Abstract

Sleep problems have been reported as an adverse effect of statins. In a randomised trial, simvastatin at 20 mg produced significantly worse sleep quality than either placebo or pravastatin 40 mg. A possible relation to sleep apnoea was hypothesised. Here, the case of a 67-year-old man who experienced sleep apnoea on simvastatin 20 mg is presented. Objective nightly testing showed a prompt, marked, sustained and statistically significant improvement in the obstructive apnoea index when the patient switched to pravastatin 20 mg.

BACKGROUND

Sleep problems on statins, or more specifically lipophilic statins, have been cited in case reports,1–6 adverse event reporting7 and as adverse effects in clinical trials.8–10 Recently a large randomised trial reported significant average reduction in sleep quality with simvastatin (a lipophilic statin) but not pravastatin (a hydrophilic statin) relative to placebo.11 The character of sleep problems on statins has not been elucidated. We present a case of a patient who was diagnosed as having obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) while on simvastatin, whose objective indices of OSA improved promptly and markedly with conversion to pravastatin.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 67-year-old man with a medical history notable for unilateral nephrectomy for renal cell cancer was placed on 20 mg of proprietary simvastatin. Lipid testing conducted 2 months after statin initiation showed a total serum cholesterol of 179 mg/dl and triglycerides of 192 mg/dl (available laboratory printouts do not include high-density lipoprotein (HDL) or low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol). At 20 months, he switched to an equivalent dose (20 mg) of generic simvastatin.

During this time he reported mild symptoms of fatigue and sleepiness and exhibited progression of polycythaemia requiring phlebotomy. Pulmonary sleep testing was performed 5 months after the change in drug (total 26 months on simvastatin). A total of 81 desaturations occurred over a 9 h test period (to less than 89% oxygen saturation) and the patient was diagnosed as having OSA, providing a possible foundation for the polycythaemia. He was placed on bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) (with BiPAP chosen over continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for comfort) employing a data capable flow generator to enable therapy modification (Respironics Auto Bilevel Flow Generator; Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). At 1 month after BiPAP initiation (still on simvastatin 20 mg), total cholesterol was 250 mg/dl, triglycerides 163 mg/dl, HDL 47 mg/dl and LDL 170 mg/dl. At 2 months after initiating BiPAP he switched to pravastatin 20 mg for cost savings.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

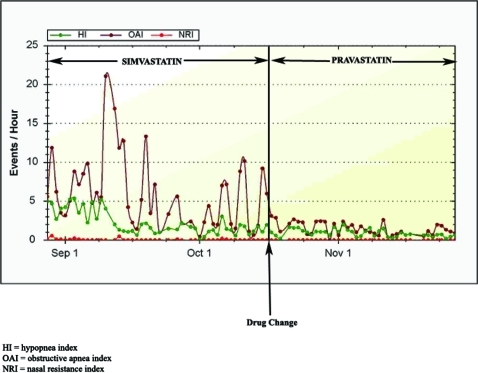

Following the switch to pravastatin there was a prompt and sustained improvement in objective indices on his sleep tracing (fig 1). Mean (SD) obstructive apnoea index (OAI) from nightly recordings over the period before the switch (44 days) was 5.93 (4.53). Mean OAI for the period after the switch (until data were relayed to us, 35 days) was 1.44 (0.86). The difference was highly significant (two-sided t test, p<0.001). There had been no other changes (eg, in weight or alcohol use) to explain the change in OAI.

Figure 1.

Sleep tracing before and after switch from simvastatin to pravastatin. The obstructive apnoea index (OAI) became stably lower following the switch (p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

In the case presented, a patient was diagnosed as having sleep apnoea (associated with polycythaemia requiring phlebotomy) while on simvastatin, and exhibited prompt, marked reductions in objective indices of OSA upon switching to pravastatin at the same dose in mg (but lower expected potency).12

These findings are noteworthy in light of group level data from a recent double-blind randomised controlled trial, the University of California, San Diego Statin Study, in which subjects were assigned to simvastatin 20 mg, pravastatin 40 mg, or placebo. Subjects in the simvastatin arm reported significantly worse sleep quality and significantly greater sleep problems than those either on pravastatin or placebo.11 Trends on pravastatin for “sleep problems” were intermediate between simvastatin and placebo (as was the lipid reduction). However, trends on pravastatin for “sleep quality” were favourable relative to simvastatin and placebo (although non-significant relative to placebo).

Though lipophilic statins have long been speculated to be selectively involved (relative to hydrophilic statins) in reports of sleep complications,13–16 the basis of the putative sleep differences has remained obscure. We have suggested that statin induced changes in mitochondrial function, yielding sleep apnoea, could underlie some sleep problems on statins.17–19 Mitochondrial dysfunction, reportedly a greater problem on simvastatin than on other tested, less lipophilic statins,20,21 has been associated with obstructive18,19 as well as central sleep apnoea.22–24

The findings presented have limitations common to case reports. Effects of a drug in one individual need not reflect average or usual effects. Additionally, it is possible that other factors could be responsible for changes in the sleep tracing unrelated to, but coincident with, change of treatment to pravastatin. CPAP/BiPAP itself can improve upper airway patency25 but would not be expected to be responsible for a later abrupt change in the OAI, coincident with the statin drug change. The marked magnitude, the sustained character of the change, the tight temporal association in the sleep tracing with the change in drug from simvastatin to pravastatin, the fit with randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence based on group level data regarding sleep on simvastatin relative to pravastatin and the consistency of the putative effect with known physiology and previously articulated hypotheses provide evidence favouring a causal connection between the change in sleep tracing associated with the change in drug.

To our knowledge this case provides the first evidence to suggest that pravastatin relative to simvastatin (and/or lower potency relative to higher potency statins) may influence sleep apnoea spectrum conditions. Future studies, such as double-blind placebo-controlled crossover studies, might be conducted in patients who report statin-associated sleep problems. This may help to better characterise the more general association of statin agent and/ or dose to pulmonary sleep disorders in patients citing sleep problems on statins.

LEARNING POINTS

Sleep problems occurring on statins may in some cases relate to sleep apnoea.

Simvastatin has previously been reported to cause sleep problems more commonly than pravastatin.

A switch to pravastatin may benefit some patients who develop sleep problems on simvastatin.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tobert JA. Lovastatin-associated sleep and mood disturbances. Am J Med 1995; 99: 108–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boriani G, Biffi M, Strocchi E, et al. Nightmares and sleep disturbances with simvastatin and metoprolol. Ann Pharmacother 2001; 35: 1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allain P, Cailleux A. Insomnia, lovastatin and isoprene [in French]. Therapie 1990; 45: 47–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenson RS, Goranson NL. Lovastatin-associated sleep and mood disturbances. Am J Med 1993; 95: 548–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinzinger H, Mayr F, Schmid P, et al. Sleep disturbance and appetite loss after lovastatin. Lancet 1994; 343: 973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black DM, Lamkin G, Olivera EH, et al. Sleep disturbance and HMG CoA reductase inhibitors. JAMA 1990; 264: 1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buajordet I, Madsen S, Olsen H. Statins - the pattern of adverse effects with emphasis on mental reactions. Data from a national and an international database [in Norwegian]. Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening 1997; 117: 3210–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malini PL, Ambrosioni E, De Divitiis O, et al. Simvastatin versus pravastatin: efficacy and tolerability in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia. Clin Ther 1991; 13: 500–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung N, Cho SY, Choi DH, et al. STATT: a titrate-to-goal study of simvastatin in Asian patients with coronary heart disease. Simvastatin Treats Asians to Target. Clin Ther 2001; 23: 858–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lovastatin Study Groups I–IV Lovastatin 5-year safety and efficacy study. Arch Intern Med 1993; 153: 1079–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golomb BA, Kwon EK, Criqui MH, et al. Simvastatin but not pravastatin affects sleep: findings from the UCSD Statin Study. Circulation 2007; 116(Suppl II): 847 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts WC. The rule of 5 and the rule of 7 in lipid-lowering by statin drugs. Am J Cardiol 1997; 80: 106–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Illingworth DR, Tobert JA. A review of clinical trials comparing HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Clin Ther 1994; 16: 366–85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kostis JB, Rosen RC, Wilson AC. Central nervous system effects of HMG CoA reductase inhibitors: lovastatin and pravastatin on sleep and cognitive performance in patients with hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Pharmacol 1994; 34: 989–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roth T, Richardson GR, Sullivan JP, et al. Comparative effects of pravastatin and lovastatin on nighttime sleep and daytime performance. Clin Cardiol 1992; 15: 426–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vgontzas AN, Kales A, Bixler EO, et al. Effects of lovastatin and pravastatin on sleep efficiency and sleep stages. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1991; 50: 730–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golomb BA, Evans MA. Statin adverse effects: a review of the literature and evidence for a mitochondrial mechanism. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2008; 8: 373–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sembrano E, Barthlen GM, Wallace S, et al. Polysomnographic findings in a patient with the mitochondrial encephalomyopathy NARP. Neurology 1997; 49: 1714–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeyakumar A, Williamson ME, Brickman TM, et al. Otolaryngologic manifestations of mitochondrial cytopathies. Am J Otolaryngol 2009; 30: 162–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schick BA, Laaksonen R, Frohlich JJ, et al. Decreased skeletal muscle mitochondrial DNA in patients treated with high-dose simvastatin. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007, 81: 650–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velho JA, Okanobo H, Degasperi GR, et al. Statins induce calcium-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition. Toxicology 2006; 219: 124–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakaue S, Ohmuro J, Mishina T, et al. A case of diabetes, deafness, cardiomyopathy, and central sleep apnea: novel mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms. Tohoku J Exp Med 2002; 196: 203–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tatsumi C, Takahashi M, Yorifuji S, et al. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, ataxia, and sleep apnea. Neurology 1987; 37: 1429–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tatsumi C, Takahashi M, Yorifuji S, et al. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with sleep apnea. Eur Neurol 1988; 28: 64–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corda L, Redolfi S, Montemurro LT, et al. Short- and long-term effects of CPAP on upper airway anatomy and collapsibility in OSAH. Sleep Breath 2009; 13: 187–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]