China health and nutrition surveys. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1305–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King D. Foresight report on obesity. Lancet. 2007;370:1754. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61739-5. author reply 1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopelman P. Symposium 1: Overnutrition: consequences and solutions Foresight Report: the obesity challenge ahead. Proc Nutr Soc. 2009;69(1):80–85. doi: 10.1017/S0029665109991686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McPherson K, Marsh T, Brown M. Foresight report on obesity. Lancet. 2007;370:1755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61740-1. author reply 1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine. National Research Council . The Public Health Effects of Food Deserts: Workshop Summary. Institute of Medicine, National Research Council; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Time Use Survey . Percent of the Population Engaging in Selected Activities by Time of Day. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Washington DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monteiro CA, Gomes FS, Cannon G. The snack attack. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:975–981. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.187666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WCRF/AICR . Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Popkin BM. The World Is Fat – The Fads, Trends, Policies, and Products That Are Fattening the Human Race. Avery-Penguin Group; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monteiro CA. Nutrition and Health. The issue is not food, nor nutrients, so much as processing. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:729–731. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009005291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Popkin BM, D’Anci KE, Rosenberg IH. Water, hydration and health. Nutr Rev. 2010;68:439–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popkin BM, Nielsen SJ. The sweetening of the world’s diet. Obes Res. 2003;11:1325–1332. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popkin BM. Global nutrition dynamics: the world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:289–298. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolf A, Bray GA, Popkin BM. A short history of beverages and how our body treats them. Obes Rev. 2008;9:151–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mourao D, Bressan J, Campbell W. Effects of food form on appetite and energy intake in lean and obese young adults. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1688–1695. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattes R. Fluid calories and energy balance: the good, the bad, and the uncertain. Physiol Behav. 2006;89:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiMeglio DP, Mattes RD. Liquid versus solid carbohydrate: effects on food intake and body weight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:794–800. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mattes R. Dietary compensation by humans for supplemental energy provided as ethanol or carbohydrate in fluids. Physiol Behav. 1996;59:179–187. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raben A, Vasilaras TH, Moller AC. Sucrose compared with artificial sweeteners: different effects on ad libitum food intake and body weight after 10 wk of supplementation in overweight subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:721–729. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.4.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Castro J. The effects of the spontaneous ingestion of particular foods or beverages on the meal pattern and overall nutrient intake of humans. Physiol Behav. 1993;53:1133–1144. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90370-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Wymelbeke V, Beridot-Therond ME, Gueronniere V. Influence of repeated consumption of beverages containing sucrose or intense sweeteners on food intake. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:154–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavin JH, French SJ, Ruxton CH. An investigation of the role of oro-sensory stimulation in sugar satiety? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:384–388. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hagg A, Jacobson T, Nordlund G. Effects of milk or water on lunch intake in preschool children. Appetite. 1998;31:83–92. doi: 10.1006/appe.1997.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beridot-Therond ME, Arts I, Fantino M. Short-term effects of the flavour of drinks on ingestive behaviours in man. Appetite. 1998;31:67–81. doi: 10.1006/appe.1997.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poppitt SD, Eckhardt JW, McGonagle J. Short-term effects of alcohol consumption on appetite and energy intake. Physiol Behav. 1996;60:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(96)00159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DellaValle DM, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Does the consumption of caloric and non-caloric beverages with a meal affect energy intake? Appetite. 2005;44:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tordoff MG, Alleva AM. Effect of drinking soda sweetened with aspartame or high-fructose corn syrup on food intake and body weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51:963–969. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.6.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flood J, Roe L, Rolls B. The effect of increased beverage portion size on energy intake at a meal. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:1984–1990. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mattes RD. Fluid energy-where’s the problem? J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:1956–1961. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeomans MR. Alcohol, appetite and energy balance: is alcohol intake a risk factor for obesity? Physiol Behav. 2010;100:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vartanian L, Schwartz M, Brownell K. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:667–675. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Osganian SK. Effects of decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption on body weight in adolescents: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Pediatric. 2006;117:673–680. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:274–288. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, et al. Sugar sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010 doi: 10.2337/dc10-1079. In the Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lesser LI, Ebbeling CB, Goozner M. Relationship between funding source and conclusion among nutrition-related scientific articles. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brownell K, Farley T, Willett W. The public health and revenue generating benefits of taxing sugar sweetened beverages. New Engl J Med. 2009;360:1805–1808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0905723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Popkin BM, Ng SW, Mhurchu CN, Jebb S. Beverage Patterns and Trends in the United Kingdom. University of North Carolina; Chapel Hill, NC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barquera S, Hernández L, Tolentino ML. Energy from beverages is on the rise among Mexican adolescents and adults. J Nutr. 2008;138:2454–2461. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.092163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rivera JAM-HO, Rosas-Peralta M, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Popkin BM, Willett WC. Consumo de bebidas y prevención de la obesidad. Salud Publica Mex. 2008;50:173–195. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342008000200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanigorski AM, Bell AC, Swinburn BA. Association of key foods and beverages with obesity in Australian schoolchildren. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:152–157. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007246634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muckelbauer R, Libuda L, Clausen K. Promotion and provision of drinking water in schools for overweight prevention: randomized, controlled cluster trial. Pediatric. 2009;123:e661–e667. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barquera S, Campirano F, Bonvecchio A, et al. Caloric beverage consumption patterns in Mexican children. J Nutr. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-47. In the Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barquera S, Hernandez-Barrera L, Tolentino ML. Energy intake from beverages is increasing among Mexican adolescents and adults. J Nutr. 2008;138:2454–2461. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.092163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duffey K, Popkin BM. Shifts in patterns and consumption of beverages between 1965 and 2002. Obesity. 2007;15:2739–2747. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Slining M, Popkin BM. How do we determine and measure junk foods (Foods with minimal nutritional value)? Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina; 2010. unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Delgado CL. Rising consumption of meat and milk in developing countries has created a new food revolution. J Nutr. 2003;133:3907S–3910S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3907S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delgado CL, Rosegrant MW, Meijer S. Livestock to 2020: the revolution continues; Paper presented at the Annual Meetings of the International Agricultural Trade Research Consortium (IATRC); Auckland, New Zealand. 18–19 January 2001.2001. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gardner BL. American Agriculture in the Twentieth Century: How it Flourished and What it Cost. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Starmer E, Witteman A, Wise TA. Feeding the Factory Farm: Implicit Subsidies to the Broiler Chicken Industry. 2006 GDAE Working Paper 2006 [cited 12 March 2007]. Available from: http://ideas.repec.org/p/dae/daepap/06-03.html.

- 54.Guo X, Popkin BM, Mroz TA. Food price policy can favorably alter macronutrient intake in China. J Nutr. 1999;129:994–1001. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.5.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guo XG, Mroz TA, Popkin BM. Structural change in the impact of income on food consumption in China, 1989–1993. Econ Dev Cult Change. 2000;48:737–760. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Du S, Mroz TA, Zhai F. Rapid income growth adversely affects diet quality in China-particularly for the poor! Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1505–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elliott P, Brown I. Sodium intakes around the world: background; Document prepared for the Forum and Technical Meeting on Reducing Salt Intake in Populations; Paris. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 58.He FJ, MacGregor GA. A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:363–384. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow GM, Coxson PG. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:590–599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Institute of Medicine Food and Nutrition Board . Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake in the United States. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Geerling JC, Loewy AD. Central regulation of sodium appetite. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:177–209. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.039891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mattes RD. The taste for salt in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:692S–697S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.2.692S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.The China Salt Substitute Study Collaborative Group Salt substitution: a low-cost strategy for blood pressure control among rural Chinese. A randomized, controlled trial. J Hypertens. 2007;25:2011–2018. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282b9714b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meneton P, Jeunemaitre X, de Wardener HE. Links between dietary salt intake, renal salt handling, blood pressure, and cardiovascular diseases. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:679–715. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00056.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beauchamp GK, Moran M. Acceptance of sweet and salty tastes in 2-year-old children. Appetite. 1984;5:291–305. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(84)80002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Desor JGL, Maller O. Preferences for sweet and salty in 9- to 15-year-old and adult humans. Science. 1975;190:686–687. doi: 10.1126/science.1188365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Contreras RJ. Salt appetite. Science. 1983;219:1419. doi: 10.1126/science.219.4591.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sakai RR. The future of research on thirst and salt appetite. Appetite. 2004;42:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2002.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gibson S. Salt intake is related to soft drink consumption in children and adolescents: a link to obesity? Hypertension. 2008;51:e54. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.112763. author reply e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.He FJ, Marrero NM, MacGregor GA. Salt intake is related to soft drink consumption in children and adolescents: a link to obesity? Hypertension. 2008;51:629–634. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.100990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.He K, Zhao L, Daviglus ML. Association of monosodium glutamate intake with overweight in Chinese adults: the INTERMAP Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1875–1880. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cox DN, Perry L, Moore PB. Sensory and hedonic associations with macronutrient and energy intakes of lean and obese consumers. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:403–410. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Maffeis C, Grezzani A, Perrone L. Could the savory taste of snacks be a further risk factor for overweight in children? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:429–437. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318163b850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bellisle F, Monneuse MO, Chabert M. Monosodium glutamate as a palatability enhancer in the European diet. Physiol Behav. 1991;49:869–873. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90196-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Beauchamp GK, Bertino M, Engelman K. Failure to compensate decreased dietary sodium with increased table salt usage. JAMA. 1987;258:3275–3278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Piernas C, Popkin BM. Trends in snacking among U.S. children. Health Affairs. 2010;29:398–404. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Piernas C, Popkin BM. Snacking increased among U.S. adults between 1977 and 2006. J Nutr. 2010;140:325–332. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Caputo FA, Mattes RD. Human dietary responses to perceived manipulation of fat content in a midday meal. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1993;17:237–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mattes RD. Fat taste and lipid metabolism in humans. Physiol Behav. 2005;86:691–697. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lermer CM, Mattes RD. Perception of dietary fat: ingestive and metabolic implications. Prog Lipid Res. 1999;38:117–128. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(98)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mattes RD. Oral fat exposure alters postprandial lipid metabolism in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63:911–917. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.6.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Drewnowski A. Sensory preferences for fat and sugar in adolescence and adult life. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1989;561:243–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb20986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Drewnowski A, Kurth CL, Rahaim JE. Taste preferences in human obesity: environmental and familial factors. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:635–641. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Drewnowski A, Krahn D, Demitrack M. Taste responses and preferences for sweet high-fat foods: evidence for opioid involvement. Physiol Behav. 1992;51:371–379. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90155-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Popkin B, Drewnowski A. Dietary fats and the nutrition transition: new trends in the global diet. Nutr Rev. 1997;55:31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Drewnowski A, Popkin BM. The nutrition transition: new trends in the global diet. Nutr Rev. 1997;55:31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Popkin BM, Lu B, Zhai F. Understanding the nutrition transition: measuring rapid dietary changes in transitional countries. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:947–953. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Popkin BM. Global changes in diet and activity patterns as drivers of the nutrition transition. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program. 2009;63:1–10. doi: 10.1159/000209967. discussion 10–14, 259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang Z, Zhai F, Du S. Dynamic shifts in Chinese eating behaviors. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Popkin BM, Keyou G, Zhai F. The nutrition transition in China: a cross-sectional analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1993;47:333–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Du S, Lu B, Zhai F. A new stage of the nutrition transition in China. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:169–174. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Du S, Lu B, Zhai F. The nutrition transition in China: a new stage of the Chinese diet. In: Caballero B, Popkin B, editors. The Nutrition Transition: Diet and Disease in the Developing World. Academic Press; London: 2002. pp. 205–222. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Popkin BM, Horton S, Kim S. The nutrition transition and prevention of diet-related chronic diseases in Asia and the Pacific. Food Nutr Bull. 2001;22:1–58. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Popkin BM, Horton S, Kim S. Trends in diet, nutritional status, and diet-related noncommunicable diseases in China and India: the economic costs of the nutrition transition. Nutr Rev. 2001;59:379–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2001.tb06967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Montonen J, Knekt P, Jarvinen R. Whole-grain and fiber intake and the incidence of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:622–629. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.3.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Holmes MD, Liu S, Hankinson SE. Dietary carbohydrates, fiber, and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:732–739. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pereira MA, O’Reilly E, Augustsson K. Dietary fiber and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:370–376. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.4.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schulze MB, Liu S, Rimm EB. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and dietary fiber intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes in younger and middle-aged women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:348–356. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Burkitt DP. Some diseases characteristic of modern Western civilization. Br Med J. 1973;1:274–278. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5848.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu S, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ. Whole grain consumption and risk of ischemic stroke in women: A prospective study. JAMA. 2000;284:1534–1540. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jacobs DR, Jr, Gallaher DD. Whole grain intake and cardiovascular disease: a review. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2004;6:415–423. doi: 10.1007/s11883-004-0081-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bellisle F, Le Magnen J. The structure of meals in humans: eating and drinking patterns in lean and obese subjects. Physiol Behav. 1981;27:649–658. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bellisle F, McDevitt R, Prentice AM. Meal frequency and energy balance. Br J Nutr. 1997;77(Suppl 1):S57–70. doi: 10.1079/bjn19970104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Carlson O, Martin B, Stote KS. Impact of reduced meal frequency without caloric restriction on glucose regulation in healthy, normal-weight middle-aged men and women. Metabolism. 2007;56:1729–1734. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Solomon T, Chambers E, Jeukendrup A. The effect of feeding frequency on insulin and ghrelin responses in human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2008;100:810–819. doi: 10.1017/S000711450896757X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kerver JM, Yang EJ, Obayashi S. Meal and snack patterns are associated with dietary intake of energy and nutrients in US adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kant AK, Schatzkin A, Graubard BI. Frequency of eating occasions and weight change in the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:468–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ma Y, Bertone ER, Stanek EJ., III Association between eating patterns and obesity in a free-living US adult population. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:85–92. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Farshchi HR, Taylor MA, Macdonald IA. Beneficial metabolic effects of regular meal frequency on dietary thermogenesis, insulin sensitivity, and fasting lipid profiles in healthy obese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:16–24. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Heilbronn LK, Smith SR, Martin CK. Alternate-day fasting in nonobese subjects: effects on body weight, body composition, and energy metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:69–73. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jenkins DJ, Ocana A, Jenkins AL. Metabolic advantages of spreading the nutrient load: effects of increased meal frequency in non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55:461–467. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.2.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM, Vuksan V. Nibbling versus gorging: metabolic advantages of increased meal frequency. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:929–934. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198910053211403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Popkin BM, Duffey KJ. Does hunger and satiety drive eating anymore? Increasing eating occasions and decreasing time between eating occasions in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1342–1347. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wansink B. Mindless Eating – Why We Eat More Than We Think. Bantam-Dell; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wansink B. Snack attack? Don’t be tricked by low fat labels It’s easy to overeat when you think treats are ‘good’ for you. 2007 [cited 9 March]. Available from: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/17469445/

- 116.Wang Z, Zhai F, Du S. Snacking trends in China. 2010 In the Press. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wang Z, Zhai F, Shufa D. Dynamic shifts in Chinese eating behaviors. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Popkin BM. Technology, transport, globalization and the nutrition transition. Food Policy. 2006;31:554–569. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Popkin BM, Ng SW. The nutrition transition in high and low-income countries: what are the policy lessons? In: Otsuka K, Kalirajan K, editors. Contributions of Agricultural Economics to Critical Policy Issues. Blackwell Synergy; Malden, MA and Oxford, UK: 2008. pp. 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Minten B, Reardon T. Food prices, quality, and quality’s pricing in supermarkets versus traditional markets in developing countries. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2008;30:480–490. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stunkard AJ, Allison KC, O’Reardon JP. The night eating syndrome: a progress report. Appetite. 2005;45:182–186. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Reardon T, Timmer P, Berdegue J. The rapid rise of supermarkets in developing countries: induced organizational, institutional, and technological change in agrifood systems. Electron J Agr Dev Econ. 2004;1:168–183. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hu D, Reardon T, Rozelle S. The emergence of supermarkets with Chinese characteristics: challenges and opportunities for China’s agricultural development. Dev Policy Rev. 2004;22:557–586. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Reardon T, Timmer CP, Barrett CB. The rise of supermarkets in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Am J Agr Econ. 2003;85:1140–1146. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Balsevich F, Berdegue JA, Flores L. Supermarkets and produce quality and safety standards in Latin America. Am J Agr Econ. 2003;85:1147–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Reardon T, Berdegué J. The rapid rise of supermarkets in Latin America: challenges and opportunities for development. Dev Policy Rev. 2002;20:371–388. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Asfaw A. Supermarket Expansion and the Dietary Practices of Households: Some Empirical Evidence from Guatemala. International Food Policy Research Institute; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 128.International Broadcasting Audience Research . World Radio and Television Receivers International Broadcasting Audience Research Library. BBC World Service; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Jackson DM, Djafarian K, Stewart J. Increased television viewing is associated with elevated body fatness but not with lower total energy expenditure in children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1031–1036. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Robinson TN. Television viewing and childhood obesity. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48:1017–1025. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Weber IG. Challenges facing China’s television advertising industry in the age of spiritual civilization: an industry analysis. Int J Advert. 2000:259–281. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Popkin BM. Recent dynamics suggest selected countries catching up to US obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:284S–288S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28473C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Mendez MA, Monteiro CA, Popkin BM. Overweight exceeds underweight among women in most developing countries. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:714–721. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.3.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Popkin BM, Conde W, Hou N. Is there a lag globally in overweight trends for children compared with adults? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1846–1853. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Jones-Smith J, Gordon-Larsen P, Siddiqi A. Time trends among women in 41 low- and middle-income countries (1991–2007) Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina; 2010. Is the burden of overweight shifting to the poor across the globe? unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ng SW, Jones-Smith J, Popkin BM. Rising global obesity is reaching the rural areas quickly: a 43-country time trends study. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina; 2010. unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Stamatakis E, Primatesta P, Chinn S. Overweight and obesity trends from 1974 to 2003 in English children: what is the role of socioeconomic factors? Arch Dis Childhood. 2005;90:999–1004. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.068932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Sobal J, Stunkard AJ. Socioeconomic status and obesity: a review of the literature. Psychol Bull. 1989;105:260–275. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Monteiro CA, Conde WL, Lu B. Obesity and inequities in health in the developing world. Int J Obes Relat Metabol Disord. 2004;28:1181–1186. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Monteiro CA, Moura EC, Conde WL. Socioeconomic status and obesity in adult populations of developing countries: a review. Bull World Health Org. 2004;82:940–946. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Monteiro CA, Conde WL, Popkin BM. Income-specific trends in obesity in Brazil: 1975–2003. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1808–1812. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Foresight . Tackling Obesities: Future Choices-Project Report. 2nd ed. UK Government Office for Science; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Brownell KD, Warner KE. The perils of ignoring history: big tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is big food? Milbank Q. 2009;87:259–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]