Abstract

Infliximab has become increasingly important in the treatment of SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) syndrome. There is, however, little experience with this biological agent, and treatment protocols usually follow the regimens for spondylarthropathies. We report a patient with a highly unusual and severe clinical presentation of SAPHO syndrome including widespread bone and skin disease, and collagenous colitis. Infliximab treatment (5 mg/kg) given at weeks 0, 2 and 6 and every 8 weeks thereafter, induced rapid remission of the osteoarticular symptoms, although the skin lesions improved only partially, and after 10 months continuous therapy with infliximab a bone scan even uncovered new active bone lesions. Collagenous colitis is unresponsive to tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) blocking agents. This moderate response to infliximab may indicate that a more aggressive treatment protocol is mandatory. We further believe that remission of osteoarticular complaints should be routinely confirmed by scintigraphic findings to verify treatment response.

BACKGROUND

SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) syndrome is characterised by multifaceted skeletal manifestations including recurrent multifocal osteitis, hyperostosis and synovitis, which are most likely to involve the anterior chest wall including the clavicle, although the lower ribs, pelvis, and any part of the axial and appendicular skeleton may be affected.1 Skin lesions include pustulosis, usually observed as pustular psoriasis or palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP), and severe acne.1 Far less frequently, hidradenitis suppurativa and other findings of the follicular occlusion syndrome (that is, acne conglobata, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp), and neutrophilic dermatosis, such as ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), Sweet’s syndrome, and Sneddon Wilkinson disease have been reported in association with the syndrome.2 Furthermore, an enteropathic variant with coexistence of inflammatory bowel disease has been recorded.3

Due to the variety of clinical presentations, the treatment of SAPHO syndrome remains a challenge, and results are often disappointing. Recently, there have been encouraging outcomes with the new anti-tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) biological drug infliximab.4

We describe one of the rare hidradenitis suppurativa related SAPHO cases that is additionally remarkable because of its severe clinical presentation including widespread bone disease, a vegetating variant of PG, and collagenous colitis. In our case, infliximab infusions (5 mg/kg) given at weeks 0, 2 and 6 and every 8 weeks thereafter, proved to be only moderately effective.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 43-year-old woman presented with a 3 year history of episodic painful swelling of the left sternoclavicular joint, as well as intermittent watery diarrhoea. She had also suffered from severe axillary hidradenitis suppurativa for 20 years. Despite antibiotic treatment and several surgical interventions in both axillae, pain and discharge had persisted and, moreover, indolent and slowly enlarging vegetating plaques had developed on her thighs 2 years previously; these had been misdiagnosed as inguinal hidradenitis suppurativa.

INVESTIGATIONS

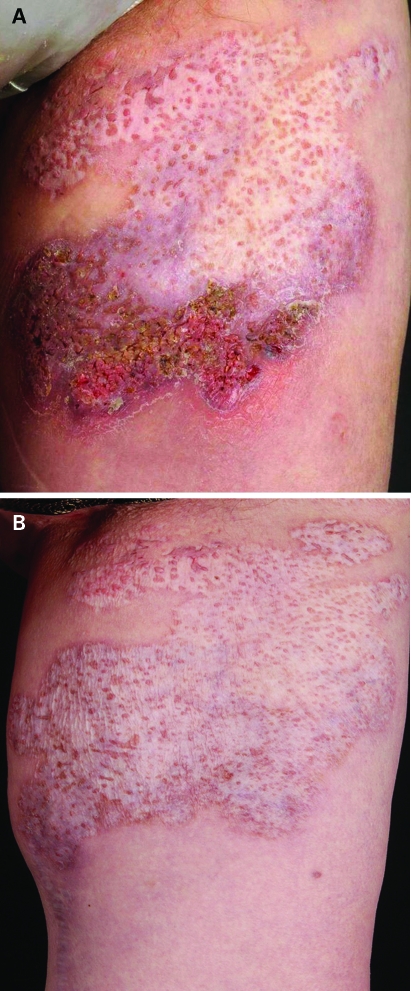

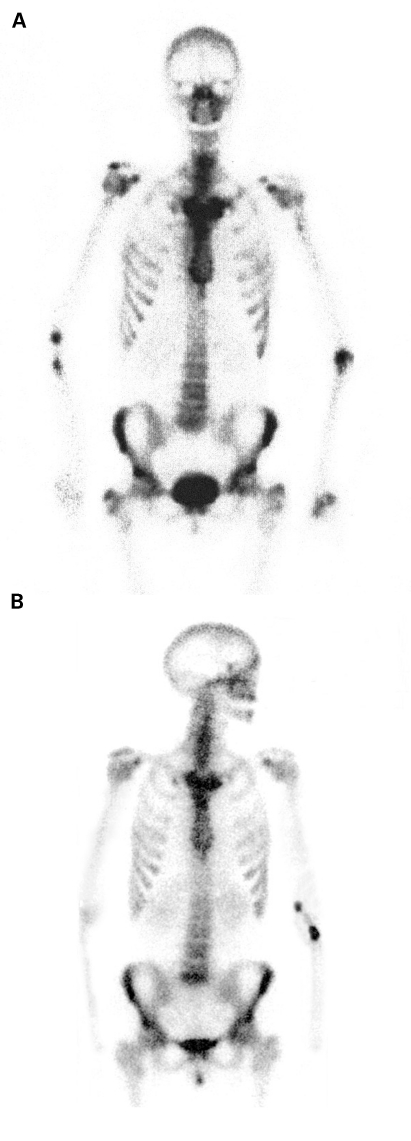

On examination, her left clavicle was swollen, warm and tender, and in the axillary regions, hypertrophic scars, inflamed nodules and draining sinuses were present. Her back, abdomen and thighs showed multiple vegetating plaques, surrounded by extensive depigmented atrophic scars with interspersed hyperpigmented lobate papules and postinflammatory hyperpigmented borders (fig 1A). Histopathologic examination of a skin biopsy of one of these plaques was compatible with a vegetating variant of pyoderma gangrenosum. Quantitative tests for immunoglobulins showed increased serum IgG levels and serum protein electrophoresis revealed polyclonal gammopathy. Complete and differential blood counts and routine blood chemistry were normal, except for C reactive protein (CRP) of 24 mg/l (normal <8mg/l). Results of an additional laboratory workup, including anti-nuclear, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmatic, anti-cardiolipin, and anti-β2-glycoprotein antibodies, cryoglobulins, circulating immunocomplexes, complement factors C3 and C4, lupus anticoagulans, human leucocyte antigen B27 and rheumatoid factor were all normal, as were screenings for viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic diseases. Colonoscopy was clinically normal, but biopsies revealed collagenous colitis. Bone scintigraphy with 99mtechnetium revealed increased radiotracer uptake in the sternoclavicular joints and the manubrium, forming a bullhead sign (fig 2A). Axial T2 weighted magnet resonance imaging showed extensive bone marrow and soft tissue oedema, particularly related to the medial aspects of the left clavicle, as well as inflammatory arthritis of the left sternoclavicular joint, reflecting acute inflammatory involvement.

Figure 1.

(A) Crusted vegetating lesion with flat borders and interspersed fine pustules, surrounded by extensive cribriform scars with postinflammatory hyperpigmented borders on the left thigh. (B) Resolution after the third infusion of infliximab.

Figure 2.

(A) Skeletal scintigraphy showing increased tracer uptake in the sternoclavicular regions, forming a bull’s head sign. (B) New active bone lesions in the right upper jaw and the right sacroiliac joint after 10 months of treatment with infliximab.

TREATMENT

SAPHO syndrome was diagnosed on the basis of all these findings and along with continued treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (diclofenac 150 mg per day), dapsone (50 mg four times daily) was initiated for 18 months, and cholchicine (0.6 mg three times daily) for another 2 months, but without any improvement.

When we decided to start infliximab treatment, the patient had additionally been on oral prednisolone (50 mg once daily, in tapering dosages) for 3 months, followed by cyclosporine A (50mg three times daily) for another 2 months; this had only partially alleviated the chest pain. A noticeable improvement was achieved by intravenous administration of infliximab 5mg/kg given at weeks 0, 2 and 6 and then every 8 weeks, followed by the remission of the vegetating PG (fig 1B) and slight amelioration of the hidradenitis suppurativa. Since the patient refused any combination therapy with other immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate in view of the potential side effects, infliximab was given as monotherapy.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient was free of pain and after the third infusion of infliximab she was able to discontinue NSAIDs. Swelling and tenderness of the left clavicle improved and CRP normalised. After 10 months of treatment with infliximab, she was still free of pain, but scintigraphy again showed increased tracer uptake in the sternoclavicular region, and there were new active lesions in the right upper jaw and the right sacroiliac joint (fig 2B). In the axillary regions, inflamed nodules were still present, and the collagenous colitis was unimproved. During the first 3 months, a few singular red papules developed within the widespread scars, but spontaneously resolved under continued infliximab treatment. Analysis of patient sera taken shortly before the next infliximab infusion revealed low serum concentrations of infliximab (1.5 μg/ml), but drug antibody titres were negative.

DISCUSSION

We report an unusual and severe case of SAPHO syndrome with osteoarthritis, vegetating PG and collagenous colitis, for which infliximab failed to induce persistent disease remission. Although the osteoarticular symptoms and the vegetating skin lesions resolved, the hidradenitis suppurativa improved only transiently, and new active bone lesions were detected by bone scan after 10 months of treatment with infliximab.

To date, 17 cases of SAPHO syndrome and one case of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis treated with infliximab have been reported in the literature.4,5 Fourteen of them presented with bone and skin involvement.

In 16 of the 18 cases,4,5 a persistent remission of osteoarticular symptoms of >21 months was observed after the first or second bolus of infliximab. In the rest, a lack of rapid clinical response after the first bolus guided a switch to pamidronate,6 or loss of efficacy was noticed after the sixth bolus.7

In only nine of the clinically responsive patients, however, did follow-up examinations include imaging techniques, such as bone scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).4,5,7–9 Half of these patients showed new or persistent bone lesions 8–14 months after introduction of infliximab. These findings are consistent with our report, in which active bone lesions were only seen on scintigrams, since the patient was asymptomatic in this respect. MRI examinations appeared to focus only on the clinically affected regions.7 Thus, other sites of bone involvement, as observed in our case, may have been missed.

Cutaneous lesions, especially acne, responded favourably, with a noticeable improvement or remission during the first 3 months of treatment.4 However, PPP sometimes failed to respond4 and recurrences have even been described.9

To date, there has been no report of a hidradenitis suppurativa related SAPHO case treated with infliximab, and further, the present case is the first in which vegetating PG, a non-aggressive variant of PG, was observed in SAPHO syndrome. Outside the context of this illness, infliximab treatment has seemed beneficial for both skin diseases.10 In our patient, only the vegetating PG remitted. This condition is otherwise responsive to simple treatment modes, indicating that skin manifestations are more severe when they occur in the context of this systemic inflammatory condition.

Collagenous colitis represents a very heterogeneous disorder, and may have multiple causes.11 It has occasionally been seen to evolve into inflammatory bowel disease.11 In our patient it may also represent the incipient intestinal manifestation of SAPHO syndrome, which is unresponsive to TNFα blocking agents.12

Review of the literature shows that infliximab has usually been administered at dosages of 5 mg/kg, according to the protocols used in spondylarthropathies, with infusions at weeks 0, 2 and 6 followed by 6 or 8 week intervals.4 Various other regimens have also been employed, including lower dosages of infliximab (3 mg/kg),4,5 and treatment intervals reduced to 4 weeks,8 or adjusted to disease activity.7 Combination therapies with other immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate5,13 or prednisone13 have also been applied. It is remarkable that particularly treatment regimens with lower dosages (3 mg/kg), or decreased infusion intervals as used in spondylarthropathies, failed to induce persistent disease remission.4,5,9 Low dose infliximab in combination with methotrexate was also less effective.5 In four patients with documented infliximab withdrawal,4,9,14 symptoms relapsed 2–6 months after its discontinuation, indicating that 8 week intervals may be too long in some cases. When infliximab was restarted, complaints again resolved almost completely.4,9,14

According to previous research15 and our case, lower infliximab trough values seemed to be associated with a decreased clinical response, suggesting a dose–response relationship. It is unknown whether individual variations in the pharmacokinetics of infliximab, antibody mediated clearance, or simply the complex pathophysiologic mechanisms in SAPHO syndrome influence the therapeutic effect of a TNFα inhibitor. Our patient had no drug antibodies, indicating that other mechanisms might have been involved in the rapid clearance of infliximab.

To enhance treatment efficacy in moderate responders, however, it has been shown that an interval reduction rather than a dose increase might be effective.16 Poor responders tended to benefit from a switch to another TNFα blocking agent.15

We identified an unusual and severe manifestation of SAPHO syndrome with multifaceted and widespread bone and skin lesions, and intestinal involvement in which decreased serum concentrations of infliximab may have been responsible for the only moderate therapeutic effect.

From our experience with the presented case and the scarce information from the literature, we conclude that for moderate responders in particular, appropriate dosages (5 mg/kg) given at shorter intervals than for spondylarthropathies are mandatory to enhance the treatment effect. Based on this schedule, combination therapies with other immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate or prednisone might be useful to minimise the induction of neutralising infliximab antibodies.

As there are no established treatment standards for SAPHO syndrome, we believe that besides the assessment of serum drug values and drug antibodies, repeated bone scans are indicated to verify treatment efficacy.

LEARNING POINTS

SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) syndrome is a severe multifaceted systemic disease.

Bone lesions are progressive and destructive, and usually not clinically apparent at their outset.

Skin manifestations seem to be more severe when they occur in the context of this syndrome.

Intestinal involvement can be masked by its complex clinical presentation.

The anti-TNFα biological drug infliximab can be effective in treating this condition.

In case of moderate responders, more aggressive treatment protocols than previously used are mandatory to induce persistent disease remission.

Measurements of serum infliximab concentrations and drug antibodies, as well as the repeated use of bone scans, may help to define the appropriate treatment regimen for each patient.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Earwaker JW, Cotten A. SAPHO: syndrome or concept? Imaging findings. Skeletal Radiol 2003; 32: 311–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poindexter G, Martinez S, Roubey RA, et al. Synovitis-acne-pustulosis-hyperostosis-osteitis syndrome: a dermatologist’s diagnostic dilemma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59(suppl 1): 53–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schilling F, Märker-Hermann E. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in association with chronic inflammatory bowel disease: entheropathic CRMO. Z Rheumatol 2003; 62: 527–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moll C, Hern·ndez VM, CaÒete JD, et al. Ilium osteitis as the main manifestation of the SAPHO syndrome: response to infliximab therapy and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2008; 37: 299–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asmussen KH. Successful treatment of SAPHO syndrome with infliximab. A case report [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 48(suppl): 621 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amital H, Applbaum YH, Aamar S, et al. SAPHO syndrome treated with pamidronate: an open-label study of 10 patients. Rheumatology 2004; 43: 658–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Widmer M, Weishaupt D, et al. Infliximab in the treatment of SAPHO syndrome: clinical experience and MRI response [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62(suppl 1): 250–1 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deutschmann A, Mache CJ, Bodo K, et al. Successful treatment of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis with tumor necrosis factor-α blockage. Pediatrics 2005; 116: 1231–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massara A, Cavazzini PL, Trotta F. In SAPHO syndrome anti-TNF-α therapy may induce persistent amelioration of osteoarticular complaints, but may exacerbate cutaneous manifestations. Rheumatology 2006; 45: 730–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexis AF, Strober BE. Off-label dermatologic uses of anti-TNF-α therapies. J Cutan Med Surg 2005; 9: 296–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman HJ. Complications of collagenous colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 1643–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulzke JD, Bojarski C, Zeissig S, et al. Disrupted barrier function through epithelial cell apoptosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006; 1072: 288–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iqbal M, Kolodney MS. Acne fulminans with synovitis-acne-pustulosis-hyperostosis-osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome treated with infliximab. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52(suppl 1): 118–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olivieri I, Padula A, Ciancio G, et al. Successful treatment of SAPHO syndrome with infliximab: report of two cases. Ann Rheum Dis 2002; 61: 375–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lutt JR, Deodhar A. Rheumatoid arthritis: strategies in the management of patients showing an inadequate response to TNFalpha antagonists. Drugs 2008; 68: 591–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flendrie M, Creemers MC, van Riel PL. Titration of infliximab treatment in rheumatoid arthritis patients based on response patterns. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007; 46: 146–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]