Abstract

A 34-year-old female presented with anorectal pain and rectal bleeding due to an extensive rectal tumour. A trephine loop ileostomy was fashioned and biopsies were initially reported to show a poorly differentiated cloacogenic carcinoma. CT revealed numerous liver metastases. A histological review and immunohistochemical studies subsequently favoured a primitive neuroectodermal tumour (PNET). Stem-cell supported chemoradiotherapy resulted in complete resolution of her primary tumour and liver metastases. Serial CT scanning and endoscopy revealed no recurrence after 7 years of follow-up, when she presented with a malignant anal fissure. Imaging and subsequently abdominoperineal resection revealed no evidence of metastases from either the anal cancer or the PNET tumour. Histopathology showed a T1N0R0 basaloid squamous carcinoma originating from grade III squamous intraepithelial neoplasia with no obvious wart viral infection.

BACKGROUND

Ewing’s sarcoma is a rare soft tissue variant of Ewing’s osteosarcoma first reported in 1969.1,2 The term primitive neuroectodermal tumour (PNET) was coined by Hart et al to describe small round and undifferentiated cells that resemble cells derived from embryonic neural tube, and now termed central PNET, which can arise in the brain or spinal cord.3,4 Conversely, peripheral PNET is derived from neural crest cells and is found in soft tissues and bones.4,5 Osseous or bone Ewing’s sarcoma (OES), extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma (EOE), PNET and Askin’s tumour are all members of small round cell sarcoma family known as the Ewing’s sarcoma family (ESF) and characterised by their cytogenetic and immunohistochemical similarities.6 PNETs demonstrate neuroectodermal differentiation with Homer–Wright rosettes, not found in other ESF members.6 The importance of this case is that this patient is believed to be the first recorded long-term survivor, in remission 7 years following intensive chemoradiotherapy and stem cell transplant, for metastatic PNET/Ewing’s type sarcoma of the rectum, but complicated by the development of anal carcinoma.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 34-year-old female presented in 2001 with a 3-month history of anorectal and left sciatic pain, rectal bleeding, mucus discharge, tenesmus and difficulty in defecation and micturition. Examination revealed a large, fixed posterior ulcerating tumour extending from the mid-anal canal 10 cm proximally into the rectum. A trephine loop ileostomy was fashioned.

INVESTIGATIONS

CT revealed multiple (>30) liver metastases and extensive pelvic spread.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Biopsies were initially reported as poorly differentiated cloacogenic carcinoma. She commenced continuous infusion fluorouracil and oxaliplatin 3 weekly with concomitant radiotherapy 4500 cGY in 25 fractions in January 2002. On completion of three cycles CT showed a partial response in the pelvic disease but no change in the liver metastases.

TREATMENT

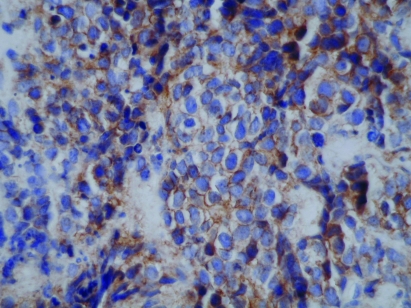

Subsequent histological review indicated that the diagnosis was more consistent with a PNET arising from the anal canal with liver metastases rather than a carcinoma. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrated cytokeratin expression in dots next to the nuclei, focal staining for P-glycoprotein 9.5 and uniform membrane staining for CD99 (MIC2) (figs 1–3). A sarcoma type chemotherapeutic regimen was given using IVAD (ifosfamide 5000 mg/m2 intravenous over 3 days, vincristine 2 mg intravenous day 1, and doxorubicin 20 mg/m2 intravenous days 1–3, with mesna support, granisetron and dexamethasone) as an inpatient for five cycles every 3 weeks from May to July 2002. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor was given to minimise bone marrow suppression. An excellent response resulted in resolution of liver metastases and marked improvement in the pelvic disease. The response was consolidated with peripheral blood stem cell supported high-dose chemotherapy in August 2002 with carboplatin at a dose calculated to give an area under the curve (AUC) of 15 intravenous, etoposide 100 mg/m2 intravenous twice daily ×4 and melphalan 140 mg/m2 intravenous. This required intensive inpatient support during a prolonged 2–3 week period of bone marrow suppression. Recovery was complicated by the need for intravenous antibiotics, blood and platelet support. Toxicities included temporary alopecia, nausea, vomiting, neuropathy, tiredness and bone marrow suppression followed by a complete recovery from all chemotherapy-related side effects. The patient’s ileostomy was reversed in 2003.

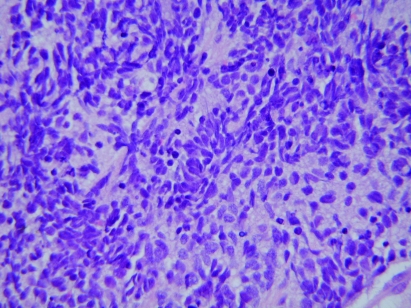

Figure 1.

Ewing’s sarcoma: small cells with dark blue staining nucleus and indistinct cell border (×400).

Figure 3.

Ewing’s tumour CD99 showing membrane staining of many tumour cells (×400).

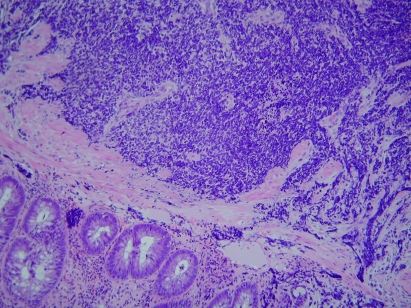

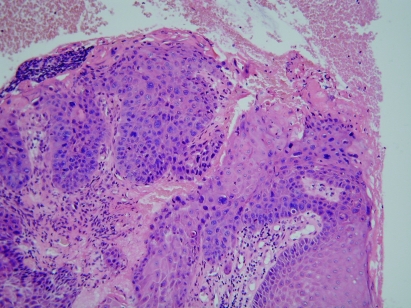

Figure 2.

The darkly staining tumour cells can be seen beneath the rectal mucosa (×100).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

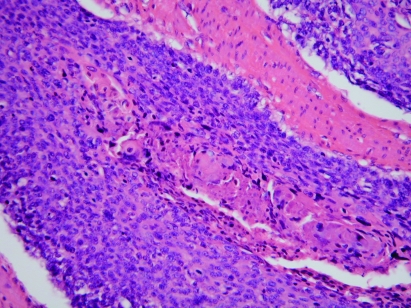

There was a complete response with no requirement for further anticancer treatment. Anorectal function remained good; urge incontinence was controlled satisfactorily with loperamide and reduction of dietary fibre. Serial CT scans, clinical examination and endoscopy confirmed complete remission 7 years after treatment. She then presented with a malignant posterior anal fissure. Imaging with CT and MRI revealed no evidence of metastatic disease from either the PNET tumour or the anal cancer. In view of previous chemoradiotherapy, an abdominoperineal resection was performed uneventfully without further neoadjuvant therapy. Histopathology showed a pT1N0R0 poorly differentiated basaloid squamous carcinoma originating from grade III squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN III) at the anorectal junction/dentate line zone in the posterolateral anal canal. While some keratinisation and multinucleate cells were seen raising the possibility of human papillomavirus (HPV), no definite koilocytosis was present. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated diffuse cytoplasmic cytokeratin staining unlike the PNET tumour, though it did show membrane CD99 staining (figs 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Basaloid carcinoma of anus (×200).

Figure 5.

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia near the basaloid carcinoma (×200).

Fluorescence in situ hybridisation analysis of interphase nuclei from a paraffin section showed no evidence of an EWSR1 arrangement either in the initial PNET or the subsequent basaloid carcinoma, though there were extra copies of this gene in the basaloid tumour.

DISCUSSION

PNET/Ewing’s type sarcoma is most prevalent in the first and second decades of life at a median age of 15 years, with a slight male predominance.6,7 It accounts for 3–4% of childhood and adolescent cancers with an incidence of 1.7–2.1 per million.8,9 Although children and young adults are most commonly affected, it can occur at any age.8,10 Primary EOE sarcoma occurs most commonly in the trunk, extremities, head and neck, and retroperitoneum.7 Other sites include the kidneys, parotid glands, larynx, chest wall, lungs, myocardium, diaphragm, gall bladder, spinal epidural space, abdominal wall, rectovaginal septum, vagina, uterus, cervix, ovaries, oesophagus, jejunum, ileum, common hepatic duct and head of the pancreas.9,11–16

Tissue diagnosis is difficult, exemplified by this case, due to a resemblance to other tumour types, including carcinoma, lymphoma, melanoma, synovial sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma.6,12 Ewing’s sarcoma is confirmed by the demonstration of a typical chromosomal translocation t(11;22) (q24:12) and its variants.4,11,12,17 Histologically, there are small round blue cells without a distinct cell border.12,17 Immunohistochemically, cellular membranes mostly stain in a strong Olympic-ring-like pattern due to high expression of the cell surface membrane protein p30/32 or CD99 antigen (encoded by the MIC2 gene) (figs 1–3).4,6,11,12,18 Although CD99 membrane stains positive in other tumours, most of these are not small round cell tumour types. Cytoplasmic staining is non-specific.6 Recent evidence suggests that about 75% of patients present with localised disease and that 70–80% are curable with combined treatment modalities of chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery.6,8 The cure rate for those with metastatic disease is 15–30%.8,18 To our knowledge, there are only two previous reports of EOE involving the rectum.

Drut et al12 reported a 17-year-old male who presented with massive rectal bleeding and pain from an 8×6 cm rectal polyp that autoamputated, with immediate symptom relief. Imaging showed no evidence of metastases. Biopsies of the polyp base confirmed residual tumour. Following a complete response to chemotherapy (vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, iphosphamide and etoposide), he was in remission 1 year later.

Vardy et al17 reported a 53-year-old male presenting with bleeding and heaviness due to a rectal tumour, treated by low anterior resection. Histopathological and immunohistochemical studies supported a diagnosis of EOE. There was no evidence of metastatic disease. Following an initial response from pelvic radiotherapy and four cycles of chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and doxorubicin), he died 2 years later from pulmonary and cerebral metastases.

Our patient is unique as the only known long-term survivor, after chemoradiotherapy and stem cell transplant without any form of radical surgery, for Ewing’s/PNET anorectal sarcoma, despite the presence of locally extensive and fixed disease at presentation. Her quality of life has remained excellent, with good bowel function, and urgency as her only symptom until her recent presentation with an anal fissure due to a pT1N0R0 basaloid squamous carcinoma treated by abdominoperineal resection. No adjuvant treatment is planned. The presence of recurrent PNET sarcoma has been excluded by imaging and negative laparotomy. It is unlikely that radiotherapy induced the new squamous carcinoma after a relatively short interval. The reason for its origin remains unclear, but a range of tumours can occur after bone marrow transplantation and associated therapies due to immune suppression. HPV infection remains a possibility, although no morphological evidence of HPV activity was found. It is reasonable to question the appropriateness of the diagnosis of PNET, particularly as subsequent interphase cytogenetic investigation failed to show the typical EWSR1 gene rearrangement, and the demonstration of membrane CD99 on the original tumour and the later basaloid carcinoma. However, the morphology and pattern of cytokeratin expression are different, and the response to chemotherapy (which is the point of the diagnostic exercise) also seems to justify the diagnosis.

LEARNING POINTS

Ewing’s/primitive neuroectodermal tumour mainly affects young age groups.

Histopathologically, it may be confused with other tumour types.

It is associated with chromosomal translocation t(11:22) (q24:12), and typical immunohistochemical features.

It should be considered a potentially curable systemic disease from the outset, requiring aggressive local and systemic sarcoma-specific treatment with peripheral stem cell supported chemoradiotherapy, with surgical resection if operable.

It requires vigilance about the long-term risk of a second neoplasm after bone marrow transplantation and associated therapies.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tefft M, Vawter G, Mitus A. Paravertebral “round cell” tumours in children. Radiology 1969; 92: 1501–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angervall L, Enzinger FM. Extraskeletal neoplasm resembling Ewing’s Sarcoma. Cancer 1975; 36: 240–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hart M, Earle K. Primitive neuroectodermal tumours of the brain in children. Cancer 1973; 32: 890–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mobley B, Roulston D, Shah G, et al. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor/Ewing’s sarcoma of the craniospinal vault: case reports and review. Hum Pathol 2006; 37: 845–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park J, Lee S, Kang H, et al. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma-primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the uterus: A case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol 2007; 106: 427–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodis L, Bennett M. Ewing’s Sarcoma metastasis to the gastric wall in a 72-year-old patient. MedGenMed 2006; 8: 6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Cancer Institute Ewing family of tumors treatment (PDQ). http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/ewings/Healthprofessional (accessed 11 June 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Cancer Institute Cancer treatment and prevention: overview of the Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors. http://patient.cancerconsultants.com/CancerTreatment_Ewings_Sarcoma.aspx?DocumentId=39399 (accessed 11 June 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaspers G, Kamphorst W, van de Graaff M, et al. Primary spinal epidural extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma. Cancer 1991; 68: 648–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung C, Kandel R, Bell R, et al. Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma in a 77-year-old woman. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2001; 125: 1358–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayakumar S, Power D. Ewing’s sarcoma/PNET: a histopathological review. Internet J Orthop Surg 2006; 3 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drut R, Drut M, Muller C, et al. Rectal primitive neuroectodermal tumor. Pediatr Pathol Mol Med 2003; 22: 391–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aydinli B, Ozturk G, Yildirgan M, et al. Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma in the abdominal wall: A case report. Acta Oncol 2006; 45: 484–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petkovic M, Zamolo G, Muhvic D, et al. The first report of extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma in the rectovaginal septum. Tumori 2002; 88: 345–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thebert A, Francis I, Bowerman R. Retroperitoneal extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma with renal involvement: US and MRI Findings. Clin Imaging 1993; 17: 149–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eroglu A, Kurkcuoglu I, Karaoglanoglu N, et al. Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma of the diaphragm presenting with haemothorax. Ann Thorac Surg 2004; 78: 715–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vardy J, Joshua AM, Clarke SJ, et al. Small blue cell tumour of the rectum, Case 1: Ewing’s sarcoma of the rectum. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 910–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Institute Ewing’s sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor. http://cancerweb.ncl.ac.uk/cancernet/100021.html (accessed 11 June 2009) [Google Scholar]